Anthropologist Mary Allegretti is part of the history of Brazil’s socio-environmental movement in Brazil. Along with Chico Mendes and the rubber-tappers who fought for the forests where they worked in the state of Acre, she helped to formulate a proposal 40 years ago to create extractivist reserves, a new type of conservation unit that includes Nature and the people living in it. Allegretti attended the 29th UN Climate Change Conference, COP-29, in far-off Baku, Azerbaijan, to talk about an initiative that, she says, has given her renewed motivation. For the last year and a half, she has coordinated a project to train around 10,000 people living in the Chico Mendes Extractivist Reserve, which covers around 1 million hectares, to develop a future project to generate carbon credits. It is a pilot program that the National Council of Extrativist Populations could replicate in other extractivist reserves, so communities who want to implement projects can run them, rather than being swindled by “carbon cowboys.”

Allegretti pointed out that for decades residents in Acre’s community territories have lived “in the same conditions, with no investment in infrastructure, no access to education, no access to health.” The Chico Mendes Extractivist Reserve fell victim to the advancing deforestation clearing the land for cattle pastures. “So, how can you deny the communities access to a project that could provide investments when the government hasn’t managed to make investments?” the anthropologist and director of the Institute of Amazonian Studies argued during a panel at the COP’s Brazil pavilion. “We are convinced that good carbon products can be developed with communities playing a leading role.”

MARY ALLEGRETTI DISCUSSED HER PROGRAM TO INFORM RESIDENTS OF THE CHICO MENDES RESERVE ABOUT CARBON PROJECTS, WHICH GAINED GROUND AT THE COP. PHOTO: APEX BRASIL

A topic that causes discord among environmentalists, the carbon markets received a boost at the Climate Conference in Baku, which gave the green light to implementing the international emissions trading mechanisms proposed nine years ago in the Paris Agreement. These documents’ approval was the only moment that met with general applause at the conference’s last plenary session, which went from Saturday night, November 23, into the early hours of Sunday morning. Carbon credits that are able to enter the market under the supervision of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change are expected to have a higher value and help to pay for the climate transition.

Nevertheless, as Brazil’s environment and climate change minister Marina Silva put it, the emissions trading established in the Paris Agreement is an “important instrument,” but “not a panacea.” The mere possibility of receiving money from carbon credit sales cannot be confused with achieving the goal that was indeed the focus of the COP-29: defining a new climate finance goal to replace the US$ 100 billion per year promised by materially rich countries in 2009. According to these countries, this amount was finally reached in 2022, at which point they had disbursed US$ 115.9 billion. However, a study by the Oxfam organization showed that when high interest rates and projects unrelated to climate are subtracted from these loans, the amount left would be at most US$ 35 billion.

Based on the Climate Convention and the Paris Agreement, climate funding should be provided by historical polluters (essentially the United States, Europe and Japan) to the other countries, especially those with fewer monetary resources.

A commission of economists formed at COP-26, in 2021, estimated that US$ 1 trillion per year in external finance is needed by 2030 and US$ 1.3 trillion by 2035. This includes public and private money and does not include funding from China, currently the number one polluter, which will make voluntary contributions. The commission suggested that wealthy countries directly deliver US$ 300 billion per year by 2030, and then US$ 390 billion annually by 2035. The Group of 77, made up of nations in the Global South, proposed that this “inner quantum” of funding, as it was called at the COP-29, be US$ 500 billion each year. A statement from 15 economists and scientists from institutions in Europe and the US pointed out that the new finance goal “inner quantum” needs to be paid out starting in 2025, and not “by” 2030 or 2035, and it should be public money.

The historical polluters have always refused a stricter definition of what should count as climate financing, but the rest always insist that it should be public money, in the form of donations or loans with favorable conditions that do not increase poorer nations’ foreign debt.

Although the new goal has been under discussion for three years, long before denialist Donald Trump was elected in the US, rich countries only brought a figure to the table – agreeing to contribute US$ 250 billion annually – on November 22, which was supposed to be the last day of the COP-29. Things had gone, as environment minister Marina lamented, to “extra time in the second half.”

MINISTER MARINA SILVA INHERITED THE MISSION OF GETTING POLLUTERS TO PAY, OVERCOMING THE RAGE AND FRUSTRATION IN BAKU. PHOTO: MIKE MUZURAKIS/IISD/ENB

In the final agreement, the inner quantum of the funding, the amount to be provided “under the leadership” of the wealthy countries, was increased to US$ 300 billion dollars annually, but the text only stipulates a commitment to reach this amount in 2035. This sum corresponds to one-third of the United States’ military budget and doesn’t represent even twice the US$ 163 billion that African countries are paying in interest on their foreign debts this year. In addition, as many have noted, this US$ 300 billion will probably not even be enough to make up for inflation on the US$ 100 billion agreed to in 2009 once 2035 arrives.

And worse: the agreement approved in the early morning hours of November 24, to protests from countries like Nigeria, India and Cuba, says that the US$ 300 billion could come from “a wide range of sources, private and public.” China, India and Brazil will also end up contributing, since this amount will include money “mobilized” by multilateral banks, which are institutions like the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Asian Development Bank, of which the three countries are part.

European Commissioner for Climate Action Wopke Hoekstra, of the Netherlands, was jeered – with the diplomatic jeer of throats being cleared – while he gave closing remarks in Baku. Yet not even this stopped him from being explicit: “We are also seeing a historic expansion of the very important role of multilateral development banks (…). This simply will bring much more private money [to] the table. And that is what we need.”

In short, COP-29’s main agreement hands the salvation of life on the planet over to private investors, who are not the ones who signed agreements to try to stop the climate emergency.

Brazilian Mariana Paoli, who has been following the finance issue since 2009 for Christian Aid, an international organization, provided an exact comparison. “Populations in the Global South came to the negotiations in need of a lifeboat, but they were given a board to cling to.”

Mariana recalled that there are no profits to be made from adapting to climate change and fixing damage incurred by the extreme events it causes, which is why these countries don’t draw money from companies. In Brazil, for example, the federal government estimates spending nearly R$ 100 billion (or nearly US$ 17 billion at the current exchange rate) this year on flooding in Rio Grande do Sul.

What particularly annoyed poorer and island countries was how the European bloc spent COP-29 demanding ambition from other nations. Tunisian economist Fadhel Kaboub, with the Power Shift Africa organization, was livid. “Africa’s accumulated emissions are less than 4% of global emissions. Some countries pollute much more and have a debt to pay. If you owe, you pay. You don’t lend money, you don’t say what this country should do with the money, you don’t invest in a country to take the minerals for yourself.”

The big battle in Belém

In the end, the problem is that substantial and immediate finance was a precondition to make the new targets to cut greenhouse gas emissions ambitious. According to the Paris Agreement, all the countries must submit these targets by February 2025, prior to the COP being held in November, in Belém, and these targets will run until 2035.

The financial agreement made at COP-29 determines that it is up to Azerbaijan and Brazil, the host of the COP-30, to perform the miracle of circumventing the disbelief and rage prevalent in Baku. Over the coming months, the two countries will have to submit suggestions on how to multiply this US$ 300 billion in order to reach 2035 with the US$ 1.3 trillion estimated as necessary to try to contain the temperature’s rise on the planet to 1.5 degrees Celsius, in relation to the period prior to the Industrial Revolution.

The most direct way to raise this money would be to “get the polluters to pay,” as suggested by the UN’s secretary-general, António Guterres, and repeated by Brazil’s climate change secretary, Ana Toni. This means not depending so much on countries’ regular budgets and on establishing specific taxes and taxing the super-rich, fossil fuel production, aviation, and maritime transport. This will likely be the biggest battle in Belém.

However, it is not true that a there is a general lack of budgetary space – the European Union’s main claim in denying a more appropriate contribution. Priorities are the issue. Oil, gas and coal, which are mainly responsible for saturating the atmosphere in pollution, continue to be treated like kings. In 2022, they received US$ 7 trillion in government subsidies, according to the International Monetary Fund – China, the USA, Russia, the European Union, and India provide the biggest subsidies. In Brazil, these subsidies reached R$ 81.74 billion (or around US$ 14 billion in today’s money) in 2023, according to the Institute of Socio-Economic Studies, which calculates this amount each year.

OIL PLATFORMS IN THE CASPIAN SEA, ALONG WHOSE SHORES THE CAPITAL OF AZERBAIJAN SITS, THE THIRD COUNTRY WITH PLANS TO RAMP UP PRODUCTION THAT HAS HOSTED A COP. PHOTO: TOFIK BABAYEV/AFP

In fact, none of the documents approved in Baku mentions the commitment undertaken by the countries at the COP-28, in Dubai, to gradually eliminate fossil fuels. Deciding on how to put this decision into practice is another job that was left for Belém. For COP-29, Brazil had proposed discussing a timeline for this elimination, but with rich countries starting first – the United States, where Trump takes office on January 20, is currently the biggest producer.

Azerbaijan is the third consecutive COP host that plans to bolster its oil production. Brazil will be the fourth. The former Soviet republic of 10 million people found oil and gas bubbling up from the ground back in the nineteenth century. It drilled the Caspian Sea, along whose shores Baku sits, and worships this fuel, which is paid homage in monuments and edifices. The cheap gasoline flattens transportation prices. Yet what distinguishes Azerbaijan is its dependence on income from fossil fuels, which account for over 90% of its exports, with Italy as its biggest customer. In terms of oil volume, the country produces equal to one-fourth of Brazil’s oil and one-third of Norway’s oil.

Despite its enormous wealth, Norway also did not submit a plan to bring down oil production, said Matilde Angeltveit, an environmentalist with the Norwegian Church Aid organization. She was critical of her country, saying that “the burning of the fossil fuels we export produces ten times more emissions than our own domestic emissions. Obviously we should assume responsibility for this too.”

Far from the front lines

The COP-29’s decisions were even more frustrating in light of the reports given at the conference by those on the front lines of the climate disaster. Sinéia do Vale, an ethnic Wapichana woman, who was elected co-president of the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change (also known as the Indigenous Caucus), has for over 30 years been part of the Indigenous Council of Roraima, which has a fire monitoring system in that state’s Indigenous Territories. “From last year to now, we’ve had irreparable fires,” Sinéia says. “Eighty percent of the Lavrado [a biome with vegetation similar to the Cerrado] burned, and 70% of these fires came from outside the Territories. This has been recurring for at least the last three years,” she added. Roraima is experiencing growth in soy monocrops.

ELECTED CO-PRESIDENT OF THE INDIGENOUS CAUCUS AT THE CLIMATE CONVENTION, SINEIA DO VALE TALKED ABOUT HOW RORAIMA’S LAVRADO IS BEING DESTROYED BY FIRE. PHOTO: PEPYAKÁ KRIKATI/COIAB

During her visits to the Chico Mendes Extractivist Reserve, Mary Allegretti saw everything “from rains where the houses are immersed to droughts two months later where there’s no water to drink.” Ane Alencar, the science director at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute, said she is “horrified” by “the huge increase in standing forest area affected by fires because of climate change.”

Fire Monitor data released during COP-29 shows that 6.5 million hectares of forests in the Amazon were affected by fires from January to October of this year, a 670% percent increase compared to the same period the year before. This is an area larger than the 5.3 million hectares of pastureland affected by fire – under normal conditions, fires started by human action have a greater impact on these pastures where vegetation has already been cleared. Unlike fires connected to deforestation, which are set after the trees are cut, blazes in native biomes are not included in countries’ greenhouse gas emissions inventories. They are only included if the fire consolidates a “change in land use” there, with a loss of vegetation in burned areas and a reduction in carbon gas stored by plants through photosynthesis.

With the warning signals multiplying, Brazil’s Environment Ministry and diplomats insisted in Baku that there is no other solution except to keep working toward “mission 1.5,” as the effort to contain the rise in the Earth’s temperature has been called since the Dubai COP. This will require a much greater and much faster effort from countries to cut their greenhouse gas emissions.

Physicist Paulo Artaxo, a professor at the University of São Paulo and a member of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said it will be impossible to fulfill the Paris Agreement, which sets a maximum limit of 2 degrees on temperature rise, if current emissions remain unchanged. Artaxo, who was in Baku, mentions a report released by the UN Environment Programme just before the COP-29. “It’s very clear and explicit in the report on the emissions gap that it’s absolutely impossible, with the current emissions, to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Actually, with current emissions and current emissions reduction policies, we are moving toward a temperature rise of 3 degrees Celsius”, he said.

The statement put out by 15 scientists and economists estimated that this scenario, which puts Earth close to a climate cataclysm, will only be avoided if the inner quantum of funding from wealthy countries is immediately increased to US$ 256 billion. In addition to the public money, this money should be new; that is, funds already allocated to multilateral banks or foreign aid cannot be counted. This “is not just a moral obligation (…) or charity,” the statement reads, but rather is in the interest of these same historical polluters and the world.

One of the problems nagging at international agreements on the climate emergency is that they do not have any clauses forcing countries to fulfill the promises they make. Changing this was one of the reforms suggested by international leaders, including Brazilian scientist Carlos Nobre, in a letter released during COP-29’s first few days. The letter says it’s time to “deliver on commitments undertaken” and halt endless negotiations.

There are other proposals along these lines, including one from President Lula. While COP-29 was still happening, Lula hosted the G-20 summit of the world’s largest economies in Rio de Janeiro. He then suggested creating a UN Council on Climate Change, to speed implementation of the Paris Agreement. Ottmar Edenhofer, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, in Germany, proposed that countries begin negotiating in smaller groups, based on a swap – the wealthy North countries would tax fossil fuels to finance countries in the Global South, and in exchange they would require them to cut their emissions.

FAILURE TO ACT QUICKLY WILL MEAN THERE IS NO WAY TO KEEP THE EARTH’S TEMPERATURE FROM RISING, MAKING FORESTS MORE VULNERABLE TO FIRES. PHOTO: EDMAR BARROS/AMAZÔNIA LATITUDE

Calculations for forgotten forests

Carlos Nobre went practically straight from the biodiversity COP, which ended in early November in Cali, Colombia, to chilly Baku. He didn’t stop doing math. “The science shows that we would need to restore 6.7 million square kilometers across the planet to remove some 5.6 billion metric tons of carbon gas per year to lessen the risk of climate change,” the scientist calculates. “One hectare of restored tropical forest removes 12 to 18 metric tons of carbon gas per year, for around 40 years,” he continued. If each ton removed became a carbon credit, and this credit reached a value of US$ 100, he concluded, this could represent a minimum sum to keep the forest and scale up restoration.

However, Nobre added, it is not enough to count the benefits provided by the forest based only on the carbon it removes. “You would need to have a market of all the ecosystemic services, like regulation of rainfall regimes. Maintaining biodiversity is essential, including to save humans from epidemics and pandemics.” Yet in Cali, there was no agreement on financing for conservation and recovery of biodiversity.

In Cali and in Baku, the Brazilian government again presented its Tropical Forest Forever Facility, which aims to compensate forest countries for each hectare conserved, moving away from the carbon market rationale. The fund was mentioned in the G-20 statement and in the memo from the meeting between Lula and China’s president, Xi Jinping. The idea is for it to be up and running before the COP in Belém. It was initially forecast to raise US$ 125 billion between public and private investments. For Nobre, this is still a modest number. “The forest would need to be appreciated much more,” he said.

Like with the elimination of fossil fuels, none of the agreements approved in Azerbaijan picked up the second big commitment signed in Dubai, which is for countries to boost their efforts to stop and reverse deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. Brazil, which intends to restore 12 million hectares of native biomes by the end of this decade, had proposed “operationalization” of this commitment, with financing planned for restoration and instruments to facilitate access to bioeconomy products and foreign markets. This issue failed to find a home in any of the documents, including because one of them, a dialog document on decisions in Dubai, was not approved and will have to again be examined in Belém.

While looking for direct financing for forests, the Brazilian government also indicated the possibility of turning to the carbon trading mechanisms in the Paris Agreement.

There are two mechanisms. One deals with inter-country trading of so-called Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes, or ITMOs. In this case, a country that reduces its emissions beyond its commitment could sell its excess to another country. The UN will build a system of records for all the countries to provide accountability on exchanges, but specialists were unhappy with the lack of a stronger plan to punish governments that sell bad ITMOs, ones that don’t actually represent a cut in emissions beyond what was planned. At the COP-29, Brazil said it may use this instrument, if it has a surplus of cut emissions and considers the ITMO value to be high enough to finance wider domestic decarbonization. At the same time, the country promised to report on whether bad ITMO sales occur.

In the second mechanism, which is precisely the carbon market, companies and governments could buy credits to offset their emissions. A supervisory body connected to the Climate Convention will establish which methodologies for generating credits will be accepted in this market. This definition will be important to orient the regulated carbon market approved by Brazil’s Congress during COP-29. In this market, companies that are major polluters will be able to offset some of their emissions with carbon credits. To enter the official system, the methodologies behind these credits will also have to be approved. Being accepted in the regulated market, whether in Brazil or through the Climate Convention, means a higher worth.

Today, in the so-called voluntary carbon market, which is unregulated, forest credits are worth far less than the US$ 100 Nobre mentions as being reasonable. In the agreement between the state of Pará’s government and the Leaf Coalition, comprised of wealthy countries and large companies, each credit generated to reduce deforestation will be sold for US$ 15. The money raised won’t be a “silver bullet,” the executive secretary of the Interstate Consortium for Sustainable Development of the Legal Amazon, Marcello Brito, said while in Baku. “Only discussing carbon credit and not biodiversity is a mistake.”

The credit dividing Indigenous people

In Pará, Indigenous leaders are split over the state’s carbon program, and it reached the COP-29. The leaders of the Federation of Indigenous Peoples of Pará are participants in the program. Prior to the sale of credits, set for late 2025, original peoples, extractivists and Quilombolas will be consulted on the amount of money that will reach communities caring for the forest and on how it will be invested.

Ronaldo Amanayé, treasury coordinator for the Federation of Indigenous Peoples of Pará, said the federation has traveled the state to bring information to the Territories and listen to their demands for the consultation. “We have a small group that is completely opposed because it is being stuffed with disinformation through their ears,” he charges. Avanilson Karajá, the treasury coordinator at the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon defended the state programs. “There is still this view that the Territory will be sold, that they won’t be able to do any planting, but it’s a policy that could resolve some problems within the Territories,” said Avanilson, who hails from Tocantins, a state that also intends to sign an agreement with the Leaf Coalition.

The most vehement opposition to Pará’s program comes from Alessandra Korap, with the Pariri Indigenous Association, who was also in Baku. She complained that the Federation of Indigenous Peoples of Pará held a meeting on the matter in the city of Jacareacanga, and not in the territory held by her people, the Munduruku. “Without having a foundation, without having talked to the women, without having talked to the children, to the pajés [healers], it doesn’t work for us. It needs to be discussed much more,” she said.

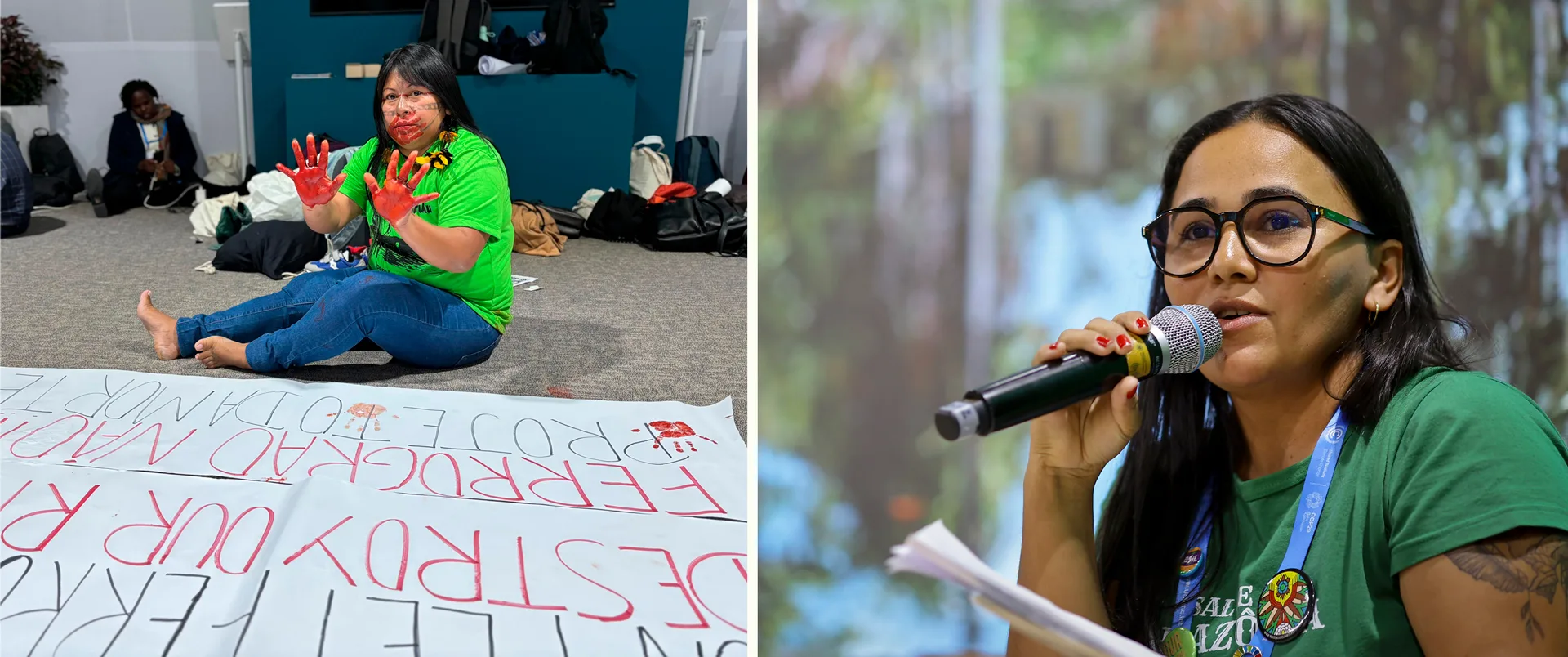

ALESSANDRA KORAP (LEFT) PROTESTED AGAINST THE FERROGRÃO RAILWAY AND CRITICIZED THE CARBON MARKET, AS DID CLEIDIANE VIEIRA. PHOTOS: ANA MATHIAS/MAB AND APEXBRASIL

Alongside Alessandra, Cleidiane Vieira, with the Movement of People Affected by Dams, was also critical. “We at the Movement of People Affected by Dams consider [the carbon markets] to be one of the false solutions that capital has put forward to get out of the crisis. The climate crisis is being financialized and a lot of market is needed for all of the companies,” she stated. “If there is a forest, it’s because the peoples that are there cared for it. Now they want to sequester this preservation to continue polluting.”

Cleidiane’s argument matches one made by organizations like Greenpeace, who see the Paris carbon markets as handing survival to polluting businesses, like the oil industry. “Worse, they’re a smokescreen for the lack of progress in real solutions for climate financing,” said An Lambrechts, a specialist on biodiversity policy at the NGO.

Mary Allegretti, the anthropologist, recognizes that there is “plenty of scheming” in carbon markets, but said she is willing “to work to not have” this and avoid what she sees as the worst scenario: one where young people, who now barely remember the struggle of Chico Mendes, killed in 1988, leave the territory because they fail to see any perspective for their lives. “If the people living in the Amazon today, especially young people, decide to leave because they didn’t find a local solution, the forest will disappear. The families go away, the land-grabbers come in,” says Mary.

Big ag and the little guys

The side events at the COPs, held outside of the negotiating rooms, serve as a showcase for countries to try to attract investments. The Lula administration’s delegation had 35 agribusiness and trade group representatives, a conference record. Activities connected to ag are among the biggest beneficiaries of tax exemptions in Brazil, according to a list released in November by Brazil’s internal revenue service. This area’s main program presented by the government in Baku was the conversion of degraded pastures, which is supposed to be detailed by the Agriculture Ministry and, for now, relies on support from the cooperation agency of Japan.

Rodrigo Lima, with the Agroicone consulting firm, collaborated on creation of the program, which is in the cost assessment phase. At COP-29, he explained that Brazil has 40 million hectares of highly degraded pastures. Of these, 27 million are high-priority for conversion to agroforests, forests, agricultural crop areas, and recovered pastures. The country, Rodrigo says, has 2.5 million estates or rural properties dedicated to livestock farming, 2.2 million of which cover up to 200 hectares. The latter, he stresses, are the biggest challenge, since farmers do not have resources to recover land on their own, unlike the industry’s big actors.

The pasture conversion program will require that beneficiaries commit to completely ending deforestation, even when it is authorized under the Forest Code. Moreover, only farms with a current registration in the Environmental Registry of Rural Properties and with no deforestation after 2008 will be able to benefit.

In Baku, Carlos Ernesto Augustin, an ag executive and special adviser to agriculture minister Carlos Fávaro, said that Brazil can double its agricultural production without deforesting. “We have land for another 20, 30 years,” he said. This message hit a sour note on another panel which included Rodrigo Justus, with the National Confederation of Agriculture. “After a point, you can use however much fertilizer you want, irrigate as much as you want, because productivity has a limit,” said Justus. “This discussion needs to permeate this type of debate, or else the sky is the limit, and we’re going to believe that we’re going to take earth out of production, forgetting that humanity is always growing its population.”

The poor man’s agriculture industry representative in the government, the Agrarian Development and Family Agriculture Ministry, released a smaller program at the COP, for family farming and rural settlements. Moisés Savian, the ministry’s secretary, said that 21 settlements will initially be covered by the National Productive Forests Program. It is little, because according to the numbers shown by Savian, the Amazon alone has 3,041 settlements, with 561,000 families, many holding individual lots. They occupy an area of 57.9 million hectares, an astounding 27 million of which are deforested and have turned to pasture.

RODRIGO LIMA AND MOISÉS SAVIAN DISCUSSED PROGRAMS TO CONVERT DEGRADED PASTURES AND PREVENT MORE DEFORESTATION. PHOTOS: APEX BRASIL

Family farming is a complicated category in Brazil, explains Maurício Alcântara, of the Regenera Institute: “It’s more of a political than a technical category.” It includes everything from small farmers working for agribusiness to those who adopt agroecological practices. For them, accessing credit is more complicated, says Rio Grande do Sul native Gerson Borges, who attended the COP-29 as part of a delegation with the Small Farmers Movement. “This group, which we are part of, farms with bio-inputs and not with chemical fertilizers, it works with heirloom plants and coexists with the biome, in agroforestry systems, for instance,” said Gerson.

There are around 10 million small farmers in Brazil, working on properties covering up to four fiscal modules – a size classification that varies according to the region and even the municipality. For this harvest, contracts with the National Program to Strengthen Family Farming, the industry’s credit program, totaled R$ 1.6 million, according to the government. Leila Meurer, an activist with the same movement who came from Ariquemes, Rondônia, explains the difference: “These products supply the local economy and, because there is no concentrated income, they have a hard time making payments and providing the guarantees the banks require.” Isabel Garcia Drigo, with the Institute for Forestry and Agricultural Management and Certification, said the rationale behind rural credit does not always meet small farmers’ needs: “There is money for investing, which is for purchasing machinery, cattle; but there is less for defrayal, which is important when paying for a fence, for example.”

Like Gerson and Leila, there were dozens of small farmers from around the world in Baku, part of an increasing debate at the COPs over changing food production systems. These are discussions that progress outside of the negotiating rooms. Inside the Climate Convention, a working group known as the Sharm el-Sheikh group approved the creation of an online platform in Baku, where countries will be able to show what they consider to be good agricultural practices. “It’s a portal for sharing practices and finding partners and financing,” said Marcelo Morandi, with the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation.

LEILA MEURER REPRESENTED THE SMALL FARMERS’ MOVEMENT AT THE COP, WHERE SIDE EVENTS DISCUSSED CHANGING FOOD SYSTEMS. PHOTO: APEX BRASIL

Afro-descendants persist and Indigenous peoples are betrayed

If those advocating for ecological agriculture are still hoping to pop the bubble, the negotiations at COP-29 were marked by setbacks and obstacles. Marina Silva listed some of them, piling more tasks on Belém: “There are other themes that we are extremely committed to, like the issue of human rights, women’s rights, recognizing the contribution of the Afro-descendent community, and synergy between the COPs [on climate and biodiversity]. Unfortunately, we’ve yet to see these topics included, but the appropriate work on them will be done at COP-30,” she promised.

Ever since COP-27, in Egypt, Brazil’s Black movement has been growing its participation at the climate conferences. One demand is for documents to incorporate the uniqueness of Afro-descendants, alongside already established mentions of Indigenous peoples and local communities. Leticia Leobet, with Geledés – Black Women’s Institute, said the Brazilian government has responded well to the demand, as indicated by Marina’s words. “But what is insufficient are the articulations Brazil has made with other countries to create consensus around racial language,” Leticia added.

Specifically, resistance from African nations must be overcome, which have different causes according to the context of the discussion, she says. At the Cali conference, the African group ended up supporting a document officially recognizing the participation of Afro-descendent communities in conserving biodiversity. “We saw some resistance initially, because of an understanding that including Afro-descendants meant splitting up the financial pie. In other contexts, we’ve noticed that this resistance is more of a symbolic barrier, because countries in the African group are often already included from the perspective of ethnicity,” Letícia explained.

The Black movement is following other documents from the COPs regarding the adaptation to climate change. Brazil is also discussing its industry-specific policies to adapt as part of the Climate Plan, which should be ready in 2025. At a debate in Baku, Mariana Belmont, who is also with Geledés, was crystal clear. “It’s no use sprinkling the words gender and race into all of the government’s policies. Many environmental policies led to people being removed from Black territories. When we look at the preface of the strategy to adapt, the words are there. The question is whether the resource will reach the periphery for implementation,” she says. Mariana, who is from São Paulo, said her reference for the Belém COP will be the Center of Black Studies and Defense in Pará, directed by Nilma Bentes and Zélia Amador, long-time leaders in the anti-racist movement in the Amazon.

The main document on adapting approved in Baku contains meager advances, says Thaynah Gutierrez, with the Network for Anti-Racist Adaptation. The mention of human rights was kept and during negotiations the number of indicators used to measure countries’ progress toward adaptation goals was reduced from an initially proposed 9,000 to 100, providing a sharper focus. Even so, these indicators are voluntary, and each country could make their own list out of the 100 chosen.

THE ANTI-RACIST MOVEMENT AT THE CLIMATE COPS, AND LETICIA LOEBET WORKS TO RECOGNIZE THE UNIQUENESS OF AFRO-DESCENDANTS. PHOTO: APEX BRASIL

It is normal for civil society activists to celebrate minor victories like this, especially after a conference where the document on gender and climate excluded a reference to violence against women. Due to pressure from Russia and Arab countries like Saudi Arabia, any language suggestive of LGBTQIA+ rights was also modified.

Members of the Indigenous Caucus, led by Brazilian co-president Sinéia do Vale, were outraged upon leaving the COP-29. In the agreement on climate finance, the main agreement approved at Baku, a mandate was removed for countries to respect, promote, and consider the rights of Indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, refugees and other “vulnerable” groups. Instead, a paternalistic appeal was included for countries to promote inclusion and extend benefits to these groups. It stood in contradiction to the events of a little over a month earlier, at the biodiversity COP in Cali, where the Indigenous people guaranteed the creation of the first permanent subsidiary body in UN conferences to discuss their rights.

“There is nothing to celebrate,” read a statement from the Caucus, underscoring that Indigenous people should be recognized as “crucial and equal partners” and “rights holders.” The statement also criticized the funding in the agreement: “While we urgently need direct and equitable access to climate finance (…), we reiterate that we reject the financial colonization that comes from loans and any other financial mechanisms that perpetuate indebtedness of Nations who have contributed the least to climate change.”

Brazil’s Indigenous people, as well as those from every Amazonian country, will be out in force at Belém. For the first time in four years, the conference is being held in a democratic country. There will be protests on the street, outside of the controlled space where negotiations are held. They intend to seize the opportunity and crank up the pressure. The number of things to do just keeps growing for Belém.

THE CONFERENCE IN BAKU RAISED MISTRUST IN THE PROCESS AT THE CLIMATE COPS AND LEFT BRAZIL WITH A STACK OF THINGS TO DO IN BELÉM. PHOTO: APEX BRASIL

COP-16 coverage by SUMAÚMA is done in partnership with Global Witness (@global_witness), an international organization working since 1993 to investigate, expose, and create campaigns against environmental and human rights abuses around the world.

Report and text: Claudia Antunes

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum