The interim environment and climate change minister, João Paulo Capobianco, headed toward the president’s office on the afternoon of Monday, May 12. He had been called to a meeting with Gleisi Hoffmann, the secretary of institutional relations. With environment minister Marina Silva accompanying Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party) on an official trip to China, Capobianco, the ministry’s executive secretary and Marina’s right-hand man, was hoping he could rely on Gleisi to resolve a major problem.

The Environment and Climate Change Ministry had known since late April that the Senate had decided to fast track a vote on Bill 2159/2021, which became known as the Devastation Bill because it wrecks Brazil’s environmental licensing structure. That is why Marina sought help from the person responsible for articulating the government’s policy, the president’s chief of staff, Rui Costa. She was advised to speak with Gleisi. Appointed to the position weeks earlier, Gleisi was tasked with freeing up the Lula administration’s political articulation, thereby building an alliance for reelection in 2026.

Capobianco crossed the Ministries Esplanade equipped with arguments against the bill and accompanied by aides who were ready to discuss alternatives and the bill’s worst articles. Yet Gleisi preferred to discuss just one issue dear to the ruralist lobby in the Amazon: the embargo issued by Brazil’s environmental regulator, Ibama, on deforested areas. An action that had taken place weeks earlier closed over 70,000 hectares that showed signs of irregularities, blocking the people responsible for these areas from accessing financing, such as federal Plano Safra funds for farmers. Of this total area, over 30,000 hectares are located in the state of Pará. A disgruntled Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement), the governor of the state that will host the COP30, complained to his allies in the Lula administration.

When Capobianco finally found an opening to talk about the Devastation Bill, Gleisi was terse. She responded that both of their press offices could discuss it. The meeting then came to a close. The technical staff that Marina Silva’s aide had taken to the president’s office were never even called into the minister of international relation’s office or taken to talk to her team. Days later, on May 21, the bill passed a full session of the Senate, 54 votes to 13.

Days before the vote in the Senate, Gleisi Hoffmann welcomed the interim environment minister, but did not want to talk about the Devastation Bill. Photo: Gabriela Biló/Folhapress

This is a story of how the Lula government was remiss and helped open the gates of the Senate to pass the “mother of all cattle drives,” another moniker for the Devastation Bill. The attack on environmental licensing is the biggest attack on environmental protections in Brazil in the last over 40 years. It is even worse than the revised Forest Code that passed in 2012.

The text passed by the Chamber of Deputies was already a threat. With the amendments added by the Senate, it became more alarming. Every stage of environmental licensing was relaxed, including studies and impact monitoring. This even applies for potentially harmful developments, such as tailings dams like the one that burst in the environmental crimes of Mariana and Brumadinho, in Minas Gerais. States and municipalities have the right to define what types of developments are exempt from licensing – which, in practice, is likely to encourage a dispute among them to see which state offers the loosest rules in order to attract private investments.

Mariana, buried under mud in Minas Gerais, is a reminder of how an environmental disaster can destroy cities and entire families’ lives. Photo: Moacyr Lopes Junior/Folhapress

A dangerous pause

For the second time, Davi Alcolumbre, a senator from a state in the Brazilian Amazon and a member of the União Brasil party, a fundamental ally of the Lula administration, is presiding over the Senate. The state of Amapá has a wealth of conserved forests, but its social indicators are poor – it has the country’s third worst Human Development Index, as calculated by the United Nations.

There was a twinkle in the politician from Amapá’s eyes when Petrobras asked for authorization to look for oil 160 kilometers off the coast of the city of Oiapoque, in the Foz do Amazonas area. When environmental regulator Ibama denied the state-run oil company’s license to drill in May 2023, due to the risk of an accident in an area that has a strong ocean current and unique ecosystem, Alcolumbre set the government’s environmental governance in his sights. When he was elected president of the Senate in February 2025, he began to act.

Right after taking office, Alcolumbre called meetings with senators Confúcio Moura (Brazilian Democratic Movement for Rondônia) and Tereza Cristina (Progressives Party for Mato Grosso do Sul). They were ordered to reach a consensus on Bill 2159, which amends the environmental licensing process. Confúcio was the bill’s rapporteur on the Environment Commission, while Tereza was its rapporteur on the Agriculture and Agrarian Reform Commission. Simultaneous consideration of a bill by more than one commission is not unusual. It was a way to speed its journey to a plenary session.

In alignment with the Lula administration, in November 2023 Confúcio had introduced a report (an analysis of the bill, suggesting changes and tweaks) that was produced in collaboration with various government ministries, including Marina Silva’s. It wasn’t the text that either the Environment and Climate Change Ministry or the environmentalists dreamed of, but it also wasn’t the “free for all” the ruralist lobby, industries, mining companies, and the companies behind large infrastructure projects had called for. Because of this, it would not easily pass the Environment Commission unless the government made strides with senators in the “Centrão,” the name given to the bloc of right and center-right parties who give Lula support in exchange for ministerial appointments. Strides that were never made – the text was shelved in the end.

Tereza Cristina wanted the Senate to ratify the bill passed by the Chamber of Deputies in 2021, which was much worse for the environment than Confúcio Moura’s initial report. The very politically-savvy senator is the main leader of the Agricultural Parliamentary Front in the Chamber. She also served as minister of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply under the far-right former President Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party). A patient Tereza preferred to wait and see if Confúcio would find success in passing his report. She lay in wait until the scenario shifted. As it did.

Confúcio Moura and Tereza Cristina, the people behind the version of the Devastation Bill the Senate voted on and passed. Photo: Geraldo Magela/Agência Senado

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one source who actively participated in the negotiations told SUMAÚMA that the Lula administration put forth huge efforts in 2023, the first year of the now-president’s term, to build a reasonable report for Bill 2159. With the chief of staff actively intermediating, regular meetings were held by aides to Confúcio Moura and aides from the Environment and Climate Change Ministry and from other areas of the government. It was because of this that the text proposed by the senator from Rondônia in late 2023 came to light.

Yet in 2024 the bill seemed to have been removed from the chief of staff’s list of priorities. With Marina Silva’s team asking questions but receiving no answers from the government’s policy area, Confúcio said he had his “hands tied.” The senator confirmed this himself at two Environment Commission hearings. On May 13, he recalled how the discussion “had the initial participation of the chief of staff, whose team was made available.” However, “later, the government was absent, missing,” in the senator’s own words. One week later, on May 20, he again brought up the subject: “For some time now, [government representatives] have started to be absent. They went six months, seven months with no contact. Then I said: ‘Tereza, the two of us are going to have to resolve it, because it’s taking too long, nobody is saying anything.’”

The moment Tereza Cristina was waiting for had arrived.

Preparing the steamroller

After encouraging Confúcio Moura and Tereza Cristina to work toward a consensus, Davi Alcolumbre went after Fabiano Contarato, a senator for Espírito Santo. Elected as a candidate for the Rede party, Marina Silva’s party before she switched to the Workers’ Party in 2021, he had always been sympathetic to the environmental agenda. In 2025, he became the president of the Senate Environment Commission.

While talking with Alcolumbre, the senator from Espírito Santo was convinced that it wasn’t possible to wait any longer: the commission had to vote on a text for Bill 2159. Otherwise, the Senate president reminded him, he could override the commissions and order the text to be sent to a direct plenary vote. The message was clear – the bill would progress, whether for good or for bad. Contarato promised he would put it to a vote.

Fabiano Contarato acted with sincerity, but it was ‘unfortunate’ that he assessed the seriousness of the Devastation Bill ‘alone and erroneously.’ Photo: Lula Marques/Agência Brasil

Although the warning signs only began to flash in late April at the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, early in the month it was already public knowledge that the steamroller had begun moving. An article published on April 4 by the Senate’s official news outlet, Agência Senado, was clear: Confúcio Moura said Contarato had asked for the issue to be “resolved within 30 days.” Weeks later, on May 7, Confúcio would confirm the rush in a session where the report he produced with Tereza Cristina began to be read. “You gave us a deadline, which is today, and we’re meeting the deadline for submitting this report – very rushed.”

The report, which came out exactly to the liking of ruralists, miners and developers, was a mortal blow to environmental protection. It was only then that the government’s leader in the Senate, Jaques Wagner (Workers’ Party, representing Bahia), entered the foray to try to postpone a vote. “I think this is a very delicate matter. We’re at the door to the COP30. It’s not that I want to put it off, [rather I want] to gain at least one more week,” he said. He got two. A vote on the commissions’ report was scheduled for May 20.

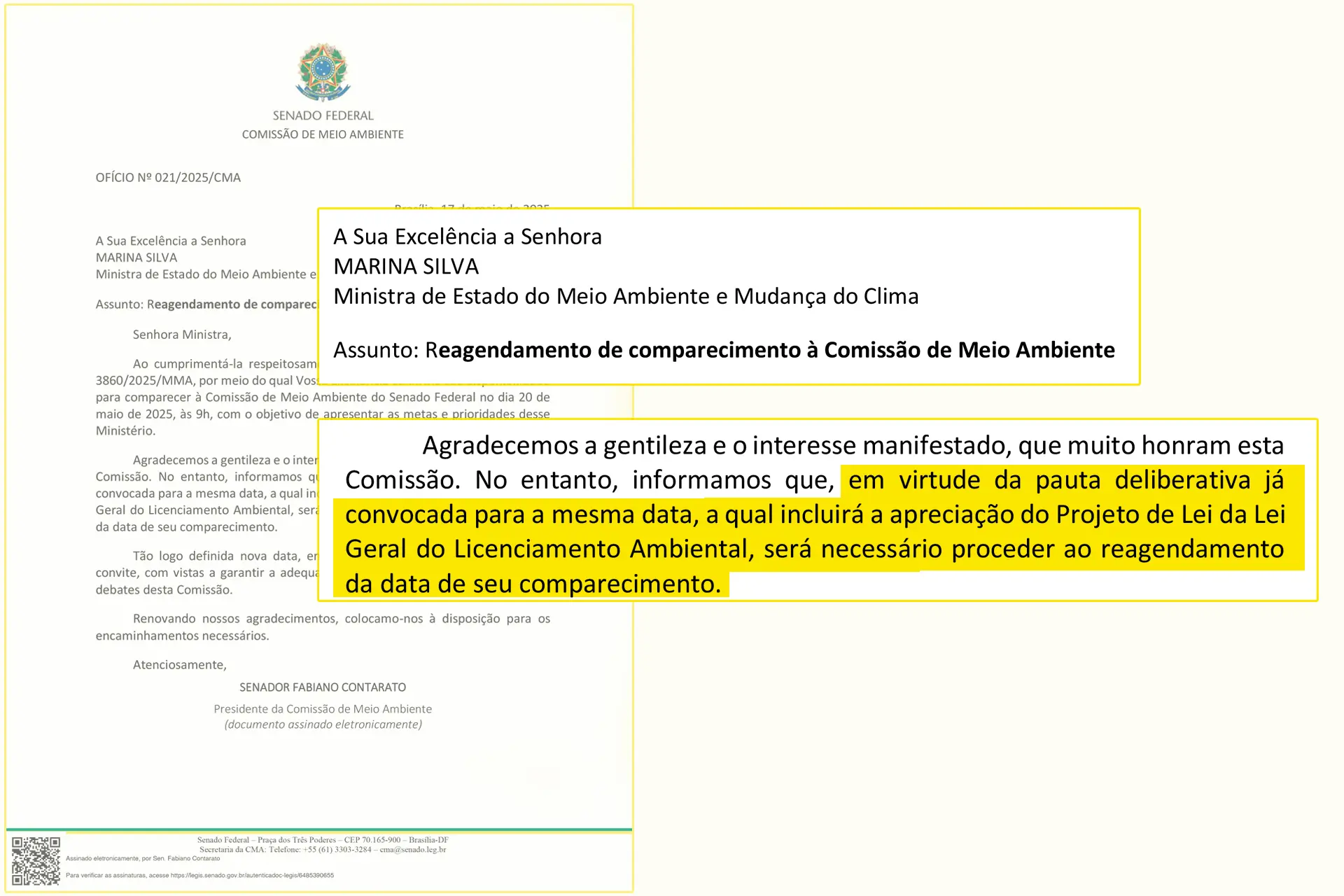

This, however, was the same day that the Environment Commission had invited Marina Silva to talk about her work at the ministry. To avoid the embarrassment of listening to the environment minister speak out against a bill that Contarato knew would then be passed, the senator withdrew her invitation. “We would like to thank you for your kindness and the interest expressed, which are a great honor to this Commission. Nevertheless, because of the agenda of deliberations already set for the same date, which will include consideration of the Bill on the General Environmental Licensing Act, we will need to reschedule the date of your appearance,” reads the official text sent by the parliamentarian from Espírito Santo. “Obviously [if the invite had not been withdrawn] I was going to very emphatically raise this issue [about the problems with the bill],” Marina said days later, on May 22, to cable TV news outlet Globonews.

The official letter sent by Fabiano Contarato to Marina Silva, postponing the minister’s visit to the Senate so he could open up space to vote on the Devastation Bill. Photo: screenshot

Contarato’s work in conducting the matter has garnered criticism among Marina’s aides and environmentalists. There was frustration for anyone who had expected the senator from Espírito Santo to notice how bad the report’s contents were and stave off a vote – a worst-case scenario that would force openly aggressive action from Davi Alcolumbre, ignoring the commissions and filing the text directly to the plenary. “Between keeping his word to Alcolumbre and being politically coherent, he chose to keep his word,” one member of the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, who asked not to be identified, told SUMAÚMA.

On May 19, on the eve of an Environment Commission vote on the report by Confúcio and Tereza, Contarato agreed to closed-door meeting to speak with a small group of civil society representatives from environmentalist organizations. SUMAÚMA spoke with two people who were at that meeting and whose accounts were identical. They said Contarato showed his “sympathy” for the environmental agenda. He complained he was under “a lot of pressure” and was being given “no guidance” from the president’s office. He said that as the commission president, he needed to be “unbiased,” and that he wouldn’t go back on his promise to put the text to a vote.

“He argued that it would be worse if the text went straight to the plenary,” one person at the meeting said. In the end, as it became clear, it made no difference. “Contarato acted with sincerity, but he assessed the situation alone – and erroneously. It was very unfortunate.”

SUMAÚMA contacted the press office of Senator Fabiano Contarato about an interview and was told the senator would answer questions in writing. In a statement, he argued the Devastation Bill “had already been going through official channels for decades” and that “regimentally it was possible for the text the Chamber passed to be considered directly by the plenary session, without going through the commissions.”

On May 20, before putting the text to a vote in the Senate Environment Commission, Contarato gave a short speech. “We have to understand the gravity, the complexity of this bill. I am appealing to my fellow senators to have the serenity, sovereignty and balance to understand the positives and the negatives.” This also made no difference. The joint report by Confúcio Moura and Tereza Cristina passed late that morning, through a show of hands – something that only occurs when votes don’t need to be counted, because an agreement has already been finalized on the matter. That afternoon, it would just as easily pass the Agriculture and Agrarian Reform Commission.

In the break between one session and another, Tereza Cristina and other senators headed toward Brasília’s Lago Sul district, where the Instituto Pensar Agropecuária maintains a mansion where the Agricultural Parliamentary Front holds its meetings. Luncheons featuring special guests are usually held on Tuesdays. In addition to the usual rural industry organizations, these guests include Davi Bomtempo, the environment superintendent at the National Confederation of Industry, and Lula’s agriculture and livestock minister, Carlos Fávaro, who argued in favor of the bill’s passage. “We worked hard on this bill. It will be a milestone in the country’s development, generating countless opportunities for Brazil,” the minister said in his speech.

That same day, a document was released by the ruralist lobby. Signed by 98 business organizations, it advocated for the immediate passage of the Devastation Bill. The steamroller was ready to move in the Senate’s plenary session.

The Devastation Bill’s supporters: Minister Carlos Fávaro (at left, smiling) and Davi Bomtempo, of the National Confederation of Industries. Photos: Beatriz Batalha/Ministry of Agriculture and Bruno Spada/Chamber of Deputies

Grateful oil industry

Wednesday, May 21, was an especially busy day at the National Congress. Mayors from across the country who had gathered in Brasília for an annual march used the day to tour congressional offices. Concerned about serving their electoral bases, the parliamentarians were late to arrive to the plenary session. But Davi Alcolumbre was in a hurry.

When the bell signaling the start of voting rang, at 4:37 PM, the Senate president asked lobby leaders and advisers to warn the senators that they needed to head for the plenary session. “We have a very important matter: environmental licensing.” Throughout the session and in light of the delayed arrival of the parliamentarians, the order was repeated several times.

Tereza Cristina began reading the report at 6:24 PM. She had “as much time as needed” to “demystify lies” about the bill, Alcolumbre ensured her. “I want to thank president Davi, who undertook the task of no longer postponing this matter,” the senator said. A series of last-minute amendments to the text were then accepted, including one from Alcolumbre that creates a political assessment by the federal government for environmental licenses for any “strategic venture” – which would, for example, allow licensing to be granted at record speed for drilling activities in the Foz do Amazonas area, in Alcolumbre’s state of Amapá.

The world’s largest contiguous area of mangroves, in Amapá, is threatened by the drilling Petrobras wants to do in Foz do Amazonas. Photo: Enrico Marone/Greenpeace

The senator finished reading the report at 7:10 PM. This was followed by a line of senators speaking in support of the bill and against Marina Silva. People like Senator Omar Aziz (Social Democratic Party), who represents Amazonas: “The Amazon is not the world’s, it’s Brazilian. […] Because there are fanatics, there are people who are working for conglomerates, for international issues and not for Brazilian ones. The government is to blame too for putting the wrong people in the right places. The people who know what it’s like living in the Amazon are the ones living there, the ones residing there, not someone who went to be a candidate in São Paulo.”

Environment and climate change minister Marina Silva was born in the Amazon Rainforest. The daughter of a Ribeirinha family of rubber-tappers in Acre, she was active in opposing deforestation alongside Chico Mendes, who was murdered in 1988 for his fight for the workers of the forest. Marina only learned to read and write when she was 16, through a public literacy program she attended after moving to Rio Branco to receive medical treatment. She finished a high school equivalency program while working as a domestic and later passed a college entrance exam to study History at the Federal University of Acre. There, in 1980, she helped found the Workers’ Party, of which she was a member while serving as a city council member, congressional deputy, senator, and environment minister from 2003 to 2008. She left the Workers’ Party and joined the Brazilian Socialist Party before founding Rede, through which she was elected as a federal deputy representing the state of São Paulo.

She didn’t stop there. Another person who spoke was Senator Marcos Rogério (Liberal Party), a Bolsonaro supporter who represents Rondônia: “You can’t lock up Brazil in the name of an ideology. It’s impossible to live without some type of aggression toward the environment.” Yet the person who best summed up what was at stake was another Bolsonaro backer, Senator Luis Carlos Heinze (Progressives Party) of Rio Grande do Sul: “Our agriculture says thanks, our mining says thanks, our oil says thanks, our roads, highways, railways, waterways, ports and airports say thanks.” The three were on opposite sides of the Parliamentary Inquiry Commission on the Covid-19 Pandemic: the latter two were among the loudest defenders of the positions taken by Jair Bolsonaro during the biggest pandemic in a century. Aziz presided over the inquiry, which recommended indicting the far-right president for crimes against humanity. Now, they are together against the environment.

According to Luis Carlos Heinze (left), ‘our oil says thanks’ for the Devastation Bill. Omar Aziz thinks environmental protection is for ‘fanatics.’ Photos: Zeca Ribeiro and Vinicius Loures/Chamber of Deputies

It was only just four hours after the session started, at 8:15 PM, that a voice spoke out against the bill – it was Fabiano Contarato. “There’s something Father Júlio Lancellotti says, Senator Tereza, that I find quite moving: ‘I don’t fight to win. I know I’m going to lose. I fight to stay faithful until the end.’” Contarato defended his stance on the Environment Commission – “I can’t, because of some pedantry or some whim of mine, fail to debate and to file bills that I consider important to the nation, even if I’m going to lose that vote.” He then asked Tereza Cristina to remove an article from the text that would allow for the possibility of self-licensing for developments with “average polluting potential.” His request was not granted.

Besides Contarato, only Leila Barros (Democratic Labor Party), a senator for the Federal District, took to the floor to speak against the bill. She called for more discussion. “This debate is not mature, even if it has been 20 years [of processes]. It was shelved for [most of] 20 years,” she argued. Like Contarato, she was ignored.

Voting ended at 9:28 PM: 54 votes in favor and just 13 against. Eight no votes came from the Workers’ Party – the party had decided against the bill. Randolfe Rodrigues, the government’s leader in Congress, opted to miss the session to avoid voting. “Just a little while ago he was here and he said that I could share that he would have voted against the report submitted,” Alcolumbre said. Like him, Randolfe also represents Amapá in the Senate – and he broke with Marina Silva to defend oil exploration along Amazonian shores.

Jaques Wagner, the government’s leader in the Senate, was also absent from the plenary session during voting – although he did vote remotely against the bill. So, it was up to Leila Barros, the deputy leader, to announce that the lobby supporting Lula would be free to vote however they wished. Once voting ended, Leila, seeing that the climate was not going to be amenable to overturning the worst parts of the report in separate votes – what in parliamentary jargon is known as detachments – capitulated. “I’m withdrawing the detachment,” she announced at the microphone. She was applauded by the plenary.

“I fought the good fight,” she said in resignation.

According to newspaper outletO Globo, foreign relations minister Gleisi Hoffmann had met with senators from allied parties (the Brazilian Democratic Movement, União, Social Democratic Party, Brazilian Socialist Party, and Democratic Labor Party) on the eve of the vote, but she supposedly did not ask them to oppose the Devastation Bill. An aide to the minister hit back against this information to SUMAÚMA, saying that Gleisi told them the government was against the text. “They want to hold the minister responsible for a decision by senators,” the aide said.

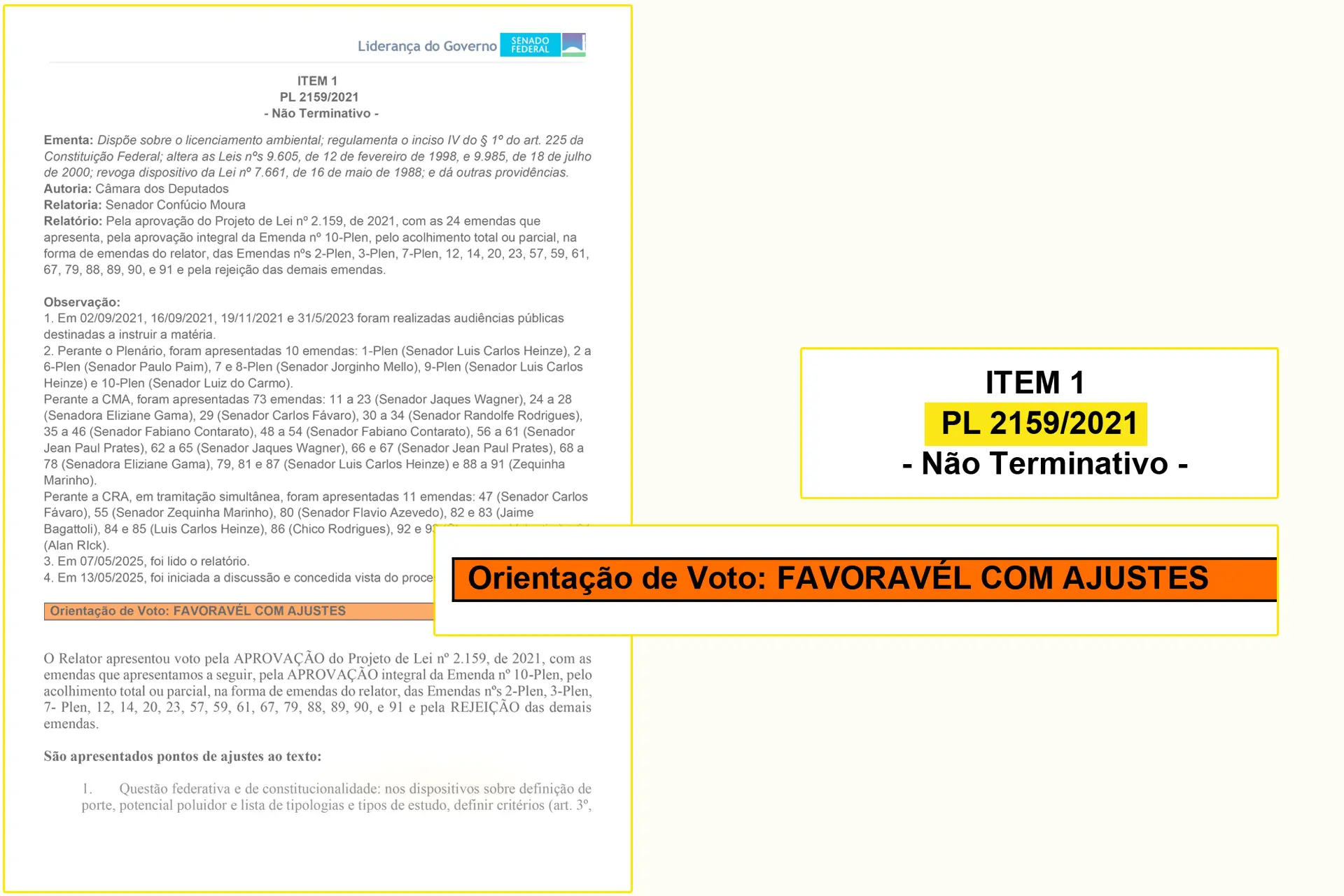

However, a document on the text that was prepared by the government’s leaders in the Senate, which SUMAÚMA obtained, tells a different story. Although it highlights problems with the bill, it establishes a position that is “favorable to changes and adjustments to the text.” The changes and adjustments were never made.

“The government’s policy area washed its hands,” political scientist Marcos Woortmann says ruefully. He is the adjunct director of the Democracy and Sustainability Institute, a social and environmental organization founded in 2009, based on the idea that sustainable development can only be achieved with broad participation by society in politics. “They’re tossing the environment to the lions, and this is strengthening opposition to the government itself. The people benefiting from the destruction of environmental licensing will not be with Lula in 2026, they’ll be with the far right. The government is mortally weakening the issue that has the most repercussion and international legitimacy, that speaks to middle class sectors who aren’t on the left, but who voted for Lula in defense of democracy and who are also concerned about what Bolsonaro could do to the environment.”

A document from the government’s leaders in the Senate advises a ‘vote in favor’ of the Devastation Bill. Photo: screenshot

SUMAÚMA sent a list of questions to Davi Alcolumbre. Instead of answering them, his press office sent over a copy of the speech read by the senator right after the Devastation Bill passed. “I will sleep tonight with a sense of fulfilling my duty,” he said from the senate president’s desk. “Many would rather see Brazil paralyzed, with over 5,000 projects deadlocked, held hostage to bureaucracy and ideological positions that do not see the reality of those who need bridges, roads, energy and infrastructure to live with dignity,” he said, in a subtle dig at Marina Silva. Environmental conservation is, however, far from what politicians like Alcolumbre define as “ideology.” On the contrary, it is crucial to controlling the climate emergency and to human survival. Since May 23, SUMAÚMA has been reaching out to the press office of the Environment and Climate Change Ministry for comment on what happened behind the scenes with the bill, but had not received a response by the time this story went to press.

‘It’s a cruel thing’

Luciano Zica is the first name that appears among the authors of Bill 2159. He was a member of the Workers’ Party and the leader of the environmentalist lobby when he, along with several colleagues, introduced what was a bill to define rules that would guarantee environmental protections against impacts from major projects. A former oil man from around Campinas, the largest city in the inland São Paulo area, Zica is to an extent an accidental environmentalist. “What made me become an environmentalist was the mission of paying for the sins we committed due to a lack of environmental policy in my time as a refinery operator,” he told SUMAÚMA. He worked at the Petrobras-owned Paulínia Refinery, the country’s largest, near Campinas. “It was a payment on an environmental debt,” he explained.

Over the years, Zica’s text was seized and cannibalized by politicians connected to large developers, industries, and mining companies and to the powerful ruralist lobby. The man who gave the final form to the text passed in 2021 by the Chamber of Deputies was Bolsonaro supporter Neri Geller, then a Progressives Party deputy representing Mato Grosso who also served on the Agricultural Parliamentary Front. A detailed report by journalist Roberto Kaz, published in Piauí magazine in August 2021, goes into the intricacies of the metamorphosis of the text that Zica does not recognize as his own today.

“Out of what I proposed, they only kept a few periods and commas,” he says ironically. “It’s a cruel thing for me to appear as the author of a proposal as absurd as this. I’m embarrassed to be the first signatory. This was not what we proposed. If I knew that it would be considered in this current situation, I would never have introduced it,” he says. Zica served as a deputy until 2007. He left the Workers’ Party shortly after, bothered by what felt was a lack of support in the mayoral election in Campinas. Zica helped Marina Silva organize and found Rede, the party the minister is currently a member of, but which he never joined. “But I continue fighting and voting for the left.”

Zica believes the Lula administration did not work to stop the Devastation Bill. “In the current political situation, the government is being held hostage by Congress,” he said. “We’ve lost Parliament as a space for formulating proposals in the public and collective interest. It has become a space merely for corporate interests, for economic interests.” That is why Zica has not been involved with politics since 2010. On the other hand, Neri Geller at one time worked for the third Lula administration – he was the secretary of agricultural policy at the Agriculture and Livestock Ministry, but he was let go in June 2024 after being suspected of irregularities in bids to purchase rice.

Geller was brought into the Lula administration by Carlos Fávaro. Yet the agriculture and livestock minister wasn’t the only member from the upper echelons to argue in favor of a bill that mortally wounds environmental protections. “I defend this text,” the transport minister, Renan Filho, told O Globo. He is the son of Senator Renan Calheiros (Brazilian Democratic Movement), who represents Alagoas and is one of the main leaders of the Centrão bloc. Weeks prior, as the newspaper recalled, Marcos Cavalcanti, the secretary of the federal government’s Partnerships and Investments Program, who worked with Rui Costa in the government in Bahia, had said at a public event that the “government’s position is completely in favor of the so-called Environmental Licensing Act,” considered “one of the structuring actions of the Accelerated Growth Program.” The legacy left to the country by this program, which was established by Workers’ Party administrations, includes projects during previous administrations like the Belo Monte Dam and it has now being reissued in the current administration. The president’s office is betting that major works will pave the way to reelection.

While serving in the Chamber of Deputies in 2021, Neri Geller built the basis of the Devastation Bill. In 2023, he went to work for the Lula administration. Photo: Bruno Spada/Chamber of Deputies

To hell with decorum

Late in the morning on Tuesday, May 27, Marina Silva went to the Senate for the first time after the Devastation Bill had passed. She was answering an invite from the Infrastructure Commission, which in practice was a trap. Empowered by the steamroller-style victory from the previous week, the senators weren’t the least bit worried about maintaining parliamentary decorum.

The minister the targeted of sexism and misogyny from the commission’s president, Bolsonaro ally Marcos Rogério: “Stay in your place,” the senator barked, cutting Marina Silva’s microphone off several times and preventing her from defending herself. Marina Silva would later say that: “My place is the place of defending democracy, my place is the place of defending the environment, of fighting inequality, of sustainable development, of protecting biodiversity, of infrastructure projects needed for the country. […] What cannot happen is for someone to think that because you’re a woman, you’re Black, you come from a humble background, that you will say who I am and even say that I should stay in my place. My place is where all women should be.”

Marina was also attacked by Amazonian politician Omar Aziz, who voted for the Devastation Bill and celebrated it, but outlined a twisted logic according to which Marina was responsible for the text passed, as if it were Parliament’s revenge for her presence in the government. When another of Amazon’s Bolsonaro-supporting senators, Plínio Valério of the Social Democratic Party, said he “respected women, but not the minister,” she demanded an apology. Valério, who has previously stated his wish to choke Marina, refused and she left the session.

Jaques Wagner, the government’s leader in the Senate, was there for most of the session, but had stepped out when Valério issued the attacks that caused the minister to get up and leave. It was up to a Workers’ Party colleague, Senator Rogério Carvalho of Sergipe, and to Senator Eliziane Gama (Social Democratic Party) of Maranhão to defend the minister.

Marcos Rogério – who defended Jair Bolsonaro during a parliamentary Covid inquiy – berates Marina Silva. The minister got up and left. Photo: Geraldo Magela/Agência Senado

On her way out, Marina shared her frustration. “It is my duty to defend Brazil’s natural resources, to go from ‘you can’t’ to ‘how can you,’ in the right way. I choose not to go back to the days of Balbina, of Cubatão, where things are done without any concern for the environment,” she told journalists. Reaction to the attacks was so strong on social media that the politicians who gave the Devastation Bill free rein found themselves forced to come out in defense of Marina Silva. Gleisi Hoffmann released a brief public statement, in which she called the behavior by Marcos Rogério and Plínio Valério “inadmissible,” expressing her “condemnation of the aggressors” and the “total solidarity of President Lula’s government” with Marina. Randolfe Rodrigues took to the Senate floor to defend the environment and climate change minister.

Later, in an interview with Globonews, the minister sent her gratitude to Lula. “The president made a point of calling me [after the aggression in the Senate], he told me: ‘You did the right thing not to tolerate disrespect.’ And I’ll say, as a matter of justice: everything I’ve managed to do here is with Lula directly supporting it. I feel backed by the president’s support. But we’re a government with a wide coalition, and I understand the need for our partners who make up the wide coalition, and I want people to also make up the wide coalition I represent, of Brazil’s social and environmental agenda.”

Marina’s statement can be read as recognizing the president for the support he gave her on issues such as the goal of zero deforestation. But it can also be interpreted as an admission that, without the president’s action, the environmental and climate agenda is suffocating within the government itself. In the case of the Devastation Bill, Lula did nothing to stop the steamroller.

Days before the session where Marina was subjected to public insults, Davi Alcolumbre crossed the Praça dos Três Poderes to be honored at the imposing Ministry of Justice and Public Security building, which sits next to the president’s office. On May 23, two days after exploding Brazil’s environmental licensing, of which he is the “main articulator,” according to Agência Senado, Alcolumbre was given the Medal of Order of Merit’s highest honor, the Grand Cross, by justice minister Ricardo Lewandowski, “for the relevant services provided to all of Brazilian society.”

In politics, things rarely happen by chance.

Two days after passing the Devastation Bill, Davi Alcolumbre received the highest honor given by the Ministry of Justice. Photo: Isaac Amorim/Ministry of Justice and Public Security

A statement from the Environment and Climate Change Ministry

SUMAÚMA reached out to the Environment and Climate Change Ministry on May 23 regarding the Devastation Bill. We sent a list of questions and spoke with a press representative. However, the ministry only sent a statement one hour after our report went to press.

We are publishing the full response below:

The Environment and Climate Change Ministry would like to clarify that the information described represents isolated facts that lack appropriate context, a situation that can lead to distorted interpretations of the inter-ministerial articulation regarding Bill 2159/21. The new report on the proposal was introduced by Senator Confúcio Moura in the Senate Environment Commission on May 7, already quite near the date when it was put to a vote.

The meeting held on May 12 between the interim environment and climate change minister, the interim chief of staff, and the secretary of institutional relations was scheduled to discuss other matters related to the environmental agenda. At the time, the secretary of institutional relations named the technical team responsible for assessing Bill 2159/2021, with which the Environment and Climate Change Ministry began an intense dialog. Note that on May 13, the day following the meeting between the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, the secretary of institutional relations and the Chief of Staff, a collective request for the Senate Environment Commission to access the bill was granted.

The Environment and Climate Change Ministry maintains a constant dialog with the president’s Chief of Staff and the secretary of institutional relations on Bill 2159/2021 and various other matters in the environmental agenda, in alignment with the federal government’s guidance. The qualified technical analysis and defense of constitutional principles that govern Brazil’s environmental policy serve as the basis for the Environment and Climate Change Ministry. It is therefore baseless to say that the Environment and Climate Change Ministry was prevented from speaking or participating in discussions related to the bill.

SUMAÚMA never suggested that the Environment and Climate Change Ministry was prevented from participating in negotiations on the Devastation Bill – as can be read in the story published.

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing:Fernanda da Escóssia, Eliane Brum and Talita Bedinelli

Art Editor: Cacao Sousa

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes and Caroline Farah

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum