Milton Guran* has the mellow look of someone who has lived through a lot. As an anthropologist and photographer, he has devoted his life and career since 1978 to documenting the Indigenous peoples of Brazil and portraying identity issues in West Africa. From 1986 to 1989, Guran was a photographer for Brazil’s Indigenous Museum (Museu do Índio), and in 1987 he registered the first contacts of “white people” (non-indigenous people) with the Arara of Cachoeira Seca, on the banks of the Iriri River in Pará state. Thirty-one years later, the anthropologist and photographer returned to the Amazon, fearful of the brutal impact the government of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) might have on Indigenous peoples—a concern that proved to be justified in the following years.

It is this precious material, gathered at two points in time and most of it still unpublished, that Milton Guran now offers SUMAÚMA readers. The historical power and beauty of the images are complemented by observations from his field diary, where he recounts in great detail this unique experience of first contact with a people who wish they had never been touched by whites. Three decades later, Guran shares his sadness upon discovering that the soul of a people has been destroyed.

In his apartment in Rio de Janeiro, where large windows bathe his high-ceiling living room in soft light, every shelf is crowded with books and documents. On the walls, extraordinary photographs tell life stories, Milton’s included. Before our SUMAÚMA team takes his picture, he offers us a cup of coffee. Then he vanishes to change his shirt, but not his flip-flops. When he returns to the room a few minutes later, he is carrying an overflowing cardboard box. Out of it comes a treasure trove, a small notebook, every single, discolored page filled—it is his field diary as an anthropologist, where he recorded what he saw and felt on the Iriri River in Terra do Meio, or Middle Earth. Photographs printed on sulphite paper are scattered across the table in front of him as Milton Guran explains how he captured the lightness of the Arara at a time when they lived in complete harmony with nature and then, years later, how he perceived the disastrous effect of interventions in their Indigenous culture.

Today, the Arara of Cachoeira Seca are still waiting for the government to expel the invaders from their lands, a promise that has been continually postponed. The Arara are suffering threats and violence, endangered especially by heavy traffic on the Trans-Iriri, a road that land grabbers and illegal loggers use to transport spoils from the rainforest to the Trans-Amazonian highway—a road that began their demise and has never stopped stealing their lives since.

(Lela Beltrão, photo editor, and Malu Delgado, news editor)

Milton’s eyes: the photographer and anthropologist in his home in Rio de Janeiro, his field notebook, and the photographs. Photos: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

Altamira, Iriri River, Terra do Meio

In 1987, I was working as a photographer at the Indigenous Museum in Rio de Janeiro [now the National Museum of Indigenous Peoples], where my main job was to systematically document various Indigenous peoples in Brazil. Naturally, given their obvious importance, we had a special focus on isolated peoples.

In the 1970s, when [the government] opened BR-230—theTrans-Amazonian highway— there were fierce clashes between Indigenous communities and the workers building the road. They called in the department responsible for isolated peoples within Brazil’s Indigenous agency Funai, then headed by Indigenous affairs expert Sydney Possuelo. [The agents] identified the people as members of the Arara, an ethnic group thought extinct since the early 20th century. The work of attracting the Arara to Funai posts and getting them to engage with us was a very bumpy road, including an incident in which Afonso Alves da Cruz, Amazon specialist, took an arrow to his chest. But by 1980, firm contact had been established.

After contact was made with the main group, only a small number of isolated Indigenous people continued to roam the forest between the Trans-Amazonian highway and Iriri River, a tributary of the Xingu. This group—now known as the Arara of Cachoeira Seca but who call themselves Ugoro’gmo—were the victims of systematic persecution by land grabbers, hide hunters, and loggers. Numerous clashes occurred, with several deaths, until finally the Indigenous agency Funai, under Possuelo’s leadership, managed to isolate the area where the isolated people were wandering and do the work of drawing them to the post, a task completed in October 1987.

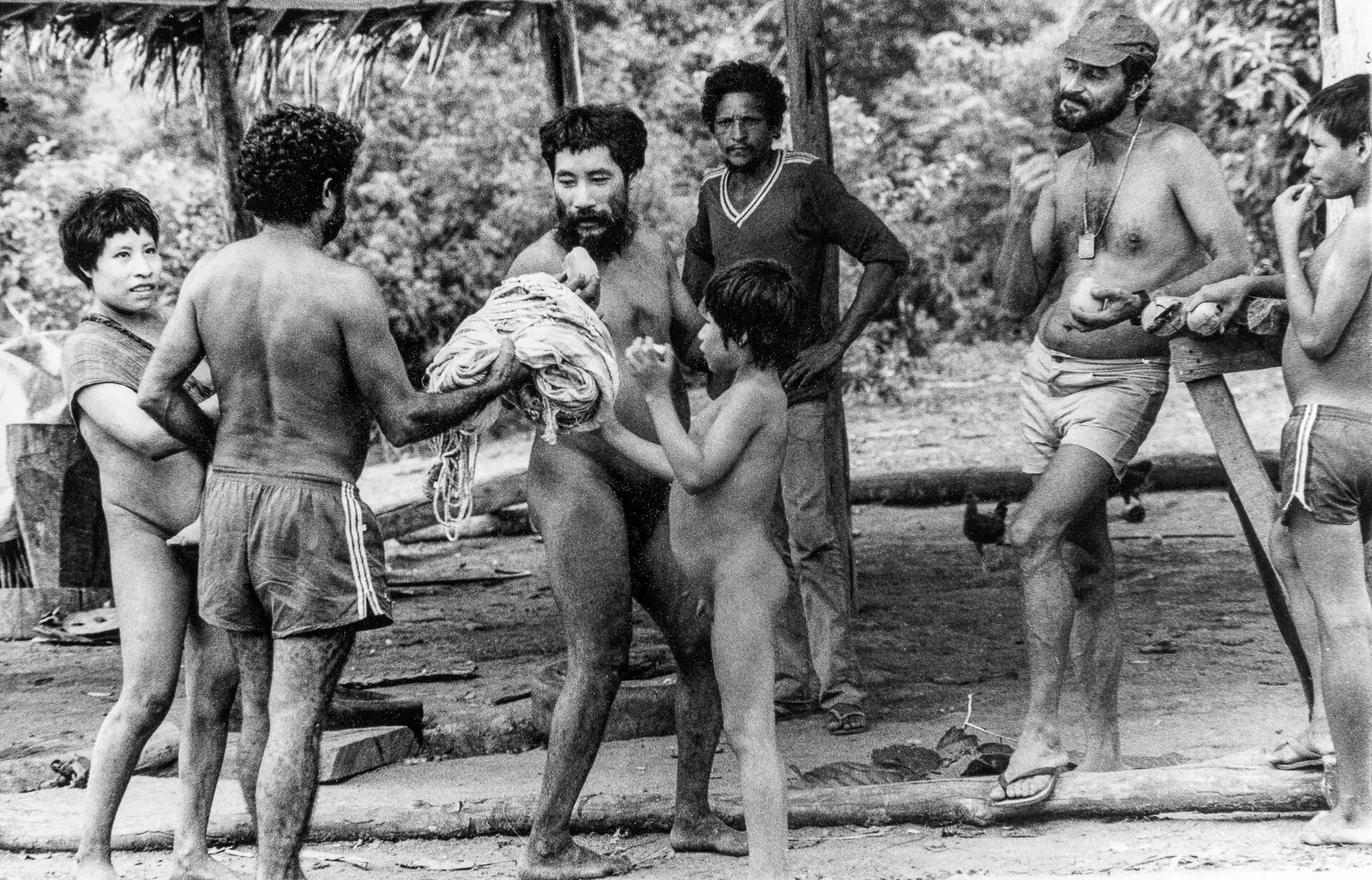

From left to right: Elepó (Tibie’s wife), Afonso Alves (head of the “attraction post,” wearing shorts), Tibie, Tybyrybi (boy), Manuel Evangelista Brito da Silva (nurse, wearing a shirt), Sydney Possuelo (with a cap), and Tiuvandem

At the Indigenous Museum, we closely followed the work of the

so-called Arara Attraction Front, which had succeeded in convincing the government to block off the territory where this group of isolated people was roaming. Headed by the Indigenous affairs specialist Afonso Alves da Cruz [a central figure in the defense of Indigenous peoples in Brazil, especially isolated groups], a surveillance post was set up on the banks of the Iriri River, on the main road into the territory. Another attraction post, called Liberade—Freedom—was established some 28 miles from the river, deep in the forest; gifts were regularly put out for the isolated peoples, who almost never let themselves be seen. Until one day a few men suddenly showed up at the post and told us they would return after a while.

At that time, we were always trying to get the latest news on the

Attraction Front. One day when I was in Brasilia for personal reasons, I went to Funai to ask about it and learned that Sydney had gone to Altamira, because the isolated people were about to visit the Funai post. With authorization from the museum, I left for Altamira, taking along only the basic photographic equipment I had with me at the time.

We waited three days for the isolated people to appear at the Iriri River post. Headed by Afonso Alves da Cruz, the staff there consisted of eight Amazon specialists, including two nurses, all of them very experienced in this type of work. Since they were almost certain the isolated group was in fact Arara, Sidney Possuelo added two young men to the team, Aktô, who was around 16, and Tiuvandem, a little younger, both from a separate Arara group contacted in 1980.

The isolated people finally showed up, led from their camp deep in the woods by Aktô. I watched the group’s arrival through a hole I had opened in the wall of a makeshift building at the post, just big enough to fit my telephoto lens through.

This is how I recorded the event in my field notes:

Lapi and Tatimm with Wiló in her arms

1987

Oct. 7th, Wednesday, Iriri (Cachoeira Seca Attraction Post)

The isolated people arrived a little before nine o’clock in the morning, in a group, entering the post with the sun in their faces. There were 28 of them in all, 11 adults and 17 children, two still young enough to be carried. The adults each balanced a mat of woven babassu palm fronds on their heads; they were in good spirits, chatting, everyone talking at once. Sydney decided to leave the video camera on the table. Most of the men went to wait for him under a thatched roof where there were bananas set aside for them. They began engaging with us immediately.

When Aktô said he was Arara (they call themselves the same name) from the other side of the hills, one of them said he knew Piput, one of the eldest and most respected Arara, and Aktô’s father. There was much celebration. The isolated people also remembered Wapuri. It might have been a coincidence the names were the same, but Sydney believes they really were the Arara contacted in 1980. According to him, the break in contact between the groups of Arara began in 1970 with the Trans-Amazonian highway […].

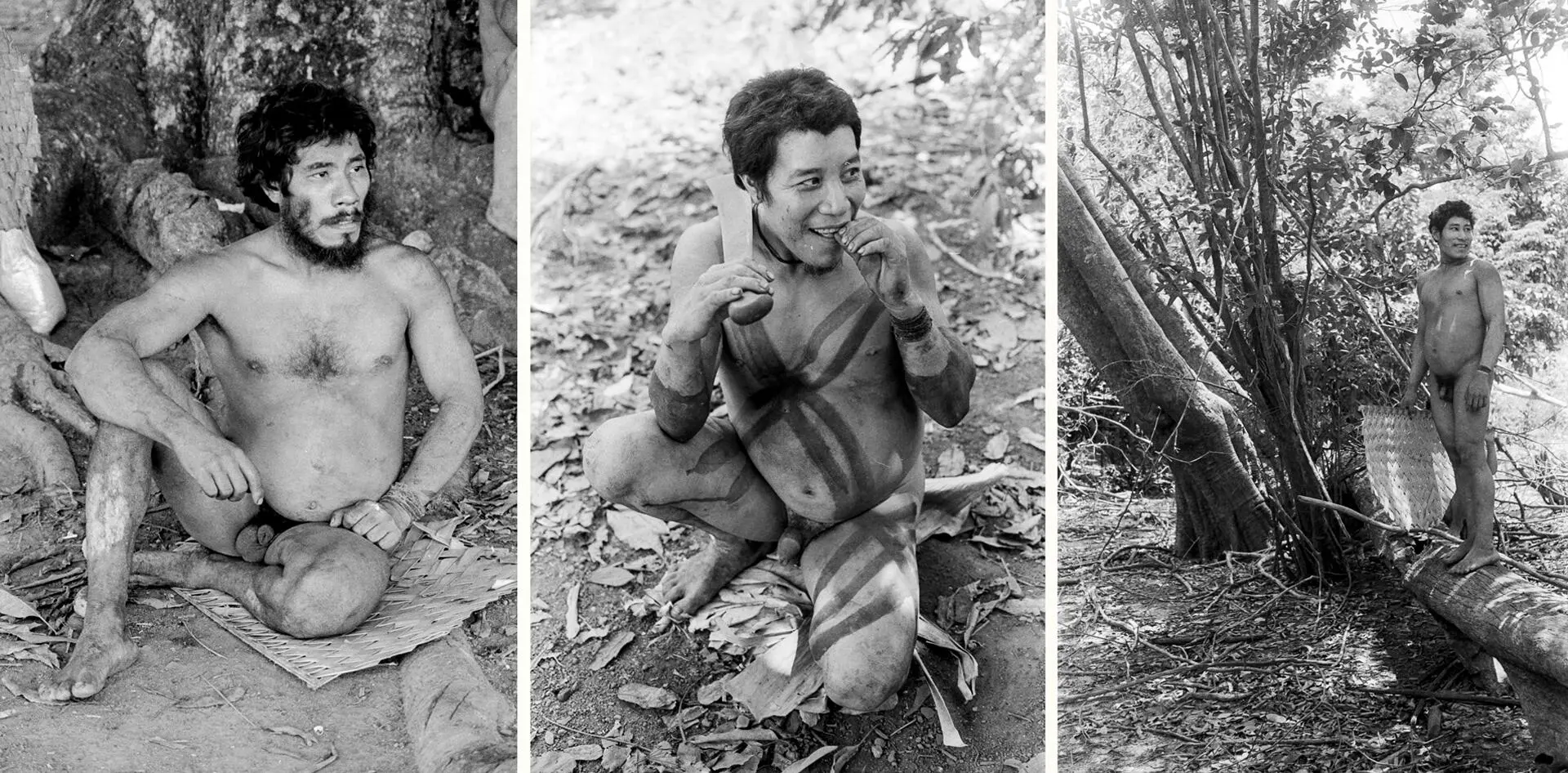

From left to right: Gugu, Puy, and Tchagat

The men are around 5’ 2’’ tall. They’re bearded, potbellied, and not particularly strong. They seem to be healthy, have all of their teeth, smooth skin, no lesions. Some show traces of black genipap paint. These are X-shaped lines on their chests and thighs. The men wear a cord around their necks with a monkey bone dangling down their backs. Others have a cord tied around their wrists. Children are held on the left side [of their mothers’ bodies] by straps made of fibers or cotton.

From my hiding spot behind the kitchen wall, I only managed to take a few photos of the group’s arrival before one of the men, apparently the chief, stared right into the center of my lens. Although he was over 20 yards away and I was in the shadows, he had noticed that something was off. When he glanced away for a moment, I removed the camera and covered the hole. I crawled carefully away. When I joined the rest, I aroused more curiosity than I would have liked. I was wearing shorts and sandals, like everyone else.

They stared at me and talked a lot. Sydney and I are newcomers [to the group], and they don’t know us yet. They spoke loudly, some surrounding me. They gradually moved away. A few returned. A woman with a child at her breast kept staring into my eyes. I smiled; she smiled back. I held out my hand, she took my fingers and called the others over. She kept talking to them while swinging my hand […].

The visit from the isolated people only lasted two days. When they said they were leaving the next day, I decided to bring out the camera. They ran away from it, exclaiming things.

Through the interpreter Tiuvandem [Aktô’s cousin, about 14 years old, who Sydney brought to help with translation and social interactions], I discovered they thought it was a weapon. I explained it wasn’t a weapon and asked Tiuvandem to take my picture. But he had never touched a camera before, so he just fumbled with it and the Arara scattered in all directions. Drawn by the confusion, Aktô came and let himself be photographed, calming everyone down.

I pointed the lens at my own face and gestured to the chief to look through the viewfinder. When he approached the viewfinder, I snapped the shutter. He leapt back, but laughed. Then I turned the lens toward him and took the first portrait photograph.

From then on, even though many of them didn’t feel comfortable with the presence of the camera, I was able to discreetly take around 300 black-and-white photos and a few color slides. The next year, a selection of these photos was shown in the Indigenous Museum in Rio de Janeiro with the title: “Wokarangma – The Isolated People of the Iriri River.”

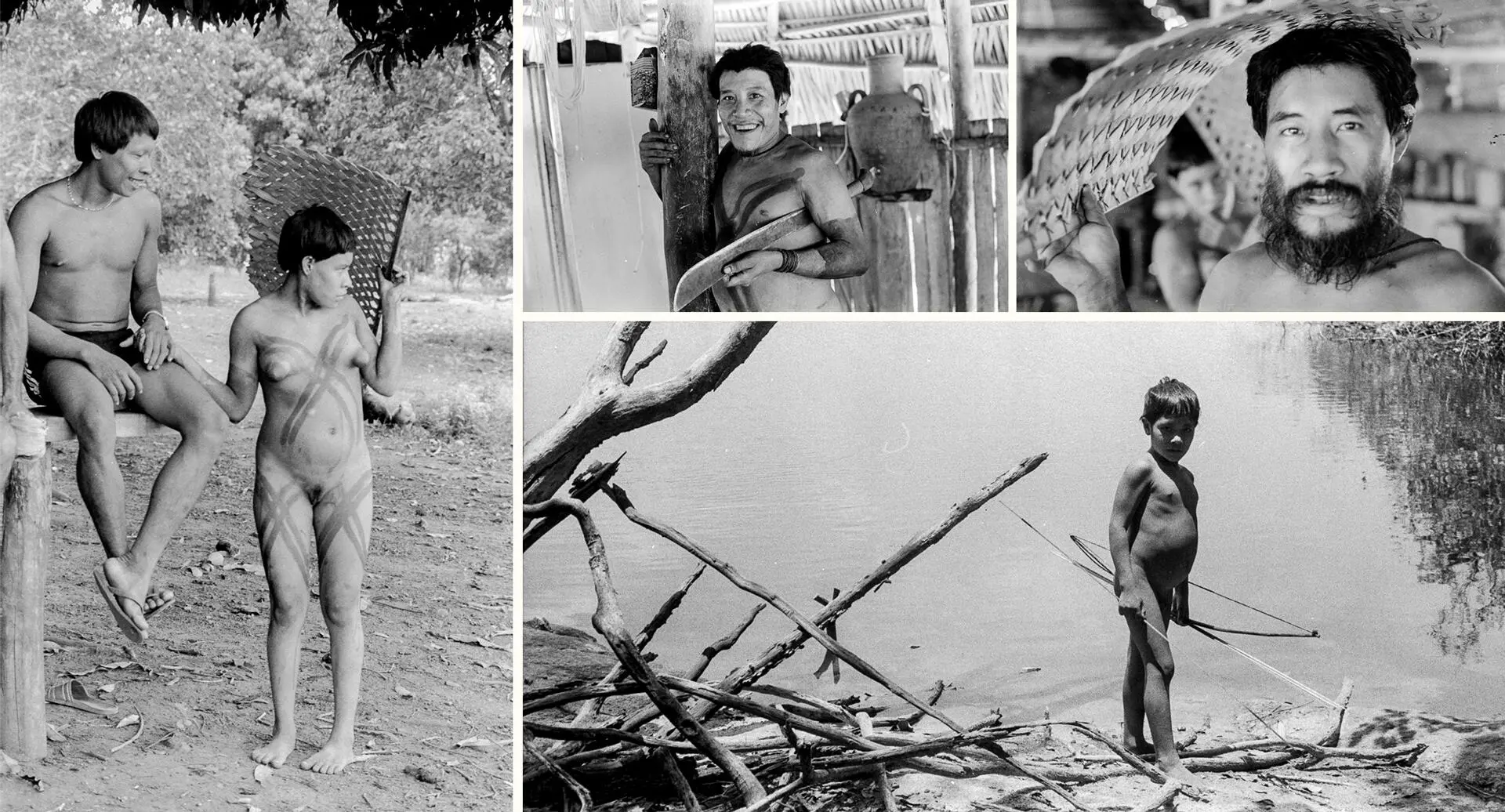

Aktô and Poty (left). Puy, Tibie, and Idomeduk (with bow and arrow)

After three decades of contact…

2018

Demarcation and ratification of the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory came in 2016 as part of the environmental licensing requirements for construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant complex. But through a series of subterfuges, the traditional Arara lands were split into two separate sections with no communication between them: Arara Indigenous Territory (also known as Laranjal), where most of the Arara people contacted in 1980 now live, and Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory, home to the group contacted in 1987.

Protection of these demarcated areas and the eviction of non-Indigenous invaders fell to the Belo Monte plant, which was required to implement compensation policies. In Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory, a visitor to the village quickly sees that these policies don’t truly seek to protect or preserve Indigenous culture as they should. On the contrary, they deliberately wear away at the cultural foundations of the Arara, leaving them dependent on Brazilian society and particularly on Norte Energia, the company that manages the Belo Monte hydroplant.

This aberrant state of affairs traces back to 2007, when Funai decided to remove heads of agency posts from Indigenous areas, where they had been acting as intermediaries between the Indigenous peoples and Brazilian society. The Arara of Cachoeira Seca, who are considered recently contacted and therefore less equipped to understand how our society works, are among those left most defenseless.

The territory of Cachoeira Seca was the most invaded and deforested area of the Amazon in 2018. On December 30 of that year, according to reports by the Indigenous people, a large number of heavily armed land grabbers invaded Arara lands, driving in from the Trans-Amazonian highway on tractors and immediately commencing deforestation of the area. Funai tried to intervene, and Federal Police teams were also sent in but, as usual, the impasse continues. Since then, the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory has remained one of the most devastated areas of the Amazon.

In December 2018, or 31 years after the initial contact registered in our documentation, I was finally able to return to the area and show the Arara their first photographic images.

With the support of the Indigenous Museum of Rio de Janeiro and an independent film production company, I traveled there with Thiago da Costa Oliveira, an anthropologist specialized in video documentation. The idea was to identify empirical elements to be used in assessing how contact has impacted the group. I tried to record relevant aspects of their lives over this period of time—demographics, life stories, cultural transformations, and so on.

One of the central concerns of this research was to understand the different ways in which non-Indigenous people have been perceived over time, from before first contact to the present. And this includes key moments, like the steady interactions with Funai post staff that marked the early years of Arara relations with the non-Indigenous world. For this purpose, we used a dialogical methodology based primarily on the images produced when the group first had contact with the Funai team. We relied on photographic records as a starting point for an experimental encounter involving ethnographic and narrative sharing, through both informal interviews and other interviews recorded by video.

The situation we found when we arrived at the village was extremely bleak. Their traditional lodgings had been replaced by wooden houses built by Norte Energia, the consortium that owns the concession for Belo Monte. The houses were much like those built by settlers from southern Brazil, standing in a circle with porches facing the backs of their neighbors’ homes—not the traditional layout of Arara villages.

Typu (in the green dress) and Tibie (right)

The whole area was inundated with industrial waste. Though we could see everyone had made a valiant effort to defend their language and what remained of their traditional culture, it seemed they were fighting an inglorious battle in the face of disproportional pressure from the society surrounding them.

The photos, printed in A4 format, stirred great curiosity, as to be expected. The more elderly didn’t immediately recognize themselves in the photos, since at the time the pictures were taken, they hadn’t known what they looked like. Someone had to tell them “this one here is really you” for them to believe their eyes.

Those who were children 30 years earlier recognized themselves easily because they had been photographed with their parents or siblings. But what struck us the most was that today’s teenagers were astonished when they saw that their elders had walked around naked. The young people’s surprise is testimony to their complete ignorance of their historical and social heritage and definitively certifies a process of advanced ethnocide [cultural death]. It was based on this observation that we carried out our research, including photographic and video documentation of the facilities and daily life in the village.

The 30 years of contact are imprinted on the faces of the older people, those who have long lived in the transition between traditional ways of life and the way of life resulting from the negligence of Brazilian society. The portrait of the disaster is intertwined with the portrait of its victims. The story of this group of Arara is a saga of constant struggle and unshakeable resilience. This has been the case since the group split from the main village, perhaps some 70 years ago, and continues to be the case in the battle with the powerful Belo Monte hydroelectric plant and the prejudiced, violent city Altamira.

Puy and Tchagat holding photos of themselves taken in 1987, before the arrival of Belo Monte

These people are currently gaining a growing awareness of their rights and the value of their culture, joining forces with their Indigenous neighbors and with Ribeirinhos, members of traditional forest communities, in the fight to defend their values and lands.

In 2019-2020, through a study sponsored jointly by the Indigenous Museum and UNESCO, we took our research a step further by including Arara youth, who participated in a photography and oral history workshop offered in partnership with Professor Ana Maria Mauad, of the Oral History and Image Laboratory at Fluminense Federal University. The young people’s initial surprise gave way to an awareness of the importance of their own history. This two-stage, in-person workshop was attended by six young men and six young women at the Cachoeira Seca village. During the first stage they were introduced to photography and interview techniques. Then we collected all of the material and analyzed it before returning for the second stage.

The original images triggered a whole host of ideas, suggested new pathways, and enriched the research. The people photographed in 1987 weren’t familiar with photography or even with mirrors, which means that, as individuals, they didn’t know their own image at the time it was taken. Judging by their amazement at seeing their elders naked, the second generation of Arara, who grew up after contact with Funai, hadn’t been aware they were experiencing the radical erasure of their traditional culture.

When I gave them back their photos, the group was basically confronted with their own history, their own culture. Never before had I felt, in such a powerful, gratifying way, that 30-year-old photographic documentation could play a lead role in the reconstruction of a group’s narrative about themselves and their recent history.

The workshop prompted a re-remembering of history. The twelve young participants shared six cameras and six digital recorders provided by the project. Armed with and informed by the photos from 1987, they did their own research, asking their elders questions. One of them was me, the only non-Indigenous eyewitness available.

Milton Guran (in white shirt) being interviewed by participants of the photography and oral history workshop. Photo: Okré Arara

When I gave the photos to the community gathered in the House of Culture [the space in the village where they hold collective meetings], I had already delivered a public report on what I had witnessed, but during this interview, they questioned me intensely about a wide range of aspects of the situation and displayed keen interest in that refoundational moment in the group’s history. At the end of the interview, 16-year-old Pugyromã, who appears in a red shirt on the right in the photo, was quick to say they hadn’t known anything about this, and it was important to know. Her statement sparked a lively discussion among the participants.

For the Arara of Cachoeira Seca, giving them back their photos meant “giving them back” their own history.

Iogó, in 1987 and 2018

* Milton Guran was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1948. He holds a doctorate in anthropology from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, in Marseille, France (1996), and did post-doctorate work at the University of São Paulo (USP). He has a master’s degree in social communication from the University of Brasilia (1991). He worked as a photojournalist from 1975 to 1992 and also served as professor at the University of Brasilia and at Gama Filho University and Cândido Mendes University, both in Rio de Janeiro. Since 2006, he has been a researcher with the Oral History and Image Laboratory at Fluminense Federal University in Rio de Janeiro.

Report and text: Milton Guran

Editing: Malu Delgado e Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Maria Jacqueline Evans and Diane Whitty

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum