Belém didn’t declare official mourning nor were flags lowered to half-mast but the city felt collective grief when the mammoth crown of a kapok tree, or sumaúma in Portuguese, collapsed in the downtown area across from Nazaré Basilica, where the Our Lady of Nazareth procession ends each year. Estimated to be nearly 200 years old, the tree was famed for its astounding size and beauty, for hosting flocks of parakeets that pass through the capital of Pará on their summer migration, and for long bearing witness to countless stories and lives.

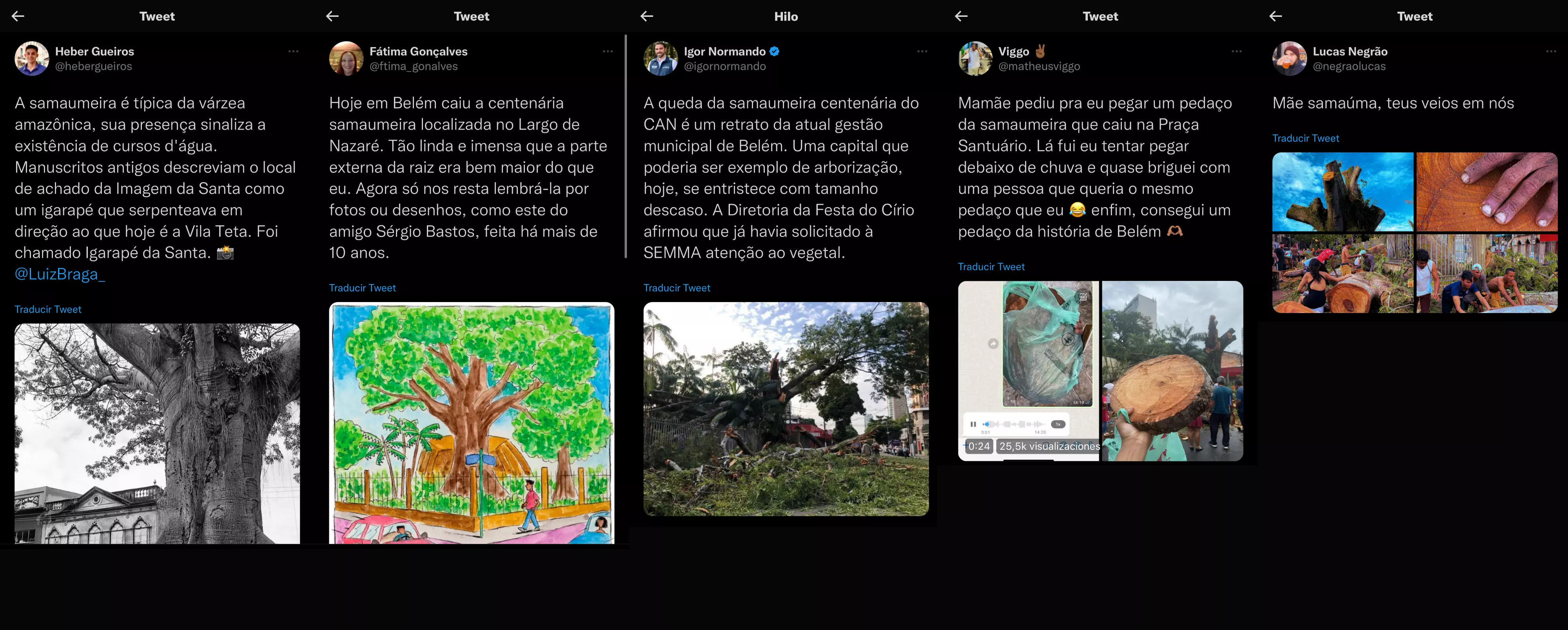

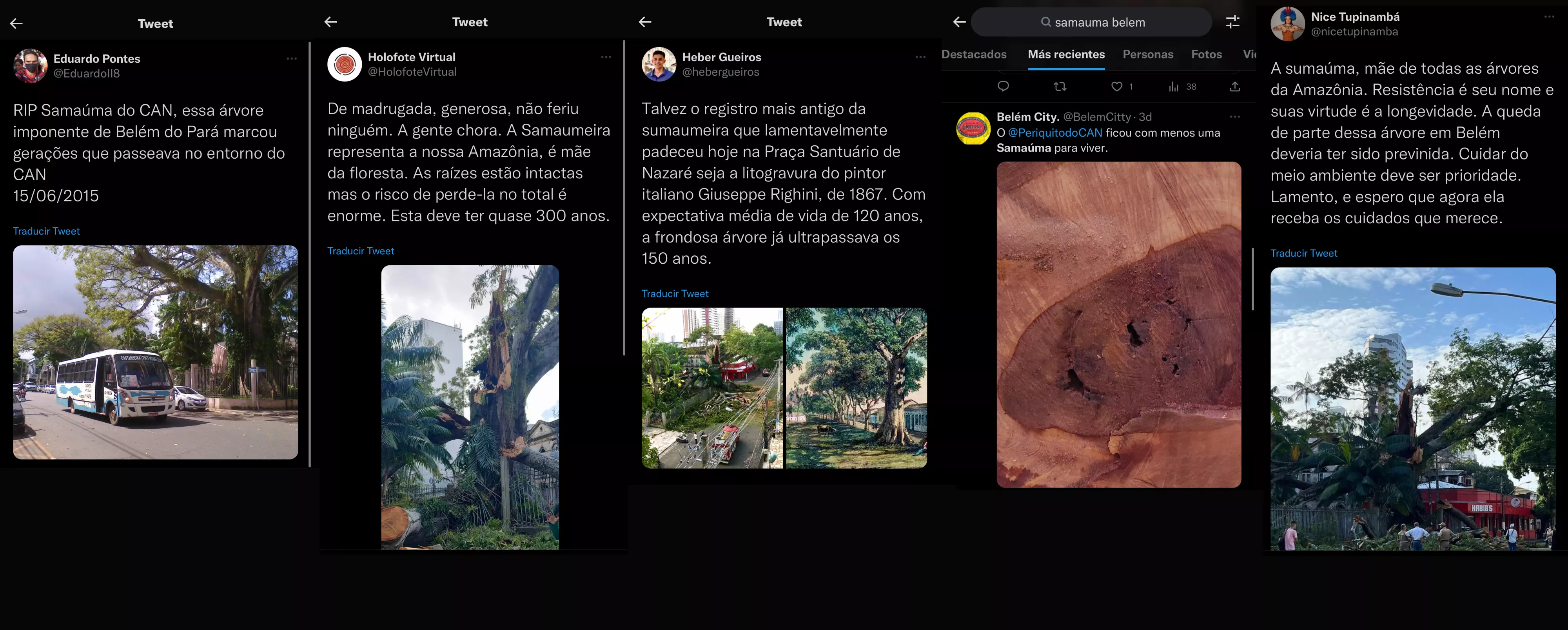

The bulk of the tree’s branches crashed to the ground in the early morning hours of February 6, timing that may well have prevented greater damage, given that the kapok tree stood in a busy, central region of the city. At any other time of day, a falling limb might have hit many passersby. One resident said on social media: “In the early morning hours, generously, it didn’t hurt anyone. We are weeping.” Security camera footage capturing the moment was played repeatedly on television and social media. By morning, the troubling news had swept across the city, as residents near and far streamed to the site, where they stared in a mixture of shock and sadness at the remains of the kapok, as if they were paying tribute to a beloved public figure lying in state. And they were.

Fallen branches from the sumaúma (kapok) tree that collapsed in the center of Belém, capital of the state of Pará. Photo: Celso Rodrigues

The Belém Department of the Environment sent in teams to cut up and haul off the massive branches, an operation requiring three days to complete given the size of the kapok. Members of the public who attended this unusual farewell asked city workers for a piece of the tree’s body to take home. Word soon got out that slices of the kapok were being given away. Many people left the location as if carrying a trophy—a piece of the city’s memory and something concrete that embodied their own remembrances of this beloved tree-person. Some took not one but several pieces to share with family and friends. In the midst of the commotion, information also began spreading that cuts of the wood were being sold. The Belém municipal government reacted by tweeting that the illegal sale of lumber is an environmental crime and that the city was distributing bits of the kapok for free in response to “heartfelt requests by people who wanted to have a piece of the tree as a memento.”

Reproduction: Twitter

Drawings, photos, and memories of the kapok tree flooded social networking sites. Some posted an image of a wood engraving from 1867 by Italian painter Giuseppe Righini that proves this tree-person was more than 150 years old. The visual artist Lucas Negrão shared images on Twitter and Instagram where locals are seen touching the fallen branches, with the caption: “Mother samaúma, your veins in ours.” In her post of a drawing depicting the ancient kapok in all its might by Sérgio Bastos, a famous local artist, the journalist Fátima Gonçalves lamented the fact that now “all we can do is remember it through photos or drawings.”

SUMAÚMA wanted to discover why the tree that lends its name to our journalism platform has inspired such love. The kapok, or Ceiba pentandra, has a few names in Portuguese, like sumaúma, samaúma, samaumeira, and samaumeira, and it is also referred to as queen, mother, and grandmother. In the forest, its life expectancy averages 500 years—about the age of what we call Brazil—while in urban settings, the number is 120. But one of the most famous specimens in the Brazilian Amazon, known as the Vovó, or Grandmother, which stands in Tapajós National Forest in western Pará, is estimated to be about one thousand years old.

Everyone knew the tree in Belém as the “CAN kapok,” after the Portuguese acronym for the Nazaré Architectural Complex, as the square was called before being rebaptized Praça Santuário de Nazaré. This giant was neither the largest kapok nor the only one in this spot, where three more remain. But the tree that toppled on February 6 was perhaps the most famous, since it was located right behind the bandshell, a prominent position where all eyes turned during every performance on stage. After giving her students a class on what she terms “emotional ties to the forest,” the biologist Flávia Araújo Lucas, professor at Pará State University and plant specialist, talked to me about the feelings stirred by this particular tree-person.

“I used to go there a lot. I was with a dance school, and we’d do shows in the bandshell, so we really feel connected to that square. We have emotional ties to plants, emotional ties to the environments we’re familiar with, that were from our childhood, that we played with,” she says. “The CAN kapok, that was painful for me. It was like a relative of mine, someone from my family. A lot of people felt that way. They’re living beings. Not just some component of the landscape; they’re what make us feel like nature.”

Reproduction: Twitter

Flávia works with backyard revitalization in the metropolitan region of Belém, including the numerous islands that make up over half the city’s municipal territory. She explains that while the kapok tree is found not only in the Brazilian Amazon, it is an iconic tree in the region, where it grows on dry land but primarily in seasonal floodplains. “They’re iconic because these trees tell our history and also the history of South America,” she says. “There are many myths and rites surrounding the kapok. It’s a plant full of symbolism, and the Indigenous and ribeirinhos [members of traditional forest communities] identify strongly with it.”

Glenn Shepard, an anthropologist and researcher with the Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi who works in the area of ethnoecology, agrees. He is one of the organizers of the virtual exhibit Floresta Sensível, which gives viewers the experience of being “immersed in the flavors of the forest.” With scientific, cosmological, and mythological information on the forest species that are part of the museum’s zoo and botanical garden, the exhibit is like an online walk where visitors can learn more about local plants. In Glenn’s opinion, it is the majesty of the kapok that captivates visitors. The tree, with its vast, sprawling crown, can reach a height of nearly 200 feet (60 m.). Most notably, its immense buttress roots seem to embrace everyone who approaches. “With its buttress roots and expansive crown, it feels like a portal. Its branches are so big that harpy eagles [the largest Amazonian birds] build their nests there. So it’s a sheltering tree.”

The Environment Department of Belém sent teams to the site to remove the huge branches, in an operation that took three days. Photo: Sandro Barbosa

The kapok owes its significance to more than just its stateliness and beauty. The tree plays a fundamental role in the origin myths of several Indigenous groups. “For many Amazonian groups, the sky was closer to the earth in mythological times. You could climb a tree to get there, and the tree that held up the sky was often a kapok,” Glenn says. In other traditions, the kapok represents the structure of the Amazon’s mighty rivers with their dozens of branches and tributaries, much like the tree.

Representing the connection between earth and sky and also between the world of the living and the spiritual world, the kapok is an important communication channel in Amerindian shamanism. The museum’s virtual exhibit tells the story of the shamans of the Peruvian Amazon, who receive their powers by mixing the bark of the tree, which they call lupuna, with ayahuasca. According to the exhibit, “In Pará, the Gavião Parkatêjê people use kapok trunks in their log races, which along with archery games are part of important initiation rites for new warriors. In Acre state, kapoks also appear in the cosmology of the Arara Shawãdawa as part of this people’s origin story. A hawk that hunted children lived in a big kapok. After a human killed the hawk, this people rose out of its feathers.”

For the Ticuna people, of Amazonas state, “at the beginning of the world, a gigantic kapok (wotchine) closed over the earth, so there was no light. When the brothers Yo’i and Ipi threw seeds from a nitta tree (tcha) into its crown, they noticed a huge southern two-toed sloth holding the kapok branches fast to the sky. As they continued throwing seeds upward, the stars appeared, but still there was no light in the world. They tried to topple the tree with the help of all the animals in the forest, but they failed, even with the woodpecker’s assistance. So the brothers decided to offer their sister Aicüna in marriage to anyone who could throw fire ants into the eyes of the sloth holding the kapok’s branches fast to the sky. A small squirrel (taine) managed to climb the tree, throw the ants, and make the sloth set the sky free. The tree toppled and light spilled over the world. The Solimões River came into being from the fallen trunk, while its branches made other rivers.”

At the same time that the kapok possesses such deep cosmological meaning, when the tree grows in floodplains, its monumental roots can absorb and store hundreds of gallons of water a day, pumping up groundwater and releasing it into the atmosphere to form what science calls atmospheric or flying rivers, believed to be responsible for moisture that travels across the Brazilian landmass. “So ecologically and scientifically speaking, it does the job of connecting rivers, earth, and sky, quite literally, through this cycle of waters,” says Glenn. The kapok is related to another tree likewise filled with symbolism and meaning, native to the African continent: the baobab. These two trees belong to the same botanical family and have similar structures, including buttress roots. In Africa, the baobab also ties earth to sky and the world of the living to other worlds.

Glenn says he has seen buttress roots serve as a communication vehicle in the forest. When struck, these roots produce sound vibrations that travel great distances and can announce, for example, the arrival of visitors. But this is not the sole reason the kapok is the forest’s internet. The tree can scatter its own seeds, which are wrapped in a floss-like fiber similar to cotton that allows them to float for miles, ensuring reproduction. Furthermore, the fibers are water-repellant, which makes them resistant to the steady rains of the Amazon forest. Indigenous peoples wrap their hunting blowguns in the kapok’s seed-hair fiber for this reason. The non-Indigenous have likewise come to incorporate this ancestral technology, using it to protect moisture-sensitive equipment and to clean up petroleum spills, as the water-repellant fiber absorbs oil.

After partially falling in the early hours of February 6, the sumaúma (kapok) tree had to be cut back by the city hall. It remains to be seen whether the remainder of the tree, which may be 200 years old, will regrow. Photo: Sandro Barbosa

Regrowth

Considering the significance of the kapok across the Amazon floodplains, it is easy to understand the importance of the fallen tree-person for all the residents of Belém, itself built on a floodplain, though the city has long forgotten its natural origins. On February 9, Kayan Rossi, the director of Urban Green Spaces for the Belém Department of the Environment (Semma), led an inspection of what was left of the CAN kapok. Specialists from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation and the Federal Rural University of the Amazon also took part. Researchers collected samples of the tree to help determine the kapok’s exact age and, more importantly, whether there is any chance of regrowth.

While the fate of this tree-person remains unknown, the other hundreds of trees that make up the landscape of Belém also require care, especially the mango trees that have made the city famous. Planted more than 120 years ago, there is not a single winter when one does not fall. Before the CAN kapok, a mango tree had already toppled in January, thankfully with no human victims. The Semma director explained that the city, in partnership with the Federal Rural University of the Amazon, was in the process of compiling an inventory of Belém’s trees. They have already catalogued the tree-people in the Marco and Fátima neighborhoods and are scheduled to start work this week on the neighborhood of Nazaré, home of the CAN kapok. This inventory will make it possible to assess risks and plan for better management.

“Historically, the way trees have been planted in Belém has been haphazard, with much of it done by residents themselves. This is why the city has little control over its green spaces. Many of the species, including the kapok, and all the mango trees aren’t suited to urban areas. They were planted without soil testing or aerial surveys. That’s why so many of them keep falling. Mango trees, for example, are not suitable for urban afforestation, though no one knew this 120 years ago, when they were first planted. Now we have to deal with the consequences,” Kayan explained. The main problem with the mango trees is that Belém sits on shallow soil, which is not suitable for deep-rooted species. While kapoks are suited to this kind of soil, its soft wood attracts termites. Maybe it is not that the trees were planted in inappropriate locations, but that the city has cemented over the natural world around it.

Semma last inspected the CAN kapok in 2012. A large lesion caused surprisingly by human urine led the city to build a fence around it. People had been urinating on the tree, which opened a wound big enough to fit a person. “It was like an open sore. The injury was treated, and the tree regenerated. From that point on, we considered it to be regenerating. We have been monitoring it and the other three kapoks in the area periodically ever since,” Kayan said.

Because the kapoks are located in a bustling area, where the Our Lady of Nazareth procession takes place, they are also being monitored by the board that oversees this religious celebration’s official events. During the emotional week of the kapok’s fall, a montage accusing the city of Belém of ignoring the board’s request to prune the tree was circulated on social media. In a release sent to SUMAÚMA by the coordinator of the 2023 Our Lady of Nazareth procession, Antônio Salame said that no major problems had been noted in the trees in Praça Santuário or along the procession route, but that every year the board asks the city to examine and prune the tree for the safety of the people in the procession.

Still, despite assurances from all those responsible that everything was done properly, the kapok fell.

Maybe what we should have done in the last 200 years was think about the safety of the tree—and not just the cars, the buildings, the passersby, and the people in the procession. What we should have done was think about how to protect the kapok from humanity.

Translated by Diane Whitty and Julia Sanches