“You, humans, have this curious habit of naming beings. River. I don’t call myself River. Some know me by the cloudiness of my waters. Others, by the subtle motion of my waves. I call myself so many things. It’s in the silent comings and goings of my current that fish listen to me. Close your eyes and try to hear me too. I can still scream, weep. I just don’t know for how much longer”

The first time the Paraguay River spoke to me was in a dream, in the middle of a stifling night in mid-September in the town of Cáceres, a municipality located in the state of Mato Grosso, where the biomes of the Amazon, Cerrado, and Pantanal coexist. I still hadn’t learned to listen to it with my eyes open. I had arrived a few days earlier, with the goal of understanding why the waterway edging a city of ninety thousand people next to Bolivia, had recently turned into the epicenter of a legal dispute without precedent in Brazil.

In July of 2023, the Paraguay River, and all the other more-than-human beings of the city, had been given the status of legal persons. Now included in the law, they were protected for their own sake, and not only for their utility to humanity. But in a world where humans think they’re the only people, these rights were quickly revoked.

With a length of more than 1,600 miles, the Paraguay River is born in the town of Alto Paraguai, Mato Grosso, and stretches through Mato Grosso do Sul, Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina, tearing through borders invented by humans. It looks unassuming. It has a calm, often flat surface and is often brownish in color, so it gets mistaken for other, smaller waterways. You must slip outside of time and stand on its banks bordering the Amazon region, as it brings water and life to the Pantanal, so each one of your senses is heightened by its vigor. For the River to introduce itself, you must smell it. The odor is sometimes of wet grass. But it can also be of clay – so intense that while penetrating your nose, it leaves a bitter taste in your mouth. Some of its inhabitants, like the Pacu Fish, retain this aroma in their entrails

You must look at it through the lens of its sharp curves, each bend sheltering an infinity of plant-people, animal-people, fungus-people, bacteria-people – lives only made possible because of its flooding cycle. You must listen to it through the sound of its birds, mingling the low grunts of Tuiuiús with the sharp whistles of Spoonbills. And through the stories and legends of its Indigenous peoples and its traditional riverside forest communities of Ribeirinhos, stitched together by memories connected to the seasons, marked by periods of flood and drought that for millennia dictated the rhythm of the place. You must allow yourself to be touched by the cheerful movement of the Aguapés, aquatic plants emerging now and then from the water in the shape of a bouquet, as though the River was giving a welcome present to those who can see it. When we can finally understand the River, we become currents. And when we become currents, the fight for its right to be River makes complete sense. It transforms into a fight for the right of humans and more-than-humans to be Life.

Among the River’s various languages: the law

“Some time ago, I bled. Everything around me became fire. A thick, opaque liquid poisoned my currents and I overflowed with suffering. I dressed in ashes, suffocating lives around me. I thought I would recover, but even now you can find on me the scars of that and so many other tragedies. When the ashes mixed with my flow, my lament echoed in the silence of wounded Nature”

The River speaks, feels, and also weeps. It is we who must learn to listen. For those born currents, like the Indigenous and Ribeirinhos, the dialogue with the River is part of daily life. Vanda Aparecida dos Santos, a Ribeirinha-current who dedicates her life to the protection of these waters, remembers the first time she heard the weeping

Vanda Aparecida dos Santos listens to the weeping of the River, who she talks with daily

It was mid-July of 2020. The Pantanal was suffering the worst wildfire in its history, a criminally set fire consuming around 26% of the biome. Around five in the morning, Vanda was woken by the deafening silence of the birds. “Something was very strange. We’re always hearing the River talk through the song of its Nature, through the force of its water. This time, it had silenced one of its most beautiful conversations. I quickly understood it was the River weeping, begging for help. It was the life of the River dying in front of us.” The fire had not yet reached Vanda’s house, on the banks of a branch of the Paraguay, but the River’s call for help had.

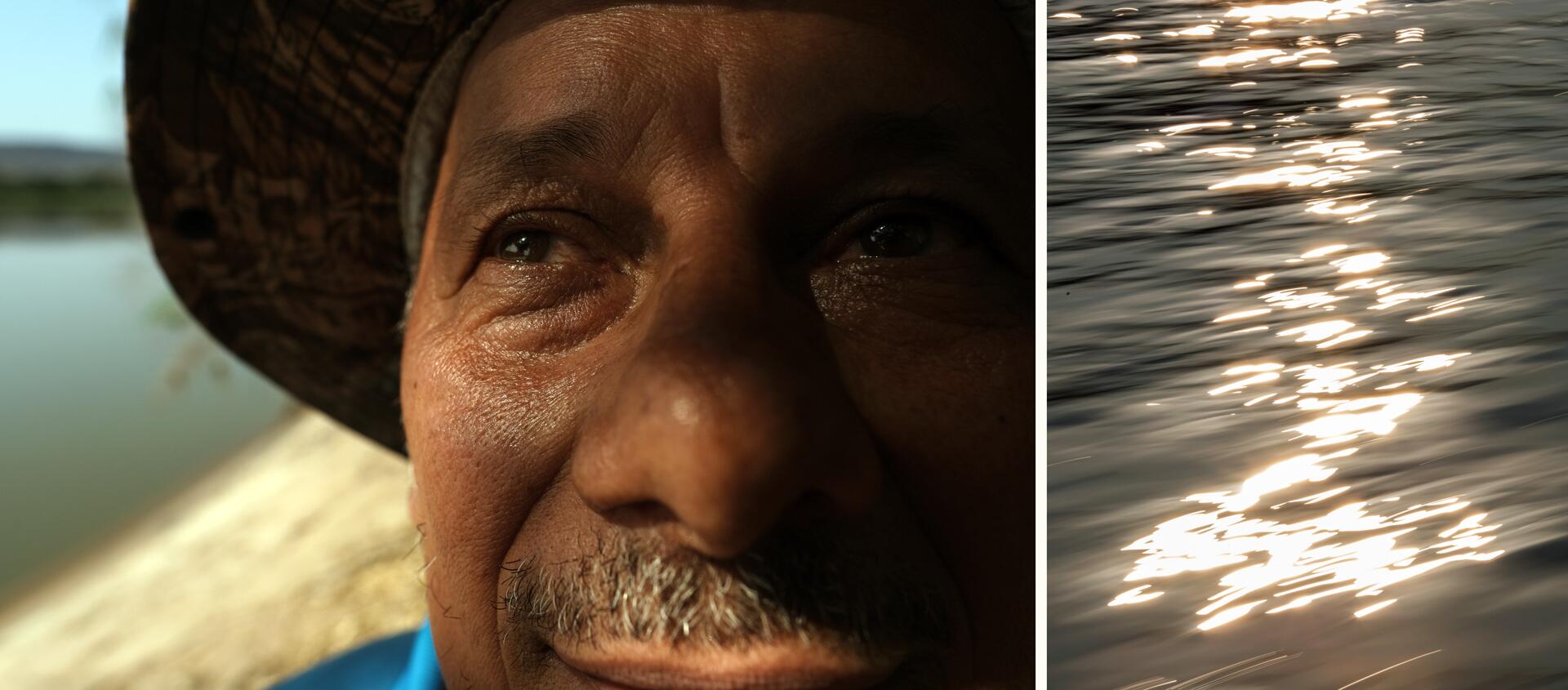

Another who heard the cries was a 53-year-old Ribeirinho called Lourenço Pereira Leite. A self-described “traditional fisherman, unschooled in writing, but fluent in River,” he was getting ready for another day of fishing when he looked from a distance at the bank leading down to the waters. Approaching, he noticed the color had changed. “The River had gray stripes. I saw they were actually ashes, from something burning. Besides that, thousands of dead fish. At the time I despaired, and cried with the River. It felt like it was dying at my feet. But then the people around me reassured me. They said the River is strong; it was hurt, but would recover. That was true. The Paraguay River is unassuming, but strong, see? That’s why I’m the third generation of my family to live on its banks.” The River did in fact survive, but it hasn’t been able to heal its wounds from the fire and so many other human attacks in its recent history. The cycle of inundation in the Paraguay River, the ebb and flow of the waters that results from the fundamental process of flood and drought and leads to the creation of the lives in the Pantanal biome, is no longer the same.

The Dourado Fish knows this well. Its complex and delicate dialogue with the River happens from inside the waters. A valiant predator, for years the currents had alerted the fish when the time came for spawning. The River announced it through changes in temperature and water level. When the Dourado received this signal, it would interrupt whatever it was doing, ready itself, and leave on a long journey. It swam upstream, against the currents, to spawn in the headwaters, newly flooded by the season’s rains. Until recently, this was an ideal place to spawn. Now it’s a confusing signal. The River no longer knows how to specify the right time to spawn. Its springs are drying up, and the womb that generated so many new lives is now becoming infertile.

The construction of small hydropower stations, which started more than 20 years ago, along with the advance of agribusiness – mainly soy plantations and cattle ranches – have brought deforestation, toxins, erosion, and sedimentation. The River’s springs are being destroyed and its natural flow altered. The climate crisis has reduced levels of rainfall that for millennia dictated the rhythm of flooding. An analysis by the website MapBiomas showed the area covered by water in the Pantanal shrank by almost a third (29%) between the flooding in 1988/1989 and 2018. The main causes were changes in climate, deforestation, and the encroachment of agribusiness – the same thing responsible for a reduction of more than 15% of the water cover in the Amazon region in recent decades.

Lourenço Pereira Leite wept when he saw thousands of dead fish. Solange Ikeda explains that the flood cycle of the River creates the Pantanal

Sometimes pleasant, sometimes tense, this conversation with the waters of the Paraguay River is a part of the everyday life of Isidoro Salomão, a 50-year-old Ribeirinho in the Pantanal who was born River before being born person and who now coordinates, along with Vanda, a key movement in the River’s defense – the Paraguay River Grassroots Committee. “I was gestated by the River. When my mother was pregnant with me, she spent more than a month floating on these waters after the truck carrying her and her family fell into the River and was carried off by the current. I was born on a bank of the River and never left its side. The River is a corridor of lives, it is many lives. It welcomes rainwater, and it welcomes our bodies too. That’s why we’ve been fighting for decades to keep it alive, sustain the magnitude of its flood cycles, its life cycles.”

These flood cycles are, incidentally, a principal characteristic of the Paraguay River and give it its personality, both unassuming and powerful at the same time. “To understand this River and its movement, you must understand it lies within a system formed of plateaus and plains. The headwaters are on the plateaus, on the highlands, and during periods of rain, their waters flow down to a large basin: the plains of the Paraguay River. These plains are very diverse. There the River is winding, full of curves, which is why the water flows so leisurely, producing the annual floods typical of the region. The floods create a unique water cycle, and as a consequence a unique biome, the Pantanal,” said Solange Ikeda, professor at the University of Mato Grosso.

Someone who deeply enjoys the flood cycles is the Ingá, a tree who found the winding corners of the River’s banks a welcoming place to set down its roots. In the rhythms dictated by the water, it submerges part of its body and soon watches the soil dry out. It’s almost a slow dance, with movements only a pair attuned to each other their whole life can master. And one that is now at risk of ending, threatened by the progress of a large waterway project that jeopardizes the curves of the River where the Ingás have lived for centuries.

Known as the Paraná-Paraguay Waterway, this megaproject also threatens the lives of Salomão, Vanda, Lourenço, the Dourado, and so many others with roots there. The idea is an old one. It was conceived in the 1980s and its main objective is to reduce costs and facilitate exports of raw materials like Brazilian soy to neighboring countries on large freighters. But for these vessels to travel downstream as fast as possible at the lowest financial cost (the cost to Nature is enormous), the curves of the River need to be straightened and its soil dug out; it must be dredged to speed the flow.

Isidoro Salomão was born River before being born person and now protects its waters

“This would end up killing the Paraguay River. First, because there are plans to transport pesticides, which could contaminate the waters even more. Second, because without its curves it might still be a waterway, but it wouldn’t be the River we know today. There would be no more flooding, no more Pantanal way of life,” said Salomão, who for decades, along with Vanda, has coordinated grassroots movements to protect the River.

In that region alone, they have helped form 13 grassroots committees, one for the Paraguay River and the other 12 for each one of its tributaries. The community’s fight has been taken up by activists, fishers, and university professors from Brazil and other countries in South America. “We have various initiatives with other countries so each region can protect the River in its own way. In the end, it’s Nature; it doesn’t have borders,” Salomão said.

A few times a year, since the 1990s, Salomão and Vanda have organized meetings of what they call the Activism School, founded to spread the tenets of a systemic vision of Nature, one that considers the whole and not just fragments and is in harmony with the environment. The meetings are usually held in their homes, but recently, during the pandemic, they moved online. On these occasions, the River has had its own camera, so it could participate in the meeting like a member – indeed, as the group’s main member. Sharing the computer screen with the faces of other participants, its movements, sounds, and colors dictated the rhythm of the meetings and warned that a solution was urgently needed. “Everyone would be quiet for a time, just watching the movement of the water. After all, everyone needs to learn to listen to the River. And it tells us where it hurts,” Vanda said.

In order to make way for freighters, the curves of the Paraguay River would need to vanish

The community’s fighting spirit, propelled by the strength of the River, has borne fruit. For example, on November 14, 2000, a protest against the megaproject paralyzed the city of Cáceres. On that occasion, the then governor of Mato Grosso state, Dante de Olivera (PSDB), was in town to take part in a public hearing on the environmental licensing of the Port of Morrinhos, which would have become the birthplace of the Paraná-Paraguay Waterway. The public backlash was so great that shortly after this large protest, the environmental license was suspended. The win was so momentous that the day was officially recognized as Paraguay River Day. “We won a right for the River. It deserves it. It became the first River in Brazil to have a dedicated day. Every year we have a large celebration. The River calls us and we come, it welcomes us and that comforts us,” Vanda said.

But in the same city that so welcomes and is welcomed by the River, there are people who insist on turning their backs to it. They absolutely refuse to become currents. And that is why they won’t give up on the idea of killing life off bit by bit. According to researchers, the state doesn’t currently have an official waterway project, but since 2018, individual licenses have been approved for ports in different parts of the Pantanal, reigniting fears about the megaproject. Some researchers believe getting smaller projects approved was a way to go about building the waterway bit by bit. In January 2022, for example, the Mato Grosso state environmental council granted a preliminary license to build the Port of Barranco Vermelho, in Cáceres. The principal objective was the transportation of grains (soy) to the south via the Paraguay River, which would need to be modified in some sections, including untouched, protected areas of the biome, to allow the movement of large vessels.

Vanda, Salomão, and the group of activists were aware of these developments and had been preparing for this new chapter of the fight for some time. In the back and forth of their meetings, travels, and collaborations to protect the waters, they came across an idea that had been floating around the world for decades: the understanding that Mother Earth is a living entity and all her beings, human or more-than-human, are intrinsically interconnected and therefore must be given the same level of protection. This understanding has propelled groups around the world to fight for the inclusion of fundamental legislation at different levels of government to protect Nature, putting up obstacles against projects that can cause it harm.

“Our relationship with the group of lawyers working from the perspective of the rights of Nature developed organically, through meetings and conversations with the different organizations. It was then we understood we had a very interesting legal tool to help us in this fight,” said Mariana Lacerda, a lawyer with the firm PesquisAção, who acted as legal advisor to the grassroots committees who filed the lawsuit leading Cáceres to become the sixth city in the country to recognize the rights of Nature as law.

On July 17, 2023, after groups who defend the River spent months dialoguing with other sectors, the city council unanimously approved a bill, authored by councilor Cézare Pastorello (PT) and signed by 10 of the city’s 15 councilmembers, amending the city’s charter. The session, considered “historic,” featured rounds of applause and packed galleys – very rare for the region.

The city’s charter is considered a municipal constitution, and on that day, some of its articles were amended so all elements of Nature, and not just humans, were made rights holders. In a section of Article 1 of the law, for example, it was made explicit that the city aims to “develop itself, based on its political-administrative autonomy, […] in harmony with nature.” Article 204 contained a section stating it is the responsibility of public authorities to “defend the Right to integrity, understood as the right of all elements of nature to maintain their ecological functions and develop freely, without harmful human interference.”

In this way, Mariana explained, Cáceres joined the ranks of Brazilian cities that had raised the standard of protection not just for the River, but for an entire biome. In this case, the Pantanal. “All other laws, projects, and public policies would have to adapt to this new level of protection, which would create a barrier to the approval of new bills and potentially damaging municipal works. For example, it is often necessary for the municipality to certify that major construction projects, such as ports and hydroelectric dams, are in compliance with zoning regulations that define legal forms of land use. Under a city charter granting rights to Nature, these structures would probably not be approved because of the potential damage to the environment. It would be a new way of thinking and relating to nature,” she said.

Heading towards a change in mindset

“They think that, like humans, I glide alone and silent through the bowels of the Earth. But I am much more than a mere current. In the flow of my waters, you’ll find not only my history but the heartbeat of thousands of lives”

In Cáceres, the change in the city’s charter has inconvenienced powerful people. The same people who resist becoming currents. Please understand: for those who are not born to the River like Solomon and Vanda, letting yourself be guided by the rhythm of the waters may sound poetic, but it implies a deep and sometimes painful dive into consciousness. A full-body dive, including the soul. You have to die as one (the human) in order to be reborn as countless (Nature). It involves shifting your gaze to understand the center of the world is not in your own navel, but diluted among all the navels in the world. To understand human life is just one in a tangle of interdependent lives, and they all have the same right to exist. For some time now, the planet and the peoples-nature have been warning us about this, and the climate crisis we are experiencing today is the most explicit manifestation of the fact that the anthropocentric and individualistic perspective dominating Western thinking is incompatible with all life.

The idea of bringing this perspective to the domain of law – a vision which breaks with the very origins of this system of rules devised to bring order to societies – has faced resistance but has also mobilized thousands of people across the world. These are professionals and academics who, for some years now, have been dedicated to bringing to the legal sphere the idea that the unprecedented crisis we are experiencing today could be an opportunity to rethink the relationship between human beings and their surroundings — and legislation is a fundamental path for this process (Read more at the bottom of the page).

A journey to renaturalize the world

Different ways of legally enforcing the rights of Nature are being tested around the world. It all started in 2006 in the United States, in the town of Tamaqua, Pennsylvania. Toxic waste dumping mobilized the directly affected local community, who heard Nature’s cry for help. After much public pressure, what has come to be considered the world’s first rights-of-Nature bill was passed. It banned pollution and specifically named “natural communities and ecosystems” as beneficiaries of the rights guaranteed by law, alongside humans. Several other cities subsequently began to implement legislation with the same principles, some focused on a specific entity – here Rivers take center stage – and others more general, encompassing the rights of all more-than-human beings in a region, as was the case in Cáceres.

In 2008, Ecuador became the first country to recognize the rights of Nature in its constitution. Two years later, in 2010, Bolivia passed a federal law that began to shape society from an ecocentric perspective, based on the premise that human life needs to be in harmony and balance with its surroundings. “Today, more than 40 countries have implemented laws or have court cases debating the issue. They are changing the way we look at and think about Nature,” said lawyer Vanessa Hasson, general director of Mapas, an international organization promoting rights of Nature since 2004 and an expert member of the United Nations Harmony with Nature program.

In Brazil, the first municipality to adopt this approach was Bonito, Pernambuco, in 2017. Four others followed suit: Paudalho, Pernambuco; Florianópolis, Santa Catarina; Serro, Minas Gerais; Guajará-Mirim, Rondônia; and, most recently, in November 2023, Alagoa Nova, Paraíba. As a result, projects with the potential to degrade biomes have been halted in these locations, and other projects to protect Nature have been implemented. One example was the suspension of a licensing process for iron mining in Serro, Minas Gerais in January 2024. By court decision, after mobilization of the community, which argued for rights of Nature in the region, the project was halted due to the potential for degradation of flora and fauna and the impact on native peoples. In Guajará-Mirim, Rondônia, the approval of the Rights of Nature Law led to the approval of another law, which granted rights to the Laje River (Komi Memem) and led to the establishment of a committee of River guardians with the aim of conserving and maintaining its rights. Recently, the local community began mobilizing to demand a halt to the use of pesticides in the region because of their potential to degrade the waterways.

“But we need to understand the goal is much bigger. When we think of legislation, we immediately think of litigation, of prohibition. We forget the law has three main functions. The first is to guide society, the second is to provide practical regulations, and the third is to sanction. In our understanding of rights-of-Nature laws, the main impact is its educational function, the idea of proposing a new way of looking at ourselves and Mother Earth, and making society internalize it,” Vanessa Hasson said.

As far as Ecuador is concerned, the formula seems to be working. Natalia Greene, vice-president of the Ecuadorian Coordinator of Organizations for the Defense of Nature and the Environment, says that 15 years after the Constitution was changed, the perception of the issue in the country is already very different from what it was at the beginning of the century. “I believe you can change people’s imaginations through the law. That’s what we’re looking for. It’s not simply about a change in the law, but about having laws that change the system [of thought as well]. In Ecuador, for example, we no longer question whether Nature has rights or not. That’s a given. What is questioned is why these rights are not guaranteed. And this has incredible reach, which could escalate globally,” she said. In fact, what once seemed an unlikely achievement for a group of Kukama Indigenous women from the Parinari district, in the Loreto province and region of Peru, has recently become a reality. In March 2024, after long years of struggle, the women’s group managed to pass a law recognizing the Marañón River, a waterway flowing through the region that has long suffered from constant oil spills from the Norperuano Pipeline, as a legal person.

A current resisting the might of the countercurrent

“For a long time I witnessed in horror the scars human hands drew along my banks, straightening my curves, eliminating my idiosyncrasies. Not anymore. I raise my voice above the sound of water. It’s time to take back the leading role in my story – which is also our story”

In Cáceres, the Rural Union, to which a large part of the region’s landowners belong, was not at all enthusiastic about this idea of a paradigm shift. That’s why, as soon as its members heard the bill had been approved, they drew up a document suggesting the proposal might be unconstitutional. The document called for the “immediate repeal” of the amendment to the city’s charter. “Concurrent legislative jurisdiction on environmental matters notwithstanding, the Union is responsible for legislating on general norms, while the legislative jurisdiction of states and municipalities is restricted to supplementing the general norms issued by the Government,” stated the document sent in mid-July to the president of the chamber, Luiz Landim (Green Party). This argument does not make much sense, according to legal experts. Article 225 of the Constitution states everyone “has the right to an ecologically balanced environment, […] imposing on public authorities and the community the duty to defend and preserve it for present and future generations.” In Brazil, states and municipalities can be stricter than federal laws, not more lenient. “In other words, the protection of Nature can, and should, be greater than what is provided for in the Constitution. There was no unconstitutionality; in fact something similar has already been done in five Brazilian cities and there was no challenge. The Federal Supreme Court has already issued several decisions removing any doubt in this regard – states and municipalities can legislate in ways that compete with the federal government, as long as it is in ways that are more protective of the environment,” Vanessa Hasson explained.

Despite this, the proposal was endorsed by council member Flávio Negação (Brazil Union) and four other council members; they submitted a new amendment to the city’s charter to repeal the recently modified sections. Less than a month after the historic city council session advancing environmental protection put Cáceres in the pages of newspapers all over Brazil, the rights of Nature were repealed by 11 votes to 2 in the first round and 10 to 2 in the second – only council members Cézare Pastorello and Mazéh Silva, both in the Workers Party, voted against revoking the law. At least six votes in favor of the repeal were cast by the same council members who had signed in support of the bill a short time earlier. Flávio Negação declined to be interviewed. “We’re disgusted, but all this also gives us more strength to continue our fight. The fight for our life, which is also the life of the whole Pantanal,” Salomão said.

Before leaving Cáceres, I said goodbye to the River, in the company of Vanda and Ahmad, the photographer who was traveling with me. From the boat, I saw a Dourado jump out of the water. It seemed to know where it was going. Two Tuiuiús strolled along the banks of the river, grunting loudly in a sonic duel with screaming Vultures. We stopped and Vanda started singing along. She sang an ode to the River, weaving together history, tradition, love and the ancestry of Pantanal life. All this while the setting sun was being swallowed up by the horizon. I thought about how the Paraguay River is unassuming and powerful – and also intelligent. It is capable of entering the entrails of fish, the dreams of humans, and even changing a foundational element of social structure: the law. The River doesn’t stop being life, welcoming life. Now I no longer had to close my eyes to hear its voice. It echoed from all sides, in a blending of sounds that boiled down to a simple and powerful desire. The Paraguay River simply wants the right to be Nature.

“My waters not only reflect the light of the sun, they are also a mirror of your existence, your choices and actions. You need only pause in my riverbed to hear the stories my current carries and the futures you long for. You need only listen to me for us to flow towards a possible future”

‘WE ARE MANY’

What is the difference between environmental rights and rights of Nature?

During the course of other social movements that gained ground during the 1980s, the need was felt to bring the debate over the rights of Nature into the legal realm. In the face of a collapsing climate and gravely endangered biodiversity, people began to question longstanding concepts that linked development and domination and were built on the principle that evolution only takes place when the human is separated from Nature.

This proposal challenges the foundations of Western society, and is premised on the Cartesian view situating us as external observers of the environment we live in. It is provocative because it confronts the idea of humans (especially men) as the center and Nature as a “resource,” a view that has thrived because it has long been convenient – and very profitable – for the minority dominating the global political-economic system. Ultimately, it gave us a false sense of control over Mother Earth.

Unlike the premises of environmental law, which is based on the idea that Nature is an appropriable resource – and one that can be protected by humans to guarantee their own well-being – the rights of Nature current of belief proposes an ethical-legal paradigm defending the thesis that Nature has an intrinsic value and is not an object of humans’ rights.

Thus, the rights of Nature current seeks to connect with ancestral and Indigenous knowledge, which recognizes the interdependence of all natural elements – be they animals (including humans), plants, or minerals. And in this current, these elements are not objects, but subjects of rights. How does this work in practice? Attorney Vanessa Hasson, general director of Mapas, an international organization that since 2004 has been promoting Rights of Nature laws and public policies needed to make them a reality, explains: “In many ways. Nature is many, we are many, and so too should be the ways of protecting it.”

More-than-Humans is a partnership project between SUMAÚMA and More Than Human Rights (MOTH), an initiative of the Earth Rights Advocacy Clinic at New York University (NYU) School of Law.

Report and text: Jaqueline Sordi

Photos: Ahmad Jarrah

Concept and editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Maria Jacqueline Evans and Diane Whitty

Layout and finishing: Natália Chagas and Viviane Zandonadi

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

More-than-humans project coordinators: Talita Bedinelli (SUMAÚMA) and Carlos Andrés Baquero-Díaz (NYU)

Editorial Director: Eliane Brum (SUMAÚMA) and César Rodríguez-Garavito (NYU)