These days, few things affect retired 62-year-old doctor Cláudio Esteves’s mood or get him worked up. But just say the word Yanomami during a conversation and his eyes light up, he raises his voice, the messages he types out on his mobile phone spread at a frenetic pace. His emotional bond with this group of Indigenous people, the result of having lived with them for fifteen years, has clearly left deep marks. Not even having to draw on his social security retirement benefits early, in 2017, due to serious heart disease, and not even the emotional shocks caused by the political persecution he suffered over twenty years have stopped the doctor from continuing to be a staunch defender of the Yanomami and the Ye’kwana who live in the Brazilian Amazon.

When he decided to practice medicine in Yanomami Indigenous Territory in the early 1990s, Cláudio witnessed illegal mining’s devastating control of the area, with the Brazilian press reporting the presence of approximately 40,000 illegal miners. In the fifteen years he lived there, he watched the territory’s destruction grow as well as the rapid spread of disease among Indigenous people. Along with his spouse Deise Alves, also a doctor, Cláudio implemented a revolutionary public health method, first on the Pro-Yanomami Commission (CCPY) and years later at the helm of Urihi-Saúde Yanomami, a non-governmental organization (NGO) the story of which was told by SUMAÚMA in 2023.

With the approval from the Ministry of Health, Urihi worked to lower the incidence of malaria by 99% in the time the NGO was active [1999-2004]. According to epidemiological bulletins issued by Brazil’s National Health Foundation, no deaths from malaria were reported from 2001 to 2004 in the villages served by Urihi. Infant mortality fell by 65%. Tuberculosis began to be diagnosed and treated in Indigenous villages, whenever possible. Vaccination of Yanomami children followed the Ministry of Health calendar. There were no cases of malnutrition.

Cláudio and Deise’s work was always an obstacle for illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory and it created a political nuisance. Because they did not agree to interference by political oligarchies in health, those same authorities chose to terminate Urihi’s agreement with the federal government some years later. In the end, they became victims of government bureaucracy who were sentenced to repay the government for not proving that public money was used in Urihi’s agreements. They never filed a legal appeal – this was first due to naiveté and because they didn’t believe that questions asked by the Federal Accounting Court, which they found to be impertinent, would have real consequences; later, it was because it was financially impossible to pay for attorneys.

Now, in the face of the persistent health and humanitarian crisis in Yanomami Territory, the reserved and disillusioned physician felt the need to stir once more. In this interview with SUMAÚMA, where he asked for responses to be provided in writing because of health problems, Cláudio criticizes the Lula administration’s failure to prevent the Yanomami genocide. “The government’s action against illegal mining was more propaganda than effective fighting. And then, once the dust settles on the international scandal, the government and security forces forget about it.”

The 308 Yanomami deaths between January and November 2023 could have been prevented, he says. “Yes, the Yanomami can be saved. But the government has already wasted a year.”

Below are the highlights of our interview, where he draws from his professional experience with the most successful health intervention in Yanomami Indigenous Territory to point out the biggest mistakes made in operations carried out by the federal government.

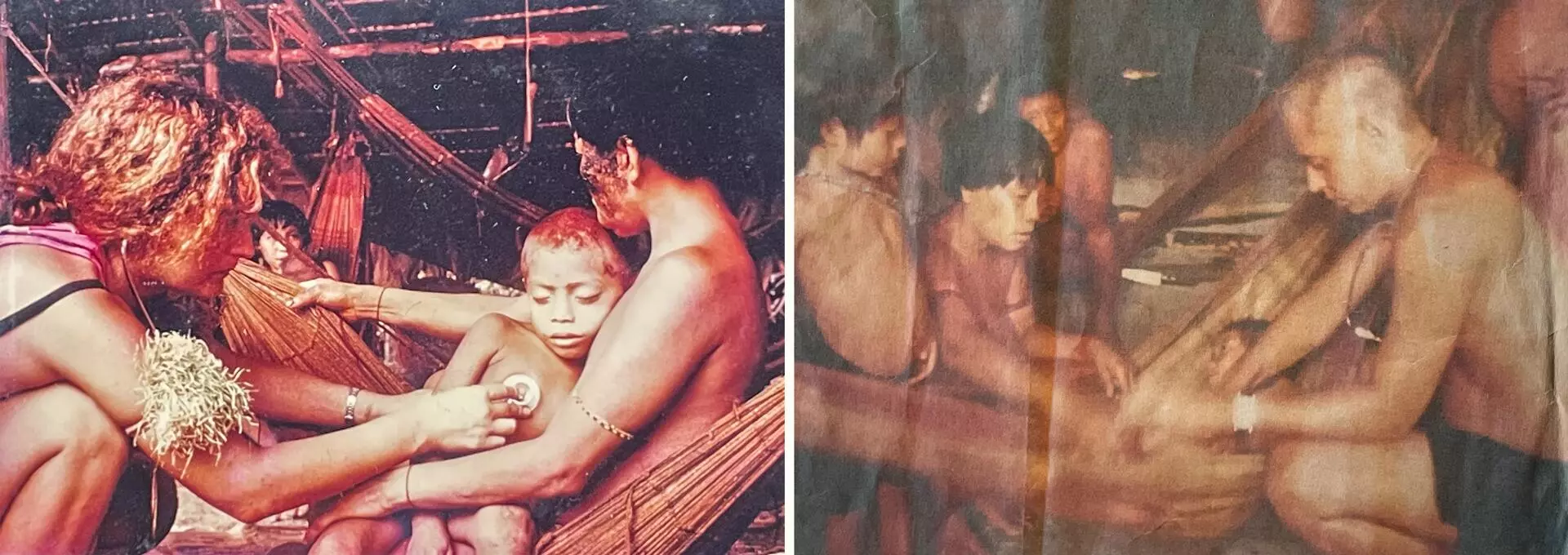

The work the doctors did in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory brought deaths down to zero: Deise (at left), in 1993; and Cláudio, in 1998. Photos: personal archive/authorship unknown/reproduction: Brenda Alcântara/SUMAÚMA

SUMAÚMA: In early 2023, when you and Deise told SUMAÚMA the story of Urihi, you both showed a mix of hope and fear for the future of the Yanomami. You feared that the task force assembled by the Lula administration was incapable of resolving the countless public health problems in the area. One year later, your diagnosis has been confirmed. What happened, in your assessment?

Cláudio Esteves de Oliveira: The health of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana basically depends on resolving two problems: the presence of illegal mining and the structure of the Yanomami Special Indigenous Health District, in particular the direct contracting of human resources by the government. In February 2023, we believed the government would eliminate illegal mining in the Yanomami-Ye’kwana Indigenous Territory and would maintain permanent surveillance. It had all the resources [to do so]. The truth is that none of this happened.

Getting rid of illegal mining is no easy task, but it’s also hard for the criminals to keep illegal mining going in Indigenous Territory. You need quite complicated logistical support. If getting rid of illegal mining and maintaining surveillance to repress new operations was possible in the first big wave of invasions by illegal miners in the late 1980s, today, with many more financial and technical resources, nothing justifies active illegal mining, at full bore, one year into the Lula administration.

In 2023, we were somewhat optimistic about resolving these two problems. [Yet] staff continue to be hired in a makeshift manner and illegal mining continues to operate with total freedom. Hence the continued humanitarian tragedy.

By November 2023, 308 Yanomami had died, often because of health problems and treatable illnesses, such as malnutrition, diarrhea, malaria, and pneumonia. Over half were children. Where is this administration going wrong?

The extremely negative effect of illegal mining must be recognized, today in association with international organized crime, which moreover prevents some regions from receiving care. Yet there is also a long-standing structural problem, which is the way that human resources are contracted. [The NGO] Urihi-Saúde Yanomami was founded [in 1999] and entered into an agreement with the National Foundation of Health (Funasa), based on the experience of the CCPY (the Pro-Yanomami Commission), on a lesser scale, with the intent to create a care model to be transferred to the State. To our disappointment, since the start of the first Lula administration, the Regional Coordination Office of Roraima’s Funasa has been divided into political parcels. Funasa then reformed Indigenous health, which basically reduced agreement-holders to the role of third-party staff contractors. So we decided, in 2004, not to renew the agreement, despite Funasa’s own insistence, from Brasília. At the time, Alexandre Padilha [a public health physician who is currently the Minister of International Relations] was the director of the agency’s Indigenous Health Department. What came later, as everyone knows, was generalized corruption and a gradual degradation in care in the Yanomami Special Health District.

In addition to maintaining the agreements system, today’s salaries are low and, therefore, not at all attractive for work in the conditions of the Yanomami-Ye’kwana Health District. Although the district currently has over 1,000 employees, including non-Indigenous and Indigenous health agents, these health professionals are not acting effectively [a November 2023 bulletin from the Yanomami Emergency Operation Center said that there were 1,850 employees working in the territory and at the Indigenous Health House].

Specific education of licensed practical nurses and Indigenous health agents, who are at the base of care through telemedicine, considering the spread of this population across this large territory, practically no longer exists. Many of the non-Indigenous workers are on medical leave, and of those entering the area, there are few who go to the villages. They stay at the Base-Centers, with rare and heroic exceptions. In addition, the Health Emergency Center of Operations (COE), under the Ministry of Health, rejects the expertise of health organizations, like Doctors without Borders (MSF).

Urihi fought the malaria epidemic in Yanomami territory in an exemplary way. Today, there are around 2,000 cases of malaria per month, a higher rate than under the previous administration. As a doctor, you have always drawn attention to the fact that temporary teams that do not stay in the villages are unable to resolve the problem. Why are care and epidemiological surveillance so lacking?

Mostly because of the nefarious effect of narco-miners, who not only prevent care in some regions, but also make huge craters in riverbeds that are then conducive to breeding the mosquito that transmits malaria, the anophele. Yet even in areas where health teams can work, there are few villages with permanent care. What is known as an active search for cases within villages, done continuously, is essential.

Is it possible to eradicate malaria in Yanomami Indigenous Territory? What did you do at Urihi that could be replicated now?

Regarding malaria, patients do not need to be isolated. The main strategy [at Urihi] was to have a permanent licensed practical nurse or Indigenous health agent, with a microscopist, in all of the villages, to diagnose and treat all of the cases. We would rotate the teams for breaks. This [was done] with the support of telemedicine for serious cases, not just of malaria, but also for other diseases.

The doctor, remotely or occasionally on-site, when possible, cared for these serious or more complex cases and would decide whether the patient could be treated in the area or if they should be evacuated. That was what we did during the hyperendemic phase (when there was high incidence of the disease). When malaria cases were practically at zero [in 2002], the teams began to make regularly scheduled visits or to answer Indigenous requests for an on-site check of a given health problem that had emerged in the time between visits.

Another key point in care for the Yanomami: there was permanent social control, not just in meetings of the District Health Council. Those who did not follow the health care model, employees that didn’t go to the villages, for instance, were reported by the Yanomami-Ye’kwana and were immediately fired by Urihi.

Urinhi served around 11,250 Indigenous people at the time, in a territory where approximately 15,000 Yanomami lived. Of course now the population has risen [exceeding 31,000 Yanomami]. It’s become a bit more complicated.

Half of Yanomami deaths in 2023 were children. Are medical evacuations best for treatment? What special medical care should have been provided to malnourished children who have malaria?

Medical evacuation is done as a last resort. Usually the entire family is evacuated. And when it is prolonged, the family misses the period in the year when the planting needs to be done, and they return to the area to go hungry again. Doctors Without Borders wanted to help with field teams, handing out food packets, which is a very effective method. But the Yanomami Public Health Emergency Center of Operations (COE) rejected this idea. Perhaps now there is an opportunity to again attempt a partnership with Doctors Without Borders for area treatment of cases of child malnutrition. They have had many successful experiences and use these packets, with food preparations that are very appropriate for moderate to severe cases of malnutrition. In these situations, the digestive tract’s ability to absorb [food] is also affected. It’s not just any regular food that helps in treatment. The packets have to be authorized by Brazil’s health regulator, Anvisa.

An important detail: the people taking care of the logistics always need to have cargo ready, to take advantage of any medivac flights for serious cases. [They have] to know the geographical distribution of runways and flight times. It’s not that complex. The person planning logistics has to think as if the money were coming out of their own pocket. The logistical side has to know the amount of all of the supplies, of each Base-Center, in real time, to take advantage of unplanned flights. Deise took care of all of this, to optimize transport.

The goal is to pass along some accumulated knowledge and get the next generation excited. Of course it’s possible to do all of this, and it’s even better [to do it]. Of course it’s possible to end illegal mining, of course it’s possible to end malaria. Of course the Yanomami will return to their traditional subsistence activities, despite some getting lost along the way. And today there are many more resources than before for the Yanomami Special Indigenous Health District. But first we need to cross some deserts.

The Lula administration has set up a task force to combat diseases and illegal mining in the Indigenous Territory and has declared a health emergency of national importance. You and your CCPY colleagues are part of an old guard group that knows the Yanomami territory better than anyone else. Was anybody in this group called to talk about the situation and provide opinions on how to help fight the tragedy in the Indigenous Territory?

Never. Arrogance is the mother of ignorance. Dr. Deise Alves Francisco and I had the privilege of the support of the CCPY group, especially of anthropologist Alcida Rita Ramos, of anthropologist Bruce Albert, and of Brother Carlo Zacquini, of the Catholic Church, one of the pioneers in knowledge on the Yanomami, back in the 1960s. They opened the doors to the world of the Yanomami and the Ye’kwana for us. But it’s not just Deise and I. Later, Urihi formed a fantastic team, in health and education. There was a lot of accumulated experience, from many people, that was eschewed.

When telling the story of Urihi, you and Deise say political interests destroyed a successful public health project in Yanomami territory from 1999 to 2004. The political parceling of the Funasa, during the Lula administration’s first term, was supposedly behind this. Do you think this situation is being repeated now? The current administration promised to get rid of the Funasa, but backed down due to pressure from the “Centrão” [a powerful coalition of self-interested conservative politicians].

Well, it’s a different context. Today there is the Office of the Secretary of Indigenous Health (Sesai), under the Ministry of Health. This Office was a long-standing demand that originated in Roraima, precisely because we noticed the agreements’ vulnerability from the start [of Urihi’s operations]. Indigenous health was freed from Funasa’s grip and from its political parceling, the worst there is. But after a year, the Sesai wasn’t able to structure the Indigenous Health Districts and take over human resources management. Despite the fiasco, I still support self-management of Indigenous peoples whenever possible. But the current administrators, the Sesai as well as the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai) and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, are not managing to achieve good results.

What would Dr. Cláudio Esteves do differently in the current tragic scenario? What ideas and solutions could help the government to confront this situation in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory? Would you be willing to go back and point out some solutions? Why does this topic stir and move you so much, despite having been persecuted and punished by the government for years?

The wheel doesn’t need to be reinvented: illegal mining has to be expelled and permanent care has to be provided in all of the villages. Concerning a return to Indigenous Territory, even as a volunteer (I’m retired due to disability), it would be impossible now, for family and health reasons. But if anyone wants to talk to me, I’m always available. My emotional bond is with the Yanomami and the Ye’kwana. The government and presidential administrations have nothing to do with this. To my and Deise’s surprise, the destruction of the Yanomami Special Indigenous Health District and Urihi’s persecution began at the start of the first Lula administration. Let’s hope that the third Lula administration is different. The first year was not encouraging at all.

Does this emergency task force assembled by the government in 2023 lack knowledge about the reality of the Yanomami people?

Yes, they are completely unprepared. But it’s not just a lack of knowledge. To make matters worse, the government’s action against illegal mining, in early 2023, was more propaganda than an effective fight. And then, once the dust settles on the international scandal, the government and security forces forget about it.

Was the Lula administration under the Army’s influence in the operations in Yanomami Indigenous Territory? Would this be one of the obstacles? Or is it impossible to operate in the territory without the support of the Armed Forces?

If they were under its influence, it was a serious sign of weakness. The government’s cowardice is proportional to the power and autonomy of the Armed Forces. The Armed Forces have a constitutional duty in the Amazon. And they obey the civil authority, in this case the Ministry of Defense. After that bombastic start in 2023, where the government said that it would spare no effort to remove illegal miners and turn around the humanitarian tragedy of the Yanomami, they spent a mountain of cash and the result was negligible. After waiting some time for concrete results, the Yanomami Indigenous health organizations went back to making various reports to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office about the presence of and increase in illegal mining and the chaotic health situation. This was still during the first six months of 2023. The Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, Funai, and the Office of the Special Secretary of Indigenous Health were also informed.

In relation to illegal mining, is leaving the airspace open a mistake, in your experience?

Without question. But there also needs to be surveillance of entries by river.

Were public funds and human resources wasted? When you led Urihi, the NGO reported that public money was being wasted. Yet you were swallowed by government bureaucracy.

Urihi had around 120 employees and 60 Indigenous health agents, 44 of whom were also microscopists working to diagnose malaria. They were trained by us and received diplomas from Funasa. Yes, there is scandalous [financial] waste, happening in the two areas, illegal mining and health, since nothing was resolved. Urihi’s last agreement had an annual expenditure of a little over R$ 8 million [2003/2004 budget, not accounting for inflation]. This was for the NGO to do absolutely everything, not just contract human resources, for 75% of the Yanomami population and 100% of the Ye’kwana.

In a story by SUMAÚMA, geographer Estêvão Senra, who has worked in the territory for over ten years, drew attention to the fact that ‘logistics, as a key issue in Yanomami lands, should have formed the backbone of any plan to restructure the State’s presence in the territory.‘ But there are reports of a tug-of-war in the government, between Sesai and Funai, with the Office of the Chief of Staff being remiss. Upon hearing these reports from experts and Indigenous people, what is your impression?

The Ministry of Defense is totally subservient to the Armed Forces. It is there with the mission of pacifying the military. This is stupid. Based on the Constitution, the Armed Forces are subordinated to the president of the Republic. There was no military coup. Failure to fully exercise this power is a grave political mistake. And I don’t think removing illegal mining is possible without the participation of the Armed Forces. The Office of the Chief of Staff was remiss, of course. It ignored every report, as did the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Funai, Sesai, and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples seem to work in a disarticulated manner and are also remiss. Underneath management, there are a lot of good people rowing against the tide. But nothing progresses.

Despite all the mistakes and omissions, is resolving the situation in the territory possible? How?

It’s just a matter of repeating what was done before, in taking on the first big wave of illegal mining, in the late 1980s, and the resulting health tragedy at that time. The Yanomami can be saved, but the government has already wasted a year. And many deaths could have been avoided. For them, there is no more salvation.

Reportage and text: Malu Delgado

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreading (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (editor-in-chief)

Director: Eliane Brum

Cláudio and Deise left the Amazon in 2004, following political persecution and disagreements with the new health care methods. Photo: Brenda Alcântara/SUMAÚMA