The sound of hundreds of maracas being shaken by Indigenous hands in the Praça dos Três Poderes multiplies as it echoes off the windows at the Palácio do Planalto, the seat of executive power in Brazil. The modernist building designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer is less than 50 meters away, but a fence barricade and dozens of police officers keep them from going close. There, on the evening of Thursday, April 25, a meeting is being held between President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party) and 40 leaders of Brazil’s original peoples.

It is a very different scene from a year ago. In 2023, the president spoke at the closing ceremony of the largest meeting of Indigenous peoples in Brazil, the Free Land Camp, where he signed documents to approve demarcation of six territories. Despite the leaders and the thousands in attendance expecting this number to be 14, Lula received thunderous applause and his name was chanted. In 2024, however, the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil did not invite him to speak at its annual event in Brasília. It demanded that the president receive Indigenous leaders at his Palácio do Planalto office. They wanted to force Lula to announce progress. Instead, the president wanted a meeting held far from the eyes, ears, and mouths of the over 8,000 Indigenous people who had traveled to the capital.

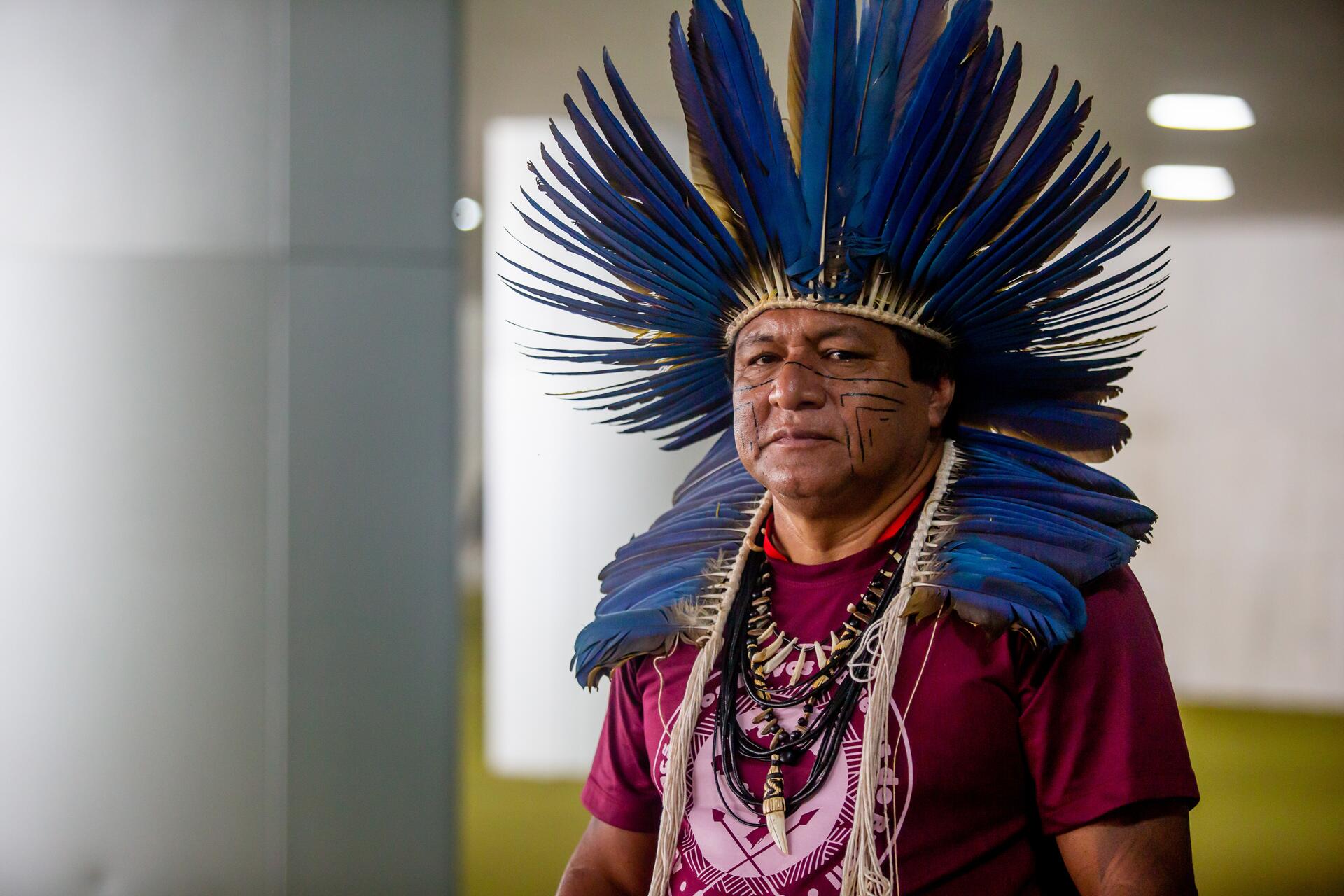

The 20th edition of the Free Land Camp, which ended on Friday, April 26, was marked by extremes. The annual march of original peoples to Brasília had never been so numerous or gathered so many different peoples – over 200 out of the 305 peoples in Brazil attended, according to the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil. They debated public policies, shed light on attacks and violence against their territories, challenged the authorities, sang, danced, and exhibited the vibrant diversity of languages and cultures that Brazil insists on ignoring.

Indígenas de mais de 200 povos se preparam para sair em caminhada à Praça dos Três Poderes

On the other hand, they left the capital frustrated with yet another postponement in demarcating their traditional territories, a mandate of the Brazilian Constitution that should have been fulfilled in 1993 – which means it is at least 30 years overdue. They also found that they could lose a battle in the Brazilian Supreme Court that had already been considered as won: the fight over the historic cut-off point, a move to restrict Indigenous demarcation claims to territories they were occupying or disputing on October 5, 1988, the date of the Constitution’s enactment. This prevents original peoples from being entitled to territories from which they were expelled between the time of the Portuguese invasion in 1500, and the year 1988.

The Supreme Court has already ruled that the historic cut-off point is unconstitutional. However, on Monday, April 22, a day dedicated to Mother Earth and the first day of the Free Land Camp, Supreme Court Justice Gilmar Mendes issued an individual ruling reopening this question, along with another threat: mining in Indigenous territories.

This cunning maneuver signals a possible step back by Brazil’s Supreme Court. This court was essential to blocking an unconstitutional power grab by former, far-right, president Jair Bolsonaro, but the court and some of its justices have been subject to major attacks by Congress, since the issues the legislature is writing into law end up being overturned in the courts because of their flagrant unconstitutionality. In recent weeks, super-billionaire Elon Musk has joined the attacks, ramping up and amplifying the discourse of “censure” and attacks on “freedom” used by the extreme right in Brazil and around the world. Musk has shown support on X for Jair Bolsonaro and those involved in the attempted coup on January 8, 2023, using the social media network to make personal attacks against the court and at least one of its justices.

When he created the Indigenous Peoples Ministry at the start of his third term as president, Lula raised hopes that the Indigenous people’s demands would finally be answered in Brasília. Yet the ministry still needs to be made much stronger to make a difference for the original populations who have been fighting for justice for centuries. The ministry’s mere existence has emotions running high among the Indigenous people’s enemies, represented in the national congress by the extremely powerful Agricultural Parliamentary Front, lobbying for the interests of agrochemical and ultra-processed product manufacturers, large landowners exporting soy, corn and cotton, and beef cattle farmers.

On the floor of the House of Representatives, an indigenous woman explains that demarcations conserve forests

These are people who also run ministries under the Lula administration and have easy access to most of the Supreme Court’s justices. Faced with the strength of their enemies, the Indigenous people seem to be at an impasse: things are bad with Lula and the government, but without Lula it would be much worse. It is hard to image that the Indigenous issue can indeed move forward without the support and involvement of those in Brazilian society who care about the climate emergency and the urgent need to conserve what still remains of Brazil’s natural biomes.

To understand the impasse, it is necessary to travel back in time a few days.

Lula and Sonia Guajajara during a ceremony at the Ministry of Justice. Photo: Gabriela Biló/Folhapress

April 18, 2024, Justice Ministry

Leaders are palpably irritated at the close of the first meeting of the National Council on Indigenous Policy. The Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil hoped that Lula would certify – that is, sign a document concluding the demarcation processes – six lands. They are part of a group of 14 territories which as of January 1, 2023 only required a presidential signature to move forward. Lula had committed to taking care of these territories within the first 100 days of his third administration. Yet he had only signed eight certifications in 2023. Six were left.

A few hours earlier, Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil coordinators learned that only two would be certified. “I know that you all are somewhat apprehensive, because you thought you would have news of six Indigenous Territories signings,” Lula admitted. And he ventured a justification. “We have a problem. Some territories are occupied by farmers. Others, by normal people, probably as poor as we are. Some governors have asked for time to figure out how to remove these people. And we’re providing this time.”

As soon as the event was over, leaders held an emergency meeting. “If there’s interference from the governors, we’re worried. We’re encountering another political barrier to demarcation of the territories,” said Indigenous attorney Dinamam Tuxá, the executive coordinator of the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil.

Warriors from the Xikrin people of Catete and their children in Brasilia

Monday, April 22, 2024, Free Land Camp

“I’d rather have an enemy who doesn’t pat me on the back than an enemy who does, but does nothing for me,” Kretã Kaingang tells an audience of a few journalists in one of the camp tents. Kretã is a short, heavy-set man with a severe expression on his face.

“In the fight for land, 70% of those living in tarp [homes] are children. They are on the front line,” Kretã continues.

Like many Indigenous people, his life has been marked by successive family tragedies. His father, ngelo Kretã, was the first Indigenous public official elected in Brazil. He died in 1980, during the business-military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985, in a car crash caused by an ambush by loggers. One of his daughters, Angélica, who would go with him to marches and camps, fighting for demarcation, died of undisclosed causes in February of this year.

‘I’d rather have an enemy who doesn’t pat me on the back than an enemy who does, but does nothing for me,’ tells Kretã Kaingang

Kretã is outraged by another delay in certifying two Indigenous Territories located in Santa Catarina, a state in southern Brazil where 76% of the votes in the 2018 election went to the extreme-right candidate Jair Bolsonaro and which is currently run by a staunch ally of the former president. “We want these demarcations because it is a racist, fascist state that opposes the Indigenous peoples. It’s a question of honor,” the Indigenous leader says.

In response to Lula’s speech days earlier, the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil released its letter of demands early: “While historic cut-off points are being discussed and more time is being given to politicians, our lands and territories remain under threat, our lives and cultures are at risk, and our communities face a constant struggle for survival.”

That night, however, the attack would come from a different building in the Praça dos Três Poderes.

Indigenous people protest against historic cut-off point and mining

Mining combined with the historic cut-off point

In a ruling issued on the night of April 22, Federal Supreme Court Justice Gilmar Mendes stayed three actions challenging the constitutionality of Law 14.701, through which Brazil’s Congress established a historic cut-off point for demarcations, even after the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional.

Mendes admitted that “apparently, many of its provisions can be read with an opposite sense of the understanding that this Court has reached [in the ruling on the historic cut-off point].” Even so, he did not suspend the law. And he inserted his ruling into another legal proceeding where the Progressives party is asking the Supreme Court to interpret a passage in the Constitution that could authorize mining in Indigenous Territories. The Progressives include many of Brazil’s right-wing politicians, such as the powerful president of the lower house of Congress, Arthur Lira, and the leader of the Agricultural Parliamentary Front, Pedro Lupion.

In practice, the justice wedged the topic of mining in Indigenous territories into the discussion on the historic cut-off point. He also ordered a “conciliation” chamber be set up to mediate an agreement on both issues. This opened the possibility that an activity with significant environmental impact could invade the original peoples’ territories, which would raise the risk to even more alarming levels that the Amazon will reach the point of no return in the coming years.

From the Praça dos Três Poderes, Indigenous people observe the Palácio do Planalto

The legal coordinator of the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, attorney Mauricio Terena, points to the cross contamination of politics and the courts. “The action filed by the Progressives party isn’t about the historic cut-off point. The connection [between the two topics] doesn’t exist. This is a political trial dressed up in legal arguments.”

Mauricio continues: “Our challenge is to understand what is happening. The Indigenous people don’t lunch with the Supreme Court justices. And sometimes the decisions seem to be made at lunches like this. We are already starting the negotiation at a disadvantage.”

‘The historic cut-off point is the death of our people’, says Alberto Terena

When they do gain access to the justices, the Indigenous people are shown worrisome signs. On the evening of Tuesday, April 23, the court’s chief justice, Luís Roberto Barroso, met with the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil’s legal coordinator and a delegation of leaders. “Barroso signaled to the Indigenous movement that the Supreme Court will no longer tangle with Congress on minority issues,” Mauricio said.

Barroso told SUMAÚMA that the September 2023 ruling on the historic cut-off point was not rendered in a hearing “with abstract and general understanding.” “This will only be done in the direct hearing on the challenges to constitutionality in relation to the historic cut-off point.” Mauricio feels the conclusion is obvious: “The Federal Supreme Court could take back what it already said.”

Lula and Sonia Guajajara at the beginning of the meeting with Indigenous leaders at the Palácio do Planalto

One day before the Free Land Camp started, the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper reported that Lula, aiming to achieve economic growth, wants to force mining companies to bolster their production in Brazil. On April 15, Gilmar Mendes welcomed Lula and Supreme Court justices Flávio Dino, Cristiano Zanin (both appointed by Lula in 2023), and Alexandre de Moraes to his home. Days later, Zanin welcomed an Indigenous delegation to his office. He silently listened to their arguments on the historic cut-off point. When he spoke, he asked about mining in Indigenous territory.

Through the Supreme Court’s press office, SUMAÚMA asked Gilmar Mendes to comment on Indigenous criticism of his ruling. A response was not returned.

Thursday, April 25, Palácio do Planalto

At the end of a meeting at the president’s Palácio do Planalto office, Sonia Guajajara came down to speak with reporters. She was accompanied by Márcio Macêdo, the head of the Office of the President’s General Secretary. Macêdo said Lula had committed to creating a task force to resolve the “legal and political” problems stalling demarcations When asked why the government took a year and half to do this – the situation of territories where demarcation has not yet been certified has been common knowledge since 2022 – Macêdo did not respond.

The caciques Valdecir Kaingang and Anibal Potiguara went to Brasília, but the homologation of their lands remained a promise

At the end of the Free Land Camp, the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil published an “urgent statement” addressed to the three branches of federal government. “The deliberate decision by government authorities to suspend the demarcation of Indigenous territories and apply Law 14.701 is equal to a DECLARATION OF WAR against our peoples and territories,” the document reads. There is also a message for those who insist on ignoring the climate emergency and the need to conserve rivers and forests. “We are concerned about the cowardice of those who try to tame untamable time and seek to profit off of our deaths. THERE IS NO MORE TIME FOR YOU!”

Marcha do Acampamento Terra Livre, em 2024, sob o sol forte do outono brasiliense

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editor: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Chief reporter: Malu Delgado

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Coordination of editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum