Alice Oliveira, 13, and Esthefany Leal, 12, were born and live in the Vila Praia Alta Community, along the banks of the Tocantins River, in the state of Pará. They know every inch of the area. They know how much care is needed to catch a peacock bass, the fish that are usually found in the lakes that form in the rocky outcrops along the river. They have learned that fishing activities follow the moon’s rhythm and the best place for planting is the floodplains, which are fertile areas that form when the river recedes.

They also tell stories they’ve heard from their elders, like the one about Nego d’Água – an entity they say inhabits the depths of Pedral do Lourenção, a set of rocky formations on that stretch of the Tocantins River. This is where he approaches fishers and asks for fish. If he is denied, an angry Nego d’Água will overturn their vessel. Alice gets excited when talking about the creature, but her tone soon shifts. Enthusiasm turns to sadness: “If they really do this project, he’ll have to find somewhere else to live. If there’s time, that is.” Their concern regards not only the story their ancestors tell about this entity – it also has to do with the concrete threat lurking around their houses, their community, the river and its animals and, ultimately, their very existence.

Praia Alta residents Alice Oliveira and Esthefany Leal look out onto the Tocantins River: past, present and future are at stake. Photo: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

On May 26, Brazil’s environmental agency, Ibama, granted an installation license authorizing the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure to begin what they call the “clearance” of the rocky outcrop known as Pedral do Lourenção – a project that will blow up these rock formations to then remove them, widening and deepening the river so bigger boats can pass through. It is part of a project to expand the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway, a river route aimed at expanding capacity to ship soybeans through Pará’s ports, allowing this product, which is a major driver of Amazon deforestation, to more easily reach other countries.

Ibama’s decision is being questioned. The first preliminary license for the works to be done on the waterway was issued in 2022 and is being contested by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, which feels the impacts have yet to be fully assessed. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office had already asked for the preliminary license to be voided and it is now also contesting the installation license, with the understanding that it violates an effective ruling by the courts. In response to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office’s first suit, the courts did not void the preliminary license, but they did prohibit licensing of other areas until some of the environmental requirements are met (see below).

SUMAÚMA traveled the Tocantins River over the last few months and visited Pedral do Lourenção. We heard stories of the many lives that inhabit the river and whose existence is now threatened.

‘If there’s no outcrop, there’s no fish’

The children of Vila Praia Alta learn about how the rocky outcrop inherited its name from a very brave man named Lourenço who lived in those parts. They say he drowned while bathing in a waterfall. He was called Lourenção – and that was how he remained in the memory and words of the communities. Over time, when technical studies started to be done in the region, the name of the place began to appear on official documents as Pedral do Lourenço, literally Lourenço’s outcrop.

Out of respect for the communities we talked to for this story, SUMAÚMA is providing the spelling used by the authorities, but notes what those who live there call it Pedral do Lourenção.

For the Ribeirinhos, blowing up the rocky outcrop and widening the river spells death for countless lives. “If there’s no outcrop, there’s no fish, no shrimp, no turtles, no nothing,” Alice says.

Erlan Moraes do Nascimento, 30, agrees. He leads the Vila Praia Alta Extractivist Ribeirinho and Small Family Farmers Community Association and he was born in the community where he lives today. His father has been there for over six decades. Erlan is a fisher and supports his family with what the Tocantins provides him: fish, fertile land, peace. “It’s a calm that you can’t even explain. I’ve had the chance to leave, I even went into the Army, for nine years I lived in Marabá. But I always intended to return.”

In the community, he plants cupuaçu, cassava, corn, and pineapple. In the summer, he plants on the floodplains. “The earth is good because the river brings so much. When the water recedes, then it’s time to plant. I learned from my father.”

Erlan Moraes, Sara Fernandes and their son Paulo, in Praia Alta: the community will be affected by the explosion of Pedral do Lourenção. Photo: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

Erlan and his neighbors are losing sleep over the news about the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway. “Barges come through here every once in a while. Last month one got stuck there in front for almost a month, filled with soy. They took the wrong channel. If it’s like this now, imagine later.”

Erlan says that for someone who has known the riverbed since childhood, the waterway proposal makes no sense: “In the summer there are spots in the river that don’t even reach 100 meters deep. And these are the spots where we fish. Now tell me: how can they say it won’t cause problems? They’re talking about removing the rocks. But the rocks hold the sandbanks too. Can you imagine the damage?”

Contested licenses

Explosion of the rocky outcrop is one of the most contested stages of the waterway project, since it is considered a sanctuary for fishers, scholars, and traditional communities. The National Department of Transportation Infrastructure formally recognizes just 11 communities as being directly affected. Yet according to local leaders, at least 23 make their living from fishing, extractivism, and subsistence farming in the areas that would be impacted.

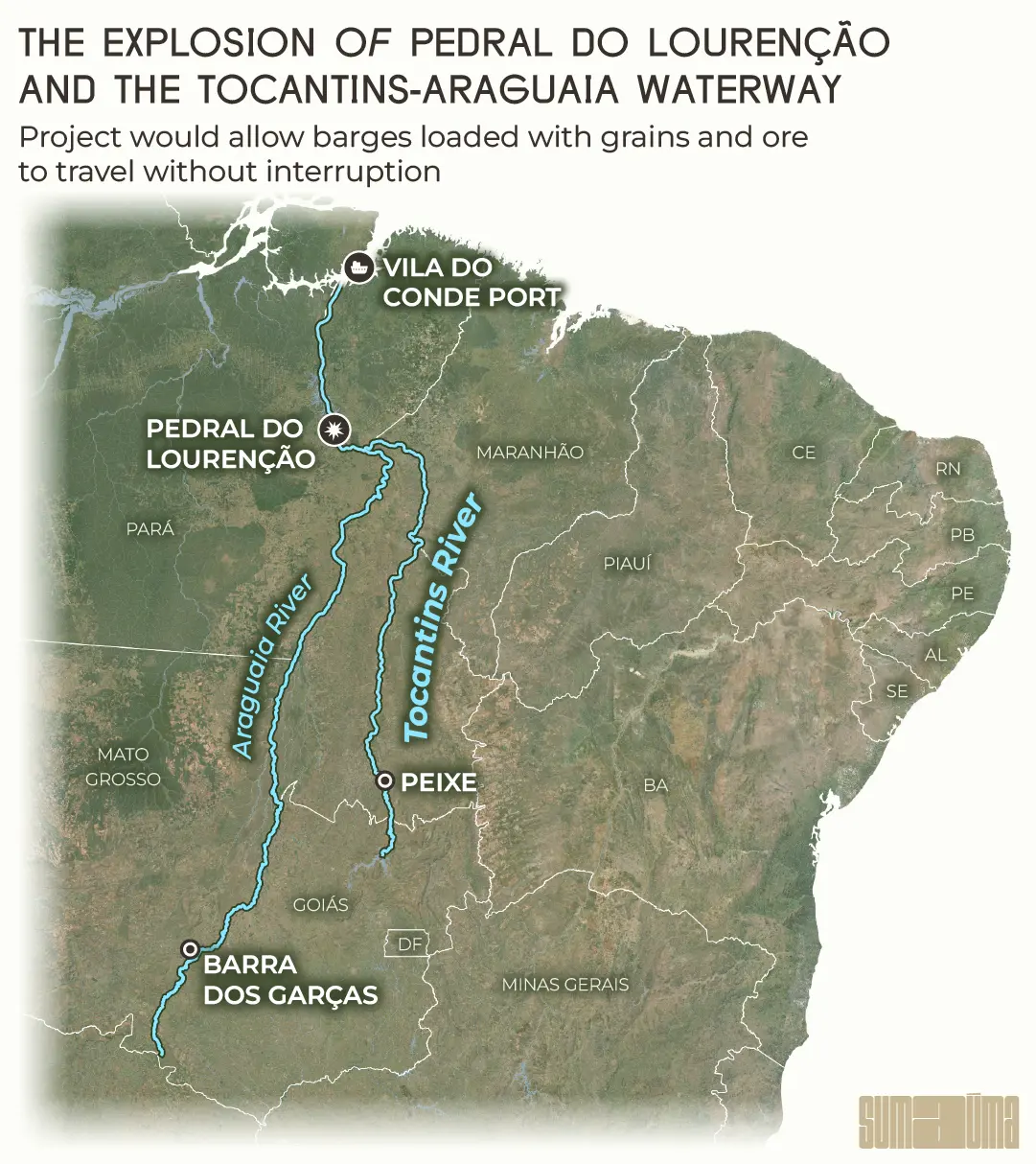

Blowing up the rocky outcrop is seen as a strategic step for the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway, a logistics corridor nearly 3,000 kilometers long that would connect the cities of both Barra do Garças, Mato Grosso, and Peixe, Tocantins, to the Port of Vila do Conde, in Barcarena, near Belém, Pará. The rivers are navigable today, but not along every stretch, as some places lack sufficient depth. The explosion would create an uninterrupted journey, even during dry months, for barges laden with grains and ore.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

The project will open a channel 70 to 160 meters wide in the area of Pedral do Lourenço. The license granted by Ibama mentions using dynamite along a 35-kilometer stretch between Tucuruí and Marabá, Pará. The National Department of Transportation Infrastructure is talking about 43 kilometers of rapids.

Since 2016, the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway project has been part of the Investment Partners Program, created during the Michel Temer administration. The program gave the waterway “national priority” status and the project began to progress.

On October 11, 2022, Ibama granted preliminary license no. 676/2022 to the set of works needed to build the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway. The license includes 49 conditions, according to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office says there was no prior, free and informed consultation of the communities affected, a right guaranteed by ILO Convention 169. In the prosecutors’ view, the consultation needs to happen during the planning phase, before issuing any license. That was not what happened.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office also says that a court ruling reiterated the need to meet these conditions. According to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, requirements that have not been fulfilled include: in-depth studies on the region’s aquatic wildlife; an analysis of the accumulated impacts caused by the Tucuruí Dam; and adoption of concrete measures to mitigate the project’s ecological and social damages.

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office asked that the preliminary license be voided. It alleged a series of irregularities, such as a failure to consult traditional communities and a precarious strategic environmental assessment of the entire waterway and of risks to biodiversity, especially fish. The region is home to what the Ribeirinhos call resident fish species, like armored catfish, which could cease to exist if their residence is blown to pieces.

An aside: days before the environmental agency issued an installation license for the outcrop, the Senate passed a bill creating the General Environmental Licensing Act, Bill 2159/2021, which became known as the Devastation Bill. If this bill passes the Chamber of Deputies, it will once and for all authorize projects like the one on the Tocantins River using a lightning fast licensing process. If the Devastation Bill were already in effect, the rocks sustaining this stretch of the Tocantins River could have been destroyed years ago.

Pedral do Lourenção and life at a standstill: the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has sued to block the project’s license. Photo: Antonio Cavalcante/Ascom Setran

On July 4, 2024, the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure moved forward, solely requesting an installation license for the Pedral do Lourenço area. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office is objecting based on the non-fulfillment of the license conditions. “The conditions aren’t just bureaucratic. They’re tools to protect human and non-human lives,” says federal prosecutor Rafael Martins, who helped to write the civil public action asking to void the preliminary license. He and his colleague, prosecutor Felício Pontes Júnior, argue that allowing the project to go on without meeting these obligations is akin to ripping up environmental legislation.

On February 5, 2025, justice José Airton de Aguiar Portela, of the 9th Federal Court of Pará, handed down a ruling that upheld the preliminary license, but that forbade new licenses from being issued for other stretches of the waterway until the Indigenous, Quilombola and Ribeirinho people are consulted and included in programs for compensation, monitoring of fishing, and social monitoring.

Now the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office is looking at legal alternatives to continue the suit that asks to suspend the preliminary license and, consequently, the installation license granted afterward.

The prosecutors are also calling attention to an increasingly common practice in large projects: the breaking apart of environmental licensing. Because the project is submitted in parts, the developers are able to obtain partial licenses while the whole of damages is never fully assessed. As the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office sees it, this strategy embeds an original irregularity, since it breaks apart the impacts as if they were not related to each other. In the case of the waterway, this means moving forward with the detonation of rocks and excavations even before understanding what could disappear along with them. And this compromises a full assessment of the environmental and social impacts.

Humans and more-than-humans: Pedral do Lourenção is home to shrimp, turtles, resident fish and children who grew up with the story of Nego d’Água. Photos: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

The National Department of Transportation Infrastructure and Ibama comment

When asked by SUMAÚMA, the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure disassociated the rocky outcrop project from the group of waterway projects: “The National Department of Transportation Infrastructure is conducting licensure of the Araguaia-Tocantins Waterway along with Ibama. The environmental license being considered regards Dredging and Clearance works on the Tocantins River Waterway, specifically in the stretch between Marabá and Baião, in the state of Pará.”

The National Department of Transportation Infrastructure also claims to have met the preliminary license conditions. “It is crucial to understand that, in this phase, the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure has met all Preliminary License conditions related directly to clearance works,” reads the text sent to SUMAÚMA.

The department argues that just 11 of the region’s 23 communities are in the project’s direct area of influence: “Some of the 23 communities mentioned by local leaders are located along Tucuruí Lake, where there will be no direct intervention by the project.” However, the statement ignores the interdependent and systemic nature of the river and the lifeforms dependent upon it. It also fails to recognize that artisanal fishing, fish reproduction and the Ribeirinho way of life depend precisely on the rocky outcrops that will be removed.

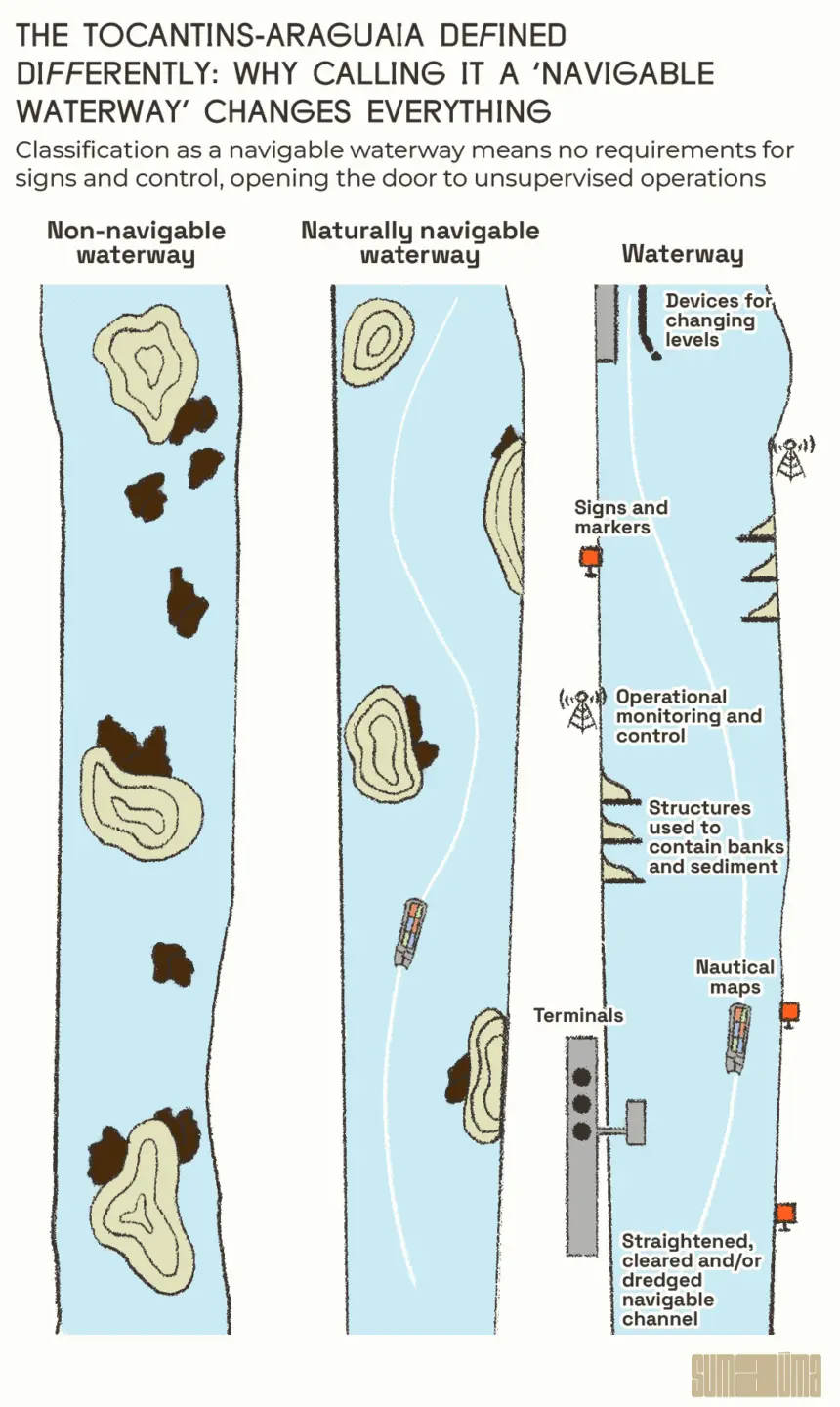

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

SUMAÚMA reached out to the federal environmental agency, Ibama, on May 15 and received a response on May 22 where the agency said it had received a notice from the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure stating the conditions had been met, but that additional information was nevertheless requested. According to Ibama, there was an on-going decision process. The agency stressed the installation license only concerns the clearance of Pedral do Lourenço and does not cover the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway: “The information submitted indicates that the project being licensed in the area could operate independent of the licensing for other areas. Ibama has no information that the project will be extended.”

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office contests this. It says the fact that licensing only considers the impact of works on the rocky outcrop and not all of the waterway projects makes clear that the communities are being ignored in the process, as well as the fact that “the end goal of the project is implementation of the Araguaia-Tocantins Waterway.”

Regarding the number of communities potentially impacted, Ibama said there was no formal request “for expansion of the area of influence to include other communities.” In relation to a consultation of the affected communities, the agency pointed to five public hearings that were held, but acknowledged they are different from the free, prior and informed consultations required by the ILO. And, despite claims of being willing to collaborate in fulfilling the ILO’s recommendation, the environmental agency stressed that it is not the role of the licensing agency – Ibama, in this case – to guarantee these consultations are held.

A multi-administration project

The Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway project is not the work of just one administration. It has been cooking for over three decades, passing from one party’s administration to the next.

The first attempt to get the waterway up and running dates back to the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Social Democratic Party) administration in the 1990s. The project became an issue again under Workers’ Party administrations and gained new life when party member Dilma Rousseff was in office. Under the Michel Temer administration, Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement), the national integration minister at the time, signed a contract for studies and projects to clear Pedral do Lourenço.

In April 2023, Helder, now the governor of Pará, showed support for the waterway during an event with executives in Marabá and he has strengthened his offensive within the federal government. The federal government plans to tap its New Accelerated Growth Program and allocate around R$ 1 billion to clearing the outcrop.

On May 26, 2025, the governor gleefully took to social media to comment on the license from Ibama. “I want to celebrate this moment. I’ve just spoken to [transportation] minister Renan Filho and in the coming days we’ll be in Itupiranga together, in this whole region, to sign the service order to start work on removing the rocks from the Lourenção region and ensure the river can be navigable with barges, with vessels, with production being able to use our rivers.”

A barge on the Tocantins River: Pará’s governor, Helder Barbalho, is one supporter of the Tocantins-Araguaia Waterway. Photos: Ronaldo Macena/Arquivo pessoal e Pablo Porciúncula/AFP

In a statement sent to SUMAÚMA, the ministry of ports and airports said the waterway remains a priority and the ministry is “reinforcing its commitment to current environmental legislation, assuring that all stages of the development follow legal and technical processes, with constant dialog with the control and oversight agencies.” The ministry sees the waterway as a transport alternative that is “more sustainable, less costly and has less environmental impact,” and as the method of transport with the most potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It would also lead to lower costs and would relieve highway infrastructure, the ministry says.

A silent farewell to turtles and fish

Cristiane Vieira da Cunha, a professor with the School of Rural Education at the Federal University of South and Southeast Pará, is familiar with the rocky outcrop and its surroundings. She coordinates monitoring of fish and management of chelonians, the scientific name for turtles, terrapins and tortoises, in at least ten communities. These include the arrau turtle and the yellow-spotted river turtle.

Families make their living from artisanal fishing, extractivism and subsistence farming – activities that, in the professor’s opinion, were never even considered in the technical studies that served as the basis for licensing the project. “The plan for the navigation channel overlaps the exact spot where there are fishing areas and there are beaches where chelonians lay their eggs,” Cristiane explains. “Even so, there is no in loco survey of aquatic wildlife. The references used are secondary. The experience of fishers, of the women who manage the nests, everything was ignored.”

‘Everything was ignored:’ Prof. Cristiane Vieira da Cunha coordinates chelonian monitoring projects in the communities. Photo: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

From 2017 to 2020, monitoring shows 4,977 fisheries and a catch of nearly 200 metric tons of fish in the regions now at risk. The revenue that went directly to families was over R$ 670,000 during this period. In the data found by the study, communities like Vila Tauiry, Santo Antonino, Cajazeiras, Pimenteira and Praia Alta top the list in fish volumes and resources generated. Yet monitoring of fishing in these communities isn’t on the radar for officials.

Since 2017, the families have been collaborating on a community chelonian management project stretching from Marabá to Tucuruí Lake, which has helped 218,000 baby arrau turtles and yellow-spotted river turtles return to the river, where they find protection from human and natural predators.

They would be protected. The beaches where these turtles lay their eggs will also be affected by works to clear the outcrop.

There is an elongated fish, around 18 centimeters long, with skin that varies between gold, yellow and metallic green tones, who lives in the rocky outcrop. Its large eyes keep a close watch over its surroundings, while its downturned mouth routinely turns grains of sand and small stones over to find food. Its scientific name, Retroculus lapidifer, holds a clue to one of its habits: lapidifer means “bearer of rocks,” a reference to its rare behavior of using stones to build nests where it cares for its offspring. The species is endemic to the Tocantins-Araguaia basin; in other words, it is found in no other region of the world. It depends on highly oxygenated environments that have constantly flowing water and rocky riverbeds.

Researcher Alberto Akama, a professor at the Emílio Goeldi Museum in Belém, Pará, explains that some fish depend exclusively on the deepest and rockiest stretches of the Tocantins to survive. That is the case of the gilded catfish, a fish that finds shelter in the rocks; of the redtail catfish that seeks refuge in stony underwater terrain; and of giant plecos, like Acanthicus hystrix and Pseudacanthicus, which can grow to almost one meter long and which only live at depths of under 15 meters. These are what the Ribeirinhos call the resident fish species that live in the rocky outcrop.

An artisanal fisher in Pedral do Lourenção: communities make a living from fishing, extractivism and subsistence farming. Photo: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

These animals do not migrate, they do not come up to the surface, and they have no other possible home: if the rocks are blown up, they will disappear. They are an invisible species to anyone who has never plunged the depths of the outcrop, but they sustain the complexity of the ecosystem in Tocantins. “There is no way for these fish to go elsewhere,” Akama says. “If these rocks are removed, they’ll simply disappear. They’re species that nobody sees, but they’ve been there for thousands of years.” Some of these species were never even cataloged – and they run the risk of disappearing before we even know their names.

The professor is concerned about the license. “It offers no guarantee whatsoever for the species living there. The mitigation measures are weak, almost symbolic, and even so, we don’t know whether they’ll actually be implemented. The monitoring actions proposed fall far short of what is needed. We would, for example, need to have real-time monitoring of what happens to the wildlife when the rocks are blown up. But this wasn’t even considered.”

Akama also repeats a warning made by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office: the lack of a prior, free and informed consultation of the communities. “I won’t go into the legal merits, but from talking to residents it’s obvious that the process was remiss. And there is a technical detail that few people are talking about: the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure is now saying that this is no longer about a waterway, but a ‘navigable waterway.’ This changes everything. [A waterway, as defined by the National Waterway Transportation Agency, requires standardized vessels, signage and control.] On a navigable waterway, there is no control: as many barges can pass through as would like, whenever they like. And no one knows how they’ll operate. Nobody answers for this. This license is premature. It was ill thought out. And, honestly, it doesn’t seem to have been issued with the intent to preserve the environment or the species that are at risk.”

According to the National Department of Transportation Infrastructure, Pedral do Lourenço is a bottleneck that needs blowing up. For agribusiness, it’s a chance to turn a river into a road. Yet for those who live there, Pedral do Lourenção is a refuge, it is sustenance, and it is home. It is the place where the arrau turtles, the resident fish, the children who learn to fish, the elders who tell the stories of the legends and of Nego d’Água, where everything is part of the same network of life. Blowing up the outcrop means tearing this fabric forever.

A child at Pedral do Lourenção: authorities hold the future of those who live on the banks of the Tocantins in their hands. Photo: Márcio Nagano/SUMAÚMA

Report and text: Catarina Barbosa

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Art Editor: Cacao Sousa

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum