From time immemorial, my people —the Xipai—have had an intimate relationship with the Iriri River. It’s part of our family. The River has always been the River; the Xipai have always been the Xipai. Two different bodies entwined as one.

But the Iriri of my ancestors’ time, a River of waters that run crystal clear below but appear dark brown on top, is changing. In summer, our dry season, the River inexplicably turns bright green. Intrigued, I decided to find out why.

To tell this story, I needed to sharpen my ears and eyes. I needed to listen to the River.

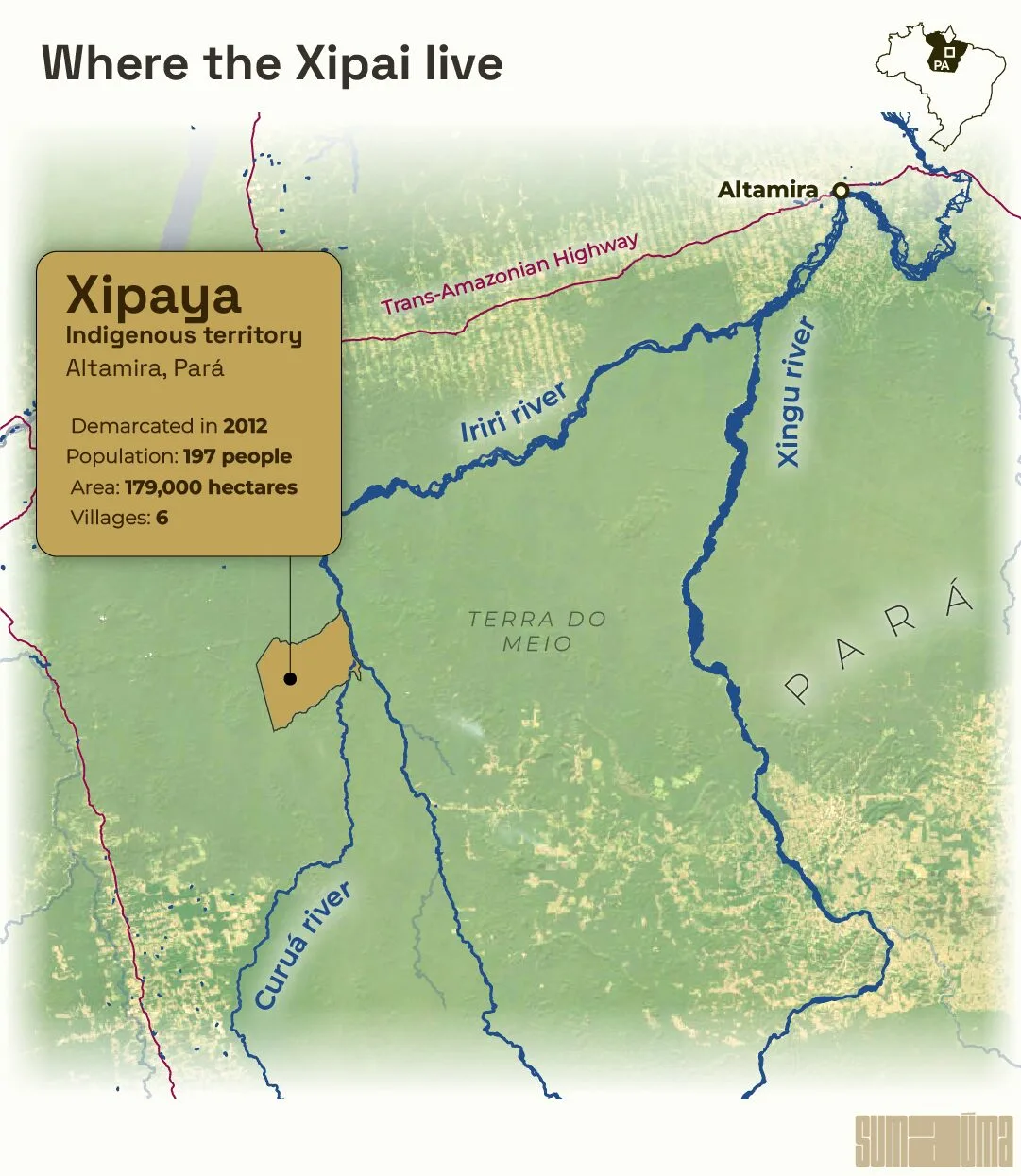

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

The Iriri is the largest River in the municipality of Altamira, in southwestern Pará state. It is born in the Serra do Cachimbo highlands, in southern Pará, from there meandering through the Amazon until meeting up with the Xingu River. At some spots along its 900-kilometer extension, the River is as much as two kilometers wide. In the area known as Entre Rios—between the rivers—the Iriri is joined by the Curuá, whose waters now run muddy as the result of illegal mining operations that take place outside our lands, which make up the Xipaya Indigenous Territory. Demarcated in 2012, our area is home to 197 people scattered across six villages, three on the Iriri and three on the Curuá.

The bed of the Iriri is lined with rocks of myriad shapes and sizes, which emerge from the water during the dry summer. The riverbed looks like an art gallery that exhibits stones instead of famous masterpieces—the art of Nature herself.

This house-River is home to forest-peoples, fungus-peoples, plant-peoples, bacterium-peoples, and phytoplankton-peoples. I had to silence myself to hear them all at the same time—sounding like a huge, powerful orchestra. You can’t talk about the Iriri River without talking about the Iriris, forest-peoples, and more-than-humans who live in harmony with it. They aren’t just part of the Iriri—they are the Iriri.

To tell the story of this river, I went to listen to what all of these peoples had to say. I dove into the Iriri in an attempt to drown, and my body sank to its bottom like a rock.

I’m using the words “drown” and “sink” in a figurative sense, to express my desire to understand the River as deeply as if the very Iriri were speaking to me. I waded in up to my knees and returned to the rocks. I mistook a baby Surubim fish for an Anaconda because of its colors and the reflection in the water. I realized everything that belongs to the River has its own different shapes, bodies, and customs, and yet they all live in tune with each other, as part of a single body, the Iriri.

I’m still lying at the bottom of the River, still in its depths, as I write this story. I failed to become River even though I am Xipai, and I feel like an intruder in this beautiful, frightening place.

Rock bottom: when the water recedes during the dry summer months, natural sculptures emerge from the Iriri riverbed

Greener water, drier land

Biupa Xipai, 57, is the deputy cacique (head) of Tukamã Village, where he has lived since 1994. Tukamã is located about 600 meters from the edge of the River. Its wooden houses stand in a circle and the ground is covered with grass. Most roofs are made of Brasilit tiles, a composite of cement and synthetic fiber; a few small buildings that serve as outdoor kitchens are thatched with Babassu palm. This is where the villagers make handicrafts. In the central courtyard and backyards, trees bear mangoes, bananas, tangerines, rose apples and other fruit.

For the Xipai, daily life revolves around the River. Families fish in the feeding grounds near the village port or farther away. Sometimes they spend all afternoon by the River, mothers washing clothes or bathing and children, most of whom already know how to swim, playing in the water. The young ones often engage in a game where one child pretends to be a Cayman or Anaconda, and the others flee. The men go out fishing, while the women wait for them to return and then prepare the catch for the family meal. In the evening, families gather in a circle and tell stories of what they have seen or experienced in the River or rainforest. Young people and children listen to tales filled with Jaguars, Anacondas, and other animals that live around the Iriri.

Village children live in the Iriri: for the Xipai, life revolves around this body of water

Biupa Xipai is well aware of what has happened to the Iriri River in recent years.

“Starting in June, the water goes green. [From then on,] we no longer see the original water,” he told me as we chatted at his home, me on a chair and him lying in a red hammock. Biupa rolled a cigarette and then let it dangle from his fingers, his arm swinging from the hammock. It made me nervous because every now and then, when he got carried away with a story and shook his arm, I got worried the cigarette might end up on the ground.

In the Amazon, seasons are named according to rainfall, not according to the four-season calendar of temperate climates. The so-called Amazon winter is our rainy season, lasting from November to April, while summer runs from May to October. Biupa Xipai says when you look at the surface of the Iriri in the winter, its waters are darker, a murky shade of brown. But if you dive in, you’ll find the water below is almost crystalline, and you can see fish swimming among the rocks and in the fine sand gently swirling up from the riverbed. In the winter, the water is still the same color it used to be, but it is changing in the summer. It begins turning swamp green in June and stays that way the whole month.

When the River is consumed by green, things get tougher. It becomes a challenge to see what’s underwater or even on the surface, even for the trained eyes of the Xipai, who sometimes leave their villages to fish at night because of the heat. With poor visibility in the water, it’s harder to see the fish and avoid bumping into the rocks.

In July, August, and September, at the height of summer, the temperature climbs and the water grows opaquer and an even deeper green.

That’s when the fish start to die.

Biupa Xipai is worried about how the Iriri River has changed: “We don’t see the water like it was before”

Biupa has observed that scaleless species, like Surubim, Skates, and river Catfish known as Cuiú-cuiú, are the first to die. Three days before his interview with SUMAÚMA, Biupa spotted a dead Cuiú-cuiú floating on the water. He checked for signs of a predator but there wasn’t a scratch on the fish’s body. It was probably the first victim of the greening of the River that Biupa had seen this year.

Biupa doesn’t know exactly what is turning the Iriri green, but he does know the phenomenon has been getting worse in recent years. “It’s changed a lot in the last five years. The water is really different. There’s climate change too. It’s July now, but [because of the heat] it feels like August,” says Biupa.

In October, the waters of the Iriri remain green. They should return to their natural brown when winter arrives in November.

But, due to climate change, winter no longer arrives in November.

Last year the rains didn’t come until December. That’s when the River turned dark again.

Kamadï Xipai, 45, and Kawhe de Jesus Paz, 50, have been married for over 27 years. They both live in Tukamã Village. Kamadï is a school cook and artisan and Kawhe is an Indigenous sanitation agent and also an artisan. They spoke with SUMAÚMA under a Mango Tree in their yard.

According to the couple, the Iriri River didn’t rise as high as usual in 2024. Tukamã Village lies 600 meters from the riverbank, and during the rainy season the waters should invade the adjacent floodplain forest, inundating over half the ground between the riverside and the edge of the village.

Kawhe de Jesus Paz and Kamadï Xipai, from Tukamã Village: in 2024, the waters of the Iriri failed to rise high enough to meet the needs of people, fish, and tributaries

None of this land was underwater this year. It rained less, and the Iriri didn’t have enough water for the Xipai, the fish, the floodplains, or any of the ecosystems that needs these high waters.

Nor did the River invade the floodplain alongside Yupá, a small village home to 13 people. There the trees crowd up to the houses, which are surrounded by wooden boards and covered with concrete tiles or Babassu palm. The village is located 300 meters from the riverbank, and this whole area should be underwater in winter. But this year the water barely flooded even four of those 300 meters.

The drought is so bad this year that on September 30, Brazil’s National Water and Sanitation Agency declared a critical situation of water scarcity on both the Xingu and the Iriri, one of its affluents. The aim is to alert the public and allow local institutions and companies to take action.

In Yupá Village, stones where there used to be water: the situation of the Iriri and Xingu rivers is considered critical

But why exactly is the water green?

I spoke to two biologists who might help us understand what is happening to the Iriri. Dilailson Araújo de Sousa, a technician at the Ecology Laboratory at the Altamira campus of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), holds a master’s degree in continental water resources in the Amazon and is a doctoral candidate in ecology at the UFPA. Daniela Santana Nunes, a professor with the school of biological sciences at the UFPA Altamira campus, holds a master’s in the ecology of estuary ecosystems and a PhD in socio-environmental development.

Both of them analyzed photos taken at different points along the River. They also listened to my report of everything I had seen, experienced, and heard about dying fish, water color, and rising temperatures in the region. They both came to the same conclusion: much like what has happened to the other rivers and lakes these two biologists have studied in recent years, the greening of the Iriri can apparently be blamed on the uncontrolled proliferation of cyanobacteria, commonly known as blue-green algae, microscopic beings that make up phytoplankton and float on the surface of river waters.

Close-ups of the Iriri: bathing in the River, a routine part of Xipai life; a corner of greenish water

In the assessment of both scientists, few microorganisms other than cyanobacteria are capable of taking over fresh waters, as is happening to the Iriri River. Everything in the region signals a process of environmental imbalance exacerbated by climate change. “The proliferation of cyanobacteria indicates an imbalance in ecological interactions within a given system. When there is an overgrowth of a group of organisms in this environment, it means something is wrong; this group is at an advantage,” Dilailson said in an online interview. The UFPA biologist, now 40, has been studying phytoplankton for 16 years and focusing on the action of cyanobacteria for the past 11.

A few factors favor this propagation, the first of which is an increase of organic matter in the water, especially of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous—what biologists call eutrophication. In the Amazon, this is directly associated with illegal mining, an activity that involves digging up land and stirring up water. Rich in nutrients like phosphorous, nitrogen, and calcium, the sediments produced by mining activities are thrown into Rivers, where they become food for cyanobacteria.

In Tukamã Village, artisan Kamadï can still remember the first time the Iriri River turned green, back in 2003. “It was the first time we had that [green] water, and a lot of fish died,” she says. Massive numbers of fish in fact. After local fishers and residents reported the problem to Brazil’s environmental protection agency Ibama, the latter sent a team to test the water and fish, with the support of the federal Indigenous agency Funai and Eletronorte, as well as researchers from the Biophysics Institute of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Paulista State University, and the Evandro Chagas Institute. Laboratory reports confirmed the cause to be a blue-green algae bloom of potentially toxic genera. The scientists compiled a research report that recommended the implementation of an ongoing monitoring plan for the Iriri and Curuá rivers, since these algae blooms may reoccur in subsequent years. The Iriri monitoring plan never left the drawing board.

The document produced by the scientists mentioned plans to build a hydroelectric power plant in the region: Belo Monte. The report included among the project’s environmental risks blue-green algae blooms, which are generally more serious in the standing waters of reservoirs. In operation since 2015, the Belo Monte hydroplant dammed up the Xingu River.

I asked Norte Energia, the consortium that owns the concession for Belo Monte, if the company was aware of what was happening with the Iriri or if they monitor the River’s waters. Norte Energia replied that it does not monitor the waters of the Iriri because this River does not lie within the plant’s area of influence.

In 2017, Brazil’s Indigenous agency received reports that members of both the Panará Indigenous people, who live at the headwaters of the Iriri, and the Kayapó, who live farther down the River, had fallen ill after drinking water from the River. There were likewise reports of fish dying. Tests coordinated by the Special Office of Indigenous Health and conducted by the federal environmental agency and Mato Grosso State University confirmed the presence of bacteria and toxins in the water.

One problem with algae blooms is that they release toxins into the water, which can be deadly for animals and even humans. These include hepatotoxins, which affect liver function and may also affect the kidneys; neurotoxins, which affect the brain; and dermatoxins, which irritate the skin. In 1996, more than 60 people died at a dialysis clinic in Caruaru, in Pernambuco state. Investigations of the water used in dialysis detected the presence of, another toxin produced by cyanobacteria.

This year brought further reports of people falling ill after drinking water from the Iriri. Villagers in Yupá have experienced episodes of nausea, vomiting, malaise, and diarrhea.

The health of Nature and those who live in it: after drinking water from the Iriri, Indigenous people reported nausea, vomiting, malaise, and diarrhea

The River belongs to no one

In September 2024, I contacted the regional coordinator of the federal Indigenous agency Funai in Altamira, Luis Gonzaga Xipaia de Carvalho. In a WhatsApp message, I asked whether the agency knew the Iriri was turning green and the fish dying and whether they had considered testing the River’s waters or devising an emergency plan for the Indigenous groups living in the region, should the situation with the Iriri worsen. The coordinator said the agency was not aware of the Iriri turning green.

I also sought information from a technical unit of the environmental agency Ibama in Altamira. By email, I asked whether Ibama knew about the state of the Iriri River and whether they had drawn up any plans for testing and monitoring the water. The agency said it had no knowledge of what has been happening to the Iriri around this time of year. The agency also said federal rivers are tested by the National Water and Sanitation Agency, in partnership with Brazil’s Geological Service. Furthermore, they said the Iriri is classified as a state River and therefore the state’s department of the environment is responsible for monitoring its water quality.

When contacted, the Pará state department of the environment said Indigenous territories are a federal responsibility, but it said nothing about monitoring Iriri River water. I pointed out that we were asking not only about the 30 kilometers of the Iriri inside Xipai territory but about the entire River, whose 900 kilometers lie almost wholly inside the state of Pará. We received no reply.

Why are the fish dying?

Cyanobacteria are among the oldest living beings on the planet, having first appeared some 3.5 billion years ago. Over the course of their long life on Earth, they have developed great buoyancy, which increases with water temperature and density. This brings them to the surface, where they receive more sunlight and reproduce even faster.

Meanwhile, the mud formed by accumulated sediments—such as those produced by mining operations—feeds the cyanobacteria while likewise preventing sunlight from penetrating deeper into the water.

This is when the fish start to die.

Professor Daniela Nunes explains that during a blue-green algae bloom, fish deaths are associated with two factors: first, the cyanobacteria consume and deplete the nutrients in the water; second, the bloom on the water surface keeps the sunlight from reaching deeper parts of the River. Other freshwater phytoplankton are therefore unable to perform photosynthesis on the river bottom. With less photosynthesis occurring, there is less oxygen in the water.

“There is a process of oxygen loss in the lower layers of the water, and this can lead to fish deaths,” says Daniela, who has been studying the diversity of algae in Amazonian rivers for 24 of her 47 years. Last year, she was working to compile a list of cyanobacteria found in Pará.

The Iriri seen from Yupá Village: federal agencies say it is a state River, but the Pará state government says it is federal since it cuts across Indigenous Territories

Biologist Jansen Alfredo Sampaio Zuanon, 60, a researcher at the National Institute for Research on the Amazon, is exploring why scaleless fish, such as Catfish, are the first to die. When the nutrients that nourish cyanobacteria are used up, the bloom ends. The biomass from the bloom sinks to the river bottom, where it encounters organic matter, dead animal remains, aquatic plants, foliage, and whatever is brought in by the rainfall—this is the River’s natural cycle. All this accumulated organic matter then starts decomposing, and the bacteria involved in the process consume more oxygen at the bottom of the River. This first affects the scaleless fish that live there, such as Catfish.

When the oxygen at the bottom is used up, Catfish or other species swim to the surface to breathe, but they consume a lot of energy doing so. Instead of feeding, they focus on getting oxygen. “They expend more energy and, unable to replenish their strength, they eventually die of exhaustion,” says Jansen Zuanon, who holds a doctorate in ecology and is one of Brazil’s leading experts on freshwater fish.

A time of uncertainty for the River and the Xipai

When a brown-watered River becomes green, life becomes uncertain for the people who are part of it. The Xipai no longer know whether they will be able to preserve their way of life and their intimate relationship with the Iriri. I had a feeling of dread (I’ll stop short of using the word “fear”) when I plunged my body into the River and when tears ran down Biupa Xipai’s face as he talked about the Iriri then and now.

For the rivers of the Amazon Basin, this is a time of terrifying drought and of rains that don’t arrive on time and aren’t enough to fill the rivers or allow people to put in crops. The temperature climbs higher every year, and studies show that climate change is making conditions perfect for blue-green algae to thrive. The Iriri River is in danger of growing ever greener, further threatening the existence of those whose lives depend on its waters.

The Iriri is the River where waterfalls and winds tell the stories of those who have long lived on or near it. It is the River where fish tickle swimmers’ bodies and the sound of thousands of lives echoes through the rainforest, roiling the water into whirlpools.

Iriri is the River of my village, my childhood, of my dreams and my ancestors. It is the River I belong to, where I remain submerged.

But for the Xipai of the future, this River of brown waters might become but a memory.

Xipai families bathing in the Iriri: climate change is threatening their intimate relationship with the River

The product of a partnership between SUMAÚMA and InfoAmazonia, this story received the support of Voices for Just Climate Action (VCA), which works to amplify local climate action and seeks to play a central role in the global climate debate. InfoAmazonia is part of the coalition “Strengthening the data ecosystem and civic innovation in the Brazilian Amazon,” along with the Black House Association of Afro-Engagement, Puraqué Collective, PyLadies Manaus, PyData Manaus, and Open Knowledge Brasil.

The product of a partnership between SUMAÚMA and InfoAmazonia, this story received the support of Voices for Just Climate Action (VCA), which works to amplify local climate action and seeks to play a central role in the global climate debate. InfoAmazonia is part of the coalition “Strengthening the data ecosystem and civic innovation in the Brazilian Amazon,” along with the Black House Association of Afro-Engagement, Puraqué Collective, PyLadies Manaus, PyData Manaus, and Open Knowledge Brasil.

Report, text and photos: Wajã Xipai

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Gustavo Queiroz and Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Art editor: Cacao Sousa

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum