“While society is made up of equals, the community is made up of the diverse. We are the diverse—cosmological, natural, organic. […] We are all cosmos, except for humans. I’m not human, I’m a Quilombola [descendent of enslaved African rebels]. I’m a farmer, a fisher, a being of the cosmos.”

From the book A Terra Dá, a Terra Quer, by Brazilian writer and intellectual Antônio Bispo dos Santos (Nego Bispo)

When it storms in the community of Jocojó, 88-year-old Gabriel Soares da Conceição relives the terrifying night he spent between heaven and hell. He was coming back from fishing on the Jocojó, a coffee-colored river that leads to Gabriel’s community and lends it its name, when the downpour hit. He decided to take a shower in the rainwater streaming off the roof gutters. As he stretched out his cupped hand to catch some water to bless himself, he heard the boom—and was struck by lightning. “I could only say ‘Our Father’. Couldn’t get to ‘the Son’ or ‘Holy Ghost’. I fell down.” The electrical discharge left burns on his body and knocked him out for several minutes.

While Gabriel lay there unconscious, he says he was transported to hell, where he has a clear memory of being offered a plate of food. “I hadn’t eaten a bite till then,” he says. But the meal caught fire before he could taste it. Then he departed hell and was soon at heaven’s doors—but he didn’t make it through them. A messenger at the gates said he should be sent back: “It’s not his time yet.”

Gabriel survived but he’s never been the same. He takes comfort in the saints, although he finds himself shaking whenever “weather starts brewing” in Jocojó.

Gabriel Soares da Conceição, the oldest folião, or celebrant, in Jocojó, keeps a living shrine of memories on the wall of his house. Photo: Soll/Infoamazonia and SUMAÚMA

Nor has the weather in Jocojó ever been the same, something Gabriel knows full well. The climate is growing increasingly unpredictable and perplexing in the municipality of Gurupá, located in the Marajó Archipelago, in the Lower Amazon region, in Pará state. Old-timers know everything is different here now. Hotter. Rainier. Dry like never before. Gurupá encompasses 12 quilombo communities, originally founded by enslaved African rebels. Scattered across 83,000 hectares of titled land, they are home to 740 families.

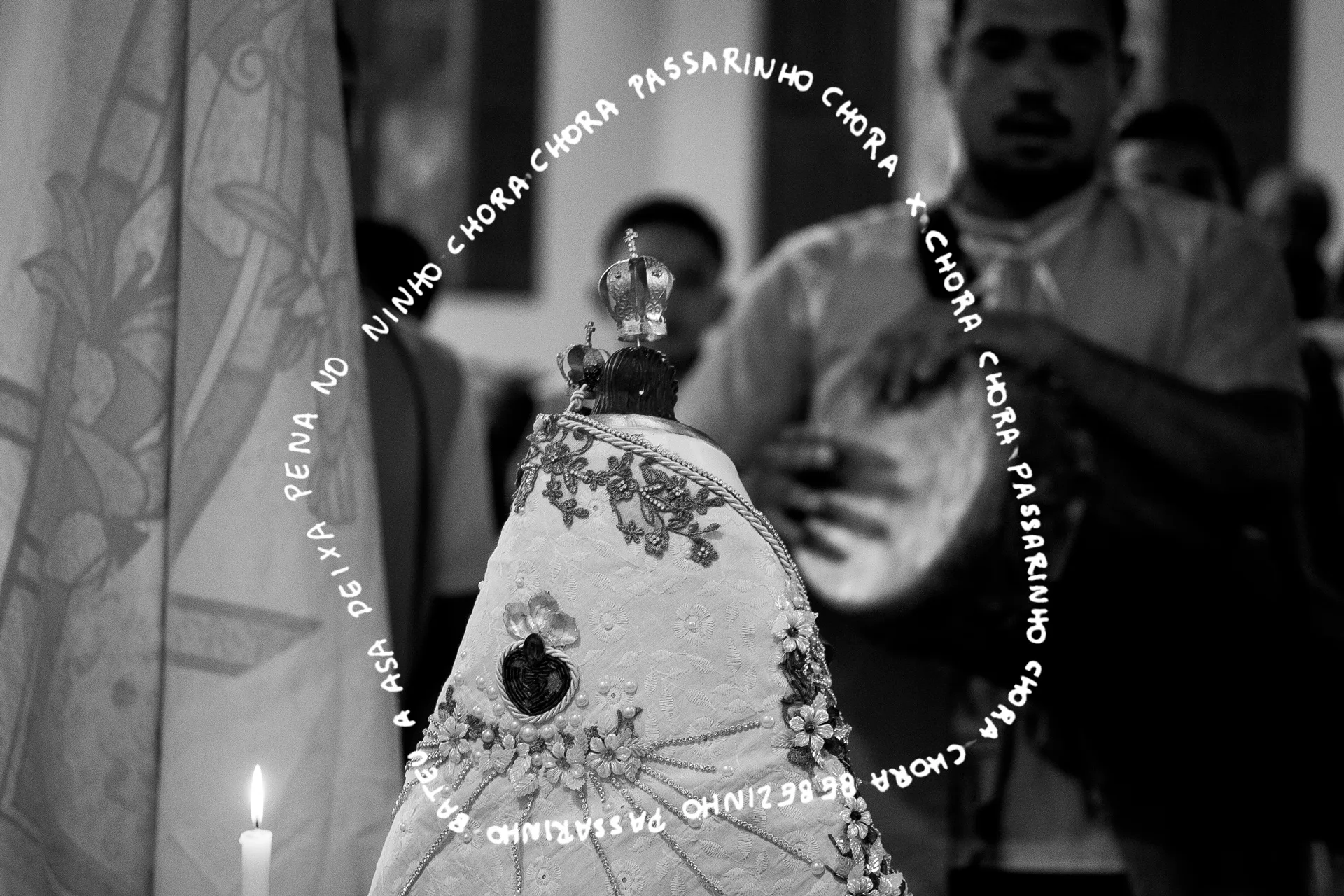

The quilombos of Gurupá are a land of devotions, apparitions, and enchanted beings, and homes filled with saints, where faith and imagination in all their diversity converge with the forest itself. A gamut of religious practices find expression here, from faith in protective spirits of the rivers and forest to the sound of Afro-Brazilian drums echoing through the temples during the celebrations known as folia. There is a deep bond with bodies of water, and rivers become paths for the floating processions known as half-moons.

But Gurupá, like the entire Amazon, is suffering the effects of extreme weather events. Devotees, rezadeiras (faith healers), and foliões (celebrants) belonging to time-honored lay associations known as irmandades, or fellowships, must confront heat, drought, and storms. They are forced to find new ways of practicing their traditions.

Ivanete Duarte Fernandes feels it in her bones. The 41-year-old school cook lives at the end of the main street in Jocojó Quilombo, a dirt road where you won’t find a soul outside when the sun is at its peak. It’s hard to take the heat even indoors, under roofs made of Brasilit tiles, a composite of cement and synthetic fiber. The only thing that refreshes Ivanete is her recollection of the esmola religious processions she took part in as a teen. During these collective manifestations of faith and solidarity, the foliões from the fellowships visit the homes of the community’s devotees carrying images of saints. As they go from house to house, the foliões pray, socialize, sing, and collect donations for the auctions held during the festivals.

Her image of Our Lady of Sorrow is protected by a sheet of plastic, a sign of Etelvina’s care and devotion to the saint, who gives her hope for better days. Photo: Soll/Infoamazonia a SUMAÚMA

Conversion and resistance where forms of faith meet

Gurupá has always been a crossroad of rivers, where faith flows into an array of channels and religious traditions interweave. Before the colonizers arrived in their galleons and caravels, the region had been both a meeting point and a hub for Moitarás, that is, the exchange of artifacts between Indigenous peoples, who traveled the waters in canoes and other small vessels carved from the trunks of single trees, conveying people, offerings, and spiritual knowledge. In a cosmovision shared by many groups, Earth, lowland rivers, and more-than-human kin are considered beings who possess personalities and spirits and deserve as much respect as human people.

From the Iberian peninsula came Catholic doctrine and, through the work of Jesuit missions, the Christian faith was imposed on Indigenous peoples even before the founding of Gurupá, in 1623. The Portuguese Crown first established a military outpost here and then built Santo Antônio Fort at the top of the riverbank where the municipality is now located. It was on these banks that African faith traditions and knowledge were brought ashore along with the enslaved Blacks abducted to the Amazon. For many colonizers, including Jesuits and other missionaries, Indigenous peoples and enslaved Africans had no souls in the Christian sense, and their religiosity was seen as inferior, justifying the “need” to convert everyone to Christianity.

Conversion was by force. The Black and Indigenous peoples of Gurupá held firm to their faith as best they could, discovering ways for their traditions to coexist with new ones and seep out through the cracks. For Robson Lopes—a scientist of religion and historian who has been researching Popular Catholicism and the lay associations of Gurupá for years—the pretos velhos who are members of the Fellowship of the Celebrants of São Benedito of Gurupá are like “a religion within a religion.” “They follow the doctrine of Lusitanian Catholicism, brought by the Portuguese Crown. But they use the religious code of Catholicism to express their own codes, found in fragments of memory, symbols, gestures, and canticles, which do not take the form of doctrine,” says Robson.

Fire and heat force schedules to change

The day of the esmola procession is one of the most important in the year for José Edir Nascimento Pantoja, 75, folião with the fellowships of São Benedito, Our Lady of Nazaré, and several others. At gatherings of lay associations in Gurupá, he learned how to play the instruments used in these celebrations from his grandfather and from 80-year-old Francisco Pereira Santana, the mestre-sala, or leader, of the foliões. Edir began by mastering the xeque-xeque, also known as a milheiro, a shaker made from a piece of hollow trunk. He then moved on to the drums, like the tamborinho and tambor maior. The latter is sometimes played by two percussionists, one thumping the head as he straddles the long drum beneath him, the other striking the lower end of the barrel with sticks. His whole day would be spent in revelry. Families gave the saints and foliões heartfelt receptions, their tables decorated for the occasion and ladened with cakes, coffee, soft drinks, mush—whatever the devotees could offer from their heart. This human warmth and the musical festivities have stood the test of time but not of the blazing heat, which now keeps the foliões from celebrating all day long.

The mouth of the Gurupá Mirim River is a gateway to the homes on stilts where locals reside. Folião José Edir and his family live here among birds and Açai trees. Photo: Soll/Infoamazonia SUMAÚMA

In the past, devotees would stay out until the evening, after they had visited all the homes. “Now, for God’s sake, it’s too ridiculously hot,” complains Ivanete Duarte. There hasn’t been a good rain for over two months, and summer isn’t even at its hottest. Things are much the same in Gurupá Mirim, a nearby quilombo. In late September, Edir made plans for his round of visits during this year’s festival of Our Lady of Nazaré, patroness saint of Gurupá Mirim, set to take place four days from then: “We’re either going to do it after sunset, or in the morning, before ten, because nobody can stand walking from house to house carrying those saints in this heat,” he said—on the 28th day of Brazil’s hottest September in 63 years. According to INMET, the country’s weather service, in September the national temperature averaged 25.9o Celsius, or 78.62o Fahrenheit—1.7oC above the historical average of 24.2oC for this month.

It’s no different in the quilombos of Gurupá. The worry in Gurupá Mirim and Jocojó is that this summer will be a replay of the last, or even worse. “We’ve had a real tough time of it here. Practically all the quilombo communities were hit by the fires,” Ivanete says. Classes at the school where she works were suspended for several days because the children couldn’t tolerate the smoke. The fire spread rapidly, jumping from one side of the river to another, sparks swept across by the wind. “And there we were in that igapozão [floodplain forest] with our buckets, carrying water with pots and pans and in bottles. Men, women, and children.”

The same worry haunts Agenor Ramos Pombo, chair of the Gurupá Agro-extractive Cooperative of Quilombo Communities who Defend the Forest. Agenor, 58, is the son of Benedito Bentes Pombo, nickname Benipombo, who is remembered in Jocojó by everyone who talks about these traditions from the past. “My father was a folião with all the fellowships around here,” his son recalls. Benipombo’s main instrument, a raspador (literally, scraper), has been carefully stored as a relic in the community’s small church. Played by the lead foliões, the raspador, also known as a reco-reco, is made from a piece of dried bamboo stalk carved with a sawtooth pattern; when scraped with a wooden knife, the instrument produces a dry, percussive sound, providing a rhythmic background for the drumming and singing.

Benipombo’s main instrument, a raspador, or bamboo scraper, is kept in the community church, alongside wall fans, images of saints, and multicolored ribbons. Photos: Soll/Infoamazonia a SUMAÚMA

The front of the small church has wooden double doors with an arched lintel above, its navy-blue trim aged almost to gray. The interior is simple yet inviting, pews arranged in rows and exposed wooden beams on the ceiling. A statue of the Virgin Mary stands in an altar on the back wall, its ledge draped with multi-colored ribbons, a traditional element in expressions of popular faith. What’s new are the fans, two on each side wall.

In the past, Agenor says, church-goers could count on a breeze blowing through the windows all year round during novenas. Now they have to put up with the whir of the fans during Sunday mass: “They’re never not on, and everybody still sits there waving a sheet of paper.”

Zilda Duarte Viana, 45, and Perpétua Socorro dos Santos Pombo, 50, are the inseparable faith healers of the small village of Gurupá Mirim. The pair never misses a festival because they’re responsible for the ladainhas, prayers sung in a mixture of Portuguese and Latin. Attendees feel a sense of fellowship among themselves and a connection to the sacred as these short invocations to God and the saints are intoned over and over in a gentle, meditative rhythm and the faithful join the healers in singing the final verses.

Inside and outside the pink church in Gurupá Mirim, drums echo memories of faith from Africa, now distant in time as well as space. Photo: Soll/Infoamazonia a SUMAÚMA

Before Zilda Duarte and Perpétua Socorro came along, festivals in Gurupá Mirim depended on healers and foliões from other communities who came for the celebrations. “Gurupá Mirim didn’t have any faith healers. There were some in [Maria] Ribeira and Jocojó. We learned from them,” says Zilda Duarte. Now she and Perpétua are the sole leaders of the 12 nights of prayer during the Our Lady of Nazaré festival in October.

But it hasn’t been easy.

This is the worst time for praying, a summer like this, says Zilda. It’s so hot the fans have to be on, stirring up dust and quickly drying out the women’s throats. “Towards the end of the prayer, our voices are worn out, and we’re hoarse.”

Trees struggle, fruit rots, half-moons disappear

A gigantic Sumaúma tree in the center of the village affords respite from the heat because its immense crown throws a large swathe of shade. This tree, known in English as a kapok, is also a meeting point where a number of community activities take place. Under its boughs, a soccer game is played on a small field, while two men wind green Açai fronds around a pole made from the trunk of a Parapará, a species of Brazilian rosewood, which will be used for the festival of Our Lady of Nazaré.

The heat doesn’t appear to bother this majestic, centuries-old tree. It was born prepared for long periods of drought, thanks to its enormous buttress roots and ability to store a large quantity of water.

Shade cast by a centuries-old Sumaúma provides respite from the extreme heat in the village of Gurupá Mirim. Photos: Soll/Infoamazonia SUMAÚMA

But the Avocado, Cupuaçu, and Açai trees in faith healer Zilda’s backyard are struggling. Their fruit, says Zilda sadly, has been withering in the heat before it has a chance to ripen. “The Açai berries are all dropping before they’re even ready,” she explains.

Lying in the Amazon River delta, the Marajó is considered the world’s largest fluvial-maritime archipelago, bathed by the waters of the river and the Atlantic Ocean. In Gurupá, the Amazon creates a freshwater tide. As true throughout the archipelago, the rhythm of life, work, and gatherings in the communities of Gurupá follows the ebb and flow of the tide—there is the time of high waters, when rivers and tributaries flow strong and you can travel, and the time when you have to wait.

Boughs hang low over some stretches of the Gurupá Mirim River. The cold water caresses the paddler’s skin as they navigate these narrow, lowland channels in a casquinho or catraia, vessels big enough for only one. These channels are now drying up, stranding in time another important tradition of the saint festivals in Gurupá: meias-luas, or half-moons.

Devotees, foliões, and pilgrims balance in boats as they glide downstream while everyone prays, makes music, and sings to the honored saint during these floating processions. They travel the same route three times, back and forth, drawing a half-moon in the river water.

In Jocojó, people hold half-moon celebrations five times a year. The first is in January, honoring São Sebastião. Next comes the Holy Trinity half-moon, which can fall in May or June, followed by São João, always in June. Our Lady of Nazaré half-moon is celebrated in September in Jocojó. Last is the Our Lady of Good Remedy festival, held on October 15; it attracts the most pilgrims, who come to pay their promises.

Nowadays, at least two of these festivals—Our Lady of Nazaré and Our Lady of Good Remedy—are held without the half-moon procession.

“How can you have a half-moon when the river’s dry?” asks Ivanete Duarte.

When they could still travel the rivers during this period, devotees would come from other communities, paddling downstream altogether around five in the afternoon. “There was lots of excitement, big boats, all full,” she recalls.

Ivanete Duarte and her husband, Benedito, get emotional when they talk about the “high waters” during the former half-moon processions in the quilombo of Jocojó. Photos: Soll/Infoamazonia SUMAÚMA

João Ramos Fernandes, 66, remembers it well: “There were hardly any motors back then. So it was just paddles. Those bigger canoes, full of people, foliões, the saints. They’d paddle along. Now we only hold the half-moon in January, May, and June.”

The Jocojó and Gurupá Mirim are part of the Amazon River system, made up of direct and indirect tributaries connected with the many branches that feed into the main river, which this year is facing one of the worst droughts in over a century. According to a survey by Cemaden—a research unit within the Science Ministry that is responsible for monitoring natural disasters—1,133 Brazilian municipalities experienced severe drought conditions this September, Gurupá among them.

Etelvina: no legs, lots of pain, but still praying

Etelvina da Silva Duarte, a 78-year-old retiree, lives in the first house to the right of the mouth of the river in Gurupá Mirim. She’s a restless woman, with a piercing gaze and deep furrows on her face, like a map of Amazon islands among crisscrossing streams. Much to her frustration, she had no schooling. When she was little, watching the boats with the colorful lettering on their sides along the riverbank in Gurupá, she badly wanted to read. She managed to learn a bit in her adulthood. As we talk, the television chatters away in the background. Every now and then she turns toward the screen and squints to see what’s on.

In the 1970s, Etelvina and her husband, Benedito Ferreira, came to Gurupá Mirim, where they found a river to fish in, land to plant on, and a church to celebrate their faith in. Photo: Soll/Infoamazonia SUMAÚMA

Etelvina says her legs won’t take her to mass, festivals, or processions anymore. The pain keeps her from the little pink church at the top of the slope leading up to the village. “I worked a lot. I used to tap rubber, cut timber, cut straw…” What she has been left with is pain whenever she walks. But she has never stopped finding ways to express her faith. “When I go to bed, when I get up, I pray.” And she keeps Our Lady of Sorrow close by, just in case a prayer is urgently required.

Most of the houses in the community have one or two, if not more, small holy images perched on an altar or bookcase, above or below a TV set, or on a wooden stand in the kitchen. What matters is that the saint is there for daily prayers or for when a candle is lit to illuminate the path forward. In Etelvina’s home, the saint hangs in an old frame on the bedroom wall, protected by a sheet of yellowed plastic, a blue ribbon tied around it.

Spending more time at home now, Etelvina realizes the weather is changing. From her window, she notices the river getting lower every year. She also notices the change on TV, with its relentless airing of news stories about floods, forest fires, and other extreme weather events and natural disasters. “I get scared when there’s a storm. Because of all that’s happened out there.” She looks at the TV. “It didn’t used to be like this. We didn’t see so much of this. Now we see it there. It makes me nervous. When weather is brewing, I think about the things happening out there,” she says gloomily. She doesn’t seem to know what to do in the face of what she’s been witnessing. “All we can do is put up with it. Because God’s in charge, right?”

That’s not how Edir sees it. For this retiree, who lives on the other side of the river, if a future is possible, it must be ancestral. And this “messed up” climate has been caused by the destruction of Nature and by something that has been lost in how people relate to it. He says his father, a rubber tapper, taught him to do his work while respecting others and Nature. “My father worked with rubber, cutting Rubber Trees, extracting milky liquid from the wood, it never ended,” Edir explains.

When the Jocojó River isn’t dry, it reflects the branches along its banks and the vessels that serve as floating temples under the open sky during traditional half-moon processions. Photos: Soll/Infoamazonia SUMAÚMA

“Whatever you take from Nature will be missed down the road”

In Edir’s opinion, his father’s approach to work—using traditional techniques that respect the life cycle of trees—may be key to leaving something of the rainforest for future generations. “It wasn’t about killing off the wood, like today. Companies come in, chop it all down, within a month they’ve done away with everything in the area,” he says. “I’ve learned a lot from my ancestors. They knew if they took something from Nature, it would be missed, not just by them but by others down the road.” Edir also lived through a time of abundant game, fish, and trees. “My kids today don’t see any of this. They don’t even know some of the game. They don’t know what an Agouti or a Paca is. My grandchildren, it’s worse. My father used to say: ‘This here is such-and-such wood’. There was [this wood], and now there isn’t.”

“Learning” is a word Edir repeats a lot. He doesn’t understand why professors and researchers sometimes consult with him, asking questions about the history of Gurupá’s religious fellowships. “I hardly went to school, didn’t even make it to fourth grade. How am I going to teach a professor?” he wonders. He says this while keeping a caring eye on his 4-year-old granddaughter, Laila Brilhante Pantoja, who accompanies him during a demonstration of the drums and percussion instruments used in celebrations. Back when he was learning, he recalls, the system was stricter: “When we made a mistake, we were punished”; they made him kneel on stones. He’s not going to do the same to little Laila because he’s wise enough to know what should be learned from the past.

Ever since he moved to Gurupá Mirim Quilombo, more than fifty years ago, 89-year-old Benedito Ferreira dos Santos has watched the sky from the edge of the Gurupá Mirim River. Even though his vision is now so “cloudy” he can’t recognize faces, the old man can see, feel, and smell that the climate is different. That’s what he does every day, sitting in front of his blue house. Suspended above the floodplain on wooden stilts, his home is ready for the “big waters,” the heavy rains of the Amazonian winter, which last from about November to April.

Benedito says even the rains are different, “with lightning bolts that practically land inside your house.” And the scalding heat that used to arrive in September now rushes in a month earlier. “As they say in the Amazon, ‘I don’t know if the earth is higher or the sky lower, I just know it’s gotten hotter’.”

This is hell coming to Gurupá.

The video highlights traditions like ladainhas and festivals in Gurupá, where promises of faith and protection reverberate under a blazing sun

The product of a partnership between SUMAÚMA and InfoAmazonia, this story received the support of Voices for Just Climate Action (VCA), which works to amplify local climate action and seeks to play a central role in the global climate debate. InfoAmazonia is part of the coalition “Strengthening the data ecosystem and civic innovation in the Brazilian Amazon,” along with the Black House Association of Afro-Engagement, Puraqué Collective, PyLadies Manaus, PyData Manaus, and Open Knowledge Brasil.

Report and text: Soll

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum