Eight thousand cubic meters per second. This is the key figure in the debate over the environmental and humanitarian catastrophe caused by Belo Monte hydroelectric plant in the Xingu River’s Volta Grande (Big Bend) – as the 130-kilometer stretch of one of the Amazon’s most biodiverse regions is called. Eight thousand cubic meters per second is the maximum amount of water that Norte Energia, the dam’s concessionaire, earmarks for the functioning of ecological systems and for the lives of the three indigenous peoples and various traditional riverbank communities who are affected. The figure is a quota for the river’s peak monthly flow, which under natural conditions would be almost three times highert: 22,000 cubic meters. Eight thousand cubic meters is the amount of water that condemns hundreds of fish species to death, as they are unable to reproduce, and takes protein off the tables of the Big Bend’s inhabitants. Eight thousand cubic meters per second is an insufficient volume of water that can kill 70% of the region’s floodable forests.

This figure has caused an implosion of both human and non-human life in the Big Bend of the Xingu, and put an entire ecological system at risk of death, but where does this number come from?

Gilliarde Juruna, from the Paquiçamba Indigenous Land, films the Technical Seminar ‘The Future of the Big Bend of the Xingu River’, organized by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office at the headquarters of the Attorney General’s Office, in Brasília. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

This is the question that some of Brazil’s most important scientists have been asking Norte Energia for years and to which they have never had an accurate answer. At the technical seminar “The Future of the Big Bend of the Xingu”, which was held on March 14 at the Attorney General’s Office in Brasília, the researcher Jansen Zuanon unraveled the mystery. The scientist, one of the most recognized Amazon fish experts, was only able to discover the answer because Norte Energia S.A. filed a motion in an attempt to “challenge” the seminar. Jansen, a retired researcher from the National Institute for Amazon Research (Inpa), is a member of the Observatory of the so-called Big Bend of the Xingu, working in collaboration with indigenous people and riverside dwellers, with due regard to the scientific knowledge of those who are the greatest experts when it comes down to rivers and fish.

The week before the seminar, Belo Monte’s concessionaire sent an official request to the Attorney General’s Office to cancel the event. The company claimed the issue was a “technical” one and that it was up to the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama) – rather than the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF) – to analyze the viability of the hydrographs (flow of water at a certain point over a certain period of time) of the Big Bend of the Xingu. The company also complained that the information presented would be “one-sided”.

The Federal Public Prosecutor Office gave a brief response to Norte Energia’s request: the seminar was confirmed as was the role of the institution to monitor the damage caused by the plant. They also invited Norte Energia to send its representatives. Officially, nobody showed up to represent the concessionaire, although there were people recording the event wearing T-shirts of third-party contractors hired by the company.

One of the justifications used by Norte Energia in the motion it filed to have the event “canceled” caught Jansen Zuanon’s attention. Norte Energia S.A. finally revealed the location of the supposed empirical support for the 8,000 cubic meters per second figure, within the dozens of volumes of Belo Monte’s Environmental Impact Studies (EIA):

“I always had this doubt,” confessed Jansen during the seminar. “We have been talking about this hydrograph and about these 8,000 cubic meters for many years now. And we were always asking the company and Ibama where this figure came from, and what it is based on. On a number of occasions, they said that modeling had been done, but they never presented it. We challenged Norte Energia to show where this figure had come from, to say how this number supported the hydrograph from the socio-ecological point of view. But nobody ever showed us the data. They merely said it was in the Environmental Impact Study (EIA). But where in the EIA? The answer we were given was that ‘we don’t know, there are a lot of volumes’. There really are a lot of volumes, but we wanted to know: what did you measure, which variables did you take into account to demonstrate that it was sustainable to divert most of the water? Was it the amount of fish spawning, the area of forest being flooded, what was the variable? Oh, I don’t remember, I didn’t do it, I don’t know where it is… those were the answers that we were always given.”

And then, in the motion that was filed to cancel the event, there it was: volume 31 of the Environmental Impact Study. Jansen immediately examined this passage:

“I went and reread volume 31 and looked for that figure of 8,000 cubic meters of water. The only time this number appears is in an ichthyoplankton report, about fish larvae. Believe it or not: a study was indeed done, in 2008, with three months of sampling, in February, March, and April. According to the conditions of the time, when this study was carried out, the river’s flow was one of 8,000 cubic meters per second. For some reason, larvae collection was highest in February, and as the flood increased, the number of larvae dropped. There were 36 collection points in 5 different types of environments and 173 fish larvae were collected in February, 73 in March, and 3 in April: a total of 249 fish larvae.”

The scientist continues, in front of a confused audience:

“The study’s conclusion is that the flow rate of 8,000 cubic meters was the period with the highest density of larvae, so that would be the most important time and this flow rate should be good enough for all species of fish. That is what is written in the report. And that’s it. That is where the figure of 8,000 cubic meters came from. It is the only support with empirical data to say that 8,000 would be enough. You can go through the entire Environmental Impact Study, there is nothing else. And from the modeling with 11 scenarios that is presented in the Environmental Impact Study, five are unfeasible according to the authors of the studies themselves. And then, setting aside 14,000 cubic meters for the turbines, how can we sustain the difference of 8,000 that is left for the Big Bend? It is a house of cards, but one that only has two cards: the increase in the flow and the greatest number of larvae in the month of February in a single year. There is no argument, no logic, no support, no empirical, biological or ecological data that supports 8,000 cubic meters per second as the best flow capable of keeping ecological systems working in the Xingu. I was stunned.”

Scientist Jansen Zuanon, an expert on Amazon fish, shared his knowledge and doubts in a speech during the seminar: ‘There is no empirical, biological, or ecological data that guarantees that 8,000 cubic meters per second is the best flow rate, capable of keeping ecological systems functioning in the Xingu. I was stunned’. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

In summary: the figure that has been used for four years in the Xingu’s Big Bend and which is causing an environmental and human catastrophe in a part of the world’s largest rainforest where you have endemic fish species is based on an unsustainable conclusion that can easily be challenged, which was extrapolated from a flimsy, substandard study, conducted in an atypical year. It was the result of three months of collection in a single year and with a very low number of larvae, which any scientist or even a layman can realize was a devious misuse of insufficient data, simply to justify the hijacking of water for the turbines. By approving these studies, Ibama allowed the disaster to occur. As fisherman Raimundo da Cruz e Silva said at the seminar: “Belo Monte was a catastrophe foretold, now it is a catastrophe experienced. “And the explanation can be found there in volume 31 of the Environmental Impact Study.

The extinction of the “fish forests”

The presence of representatives from the Office of the Chief of Staff, the ministries of Indigenous Peoples, Environment, Science and Technology, and the National Water Agency shows that Lula’s third administration may be willing to finally comply with the law regarding the disastrous hydroelectric dam on the Xingu. The president of Funai (the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples), Joenia Wapichana, and the president of Ibama, Rodrigo Agostinho, were both at the table. Juma Xipaia, the cacique of her people in the Middle Xingu, which has also been affected by Belo Monte, represented the Minister of Indigenous Affairs, Sonia Guajajara.

The authorities listened to the indigenous and riverside researchers who have been monitoring what is happening to the water flow in the Big Bend of the Xingu on a daily basis for nine years, conducting high-level and therefore reliable research. Together with scientists from several universities in the country, in an alliance between forest science and academic science, they proved that 8,000 cubic meters of water per second is incompatible with life. They showed the audience images of the millions of dead fish eggs that were taken this February, in an environmental disaster revealed by SUMAÚMA that will further reduce the amount of protein on the families’ tables over the next three years.

In her speech at the seminar, Sara Rodrigues, a fisherwoman from the Baleia community, called the proposed water division applied by Norte Energia a hydrograph of death. “For us development was a fertile river that was full of life, which we had and have now lost.” Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

Jansen Zuanon’s revelation was one of the most compelling moments during an afternoon of reports about the catastrophe faced by the Big Bend’s populations since the Pimental dam (Belo Monte’s main dam) was closed in 2015. Sara Rodrigues, a fisherwoman from the Baleia community, called the proposed water division applied by the company a “hydrograph of death.” “We ourselves are experiencing cruel development, the development of greed, this development is not one that is good for us. For us development was the fertile river that was full of life, which we had and have now lost. The whole ecosystem is compromised,” she said in a voice choked with emotion. She is one of the researchers who produces daily data regarding the situation of the Big Bend. Her conclusions were confirmed by the researcher Camila Ribas, from the National Institute for Amazon Research (Inpa). She was emphatic: the floodable forests, which are known as igapó forests in the Amazon region, cannot survive without flooding.

“The ecological cycle has governed the Xingu’s Big Bend for thousands of years and all the region’s plant and animal life is adapted to it, so it needs the river’s flood pulse. When you read in the monitoring studies that Norte Energia presented to Ibama that there is no impact from the diversion of the water into the Big Bend it feels like you’re reading a joke. When they say that no trees have died it is simply because there hasn’t been time yet,” she states. The scientist brought studies from the region of the Balbina power plant which show that three to five years after the end of the seasonal flooding, the forests start to disappear.

These are profound, serious impacts, with knock-on effects in the Amazon region. For the researchers who presented their data at the seminar, the igapó forests, which are defined by fisherman and writer Raimundo da Cruz e Silva as “fish forests”, are doomed to disappear completely in the region if there are no adjustments in the hydrograph. They have already presented Ibama with a proposal for a proven ecological hydrograph that ensures the survival of at least some of these forests. André Sawakuchi, from the University of São Paulo described what is happening right now in the Xingu as a dispute over the waters – rather than a sharing. In order for it to really be a sharing, he says, it will be necessary to change paradigms and start off on the basis of the technical criteria presented to Ibama. In order for it to be a sharing it is necessary to respect life and the reproduction of life.

“Laughable” mitigation efforts

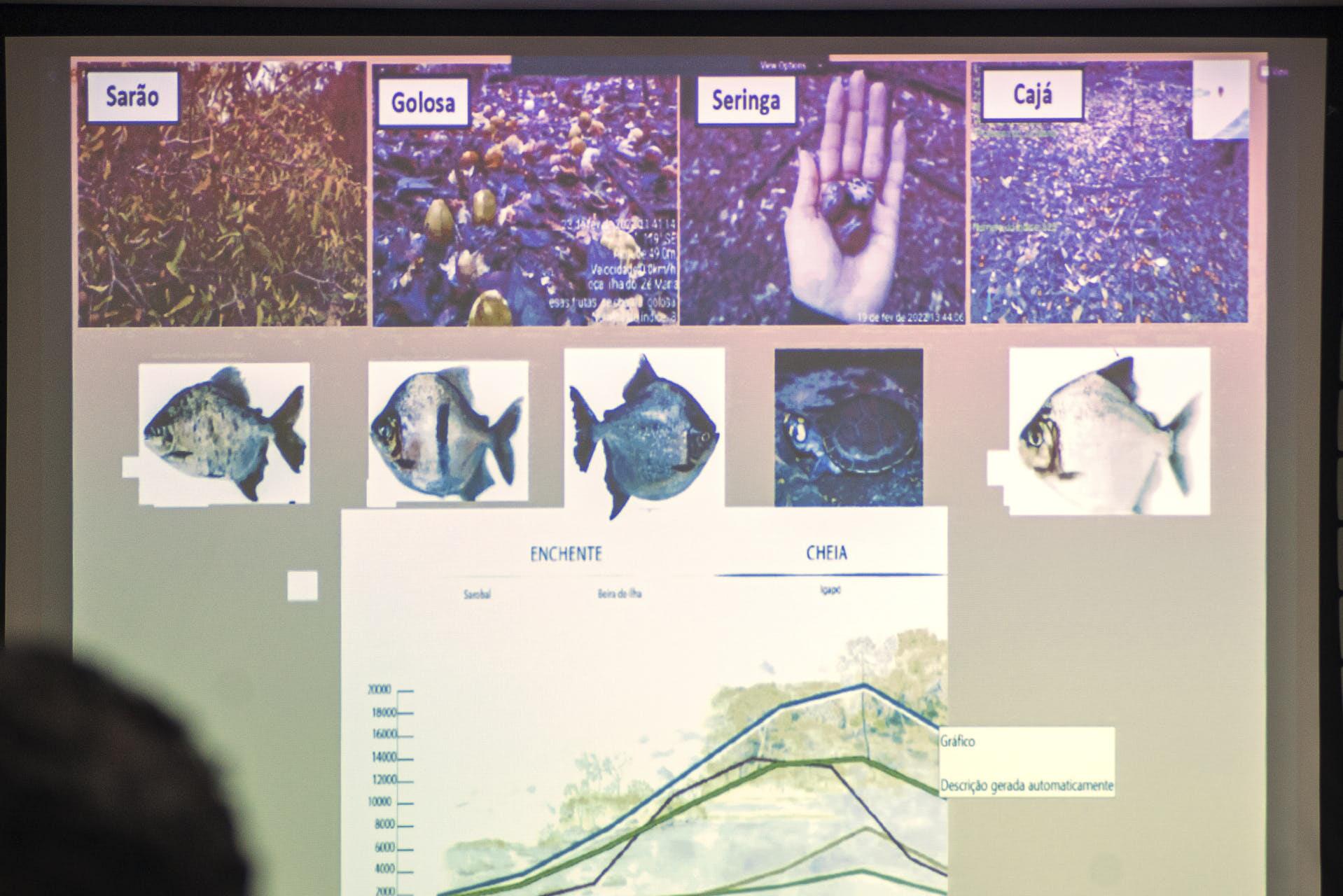

When questioning the quality of the studies produced by Norte Energia, the scientist Juarez Pezzuti, from the Federal University of the State of Pará, caused the audience to fall about laughing. It is worth bearing in mind that without the independent research carried out by the Observatory of the Big Bend of the Xingu, these studies would be the only ones to be presented to Ibama. The researcher then listed a series of experiments that the company conducted in the Big Bend region at high cost, in an attempt to avoid the most important issue, namely that of the sharing of the waters. They were so clearly ineffective that the indigenous people and riverside dweller could not stop laughing. The proposals included the placing of floating rafts imitating natural vegetation so that the fish could feed even without the river flooding. Or hiring people to go past in boats and throw fruit into the water. Or even throwing young fish produced in fish farms to repopulate the Xingu.

“There is vast amount of scientific literature, more than 60 years’ worth of studies on the Amazon rivers’ flood pulse, on the dynamics of flooding in alluvial forests, on the role of fish and turtles, tortoises and terrapins as gardeners (that disperse seeds) of the igapó forests. But this is not taken into account by Norte Energia when it comes to mitigation measures (damage reduction),” said the researcher.

Anthropologist and retired professor from Fluminense Federal University , Tânia Stolze Lima, defined the hydrograph of the Big Bend of the Xingu as Belo Monte’s “origin myth”, which allows the dam to foster a “semantic devastation” in official documents, presenting data and numbers that have no basis whatsoever in reality and taking them as proof of a nonexistent reality.

“This theft of time from the river, the disruption of the Big Bend’s flood pulse, is nothing less than the radical abolition of the millennia-old history of a material and semiotic regime that has been in force in that place and that involves not just human beings, but the other species of non-human life that exist. It is the annihilation of practices of knowledge, economies, and an age-old social philosophy that involves the consistency and conditions of existence of those territories. It was clear here that this does not occur without a devastation of interpersonal relationships, without psychic suffering and without the experience of humiliation and a loss of dignity,” she said. She recalled what Bel Yudjá (Juruna), a leader of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Land, of the Xingu’s Big Bend had said: “The river is our dignity”.

So what now, Ibama?

Even before the decision in relation to the Operating License, Ibama may present an opinion on the urgent and specific issue of the hijacking of the Xingu’s water by Belo Monte. The entity’s president, Rodrigo Agostinho, declared at the end of the seminar that this question is a priority and will be analyzed “with care”. He then faced an outcry from the fisherwoman and researcher Sara Rodrigues, who asked him directly: “What are we going to eat until you do these analyses? Because there are no more fish”.

This question echoed in the auditorium of the Attorney General’s Office and it will have to be answered not just by Agostinho but by a number of other officials in the new government. Funai’s president, Joenia Wapichana, stated she will also be conducting new analyses of what is taking place in the Xingu’s Big Bend and guaranteed that fishing and food security are essential themes. She also announced that, prior to issuing the technical opinion regarding the renewal of the operating license, there will finally be a prior, free and informed consultation with the region’s indigenous peoples, in response to a recommendation by the Federal Public Defender’s Office. “President Lula’s commitment is not just with Roraima,” she guaranteed, referring to the emergency action against the ongoing genocide of the Yanomami people due to illegal mining. The Minister of the Environment, Marina Silva, who had confirmed her presence at the seminar, was unable to attend because she was hospitalized the day before with a suspected viral infection, but the ministry she heads sent representatives and will play a fundamental role in this debate.

Ronaldo Juruna, leader of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Land, was one of the representatives of the indigenous peoples affected by the ongoing catastrophe in the Big Bend of the Xingu – the Yudjá Juruna, Arara and Xikrin, as well as isolated groups. All of them want to know whether the government is going to stop the ecocide caused by Belo Monte. Photo: Matheus Alves/Sumaúma

The authorities’ next steps for the future of the Xingu will have to take into account traditional and indigenous knowledge which has until now been ignored. Among the questions that need to be answered, one stands out and was asked by the Regional Attorney of the Republic, Felício Pontes Jr, who is one of the seminar’s coordinators. He cited the proposal to amend the Rome Statute to include the crime of ecocide, which reads: “For the purposes of this Statute, ecocide shall be understood to mean any illegal or arbitrary act committed with the knowledge that it is highly likely to cause serious, extensive or lasting damage to the environment. “

The question from the three indigenous peoples affected by the ongoing catastrophe in the Big Bend of the Xingu, which is reflected in the anguish that their representatives carried as they left Brasilia and returned to the devastated land where they were born and no longer know if they will be able to live, is: will the government that acted quickly to stop the Yanomami genocide stop the ecocide in the Xingu? Until the answer they urgently need is forthcoming, they will continue to monitor death on the river that has been the life of their ancestors for thousands of years.

Note from Norte Energia S.A.

In response to questions from SUMAÚMA, Belo Monte’s concessionaire sent the following note, via the press office that serves the company, FSB Comunicação:

“Norte Energia, the private enterprise concessionaire of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant, has established an excellent dialogue with the Federal Public Prosecution Office (MPF), which is why it was surprised that it was not invited to take part, with the power to speak, in the seminar “The Future of the Big Bend of the Xingu”, as it is sure that it could have contributed significantly to the debate and to clarify a number of issues raised at the meeting. Norte Energia relishes the transparency of its actions vis-à-vis society and government agencies, and commends the importance of the Federal Public Prosecution Office’s role as defender of the legal system, democracy and inalienable social and individual rights. Notwithstanding this, the topics that were included in the seminar are worthy of a civil lawsuit in the public interest filed by the Office of Federal Prosecution in the municipality of Altamira, in the State of Pará in the Judiciary. Precisely for this reason, and in order to respect and dignify the role of all public institutions, it is understood that they should be treated in the context of their respective processes, a forum in which it is the prerogative of the parties to have their rights to a full defense and adversarial proceedings, as well as the impartiality of the judgment. Regarding any eventual studies in relation to hydrographs carried out independently, Norte Energia has not had access to the data, methodology or detailed analyses of the studies. The company maintains a permanent dialogue and technical monitoring of all issues related to the project, in particular with the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), which is responsible by the legal division of powers to analyze the issues related to environmental licensing. Last, but not least, Norte Energia reaffirms its commitment to transparency, respect for people and the environment, and to the sustainable development of the region in which the hydroelectric plant is located, whilst at the same stressing Belo Monte’s strategic importance to the country’s energy security.”

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Raimundo da Cruz e Silva, a riverbank dweller, fisherman and writer, steers his canoe along the Big Bend of the Xingu. At the seminar, he said: ‘Belo Monte was a catastrophe foretold, now it is a catastrophe experienced’. Photo: Soll Sousa/SUMAÚMA