“Not everything is seen by shining a light.”

Aldevan Baniwa (1974-2020), to whom we dedicate this story

1. failure

This is a story about failure. From start to finish. In my defense, all I can say is that it is an honest failure.

With the help of the scientists Noemia Kazue Ishikawa and Francisco Marques Bezerra, co-authors of this report, I have tried to crawl into the skin (skin?) of a fungus. More specifically, I endeavored to figure out how Coprinellus, a cosmopolitan genus, perceived our presence in a small patch of Amazon rainforest that still resists some six miles from the Brazilian city of Altamira, an epicenter of forest destruction. When we entered the forest in the darkness of a new moon, we witnessed an explosion of sexual activity among Coprinellus and all the other fungi as well. This was clear when we saw mushrooms spread out everywhere, in a broad gamut of shapes and colors, of luxurious textures and pungent smells. Mushrooms are the genitalia of fungi, and there they all were, on display and offering themselves up. When we sneaked into the rainforest, it was the time of mating games, selection, evolution, collaboration, and relationships. Intense life.

This isn’t at all to say our human bodies or pheromones had any effect on the fungi’s libido. There’s no way we, two-armed, two-legged creatures, would be of interest to them, other than for opportunistic or collaborative occupation—“opportunistic” and “collaborative,” of course, being terms drawn from human morality, since when fungi occupy us, it’s just life happening. This libidinous state of affairs (once again, explicit humanness) had been preparing itself for months before our nocturnal journey. The Coprinellus, whose sex organs were already mature, simply used us by impregnating our clothes and skin so we would transport their spores—as if we were their “mules,” carrying them to other parts of the planet with no risk of being captured at the border. We became another factor determining their success in fungifying the world.

In the case of the mycelia who happened to find themselves in a peaceful asexual phase but ended up disturbed by our lights or the flashes from our cameras, we played a somewhat more active role. Mycelia are entangled webs of fungi of the most varied genera and species, webs that these organisms use to communicate and interact with the roots of trees and other plants, as well as with insects, birds, and even mammals. According to scientists, if we were to lay all the mycelia found in one teaspoon of healthy soil end to end, the resultant string might extend anywhere from 300 feet to six miles. A living weave interconnecting much of life, these mycelial webs entwine with plant roots and shoots, with the bodies of animals, with sediments on the ocean floor, with pasturelands and forests. They create landscapes. In the words of Merlin Sheldrake, a mycologist—as fungus researchers are known—what we call hyphae are cells, “fine tubular structures that branch, fuse, and tangle into the anarchic filigree of mycelium,” a “growing investigation,” “speculation in bodily form.” These hyphae are the threads of the intricate embroidery that is mycelium, and mycelium is “not a thing but a process.” The rainforest and much of the planet are sustained by this colossal mycelial network, an absurdly skilled, living entanglement. We don’t see it and don’t talk about it much, but were it not for this vast network, the Amazon rainforest would be very different.

Taken on a night walk through the forest in Altamira, this image captures the moment a fungus of the genus Fuscoporia produced spores that seemed to fly. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Let’s pause for a paragraph to think about this. About the beauty of this. A planet sustained by a living web, much of it underground, engaged in intense activity and constant conversation with myriad beings. This is astoundingly beautiful. And we ignore it. But that’s how it is wherever enclaves of nature still endure. And things must continue like this if our species wants to continue existing.

In the forest, our intrusive lights may have triggered the emergent production of mushrooms, anticipating sexual exchanges by some weeks or even months and generating something akin to a baby boom. As we trod over the plant litter and branches on the ground in our hiking boots, we wounded the mycelia, either because of our weight or because we broke through the substratum. Yet even an injury can stimulate the reproduction of fungi, these great survivors. They may have been confused by the sudden illumination, interpreting it as the creation of a clearing by a fallen tree, which would imply plenty of food for their future generations. Fungi are remarkable living beings—and that’s why they have been on the planet for at least a billion years. They helped create the Amazon and all other forests.

What I’m trying to explain, from the fungi’s point of view, is how they might have understood this “visit” by humans, beings who move around on two legs, with two arms attached to their trunks, while their brains rest (and in some cases never wake up) inside a ball held aloft by a stem called a neck. From everything I’ve studied about fungi, if they were interested in giving their opinion, it would hardly be flattering. Merlin Sheldrake, a Brit who became a best-selling author thanks to fungi, described them to one of his mesmerized audiences in these terms: “If you had no head, no heart, no center of operations. If you could taste with your whole body. If you could take a fragment of your toe or your hair and it would grow into a new you—and hundreds of these new you’s could fuse together into some impossibly large togetherness. And when you wanted to get around, you would produce spores, this little condensed part of you that could travel in the air.”

That’s being a fungus. Simple, right? This means a journalist who wants to write about fungi, as I do at the moment, and also about other more-than-humans, must learn to live with permanent failure. If journalism demands you are able to reach the world that is the other, to reach another experience in being and becoming on this planet-home—something I’ve defended with all my teeth since I started out in journalism 35 years ago—in the case of fungi, this is (almost) impossible.

So the fact that the person writing is a journalist moving toward failure provides the reader with some relevant information. Journalistic coverage of more-than-humans is determined by our very body. Having this particular body, and not another one, substantially limits our experience in trying to reach other bodies, some of them radically different, like those of fungi. We would have to “myceliate” ourselves beyond what our lifespan allows. It’s possible an Indigenous journalist could reach much further, since Indigenous people inhabit their bodies differently, but it would still be quite difficult without help from the plant-being contained in ritual drinks like ayahuasca or without following other pathways of intersection between worlds. We will have to embrace these new tools for reporting if we want to produce better journalism on more-than-humans, capable of enhancing our ability to investigate other worlds by opening up parts of our consciousness that remain dormant unless stimulated.

Perhaps what we call “consciousness” isn’t enough, nor is our “unconscious.” We must expand the possibilities of both, mix them together. Perhaps it is only possible for us to listen to fungi and other beings through dreams, as the Indigenous understand dreaming. All of this involves profound negotiations with forest-peoples or, more interestingly, the whitening of traditional journalism and its protagonists.

Failure has been recognized. If you still want to enter this rainforest (and later travel down the mighty Xingu River) to read an honest story about this failure to listen to fungi, just come along.

Noemia is a mycologist, as fungus scientists are known. In the picture, she is collecting specimens in the Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve (INPA), in Manaus, Amazonas state. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

2. like Frida Kahlo

When I chose my subject for this magnificent series by Dromómanos, I didn’t know that fungi had become the Frida Kahlo of the natural world amid ruins built by humans. Everywhere you go in the West, you’ll find images of this brilliant artist. With her run-on eyebrows, piercing eyes, and bounty of colorful flowers, she has been converted into vases, penholders, T-shirts, and all sorts of trinkets. Frida is now pop, and fungi are starting to become pop as well. Fungi are cool. Although not where I live, in the rural area of Altamira, deep in the state of Pará, where I’ve spent months unsuccessfully trying to rid my four cats of a dermatophytosis caused by fungi of the genera Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton, who are advancing shamelessly over their bodies, leaving landscapes where hair once grew. But in the world of commodities, these creatures we generally only notice when they damage our toenails have in a way been “discovered” by a sophisticated audience capable of understanding what these beings represent on a planet with a mutating climate.

The aforementioned Merlin Sheldrake played a role in this popularization of fungi with his fascinating book Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape our Futures, released by Random House in 2020, in step with a publishing trend that has spotlighted plants and fungi. With the face of a Baroque angel and shyly charismatic personality, Sheldrake is now among the best-known authors in this new world that writes about some of the oldest living beings on the planet. But he’s far from the only one. In recent years, the number of books, films, series, and documentaries on fungi has grown almost as much as Frida Kahlo’s myceliant eyebrows.

In the legal field of the Rights of Nature, a group of scientists and activists has been working to defend fungi. In April 2021 they released the Statement of the Fauna Flora Funga Initiative: “It is time for fungi to be recognized within legal conservation frameworks and protected on an equal footing with animals and plants.” The best estimate, according to their manifesto, is that the planet has from 2.2 to 3.8 million species of fungus—from six to ten times the estimated number of plant species. But science has described fewer than 10% of all fungus species. To date, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has classified only 625 according to its Red List of Threatened Species, compared to 87,000 species of animals and 62,000 species of plants. Fungi, according to the Fauna Flora Funga Initiative, “represent a meagre 0.2% of our global conservation priorities.” Some mycologists view initiatives like this with caution. While it is tremendously important to protect fungi, these specialists feel care must be taken with the Red List because some species are essential to the diet of Indigenous peoples, while other species are used to make intricate baskets by people like the Yanomami in Brazil. Nothing better than debate so questions can enhance action.

This movement on behalf of fungi, the most neglected members of a neglected nature, is built on sound reasoning, like concerns over the very survival of the human species. The best science has demonstrated that more than 90% of plants depend on symbiotic fungi, who entangle with plant cells, guarantee plants essential nutrients, and defend plants from disease. These fungi are an older part of plants than are leaves, flowers, fruit, or even roots, and they lie at the bottom of the food chains that sustain much of life on Earth. Fungi are so fabulous that some species are able to live in mining tailings while others have proven resistant to radiation, with potential use in cleaning up contaminated areas.

Anthropocentrism—putting man (the gender choice is deliberate) at the center—has brought us to the climate catastrophe. It has also limited our view of everyone we call other. “Classical scientific definitions of intelligence use humans as a yardstick by which all other species are measured,” warns Sheldrake. “According to these anthropocentric definitions, humans are always at the top of the intelligence rankings, followed by animals that look like us (chimpanzees, bonobos, etc.), followed again by other ‘higher’ animals, and onward and downward in the league table—a great chain of intelligence drawn up by the ancient Greeks, which persists one way or another to this day. Because these organisms don’t look like us or outwardly behave like us—or have brains—they have traditionally been allocated a position somewhere at the bottom of the scale.”

Visiting the land of beiradeira Raimunda Tutanguira, in Altamira, Noemia observed this fungus of genus Tremella for the first time in her 30 years of work. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

This human body, however, in which we take such pride, is much more limited in its possibilities than any fungus, which should have become clear by this point in our narrative. “We can’t grow extra limbs, and we’re stuck with the one brain we’ve each got. In contrast, fungi keep growing and changing form all their lives,” writes the US anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing in The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press). Released in 2015, this book was an event. “Fungi are famous for changing shape in relation to their encounters and environments. Many are ‘potentially immortal,’ meaning they die from disease, injury, or lack of resources, but not from old age. Even this little fact can alert us to how much our thoughts about knowledge and existence just assume determinate life form and old age. We rarely imagine life without such limits,” writes Tsing.

Fungi challenge us to think differently, based on other possibilities opened up by other bodies and relationships between and among the diversity of beings. But since capitalism has formed humans who only perceive and respect anyone other than themselves if they know this serves some useful purpose, we should remember that fungi lie at the base of almost everything important in our daily lives, from bread and beer to the penicillin that continues to save millions of people’s lives every year. Fungi produce compounds currently employed in such medications as antibiotics, statins, and immunosuppressants. There is also research into the use of compounds derived from fungi in anti-cancer drugs, antiparasitics, antidepressants, and medications for other illnesses.

In short: if you have cholesterol problems, your chances of enjoying yourself at a meal are directly linked to fungi, and if you fall ill, your chances of a cure may also depend directly on this organism’s existence. So from the standpoint of human utilitarianism (or navel-gazing), it makes total sense to be concerned about the future of fungi. Like other beings, fungi are hit hard by deforestation, burn-offs, and the overuse of pesticides. Worrying about them is as important as worrying about new generations of humans, because without fungi there might not be a tomorrow for the children who are here today.

Expedition to the Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve, INPA, in Manaus, Amazonas state, in 2023: fungi of the genus Leucocoprinus. Photos: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

This is the fight being waged by the Fungi Foundation, with the support of scientists, people from the arts, and other personalities in Europe, the United States, and Latin America. The world’s first organization dedicated to protecting fungi, the foundation was established in 2010 by the Chilean mycologist Giuliana Furci. According to the website, this scientist’s work “triggered the inclusion of fungi in Chilean environmental legislation and made it possible to assess the conservation status of over 80 species of fungi.” Scientists and activities with the foundation “envision a healthy planet in which Fungi are recognized as the interconnectors of nature.” Its mission is to encourage research on fungi to “increase knowledge of their diversity, promote innovative solutions to contingent problems, educate about their existence and applications, as well as recommending public policy for their conservation.” A visit to the Fungi Foundation website is highly recommended, including a thought-provoking stop at the Fungipedia, where your most basic questions about fungi can be clarified—a starting point for a journey through an absolutely amazing universe of lives so different from ours, who not only sustain our shared home but also our very existence.

In collaborative association, we could echo the words of Merlin Sheldrake: “As you read these words, fungi are changing the way that life happens, as they have done for more than a billion years. They are eating rock, making soil, digesting pollutants, nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions, producing food, making medicines, manipulating animal behavior, and influencing the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere. Fungi provide a key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways that we think, feel, and behave. Yet they live their lives largely hidden from view, and over ninety percent of their species remain undocumented. The more we learn about fungi, the less makes sense without them. […] Many of the most dramatic events on Earth have been—and continue to be—a result of fungal activity. Plants only made it out of the water around five hundred million years ago because of their collaboration with fungi, which served as their root systems for tens of million years until plants could evolve their own. Today, more than ninety percent of plants depend on mycorrhizal fungi—from the Greek words for fungus (mykes) and root rhiza)—which can link trees in shared networks sometimes referred to as the ‘wood wide web.’ This ancient association gave rise to all recognizable life on land, the future of which depends on the continued ability of plants and fungi to form healthy relationships.”

Even human gastronomy wouldn’t be as sophisticated as it is without edible fungi. The matsutake mushroom, for example, weaves through Japanese culture; Japan as we know it wouldn’t exist without this mushroom. The journey of the matsutake is told in Anna Tsing’s extraordinary book, in which she myceliates knowledge to create one of the most original works of this new millennium. “If we open ourselves to their fungal attractions, matsutake can catapult us into the curiosity that seems to me the first requirement of collaborative survival in precarious times,” she writes in her prologue. “In a global state of precarity, we don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin.”

Tsing talks about being open to the indeterminacy of encounter and argues that precarity has the power to make encounters happen. “Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. […] Such indeterminacy expands our concept of human life, showing us how we are transformed by encounter,” she writes. Elsewhere in this masterful book: “We are contaminated by our encounters. […] Collaboration means working across difference, which leads to contamination. Without collaborations, we all die. […] The important stuff for life on earth happens in those transformations [of encounter and indeterminacy], not in the decision trees of self-contained individuals.”

Noemia holding mushrooms of the genus Favolus. The Yanomami consume species of this genus as part of their diet, such as Favolus yanomamii Palacio & Menolli, described in 2021 by Melissa Palacio and collaborators and named in honor of this Indigenous people. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

The US biologist Scott Gilbert has suggested that nature “may be selecting ‘relationships’ rather than individuals or genomes.” Opening yourself up to an encounter with fungi means understanding that the idea of the individual is an impossibility that could only take root in a system like capitalism, which wields control by alienating the others who are us—and by reducing us to one. At this very moment, it is only possible for me to write because of the bacteria digesting my breakfast. The bacteria in our body—39 trillion—outnumber the cells—30 trillion; the human intestine alone hosts more bacteria than there are stars in the galaxy. Fungi prove to us that the individual does not exist. There is no “we ourselves” without the others inside and outside us.

By weaving the living web of the world, fungi signal that life only exists through encounter. And encounters are always indeterminate.

3. Altamira, ruins of the forest

In Altamira, my habitat, the ruins of capitalism discussed in Anna Tsing’s book couldn’t be more explicit—and it is in the ensuant cracks that fierce resistance by everything alive also takes place. In a country given to gigantism, Altamira is Brazil’s largest municipality and also among the largest in the world, covering almost 62,000 square miles. The district of Castelo de Sonhos, for example, is part of the municipality of Altamira but is located over 600 miles from the municipal seat—quite convenient for the forest destroyers and their militias of gunmen who threaten and murder Amazon defenders and go unpunished. Lying off the beaten path for naturalists of the past and as big as some European countries, the municipality of Altamira is now a land of undiscovered wonders for scientists such as Noemia Ishikawa (a Brazilian, mind you), who says, “For me, Altamira is like a country I can look at just like naturalists in the past looked at Brazil.”

Brazil is home to 60% of the planet’s largest tropical rainforest. In this vast expanse, it is likely that no place represents the war on nature better than Altamira—a war waged by the dominant minority, formed of transnational corporations and the governments and parliaments that serve them, along with much of the superrich who are now building bunkers in countries like New Zealand to protect themselves from the climate cataclysm—or are trying to find a way to reach Mars. It was in the city of Altamira, on the banks of the Xingu, a highly biodiverse tributary of the Amazon River, that General Emílio Garrastazu Médici inaugurated work on the Trans-Amazonian Highway in the early 1970s. His official act was registered on a plaque that bespoke the all-too-human delirium of dictators: “On these banks of the Xingu, in the middle of the Amazon jungle, the President of the Republic has set in motion the construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, a historical step toward the conquest of this gigantic green world.”

Aerial photo of a swath of the Amazon forest in the municipality of Altamira, Pará state. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

To lend literal form to these words, a mammoth Brazil nut tree was chopped down, and the place became jokingly known as “pau do presidente”—the president’s wood. It is impossible to understand the destruction of the Amazon, or of any biome, without considering the impact of the patriarchy. The body of the forest has been violated for decades following the same logic that violates women; the body of the forest, like the bodies of women, treated as an object to be exploited—a body subdued, from which everything is ripped out so the exploitation can go on. The massive trunk of the chestnut tree, torn from the ground, then becomes the “president’s wood,” a phallic expression of the “conquest” of nature.

During the business-military dictatorship that oppressed Brazil from 1964 to 1985, it was under the presidency of General Médici that agents of the State kidnapped, tortured, and executed the largest number of civilians who were then resisting the quashing of democracy. Extra doses of sadism were reserved for the women who opposed the dictatorial regime, such as putting rats and cockroaches inside their vaginas; locking them up with a snake, which happened to the journalist Miriam Leitão; or bringing in their young children and showing them their tortured mother’s broken body, the case of Amélia Telles. “Mommy, why are you blue?” her 5-year-old daughter asked this woman who had been transformed by electric shocks.

The Trans-Amazonian Highway kicked off by Médici sliced through 2,500 miles of rainforest, decimating human and nonhuman original peoples. More than 8,000 Indigenous lives were taken under the dictatorship. Part of the road was built at the cost of blood and extermination. For the region of Altamira, this was the first end of the world.

The second end of the world occurred, paradoxically, under the most left-leaning government in Brazilian history, the administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, elected for two terms, from 2003 to 2010; since January of this year, Lula has once again been president of the country. This time, the name of the apocalypse is Belo Monte, a hydroelectric dam that blocked the Xingu River and turned Altamira into one of Brazil’s most violent cities as it drove thousands of people from the forest by drowning islands and devouring pieces of dry land. Development is “capitalism’s surname,” wrote the anthropologist Joana Cabral de Oliveira in her preface to the Portuguese translation of Anna Tsing’s book.

The region was so radically altered that in early 2020, shortly before the COVID-19 virus arrived there, the city witnessed a series of teen suicides. Mental health professionals hypothesized that the most likely explanations for the phenomenon were a breakdown in these people’s lifeway, a steady routine of violent death, and the annihilation of community ties occasioned by the hydropower plant, all of which had a greater impact on children who reached their adolescent years against this backdrop—the most fragile among the fragile, who watched the adults around them also be converted to ruins. Today, with the dam capturing 70% of the river’s water, the forest-peoples have accused Belo Monte of committing ecocide along the section of the Xingu known as the Volta Grande, an 80-mile-long stretch of immensely diverse rainforest with fish species found nowhere else on the planet.

Altamira often ranks first in records for deforestation and criminal forest fires in the Brazilian Amazon. In this context of continuous, persistent destruction of everything alive, including forest-peoples, it’s easy to understand why the need to protect fungi never crossed anyone’s mind for even a second. But it crossed Noemia Ishikawa’s, and there it stayed.

4. the fungus-human

Noemia, a descendant of Japanese immigrants who took up a life of farming in Londrina, in southern Brazil, fell in love with the shiitake mushrooms her grandfather Nobuo Komagome raised with the stubbornness of a survivor. When he emigrated to the other side of the planet in 1932, Nobuo was looking for adventure and a life free of poverty. He needed to make ties to make a home. Between the grandfather, who planted himself in a foreign land like the fungus ascribed so many meanings in his ancestral cradle, and Noemia, the child who was bullied at school because she differed in form and content, the shiitake was bridge, womb, and destiny.

In the forest in Altamira, Noemia observes fungi of the species Pleurotus djamor, one of the mushrooms that is part of the Yanomami diet. They call it Hiwala Amo, which means porcupine. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

From an early age, Noemia identified more with the trans-almost-everything vocation of fungi than with the humans she was forced to engage with outside her family home. She slowly grew to resemble a generous human mushroom in form as well, something that bewilders certain specimens of her original species. Noemia loves to write about her experiences in the form of crônicas, a Brazilian genre of short fiction or essays. In a creative writing workshop, she invented a character who was actually herself so she could talk about herself without the need for too much explanation. But when the candidate literati in her class analyzed her work, they declared her character “poorly crafted” and argued it was impossible for the same person to transit between such different universes of knowledge. They clearly understood nothing about fungi, nor about human others. Noemia often describes herself as “neither-nor”—neither a girl nor a woman, for example. In her opinion, neither-nor affords a fungal freedom that allows her to myceliate through life.

When she grew up, Noemia became a biologist and respected fungus scientist, with a doctorate from Japan. She migrated to northern Brazil and made her home at the National Institute for Research on the Amazon (INPA), a center for scientific production in the middle of a surviving rainforest in Manaus, among the most degraded, violent state capitals in the Amazon. At the time, in 2004, Noemia was following the rain. “When I decided to live in the Amazon, my plan was to live where it rained a lot, because there would be lots of mushrooms. The plan worked; I’ve had the opportunity to get to know hundreds of species of fungi and take part in the discovery of dozens of new species. Even on short walks after lunch, twice we’ve found species as yet unknown to science,” she says. “But something had always intrigued me: why do fungi use so much energy to produce disproportional amounts of spores, so that millions of tons of spores are dispersed into the atmosphere every year? I only understood this when I read an article by Maribeth Hassett and collaborators, published in the scientific journal Plos One and entitled ‘Mushrooms as Rainmakers: How Spores Act as Nuclei for Raindrops.’ The paper explains that spores, along with plant pollen and other particulates, can act as nuclei of water condensation in a cloud. So mushroom spores can promote rainfall in ecosystems.” Since then, Noemia has been grappling with another question, much like the famous chicken-or-the-egg conundrum: “In the Amazon, are there more mushrooms because there’s more rain, or does it rain more because there are more mushrooms?”

If academic science knows less than 10% of the planet’s fungi, the most likely hypothesis is that much of the remaining 90% are found in tropical rainforests around the world, centers of biodiversity on Earth. The largest of these is precisely the Amazon, now racing towards the point of no return, the moment when the destruction will have gone so far that the rainforest will stop being what it is and doing what it does to become something else.

The scientist Luciana Gatti, with the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), a leading center of science production in Brazil, has demonstrated in recent studies that, given the level of ruination, vast swathes of the Amazon no longer act as carbon sinks, instead emitting more carbon dioxide than they absorb. In these areas, the forest has thus gone from being a solution in the fight against global heating to being a problem. Luciana’s latest research, which involved some 30 investigators from various fields and was published this August in the journal Nature and SUMAÚMA simultaneously, showed that the first two years of the administration of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro, 2019 and 2020, impacted the forest as much as the worst El Niño ever recorded, in 2015 and 2016. There is strong evidence that Bolsonaro’s third and fourth years as president may have been even more catastrophic than the first two.

To the left, fungus of the genus Marasmiellus, in the Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve, INPA, in Manaus. To the right, fungus of the genus Xylaria, found on Gerardo Ferreira da Silva’s property, in Altamira, Pará state. Photos: Christian Braga and Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

This shows how little time we have to stop the accelerated destruction of nature. And even less time to grasp something not very well understood by most of the public and also by politicians, environmentalists, and even some climate scientists: the role of fungi in the Amazon, where they are the great creators and maintainers of the forest, sustaining it through their enormous mycelial network, Earth’s living weave. If the Yanomami, an Indigenous people currently victims of genocide, living between Brazil and Venezuela, call themselves the “people who hold up the sky,” fungi could perfectly well call themselves the “people who hold up the Earth.”

Because the region of Altamira lay off the route for the few naturalists who journeyed to Brazil in centuries past, coming mostly from Europe, Noemia was amazed when she visited a friend there in 2013. “I encountered such a diversity of mushroom species; I even found them on city streets,” she recalls. During her unpretentious travels over the following years, she was to discover two mushroom species she never saw elsewhere. Even for Brazilian academic science, the area was still a huge patch of ignorance about fungal diversity. Noemia then joined forces with other professors to establish a graduate program in biodiversity, based at the Altamira campus of the Universidade Federal do Pará.

Science has always been as colonizing as were European monarchies and the rising commercial bourgeoisie during their invasion of the Americas. So the scientists who documented genera and species of fungi in Brazil and the rest of Latin America were almost all European, with Eurocentric mentalities. Even today, no matter how politically correct and generally well-intentioned initiatives to protect mushrooms may be, the lead voices and best-selling writers in Europe and the United States have little real involvement with the Amazon scientists who conduct their work with scant resources, and in gunslinging land.

This is the case of scientists like Noemia, who are fighting for fungi in an Amazon where it is extremely challenging to keep forest defenders from being murdered by illegal loggers, landgrabbers, and mining bosses. Among their most fertile regions of investigation is the land of the Yanomami people, the largest Indigenous territory in Brazil, covering 37,500 square miles. Earlier this year, SUMAÚMA revealed the genocide underway inside their territory, prompted by the invasion of illicit gold miners that was encouraged by former president Jair Bolsonaro and counted on the involvement of at least one large organized crime group. During Bolsonaro’s four years in office, from 2019 to 2022, 570 Yanomami children under the age of five lost their lives to preventable diseases. Some of these small children passed away while vomiting worms that had found their way into their bodies through contaminated river waters, worms they couldn’t eliminate either because no medicine was available or because in some regions illegal miners had burned down the healthcare posts.

The artist Hadna Abreu, a SUMAÚMA collaborator, does illustrations of Noemia Ishikawa’s research work with fungi. Manaus, Amazonas state. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

In the Japanese language, Noemia points out, “the term for fungus (菌) is pronounced the same as the word for gold/money (金),” suggesting how values differ between cultures. “My Indigenous friends and I don’t understand why gold/money, a shiny, immutable metal that can’t be eaten, drunk, or used to make clothes, is worth more than fungi (菌), who have been generated by hundreds of millions of years of evolution and can provide nourishing food, be used to make beverages or clothing and to heal, and can delight us with their natural beauty and luminescence,” the scientist says in frustration.

Brazilian scientists need to work in contexts like the Yanomami territory, but they are often prevented from doing their research for months or even years because it isn’t safe there. Although Noemia does her research in regions of the territory less affected by criminal mining activities, it would be impossible for the violence not to reverberate there as well. A vision of naturalists conducting investigations in bucolic settings can only be cultivated by imaginations alienated from the brutal reality experienced on the frontlines of the war against nature. There is no salvation outside of political action, something a segment of the scientific community is still slow to comprehend.

If there are few resources for protecting humans themselves, then in a hegemonic culture that puts humans at the center of everything, it’s easy to imagine what is left even for charismatic species like turtles and dolphins, who also run the risk of disappearing in some regions. So then imagine what’s left for fungi, beings often viewed as aliens, the weirdos of the Earth, even though they have cocreated the planet.

This is how urgent things are for the fungi that weave life together on this planet—and especially for the vast world of fungi that myceliate the Amazon. Because of this pain, I watched Noemi’s eyes turn to water several times.

At the end of an expedition, researchers gather their collections in displays like this. In Altamira, while visiting the land of woodworker Gerardo Ferreira da Silva Filho, Noemia’s group collected 59 species of mushrooms. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

5. floor of stars

I met Noemia Ishikawa when she visited the community where I live, in 2021, during one of the first lulls in the COVID-19 pandemic. My partner, the journalist Jonathan Watts, and I had purchased a piece of degraded land on the outskirts of Altamira, where forest had been converted into cattle pasture. We were adding our forces to the dream of creating an enclave of resistance in an epicenter of Amazon destruction. The idea that drives this community is that each resident who comes to make their home here also makes a forest. So when we bought our piece of ruined land, Jon and I started with a muvuca, an Indigenous reforestation technique. We spent days digging furrows with small holes about three feet apart. When everything was ready, neighbors and friends, children and adults, joined us for the most extraordinary moment, the sewing of more than 30 species of trees, each seed a work of art in their diversity of shapes, hues, and sizes.

We wanted to gaze at these seeds for months, feeling their elegant bodies, before casting them onto the soil. No matter how well I might understand the mechanisms capitalism employs to achieve the accelerated corrosion of human bodies or to deform our feelings and thinking, a process that began when bodies were put up for rent and our insides shaped by consumption, I can’t help but be intrigued by how anyone can destroy a forest to obtain gold when we have in our hands these wonders that turn to forest. You scatter a seed on the ground, like birds, bugs, and bats do, and something alive is born there. And so it was, planting a small, tiny patch of forest, that we began to build our home.

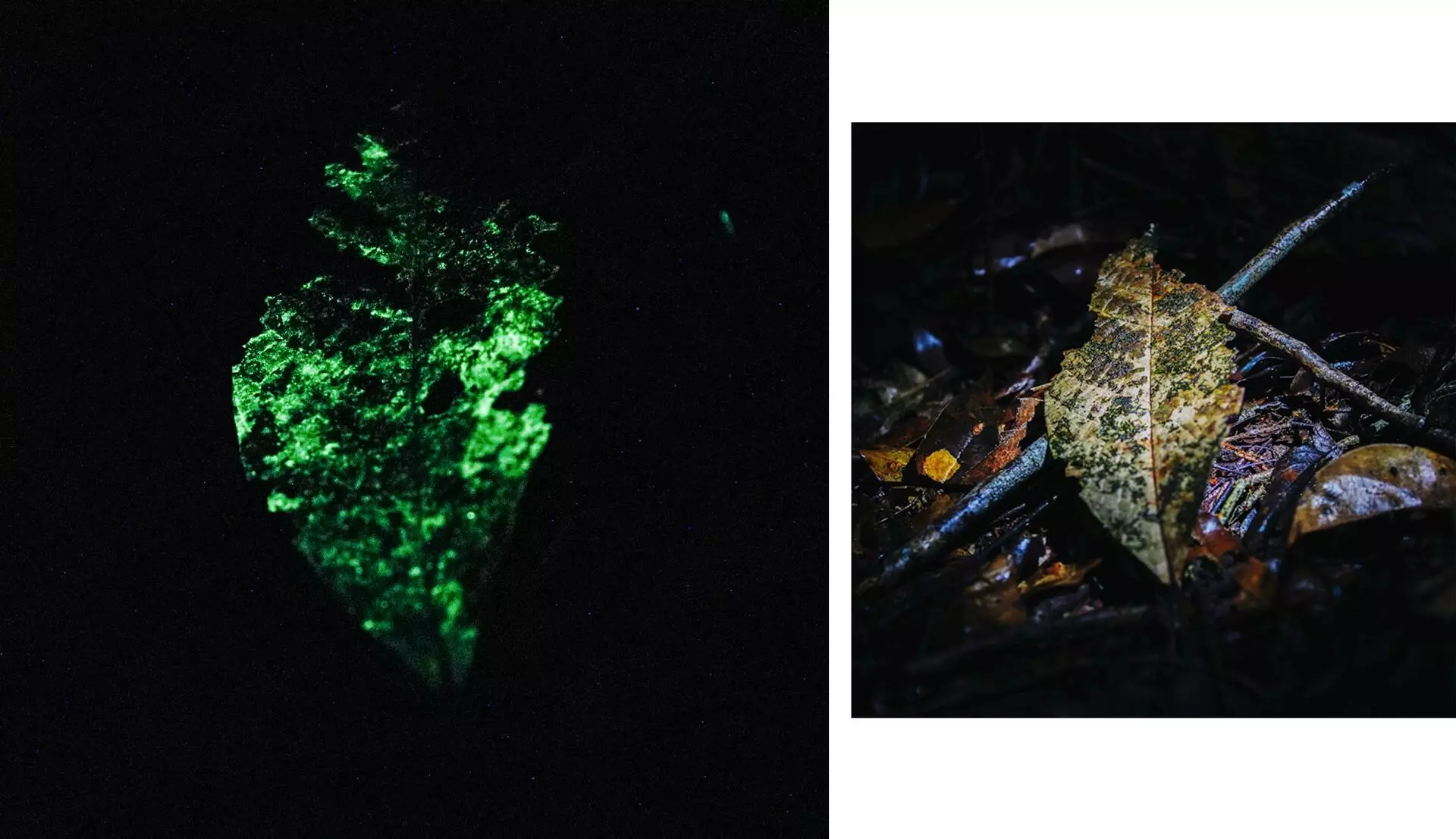

This was where Noemia first met us. The home was ours, but it was our visitor who took us to meet the neighbors. Early one evening, she escorted us on a walk around a small area of surviving forest, just a few dozen yards from our house. Once there, she told us to turn off our flashlights. It gives you a powerful feeling to be in the forest in the dark. In the pitch black. You become more deeply aware of your fragility when everything above and below you, everything beside and around you, is alive—not dead like in a city. We stayed like that, in absolute silence, for five minutes. And then, suddenly, a tiny light came on at our feet. And then another little light. And yet another. We remained there, still and quiet, watching the lights come on. Ten minutes later, I understood the expression chão de estrelas—floor of stars. As Brazilian composers Sílvio Caldas and Orestes Barbosa wrote in their song of this title, we have been “carelessly stepping on stars” for so long. There were stars all over the forest floor, on tree trunks, on bushes, on leaves. Imagine this: at night, the forest has a floor of stars.

My eyes floated in the beauty of it all. I held back sobs because I didn’t want to make noise in someone else’s home. Only then did Noemia explain that we were looking at bioluminescent fungi. They had always been there, right next to our house, but I had never noticed them. I had been passing by them several times a day but had never, ever been capable of seeing them.

I’m telling you about this scene because I think this is what happens with non-Indigenous humans and the Amazon forest—or any other enclave of nature. There is what we see, which is almost nothing. There’s what we know is there, because someone researched it, which is a little more, but still almost nothing. And then there’s what we don’t know to be there, which is almost everything.

The same leaf photographed two ways: on the left, in the total absence of light, covered with bioluminescent fungi; on the right, shown with lighting. These photographs were taken in the Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve, INPA, in Manaus, Amazonas state. Photo: Christian Braga/SUMAÚMA

There’s an expression often applied to the Amazon and other biomes that can also be applied to fungi and everything unknown to humans: to know you is to love you. This is supposedly why we should make a monumental educational effort to share knowledge about the Amazon and its inhabitants with the greatest possible number of people, as a strategy for their conservation. Personally, I disagree. I do think this monumental educational effort would be great for humans, who would thus have a chance to broaden their limited view of themselves and the worlds around them, beyond their own navels. But I don’t think it’s necessary to know the other to love them, and much less to know and love the other in order to respect their life.

Think about the fungi and all the peoples we ignore in our ignorance. If this exercise is hard, think about those who are curiously called “isolated peoples,” the Indigenous who have concluded that their lives are much better without knowing non-Indigenous or even other original peoples. The planet’s largest concentration of isolated peoples lies in the Brazilian Amazon, in Javari Valley, where they endeavor daily to live without crossing paths with any whites. They don’t want to get to know us—and we don’t need to get to know them to respect them. We only need to respect them, which means respecting their decision to continue not knowing us. It’s that simple. It’s very arrogant to think that for everyone else to have the right to exist—peoples or territories—they need the approval of our magnanimous love.

Noemia says that Takehide Ikeda, a scientist with Kyoto University who researches the colors of living beings, once told her: “Half of the world is always dark, but people only look at the light part.” This comment got Noemia to thinking about how much we tend to associate the unknown with darkness and the known with light. And how humans try to illuminate more and more places for longer and longer hours at night—as is apparent from the screens flashing away on seatbacks during overnight flights. Noemia was pleased to point out how dark the Amazon still is on these maps at night.

“On the ground in the Amazon, entering the forest at night, especially under a new moon, is an experience I’ve never grown tired of. We call this ‘nocturnal mycotourism,’” she says. “We usually see leaves emitting light but on rare occasions it’s possible to find a whole mushroom aglow.” What seems new to most people was actually reported by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) and the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE), both of whom observed that damp wood sometimes gives off a sheen. Today we know this glow comes from bioluminescent fungi who are decomposing wood. Bioluminescence is a phenomenon involving light-emitting organisms that was first registered in poetry, illustrations, stories, and even fables but is now studied by researchers the world over.

The Irish chemist and physicist Robert Boyle (1627-1691) showed that oxygen is involved in the process of bioluminescence in both fungi and fireflies. Two centuries later, the French pharmacist Raphaël Dubois discovered that the chemical reaction of bioluminescence requires a heat-stable molecule, which he called a luciferin, and a heat-unstable molecule that he believed was an enzyme, which he called a luciferase. With the scientific advances of the 20th century, research proved both Boyle and Dubois right. During the latter part of his life, Osamu Shimomura (1928-2018), a Japanese Nobel prize winner, focused on the bioluminescence system of luminous fungi. An international research team, with representatives from Russia, Brazil, and Japan, finally elucidated the whole matter in 2017. In Brazil, the team was led by Cassius Stevani, with the Chemistry Institute at the Universidade de São Paulo. To date, 115 species of bioluminescent fungi have been documented, 20 of them in Brazil. Two species have been reported in the Amazon: Mycena lacrimans and Mycena cristinae.

The person who revealed the glow of fungi to Noemia, one night in the rainforest in 2017, was the Indigenous man Aldevan Baniwa. Aldevan, who was an Indigenous healthcare agent specialized in endemic diseases, would die three years later, on April 18, 2020, from COVID-19, at the age of 46. While he was caring for the ill, the State had provided him with only one mask a day. More than 700,000 people died of the disease in Brazil during the pandemic, when the Bolsonaro administration carried out a plan to spread the virus to achieve “herd immunity.” For Indigenous people, things were worse yet: Bolsonaro even vetoed access to drinkable water, the installation of emergency beds, and a prevention campaign in Indigenous languages, vetoes later overridden by Congress. When the vaccines came on the market, he mounted a crusade against them. Lacking access to basics or to protective barriers, leaders like Aldevan and dozens of Indigenous elders who were the roots of their communities and guardians of memory and language died of COVID-19. One of them, Aruká Juma, was the last of his people.

A fungus found inside a cocoa shell on the land of Raimunda Tutanguira, in Altamira, Pará. Researchers have not yet identified the fungus. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

When Noemia discovered bioluminescent fungi, she was so excited that she co-authored a book with Aldevan Baniwa, Takehide Ikeda, and Ana Carla Bruno: Lights in the Forest (Inpa and Valer, 2019). The book inspired other works of art: the singer Ellen Fernandes composed the song “Luzes da Floresta” (Forest lights), the artist Hadna Abreu put together the exhibit Amazônia ao cubo (Amazonia to the 3rd power), and Cíntia Moreira told the story in narrative verse, in the form of folk art known as cordel literature.

“The fungus colonizes the leaf and as a result, it glows at night. Aldevan took me and Ikeda to see this. That’s the book’s story. We explore the irony of how scientists always want to enlighten, but Aldevan taught us we have to turn our flashlights off and stay in the dark to see what we need to see. It was ironic that scientists had to turn off technology to see what they needed to,” Noemia tells us, since Aldevan Baniwa can no longer tell us anything. “The book also narrates the story of Aldevan’s relatives, who got lost in the forest when darkness fell but managed to get back to their village because the glow of the fungi showed them the way.”

Noemia is one of those rare scientists who truly myceliates with the communities where she works; sometimes the Indigenous call her in just to cook for them. She is among those who fight so forest-peoples can occupy universities and have their knowledge seen as science. She gathered a team of translators of various Indigenous languages to translate books like Lights in the Forest from their original Portuguese. But when it came time to digitalize the translations, she ran into a common problem: certain characters are missing on the conventional keyboard, like ɨ, ʉ, and letters with more than one accent, such as ë̃. She convinced two young people from Manaus, Samuel Minev Benzecry and Juliano Portela, to devise a keyboard adapted to Indigenous alphabets so the languages could be written and translated more easily on the computer. This invention that connects words-worlds was dubbed a Linkboard.

Stepping on stars and sharing many ideas, Noemia and I have myceliated on numerous occasions in our lives ever since she taught me I need to hold onto darkness to be able to see. When this report began taking form, I asked her and Flechinha to be co-authors with me, splitting the fee equally, because it would be impossible to do a story on fungi unless it was by myceliating—even though with humans.

6. arrow-man

Francisco Marques Bezerra, better known as Flechinha—Little Arrow—is what scientists usually call a “woodsman,” or “informant.” As has already been made clear, European and US scientists generally have primacy over their Brazilian and Latin American colleagues, because the former benefit from substantially greater funding and resources, thanks to the historical accumulation of capital at the expense of nature and of the bodies of Indigenous and Black people in the southern half of the world.

Francisco Marques Bezerra, forest scientist and co-author of this story, was part of the team that found and registered the luminescence of the first species of bioluminescent mushroom identified in the Amazon: Mycena lacrimans. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Researchers like Flechinha are at the bottom of this highly predatory, unequal food chain. Earning a daily wage of around USD 30, just above hunger level, they are the ones who locate and open trails to places where scientists can find fungi and all their other living “objects” of study, they are the ones who know where these beings are located, and they are the ones who keep experiments running while the scientists are back home, enjoying the perks of life at traditional universities and lecturing to their peers on the dangers they faced in the tropics. The science of people like Flechinha isn’t recognized in most academic papers or scientific discoveries; on the few occasions when they are cited, it is as an “informant.” Science production is still a territory of vast colonial exploitation and much surplus value. But Flechinha knows who he is. “I’ve trained many PhDs, here and abroad,” he says.

This scientist of the woods works in all areas: birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, insects, fungi. In the area of fungi (which isn’t actually his favorite), he was part of the team that found and recorded the luminescence of the first species of bioluminescent mushrooms identified in the Amazon: Mycena lacrimans. In fact, Flechinha was the first to spot the shining mushroom. But it’s not his name that’s remembered.

Following a trend initiated in previous years, science funding was slashed under Bolsonaro, and this hit Brazilian scientists hard. If academic researchers were affected, even more so people like Flechinha, who don’t have a steady job or other guarantees. It was very difficult for him to survive during this period. “In the area where I work, things get tougher in the winter [the rainy season]. But things got even tougher under Bolsonaro because he really cut research funding. I took odd jobs painting houses to survive,” Flechinha reports. A group of researchers from Manaus passed the hat so Flechinha and other woodsmen wouldn’t go hungry, but it wasn’t enough. Born in Altamira, Flechinha spent eight years in Manaus unable to travel to his hometown to be with his children. He only saw his family again when he did the fieldwork for this story.

His nickname, Flechinha, as he is known in the academic world, comes from his agility and speed in the forest. He once ran more than 18 miles through dense woods to seek help when someone was seriously injured with a chainsaw and needed medical assistance to keep from losing their leg. Francisco became Flecha—Arrow. Later, he became Flechinha—Little Arrow—since people in Brazil express their affection through diminutives. Flechinha earned a well-deserved reputation as the fastest of the woodsmen and is much in demand for those researching speedy animals, from reptiles to birds.

Flechinha: he once ran more than 18 miles through dense woods to seek help when someone was seriously injured and needed medical assistance to keep from losing their leg. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Noemia was stuck on a long waiting list to secure a few days on Flechinha’s schedule; this was well before cuts to research funding put most field investigations on hold. “We clicked right away. I liked him a lot and started scheduling my collection work to fit in with Flechinha’s availability,” she says. A while later, the INPA secretary who organizes the woodsmen’s schedules told Noemia her fellow researchers were complaining that she was monopolizing Flechinha; they said she didn’t need such a fast woodsman because “mushrooms don’t walk.” Noemia sent the whiners a message: “I’m chubby, not physically fit, and I have a torn meniscus. So if there’s a problem, I need help fast.” Thanks to Flechinha’s expertise in the rainforest, the two of them have never faced any danger. Together, they have collected hundreds of mushrooms and welcomed visitors from Brazil and other countries who come to meet the fungi of the Amazon.

Before our treks through areas of forest in search of fungi, Noemia and I would always stop at the invisible gateway into the woods, where she would ask permission to enter someone else’s house: “We ask your permission to come in. Show us what you want to show, and hide what you want to hide.” I suspect the forest wanted to show itself to us because even in small areas of urban Altamira, like Gerardo Ferreira da Silva Filho’s half-acre yard, we found 50 species of fungi. Gerardo has an arresting, somewhat unique personality: he is a woodworker who can’t bear to cut down trees anymore, so he has begun fashioning doors, window frames, and furniture from small pieces of salvaged wood glued together. And he raised a huge dog not even he can control, almost a hellhound, who he threatens to let loose whenever some hunter asks permission to shoot at living creatures in his yard. He’s a champion runner in his age category in Altamira, where he participates in events like the 10K in honor of the city’s patron saint, Sebastian.

One of the fungi we found in Gerardo’s yard is a member of a new genus discovered by the scientist’s team in 2019. The scientific name is, as usual, designed to be unpronounceable: Pusillomyces. We prefer to call it “Noemia’s hair” because it is very fine and very black. At least 176 bird species around the world use similar fungi to make their nests. “Since fungi continue to release antimicrobial compounds, this helps keep the nests freer of bacteria and safe for the babies,” says Noemia. “This partnership between fungi and birds, on the one hand, helps birds in their evolutionary success, while on the other it helps spread these fungi through the forests.”

In doing this story, I relied more on Flechinha than any other human in my endeavor to listen to another species with a body so different from mine. Noticing my visible anxiety, he told me very gently, “You won’t be able to listen.”

Then, distressed by my distress, he explained: “The whole forest has life, and everyone here has feelings. But you can only listen to the forest in silence. You look at a plant, and she shows you something. Then you look again, and she shows you something else. Every time you look away and then look back, you’ll see something different. It’s a response, just like smells and things entangling.” Flechinha took a few swift steps into the woods and shot back like an arrow to add: “The tongue, it pronounces everything, but our best vision is inside our minds. If you think a certain place is pretty, it’s because someone in the forest is responding to you.”

I understood what Flechinha was telling me, and I believe I listened to something in the forest at least once, although I don’t think I managed to fully grasp the message. I would later read in Anna Tsing’s book, in reference to the matsutake mushroom, “Smell, unlike air, is a sign of the presence of another, to which we are already responding.”

Early this October, I met Giuliana Furci at the More Than Human Rights (MOTH) conference, between volcanos and Nothofagus, in Chile, and she told me she “feels” fungi. One night, she and Merlin Sheldrake were in this same region when they suddenly felt this communication between worlds and immediately stopped their car. They came upon a blue mushroom. I asked her what she feels when she listens, and Giuliana explained that it’s something that runs through her body.

Entering a forest is an experience in being observed from all sides and angles without being able to see who is observing you. It is also the experience of feeling engulfed by a living being, who breathes and touches you in all sorts of ways. It’s almost like overdosing on life, and it always impacts my body for weeks. In the dark, this kaleidoscope of sensations is even greater.

We were wearing dark clothing on this new moon night because light-colored clothing interferes with the contemplation of bioluminescent fungi. We had been there for a couple of hours when I picked up a chunk of wood that was glowing all over. At that moment, I felt like the linguist in the movie Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016), the character played by Amy Adams, who was trying to figure out what the aliens were saying on their visit to Earth. I felt deeply connected to that other, and somehow I feel the fungi are here right now, inspiring me to write this text, because the experience of searching for them changed me. The precarity of what I call “I” led me to find them, and so they are here with me in some way. I will never forget what I felt and what cannot be put into human words. But something happened between us—or so my desire leads me to believe.

And then we had to rush out of the forest because we heard the sound of paca and armadillo poachers—and they are armed.

7. collapse

Flechinha was born on the islands of the Xingu, his father a fisherman and his mother a seamstress. Whenever he could, he would snuggle down inside the canoe before sunrise to paddle the river in the mornings. His father would later row two hours to the city and another two hours back so his children could go to school. At the end of the day, he repeated the journey. Flechinha’s parents fortunately lived long enough to know their son became a trainer of PhDs in various languages.

Flechinha’s family lived on Pedro Alves Island—not to be confused with Pedro Álvares Cabral, the Portuguese navigator responsible for the invasion of what would one day be called Brazil and a collaborator in what would become the extermination of more than 90% of the original populations in some regions of the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, killed by the viruses and bacteria that crossed the ocean aboard these men’s bodies. The Pedro Alves of the island where Flechinha’s family lived was not the protagonist of any act of genocide; he was just the first non-Indigenous inhabitant there. On the Xingu, as on other Amazon rivers, islands became the last possible territories for the migrants who arrived, but not without conflict with the Indigenous peoples who were their original inhabitants.

Noemia Ishikawa reaches the place where she discovered two new species of fungi in 2019. There used to be an island here, south of Altamira, but it disappeared because Belo Monte altered the flow of the Xingu River. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Like so many poor Northeasterners, Flechinha’s father had left behind the droughts of his arid native state of Ceará to migrate to the Amazon rainforest, drawn by government programs seeking workers to extract the milky sap of rubber trees so the product could then be transformed into tires and other parts for cars and tanks during World War II (1939-1945). These workers were called “rubber soldiers.” Flechinha’s grandmother would rather her son face the forest and Indigenous people than serve as cannon fodder in Europe, fighting a war that wasn’t theirs. When it was all over, Flechinha’s father settled into one of the islands and started making a family and a life for himself, possibly overwhelmed by so much water and so many fish.

Flechinha hadn’t been back to his island for more than eight years, and that’s why we decided to make an expedition to his childhood home, so he could see it again, now with the eyes of a scientist. We were eager to discover how many fungi, in so many shapes and species, he would find back there. Flechinha, who is generally quite reserved, began jabbering away as soon as our motorboat headed down the Xingu. It was as if a swarm of memories emerged like yellow butterflies from within him, as he recounted a whole life determined by the island and the river’s moods.

Noemia, the photographer Alessandro Falco, the helmsman Romário Barros dos Santos, and I were suddenly transported into the universe of Flechinha’s childhood: his life with his neighbors and their weekend soccer games; the dreams of his seamstress mother and fisherman father; the little boy Flechinha, who would climb out of his father’s canoe with a wooden pole slung across his shoulders, the morning’s catch hanging there, as he set off down the streets of Altamira, hawking snappers, curimatãs, and tucunarés until time later that day, when whatever fish were left would be donated to the poorest.

The expedition was a gift Noemia had planned for Flechinha, with my complicity. After taking him to the territory of his childhood, we would proceed to another island where Noemia had found two new species of mushrooms in 2019. The night before, however, she dreamt a dog bit her on her right hand; she felt intense pain and the warmth of blood dripping down her fingers. In her dream she thought: “This is the hand I write with! I can’t pull it away because it’ll be ripped off. I have to bear the pain.” In the next act, Noemia herself was inside the dog’s mouth, struggling to get free. Then she realized the dog’s teeth were hollow and rotten, easily broken, so she snapped them off one by one, until the dog’s entire head had been ripped apart.

In her time with the Yanomami, Noemia began paying closer attention to dreams, a topic that is part of early morning hours in their Indigenous communities. A friend named Resende Maxiba Apiamö, a Yanomami from the Sanöma group, taught her that if a dream is good, you shouldn’t tell anyone until it happens, but if the dream is bad, you should tell at least three people and then maybe it won’t come true. That morning her dream wasn’t good, and yet Noemia didn’t share it with anyone. She left the hotel in a rush, planning to put her boots on in the boat once we arrived at the islands.

Over the years, when Noemia and Flechinha embarked on expeditions in search of fungi, the forest scientist would always get excited when he talked about his island, “a paradise with long sandy beaches, trees of all kinds and sizes, birds of so many colors.” We knew the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam had disfigured the landscape, drowned many islands, and chomped off big pieces of terra firma. I can’t explain why none of us suspected the same might have happened to Flechinha’s childhood.

It was only when he suddenly fell silent that we understood what we had done. “This was all forest here. That was all forest over there… There’s nothing left, it’s all gone.” He kept repeating this over and over, until falling silent. All around us stretched clumps of drowned trees, their withered branches reaching up to the sky as if in prayer. Not a graveyard but a holocaust of trees. Hundreds of tree-persons murdered, dying and emitting carbon dioxide as they did so.

Flechinha attempted to visit his childhood island in Altamira but when we arrived, we saw it had vanished in the flooding caused by Belo Monte. A single species of fungus (as yet unidentified) was found on this drowned tree. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Flechinha’s island-childhood no longer exists. There was nowhere to land because there was no land. The entire landscape that documented his family’s life had turned to water. Flechinha found himself lost.

Noemia began to feel sick to her stomach. She cried with regret for the pain and suffering she had caused her old friend. She wanted to say something but couldn’t. “What I really wanted to do was scream. The pain and my urge to scream were just like the dog bite in my dream, those groves of dead trees like the dog’s teeth I had to break,” she confided to me later. “I felt sad down to my feet, which seemed to cry like a child who can’t go where she wants when she wants, my helpless feet, no reason to put on my boots, because there was no ground to walk on.”

Flechinha started pointing out islands that didn’t exist anymore, that weren’t even ghosts because they had been swept from the world. In deadly silence our boat headed to the island of Camassu, where Noemia had collected the two new species, Scleroderma camassuense and Scleroderma anomalosporum. At the time, her team was already concerned about the future of ecosystems violated by the dam and had entitled their paper “Discovery or Extinction of New Scleroderma Species in Amazonia?”.

On our way, Flechinha was quiet and Noemia, sick. She started the exercise her psychologist had taught her for moments of conflict between her inner and outer worlds. While our boat traveled the dead waters of the Belo Monte reservoir, Noemia had the task of returning to an emotional situation from her past to remember how she had overcome it. If her choices had led to a positive outcome, then she should take the same path; if the result had been negative, she should do otherwise.

“My memories took me back to the day I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Just like now, I had gone into the museum without preparing myself emotionally. I literally couldn’t stand it there. I felt really sick and wasn’t able to see things to the end. I walked to where there were various melted watches all stopped, marking the same time. And it’s like my heart stopped there too,” she says. “They had to help me out of the museum, and that night I had a fever of nearly 104o. It felt like a good, innocent part of me vanished that day. I was ashamed to be a human that day. I felt the same way when I saw the flooded islands and groves of drowned trees all over the Belo Monte reservoir.”

When we reached the place indicated by our GPS, we discovered that Camassu Island had also drowned. And with it, everything that had once been alive. Like the fungi.

In the forest, we learn that silence only exists when there is death. This was the silence on our boat as we returned to Altamira along dead waters now home to a holocaust of nonhumans. Invisible parts of the humans who sailed the river also died there, inside Flechinha and Noemia. Then Noemia spotted a giant tree with an enormous gash in it. “Like a raped vagina,” she said. “I want to do things differently from when I fled the museum in Hiroshima. I want to handle this situation better. I want to see the tragedy through to the end.” We slowly rowed into a grove of squalid trees, the sound of the boat’s motor cut off. “The silence of absent life is terrifying,” whispered Noemia. “A perfect, ready-made setting for the end of a movie about any story that didn’t work out. People always ask me why I travel so far to do my research, but what I’m always trying to do is get away from the ruins. Nature, for me, is non-ruin. And then this.”

I would have liked to tell Noemia that, according to reports, the first living being to emerge from Hiroshima after it was obliterated by an atom bomb was a matsutake, but I didn’t know that yet. Noemia tried to crawl inside the ravished tree, to be embraced by that other body. She would later tell me all she wanted to do right then was return to her mother’s womb. And maybe that way she could be reborn. But when she attempted to burrow into the tree, she slipped and almost fell into the river, breaking the somber mood created by this tragically psychopoetic image. Flechinha, silent until then, burst out laughing.

In the face of collapse, life asserts itself once again.

***

Eliane Brum is a writer, journalist, and documentary filmmaker. She has published nine books, eight of them nonfiction, including Banzeiro Òkòtó: The Amazon as the Center of the World and The Collector of Leftover Souls: Field Notes on Brazil’s Everyday Insurrections. One of Brazil’s most award-winning journalists, she received the Maria Moors Cabot Prize from Columbia University for her body of work in 2021. Her books have been translated into English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Polish, Bulgarian, and Mandarin. She is the creator and director of SUMAÚMA. She lives in Altamira, Middle Xingu, in the Brazilian Amazon.

Noemia Kazue Ishikawa is a mycologist (fungus researcher) and writer of short stories and children’s and young people’s literature. She holds a doctorate in Natural Resources from Hokkaido University in Japan. She was born in Londrina, in the state of Paraná, and has lived in Manaus, in the state of Amazonas, since 2004. Noemia works at the National Institute for Research on the Amazon (INPA) and heads the Amazon Mushrooms Research Group.

Francisco Marques Bezerra, known as Flechinha, is a woodsman and field research assistant. Originally from Altamira, in the state of Pará, he has lived in Manaus, in the state of Amazonas, since 1989, where he works mainly with scientific projects conducted by the National Institute for Research on the Amazon (INPA) and Universidade Federal do Amazonas. Flechinha’s focus is on studies of fauna, flora, and fungi in the Brazilian Amazon.

This story is part of the Colapso project by Dromómanos, an independent news producer based in Mexico.

About Dromómanos

Dromómanos is a producer of independent journalism that investigates, educates and experiments to tell the story of Latin America in collaboration with journalists from all over the region. The project began in 2011, when its founders Alejandra S. Inzunza and José Luis Pardo Veiras traveled across the continent in a third-hand Volkswagen Pointer in a bid to forge a new journalistic model of continental coverage. Together they have created more than 20 long-form reportages and Narcoamérica, a book documenting the impact of drug trafficking on everyday life in societies throughout Latin America. In the past 12 years, Dromómanos has worked with over 100 contributors and partnered with 60 national and international media outlets to address the most pressing issues for Latin Americans, such as violence, the climate crisis, authoritarianism, migration and corruption.

About the Colapso project

What happens when the power of nature intersects with human suffering? In few places can one find a more striking answer to this question about our present and future than in Latin America, the most disparate and one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. Colapso (collapse) ventures deep into the jungles, mountains, islands, forests, deserts, oceans and cities of the region, to report from the field on the symptoms and consequences of the climate crisis.

Report and text: Eliane Brum

Research: Noemia Kazue Ishikawa e Francisco Marques Bezerra

Photos: Alessandro Falco (Altamira, Pará), Christian Braga (Manaus, Amazonas)

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquiria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Visual editing: Lela Beltrão

Editorial workflow, copy editing, and layout: Viviane Zandonadi (with Érica Saboya)

Near an island that no longer exists, south of Altamira, Noemia contemplates how Belo Monte has impacted the Xingu River, causing the disappearance of fungi she will never be able to know. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA