When 45-year-old Rosimar Santos de Oliveira, a Baré Indigenous woman, was raped and killed, allegedly by three men from a different Indigenous community, they all had something in common running through their blood: alcohol. A good part was a gift from the mayor of Barcelos, a city with a population of just under 19,000, nestled on the right bank of the Negro River, in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. Radson “Radinho” Rógerton dos Santos Alves, the winning candidate from the União Brasil party, had promised free beer for everyone who attended his inauguration. He made good on his promise. According to the police, Rosimar and her alleged murderers had been drinking for at least eight hours when the femicide happened. The circumstances of this crime, with its Indigenous victim and perpetrators, were created by the Amazon Rainforest’s invaders. A society that sees itself as “civilized” provided the elements that led to this “barbarity.”

Rosimar spent part of the afternoon and evening of January 1, 2025 drinking at Radinho’s inauguration ceremony. People reported seeing her there after 5:00 PM – at this point, her suspected killers had also arrived, as stated later by witnesses. While Baré’s family had voted for Radinho, it was the promise of free booze that made what was usually a humdrum event into something nobody “could miss.” The Piabódromo, Barcelos’s largest public building, was packed. The horseshoe-shaped arena with cement floors and bleachers, which holds up to 5,000 people, was built to host the Ornamental Fish Festival. It is the city’s biggest event, with music and a dance-off between two teams named after small regional fish in the region, Acará-Disco and Cardinal, in a competition reminiscent of the opposing bulls, Caprichoso and Garantido, at the Parintins Folklore Festival. The mayor refused to provide information on how much alcohol was served and who paid the bill.

A Funai notice (at left) didn’t apply to the mayor: to fill the Piabódromo (center) for his inauguration, Radinho (at left) handed out free beer

The night had already stretched into the early hours of January 2 when an inebriated Rosimar approached a young Yanomami man who was also drunk. Mutually attracted, they went off to be alone. They left the Piabódromo and walked a little over a block to a dark and abandoned one-floor building, which had once been used for years by a phone company. But they were followed.

They had been pursued by three other Yanomami men. These highly intoxicated men all wanted to have sex with Rosimar. When she refused, Klesio Aprueteri Yanomami, 25, Sirrico Aprueteri Yanomami, 19, and O., 17, are said to have held her down, beaten and raped her, before using knives to wound her and then strangle her to death. Part of the crime even made it to video, recorded by cell phone. Rosimar is naked and unconscious – she might already be dead. One of her accused murderers violently manipulates the Indigenous woman’s body, motionless on the grass, before penetrating her. The police say the video – which passed among the city’s residents and to Yanomami villages hundreds of kilometers away – was not made to commemorate the crime, but rather to report it. The Yanomami man shooting the video is heard saying, in his native Yanomam, that the murderers will go unpunished, before he focuses the camera on one of their faces. One of the criminals can also be heard saying, in Yanomam: “Stick it in! Stick it in!”

When SUMAÚMA visited the location nearly one week later, Rosimar’s dried blood could still be seen on the veranda outside the phone company building. A few meters away there was a pile of used rubber gloves and a box of surgical masks, left there by the Amazonas police forensics team.

Blood memory: the veranda of a vacant phone company building holds traces of the violence that took Rosimar’s life

A National Public Security Force team was sent to the area by the federal government because of fears of conflict between the Baré and Yanomami Indigenous peoples. An outcry for punishment grew in the city and – in the most extreme cases – for revenge against the criminals. One suspect was arrested a few days later and taken to Manaus to keep him from being lynched. There was, however, little discussion about what led to the tragedy. In the “civilized” society, a crime is considered to be the sole work of its perpetrators.

Yet this is only partly true. Responsibility spreads far wider..

The napëpë want money

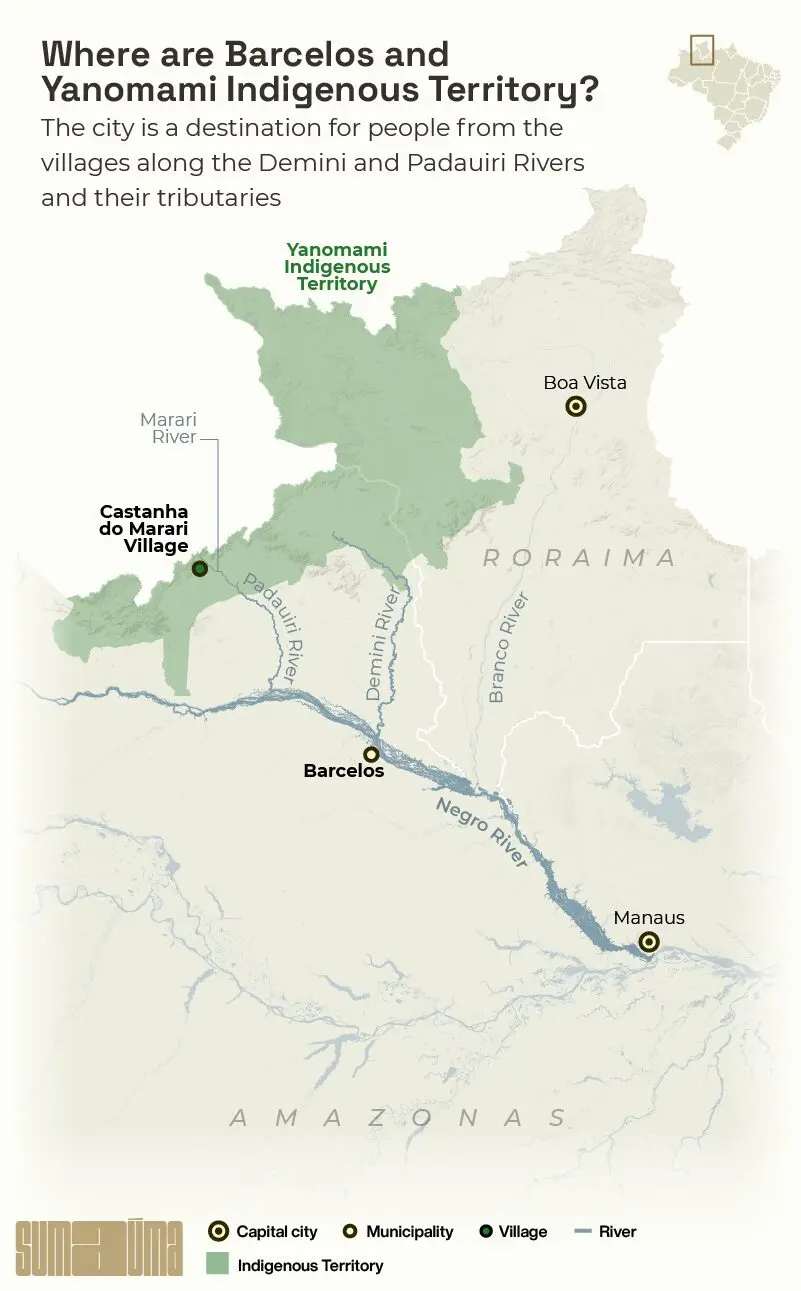

The population of Barcelos was reported as 18,834 people in the 2022 Census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Three out of four residents self-declared as Indigenous. Most are Baré, one of the peoples who first engaged with non-Indigenous people in the 18th century. Yet at Mayor Radinho’s party, there were also many Yanomami, who are forced to go to the city to get their social benefits, like the payments they receive under the federal Bolsa Família aid program, after which they go shopping.

Founded in 1728 by Catholic missionaries, Barcelos was for a time during the colonial period the capital of Amazonas. It is also the second largest municipality in Brazil, in area, stretching from the Negro River, in the south, to the border with Venezuela, in the north. The easiest way to reach the city is by the Negro River: a 12-hour trip from Manaus by express boat, or nearly twice as long on slower vessels. The fastest way to get there is a little over an hour-long flight from the capital, on one of the small chartered planes preferred by recreational fishers. They come from across the country and start their trips upriver in the city during the fishing season, which runs from September to April, with most movement happening in the first three months.

InfogrAPHIC: Ariel Tonglet/SUMAÚMA

The city’s main church, Igreja Nossa Senhora da Conceição, is visible from afar to those arriving on the Negro River. Built in the 18th century, its roof is adorned with a painting of Christ on the crucifix in a tropical forest. Most of the local businesses operate around the church – small shops selling imitation designer clothing, styrofoam boxes, cassava flour, beans, cases of soft drinks, beer, liquor, snacks foods high in sodium and saturated fats, filled cookies, and all types of ultraprocessed food, as well as a range of knickknacks. Surrounded by the lush Amazon Rainforest, Barcelos is poor: per capita GDP – the result of dividing the city’s total production in one year by the number of inhabitants – is a little over R$ 8,800, over five times less than the national average. This is not just one of the lowest numbers in Brazil, but also in Amazonas, where it ranks 57th out of the state’s 62 municipalities.

Poverty is imprinted on the buildings. Even in the city center, many homes have worn paint, their walls are damp with condensation, and their roofs rusted. Its larger and more manicured homes are not at all luxurious: nevertheless, they are surrounded by fences or walls covered with porcelain tiles. The roads are potholed. People mostly get around using low cc motorcycles, which are also used as taxis and even cargo vehicles, hitched to makeshift trailers. They share the narrow main street running parallel to the Negro River with an assortment of cars, bikes, pedestrians, dogs, and vultures.

One week after the crime, we spoke with a woman who owns a business in the city center about Rosimar’s murder. At that time of year, there are few Yanomami in the city – which she said makes her apprehensive for financial reasons. “The Army and the municipal government alone can’t provide enough business here,” she reasoned. She is talking about the 600 members of the 3rd Jungle Infantry Battalion, who live between the barracks and the enclosed and surveilled officer quarters, and the public servants who work at City Hall.

Barcelos’s businesses eagerly await the money that arrives from government assistance and social programs – especially Bolsa Família payments. In December 2024, the program handed out R$ 2.74 million to 3,472 of the city’s families. Of these, 2,246 are Indigenous. And 506 of them are Yanomami families who don’t live in the city, but travel there by the hundreds, every month, to receive payments. According to the Ministry of Development and Social Assistance, Family and Combating Hunger, the Bolsa Família program disbursed R$ 533,000 in funds to Yanomami peoples in Barcelos in January 2025.

The city center in Barcelos, seen from the main church: the city’s poverty is imprinted on crumbling walls and rusty metal roofs

What should be a solution has become a source of new problems. Neither the federal, state or municipal governments care to prepare any type of structure to welcome and advise the Yanomami. The benefits policy was replicated for the Indigenous population with no respect for their completely different way of life and the fact that they are not familiar with urban environments and bank bureaucracies. Many Yanomami do not speak Portuguese, and most understand little of the city and how non-Indigenous people act. Left to their own devices, they become easy targets of the greed and tricks of the napëpë – a term from the Yanomam language which originally meant enemy, but is now used to refer to the white man.

‘I didn’t like Indians before’

Rosimar had a routine whenever she arrived from the small farm she took care of with her partner. She would bathe and go to visit her mother, Idaíde Bernardo Paixão. Whenever possible, she brought cassava flour to make her porridge. At a very advanced age, Idaíde does not see or hear well, but she senses that something bad happened.

“Mother calls for her every day. We lie, tell her she’s not back from the farm. How can we tell her what happened?” Rosimar’s sister, Zuleide Paiva dos Santos, 45, says. Idaíde raised seven daughters. One did not come from her own womb: Rosimar, who was given to her by her biological mother, a Baré Indigenous woman, when she was 7 months old. It never made a difference to either of them.

A hundred years old, Idaíde Bernardo Paixão, her mother, is still unaware of what happened to Rosimar: how can we tell her what happened, one of her daughters asks

Zuleide talks with us on the porch of her home, in the poor community of Mariuá, far from the center of Barcelos. While the porch, with its bare-brick walls, is open, humidity hangs in the air from the sultry early-morning weather. Looking through a window looking into the living room, we can see a campaign sticker for mayoral candidate Radinho.

Zuleide is wearing a shirt with a print of a giant green bottle of beer covered in ice. She sends one of her daughters to fetch Alberto Viana França. He is a thin man whose mouth is stretched into what looks like a melancholy smile turned permanent. He is 54 and met Rosimar almost 20 years ago. December 27, he says without thinking, is the day they married. Rosimar was pretty: she had a round face, as is common among the Baré. Black hair, parted in the middle. A 3×4 cm photograph, the only one the family found of her, shows someone who cared about her appearance, with carefully manicured eyebrows.

“We saw each other and that was it,” Alberto explains, recalling their first date. “We never left each other, not for one day. No fights, none of that.” He looks tired. He says he has barely eaten since learning of the crime. He was given IV fluids at the hospital to prevent dehydration. The evening before, he had started to feel somewhat better – he was able to drink some sugarcane juice. “I miss her so much.”

Alberto insists on showing us the house where he and Rosimar lived with their seven children. It sits behind Zuleide’s house. She shows it to us as soon as we cross two tall thickets that have overgrown what the municipal government calls streets. It is a large home with a few masonry walls and a few wooden walls, whose extreme simplicity is in contrast to the care for detail. The kitchen still has a dirt floor – a wooden platform provides a more solid base for the gas stove. Pans hang from hooks on a wood wall. They are scrupulously organized according to size: bigger pans on top, smaller pans on the bottom. In the couple’s room, which also has a hard and humid dirt floor, a box spring mattress is pushed against the wall and covered by a floral lilac-colored blanket. Alberto sits there to have his picture taken. Two of the couple’s young girls – their youngest is 5, their oldest, 17 – appear. Each of them holds a kitten, just a few days old, in their hands. Beautiful and smiling, they are incapable of comprehending the brutal violence that ripped their mother away from them.

Alberto, her widower, sits on the bed he shared with Rosimar and one of their seven daughters holds a kitten: she is too young to understand the brutality

Alberto and Rosimar planted some crops together nearby. “Cassava, pineapple, banana, yams, sweet potatoes. We’re already harvesting the cassava. And right now when she isn’t here anymore,” he says with sadness. He says he will never, as long as he lives, forget the day his partner disappeared, on the morning of January 2. He wasn’t worried at first: he thought she might be with her dad, Milton Cordovil França, at his house near the Piabódromo. She was not. Then he grew worried. Alberto called a brother who has a motorcycle and they drove around the city looking for Rosimar. They even drove in front of the vacant phone company building a couple of times, never imagining her body was there. “Then I heard they’d found a woman dead. I said – it’s her. I didn’t see the body, but dad did. It was completely broken, cut up by a knife.”

The memory stirs up feelings of anger for Alberto. “Sir, I wish you could have seen all the Yanomami that were here [on the night of the crime]. And how much drugs, cachaça were being consumed. I didn’t like Indians before, now I don’t like them at all,” he spits out. Her father Milton is, like Rosimar, Indigenous Baré. Her sister Zuleide tries to provide some context: “We aren’t mad at all the Yanomami. Nobody knew these ones [suspected of the femicide]. Because the people here in Barcelos [referring to the ones who usually come to the city], they never hurt anyone.”

A bank that floats – but has no money

The Chico Mendes is a large three-story watergoing vessel. It is painted white with light and dark blue accents and boasts a Caixa bank logo. It is a floating bank branch. When it docks in Barcelos, it is impossible not to notice. The visit is highly anticipated: only two banks have branches in the city, Banco do Brasil and Bradesco. For anyone who needs to visit a government-owned Caixa bank, as is the case for Bolsa Família recipients, the periodic arrival of the Chico Mendes Branch, the vessel’s official name, is an event.

The Chico Mendes, a floating Caixa bank branch that periodically docks in Barcelos: the Yanomami don’t believe it doesn’t carry any money. Image: Caixa/press photo

News that the Caixa branch is about to dock spreads through messaging groups and reaches the villages. The Yanomami living near the Demini, Padauiri, Marari, Aracá and Preto Rivers pack into small motorboats and head downstream on trips that can take over a week (the return, upstream, takes longer), heading to Barcelos to pick up their benefits and do some shopping.

The Indigenous population began to receive Bolsa Família payments early in the last decade. Yet the Yanomami, a people whose most frequent contact with the “white world” began between the 1940s and the 1960s, have never been given any type of education on how to deal with money and greed. Indigenous recipients are not required to withdraw their Bolsa Família payments each month. Benefits can accumulate in their account for up to six months. Yet few Yanomami are aware of this.

The Chico Mendes Branch registers people to receive Bolsa Família payments and is where pending bureaucratic matters can be resolved and the cards used to withdraw benefits can be unblocked. It does not, however, let beneficiaries make withdrawals on their payments – for safety reasons, the boats carry no money. The Yanomami are notified of this, but many are simply unable to believe the floating bank has no way to pay them. The alternative for making a withdrawal is the city’s sole lottery retailer. Because it is not a bank, it also does not keep large sums of cash on hand. People hoping to make a withdrawal must instead wait for somebody to show up and gamble or pay a bill for there to be enough cash available. Yanomami families line up by the door for days sometimes, under sun and rain.

When the Chico Mendes docked in Barcelos in August 2024, there were 2,000 Yanomami there, according to someone who works for Funai, Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency, who spoke under the condition she not be named. (The boat returned to the city from January 13 to 15 of this year. But because of fears following Rosimar’s femicide, few Yanomami were there waiting for it this time.) And the more of them in the city, the easier life is for the napëpë who work to trick them and take their money.

Minôrio (at right, no shirt) and his family get ready to go shopping: the Yanomami’s Bolsa Família payments inject over half a million Brazilian reals into Barcelos’s economy each month

“The Yanomami gained economic independence with the benefits. But it is a population that has had a very initial access to education programs, that is totally unaware of basic math,” according to Marcelo Moura, who holds a master’s and a PhD in social anthropology from the National Museum, an institute connected to the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “Throughout the process, they will fulfill obligations, like accessing civil records, without understanding any of what they’re doing; they will access money without much understanding of where it came from, or why it is distributed,” Moura says. He spent 20 months during a five-year period living in Yanomami communities around the Demini River while doing anthropological research in the area.

When the city is packed as it was last August, it is normal to see drunken Yanomami – almost always men – in the street. Alcohol is not something the “white man” introduced into Indigenous life. In one text from a collection published by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), entitled “Alcohol Abuse among Indigenous Peoples in Brazil: a Comparative Analysis,” American anthropologist Esther Jean Langdon notes the original peoples of the Americas have always prepared fermented drinks for consumption in traditional rituals and even at parties held to have fun with drunkenness. Yet this changed.

Outsiders have brought in much more potent liquor. And now there is a seeminglyinfinite supply of alcoholic drinks in bars and markets.

“Before Indigenous societies were dominated by European civilization, the use of traditional fermented beverages was marked by control and sociocultural limits, which is no longer the case with most South American Indigenous peoples,” writes the anthropologist Langdon, who has dedicated her life to researching topics like Indigenous shamanic cosmology, Indigenous relations with the State, and health policies. Citing the Bororo, a people who traditionally occupied a territory extending from western Bolivia to the south of the present-day Brazilian state of Goiás, Langdon notes they “used to prepare chicha [a fermented drink made from corn, cassava or fruit] to get happy. The behavior of those who now drink cachaça is, to the contrary, characterized by aggression and physical violence.” She continues: “If historically the use of alcoholic drinks made a positive contribution to Indigenous peoples, its consumption today has strayed from the traditional style. Indians (sic) are drinking other substances and they often do this in new social contexts. These changes have highly negative consequences for the communities, in the form of general and family violence, malnutrition, harm to children’s health (in cases of fetal alcohol syndrome), people being run over on roads, etc.”

At the Funai post in Barcelos, a sign right at the entrance notes that according to a 1973 law known as the Indian Statute, which is still in effect, it is a crime, punishable by arrest, “to allow, by any means, the acquisition, use, and dissemination of alcoholic beverages” among the original peoples. The warning is ignored, even by the city’s mayor. “Offering alcohol is a strategy of cooption, of vulnerabilization [of the Indigenous peoples],” Moura says. “We heard a lot that the Yanomami will vote [for a certain candidate] because they hold parties, provide drinks, give [them] things.”

Inebriated, the Yanomami even fight each other in the street. It is not uncommon for them to come out injured. They also become easy prey for traffickers of drugs like crack and cocaine, which are easy to find in Barcelos. Seduced by the city’s drugs, but far from their villages, they look for intoxication wherever they find it. According to members of the city’s Indigenous association, in Castanha do Marari Village, where they live, the men suspected of raping and murdering Rosimar would get high by huffing the gas used to fuel motorboats.

According to the Yanomami ways of war, women are never killed. The barbarity against Rosimar is not characteristic of their people’s culture. Nor is extreme intoxication.

A Yanomami at a camp on Praia Grande Island, in Barcelos: Indigenous people are ill at ease in the city, preferring to keep some distance from the ‘napëpë’

‘Is oral sex real?’

The internet is still something new to the Yanomami. High-speed satellite internet from Starlink antennas, made by the company belonging to the newest member of Trump’s inner circle, Elon Musk, were probably first brought to the territory by illegal miners.. Starting in at least 2023, non-governmental organizations began to install them near health posts in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, to ensure that leaders can pass along notifications of health emergencies and invasions of their territory. These NGOs are careful to block access to pornography and gambling websites. It is of little use.

In Yanomami villages, mobile phones and portable and powerful speakers are nowhave become considered as basic needs. In Barcelos, SUMAÚMA heard reports of how this novelty fascinates people. The internet and electricity top lists of requests made to government organizations and agents. Indigenous people who work with mining in any way prefer to be paid in cell phones and tablets rather than receiving money. It is something you see on the city’s streets: in each group of Yanomami we ran into, there was someone with their face immersed in a cell phone. The devices are the most in-demand items among Indigenous people at local businesses. “They buy them and buy a lot, friend,” one salesperson at a store in the city said. During times of great influxes of Yanomami, inventories can even run dry due to demand.

Kwai, a Chinese social media platform for sharing short videos and a sponsor of Big Brother Brasil whose slogan is “Make Everyone Shine,” is extremely popular with the Yanomami. Moderation on the network is unreliable and it is being investigated for sponsoring the spread of lies about vaccines and elections. It is also infested with sexual content, including content involving children and adolescents. One quick internet search brings up profiles with names like “adults only” or “hot girls of Kwai.” This exposure to pornography changes how the Yanomami deal with sex. One NGO employee, who asked to remain anonymous, says she was approached by a young Yanomami who showed her a video of a woman practicing oral sex on her partner. “They want to know if that’s real, because it’s something that doesn’t exist in their culture.”

In the center of Barcelos, a Yanomami woman finds entertainment in her cell phone: the device has become a basic need in the villages

Architect and anthropologist Daniel Jabra works at the Pro-Yanomami and Ye’kwana Network in Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, a city near Barcelos, and is aware of the problem. “Today’s young Yanomami adults don’t participate in a process of schooling and political education within the Yanomami’s own view,” he says. “Since 2015, we’ve started to see destructuring of Indigenous school projects. They serve as a microcosm of the white world, which raises awareness of the evils of our world. Yet many have grown up without having had this opportunity.”

The circulation of content among the Indigenous doesn’t even depend on the internet’s existence. Apps like Share It let them exchange videos directly between devices. “Whoever goes to the city or to somewhere with internet comes back loaded with new things, and soon the videos are on all of the community’s cell phones. Everything arrives at a surprising speed,” says the NGO employee. The problem has become so serious that it has been put on the agenda at events held by Yanomami organizations. Last August, a meeting of young Marauiá River Yanomami, supported by the Hutukara Yanomami Association, which is run by shaman Davi Kopenawa and by the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, put “excessive cell phone use and gambling” and “use and circulation of pornography” on its list of “current problems in relation to young people,” alongside “drug and alcohol use” and “excessive consumption of industrialized food.” None of this is from the traditional Yanomami culture. It is a napëpë thing.

‘The worst of our world’

Their importance to the local economy is not reflected in the spaces reserved for the Yanomami in Barcelos. They can normally be found camping on beaches along the banks of the Negro River or in distant areas on the city’s outskirts. The city is already poor and precarious for the vast majority of its residents. It nevertheless saves the worst of itself for the Indigenous visitors whose money it does all it can to take.

A child at a Yanomami camp on Praia Grande Island, in Barcelos: the city saves its worst for the Indigenous people

“When I went to live with the Yanomami, I was welcomed very warmly. And I always think about how we welcome them in our world,” Marcelo Moura says. “They can’t even access consumption with full dignity. We only offer the worst of our world: low-quality food, drugs, alcohol, prostitution.”

It’s as if the two worlds, the Yanomami’s and the napëpë’s, only touched at the edges. In their case, the “edge furthest from the living standards and organization of society, with the Indigenous vulnerable because they lack social protection, finding the edge of our world, sleeping in the street, in unhealthy locations, with no knowledge of how to access citizenship, with no explanation in their own language of what the social programs are,” the anthropologist says. “And then they’ll say that all the city has is thieves, is drinking, because that’s all they see.”

It is easy to recognize the Yanomami in Barcelos – even from far away. Thin and small, they move in large groups. Whole families normally travel together to pick up their benefits and go shopping. Minôrio Yanomami took his wife and two kids, along with other relatives, on a four-day trip down the Demini. On the first day we saw them, in the city’s commercial district, he expressed mistrust, he misunderstood us, he struggled to speak Portuguese.

One day later, we ran into Minôrio and his family again. This time, on Praia Grande Island, which sits in front of Barcelos and is usually filled with locals and some tourists on weekends. The Yanomami don’t stay in the main beach area, but in a small clearing along the banks of the Negro River, separated by a few dozen meters of thick woods. It is a thin strip of sand studded with the wooden stakes they use to hang their hammocks. Spread across the ground are empty plastic bottles, wrappers from snack foods and filled cookies, and instant noodle packages. (Another camp, on a neighboring island, also had a pile of empty beer cans.)

The worst of the white world: the trash from a Yanomami campsite, in Barcelos, contains beer cans, soft drink bottles, and empty snack packages

The presence of health agents who work with the Yanomami makes Minôrio feel more at ease to speak. “Staying here is safer. The city is dangerous,” he says, mentioning their fear of being attacked by residents after the crime. “If I didn’t have to come, I wouldn’t have.” Minôrio says he has previously waited 15 days for the lottery retailer in Barcelos to finally have money for him to withdraw his benefits.

It is a precariousness welcomed by the people who want to cheat the Yanomami: SUMAÚMA heard reports of vendors and actors who, claiming they want to help the Indigenous people, give them goods at no charge, but in exchange keep their benefits cards and PINs. One Funai worker even once mistakenly received an audio message, in which a woman from Barcelos admitted she was holding on to the benefits card of at least one Yanomami person, a man named Marquinhos, because of a debt. When asked by Funai, she refused to hand it over. Police are familiar with the scam. “It’s a practice that does happen in the interior of Amazonas. In Barcelos, since there isn’t even a Caixa bank branch, the card and PIN become a sort of collateral,” says the city’s police chief, John Castilho.

A lack of police reports filed by victims makes looking into it difficult, but the city’s police do have one ongoing inquiry: three vendors are being investigated for these practices, which at a minimum constitute criminal fraud. In Santa Isabel do Rio Negro, a city near Barcelos, one vendor was arrested for embezzling R$ 80,000 from benefits cards.

A hazy entity

The Xoromawé Indigenous Association was founded a little over three years ago. Its members are mostly Yanomami living near the Padauiri River and its Marari tributary, in western Yanomami Indigenous Territory, where Castanha do Marari Village is located. It is led by Geraldo Aprueteri Yanomami – who, coincidentally, is a stepbrother to Alberto Viana França, Rosimar’s widower. Day-to-day operations are run, however, by the vice president, Rui Leno Macedo de Moraes, who is assisted by his wife, Ana Lacerda, the organization’s first secretary. Both identify as Baré Indigenous people. It is Rui Leno’s signature, and not Geraldo’s, that validates the association’s official documents.

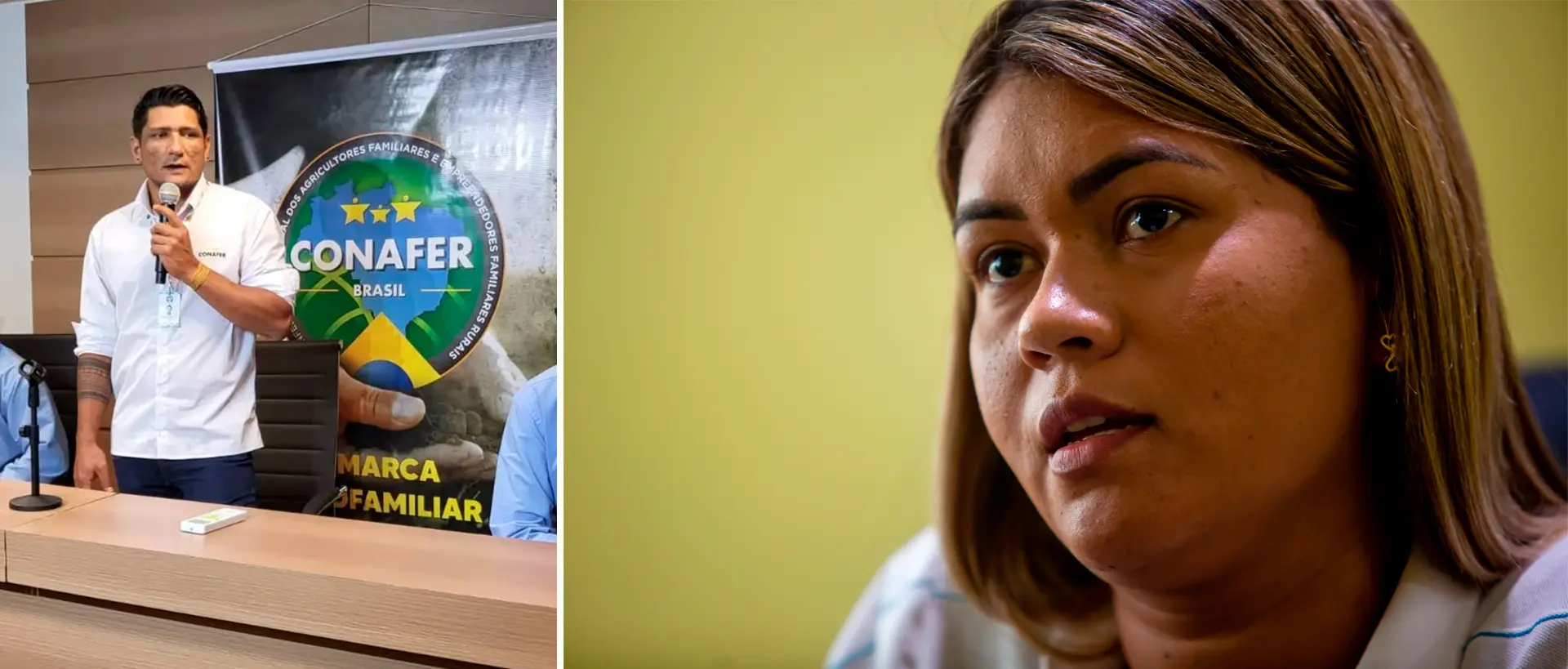

The story behind Xoromawé is entangled with the arrival of another organization in Barcelos that has been encroaching on Indigenous Territories: the National Confederation of Family Farmers and Rural Family Entrepreneurs, which is better known by its acronym, Conafer. According to its website, Conafer was “founded in 2011 based on the need for Brazil’s family farmers to have an autonomous voice in decisions related to the country’s agricultural sector.” It has offices in Brasília and is led by Carlos Lopes, who introduces himself as a Tapuio Indigenous man. “They support 244 peoples,” Rui Leno says. “I praise God for the life of our president,” who is treated as the “godfather of Xoromawé.”

Rui Leno, of the Xoromawé Association: connected to Conafer, the Association is suspected of illegally withholding money from Indigenous benefits

On top of the desk where we are asked to sit at Xoromawé is a pile of applications for Indigenous memberships to Conafer. The forms even ask if the applicant has a bank account, which is not necessary to receive Bolsa Família payments, for instance. “Here we only do memberships for Xoromawé,” Ana explains. “But we offer benefits to anyone who joins Conafer,” she adds, admitting to the confusion between the two.

The two entities are regarded with reservations and kept at somewhat of a distance by more traditional Yanomami organizations, like Hutukara. For them, Xoromawé and Conafer encourage the Yanomami’s disorderly descent to Barcelos to pick up benefits like Bolsa Família – placing the Indigenous people in a vulnerable situation and, at the limit, resulting in crimes like the femicide of Rosimar. “Since Xoromawé started, this has been their main front of work,” says anthropologist Marcelo Moura.

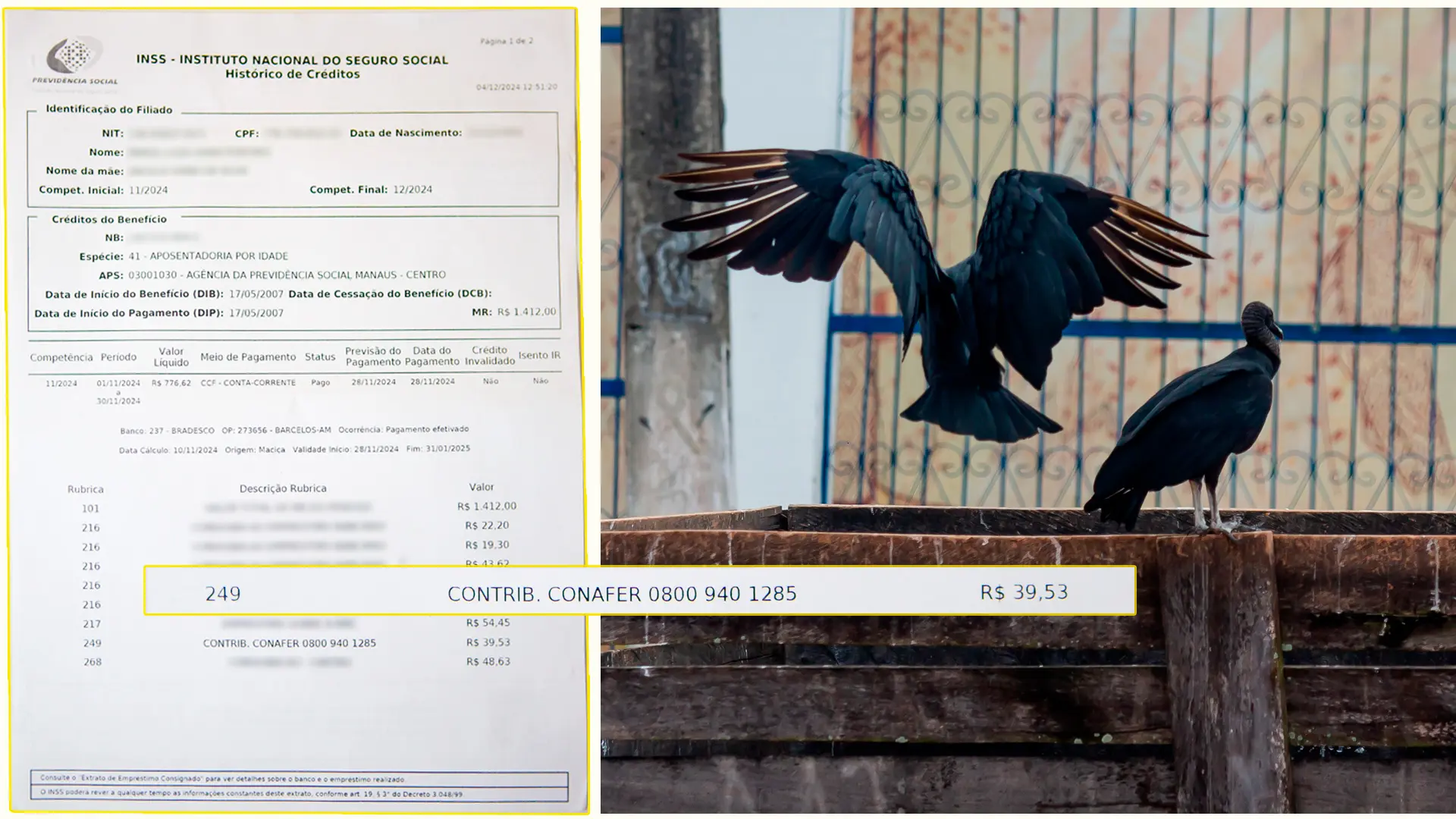

Xoromawé and Conafer say they do not charge any kind of monthly dues to Indigenous members. Yet SUMAÚMA received a document that showed R$ 39.53 was deducted from a pension payment to a Baré Indigenous resident of Barcelos, which was itemized as “Conafer contribution.” When asked, the entity said this was a “pension deduction levied so the retiree would have access to various Conafer services,” which is not mandatory and can be canceled at any time.

The Baré woman to whose pension payment was deducted is illiterate. The misappropriation was only noticed by the family when their mother’s name was placed on a debtor registry because of the debt incurred by this deduction. “We didn’t know. She was never notified,” said her son, who asked to remain anonymous. “Deductions are also taken from my siblings, and none of them are retired,” he responded when told of Conafer’s response.

A social security document showing money discounted for a payment to Conafer, taken out of an Indigenous woman’s pension: her family says it was not authorized

When confronted about the Conafer charges, Rui Leno said: “You all come here and take advantage of everyone’s weakness to make a tempest in a teapot. What we want is justice for Rosimar, for the crime to be investigated. I am receiving death threats from the Indigenous Baré population. And from the Yanomami too. I’m in the crossfire.”

Conafer’s influence on the city can be measured electorally. Natalia de Souza da Silva, who worked collecting memberships for the entity alongside Rui Leno, was elected to the city council last year. In an initial conversation with SUMAÚMA at her office, she confirmed she had worked at Conafer. Later, when asked by message if she informed Indigenous people that their membership could have a cost, she declined to answer. “I recommend, sir, speaking with Conafer in Brasília to ask whatever questions you want,” she said.

The national secretary of Policies for Monitoring and Security at Conafer is an Indigenous man, Geovanio Oitaiã Pantoja Katukina. He served under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) as a coordinator of Isolated and Recently Contacted Indians at the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai – a position once held by Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira, who was murdered in Vale do Javari in June 2022 along with British journalist Dom Phillips. In December 2022, Geovanio Katukina was the target of a Federal Police operation. He was suspected of hindering protection of isolated Indigenous peoples in the Ituna/Itatá Indigenous Territory, in the state of Pará. Targeted by land grabbers, Ituna/Itatá was at one time the most deforested Indigenous Territory in Brazil. Geovanio Katukina issued a report questioning the presence of isolated Indigenous peoples in the area – a theory embraced immediately by land grabbers and those defending them. Through his press office, Katukina said that “it is inappropriate, at this time, to show proof or go into details about the suit, since these matters should be decided by the courts,” and that “the Constitution protects all citizens from incrimination prior to a definitive ruling.” He also added that “I am confident that I am not involved in any irregularity.”

A little over 20 days after the crime, Xoromawé launched a crowdfunding campaign online with the goal of raising R$ 20,000 for Rosimar’s family. The association will collect the money. According to Rui Leno, the full amount collected will go to her widower, Alberto. He added that he asked for help from “Senator Damares [Alves, of the Republicanos, representing the Federal District, and a former minister under the Bolsonaro administration] and Senator Plínio Valério [of the Social Democratic Party, representing Amazonas, who is a Bolsonaro-backer known for opposing the work of environmentalist NGOs working in the Amazon]” when announcing the effort. Alberto is seen asking for help in a campaign video: he says he is unable to work his farm or fish because he has to care for his children, some of whom are very young. In an audio message sent to a WhatsApp group of people from all over Barcelos, one of Rosimar’s nieces complains about shots being used in the video of Rosimar and Alberto’s children – all are minors. Yet other family members say their father authorized publication of the material. As of the afternoon of January 24th, only R$ 530 had been donated.

SUMAÚMA tried, unsuccessfully, to contact Geraldo Yanomami by cell phone.

At Funai, Geovanio Katukina (left) made decisions against Indigenous people. Now he is at Conafer, which got Natalia Souza (right) elected to the city council. Screenshot from Instagram

‘The Indigenous woman’s body is very sexualized’

The main square in the center of Barcelos slowly fills with people – mostly women – on a late Thursday afternoon in January. They are there to do some ritbox, an activity held outdoors weekly that is a mix of exercise and dancing. We talk to two of them, who say they are social workers. We ask about Rosimar’s femicide. After a few minutes, they begin to tell us what it is like to be a woman in the seemingly peaceful and quiet Barcelos. The New Year’s Eve crime made an already daily fear even more acute.

“I arrived by boat at night and I only felt safe because someone I know came to pick me up,” one of them says. Because they are scared, neither want their names in print. During the pandemic, they say, motorcycle taxi drivers committed three rapes in just nine months. “Our bodies don’t belong to us. The Amazonian woman’s body is seen as score-able. The Indigenous woman’s body is very sexualized. I’ve seen lots of 13-year-old girls with men over 30. Always with the argument that the family allowed it, that the girl knows what she wants from life,” the friend says. Two days after the murder of the Baré Indigenous woman Rosimar, there was another rape in the city, this time a Yanomami woman – the suspect is also Indigenous and had been drinking, according to the police.

They are crimes, they believe, which are likely to make the city more prejudiced against the Yanomami. The Saturday before, the first after the crime, a protest against it ended in shouts of “Get out, Yanomami.” The federal government sent the National Public Security Force to Barcelos to “pacify and preserve public order in light of the tense situation involving the Yanomami and Baré ethnicities,” according to the Justice and Public Security Ministry.

At a protest in Barcelos people shouted ‘Get out, Yanomami.’ The suspect arrested was taken to Manaus, for reasons of safety. Photos: Guilherme Gnipper and Erlon Rodrigues /PC-AM

Sirrico Aprueteri Yanomami, one of the men suspected of committing the crimes of “rape, femicide, and desecration of a corpse,” was arrested and taken to Manaus. The other two, Klesio Aprueteri Yanomami and a minor, fled by boat to Castanha do Marari Village. The chief of police, John Castilho, said he received a video where they said they were willing to resist. “The situation is extremely delicate. This arrest is not just a police matter,” he explains. Funai employees should visit the village to speak with the suspects and try to negotiate their surrender. If they do not turn themselves in, an explosion of dissatisfaction could blow up against a Yanomami person who has nothing to do with the crime. Along with the police station, Barcelos has nine military police officers, who alternate shifts with the help of six municipal guards and who have just two police vehicles.

Mayor Radinho is an aquacultural engineer born in Manaus four decades ago. He was an Amazonas government worker for years and had never previously won an election in his life. SUMAÚMA tried contacting him at his office and by phone. He was initially willing to answer our questions. However, once we sent them to him, he stopped answering our phone calls and text messages.

“We want justice. But this is in the hands of the police,” Rosimar’s sister, Zuleide, says. “And I hope they take measures, because what happened to her could happen to other women walking around out there.” While they try to comprehend and deal with the brutality, her family members harbor a grudge. Radinho, the politician behind the party that was decisive in the tragedy that changed their lives forever, has never visited them to express his condolences. He hasn’t even bothered to send a text message.

The Piabódromo is set to fill from January 30 to February 2, during the 2025 edition of the Ornamental Fish Festival of Barcelos. The Acará-Disco and Cardinal teams will dance, there will be shows with sertanejo, forró and piseiro music, as well as a special final concert by Pixote, a pagode band from São Paulo. The mayor will be there with the 3,000 tourists who are expected to attend. The alcohol will flow. There is no homage planned for Rosimar, whose death began at a party held in this same spot. For the mayor, tourism and local businesses, it is best for the crime to be quickly forgotten.

Everyday threat: in Barcelos, as across the entire Amazon, rapes are commonplace and women are afraid to walk down the street

Editing: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum