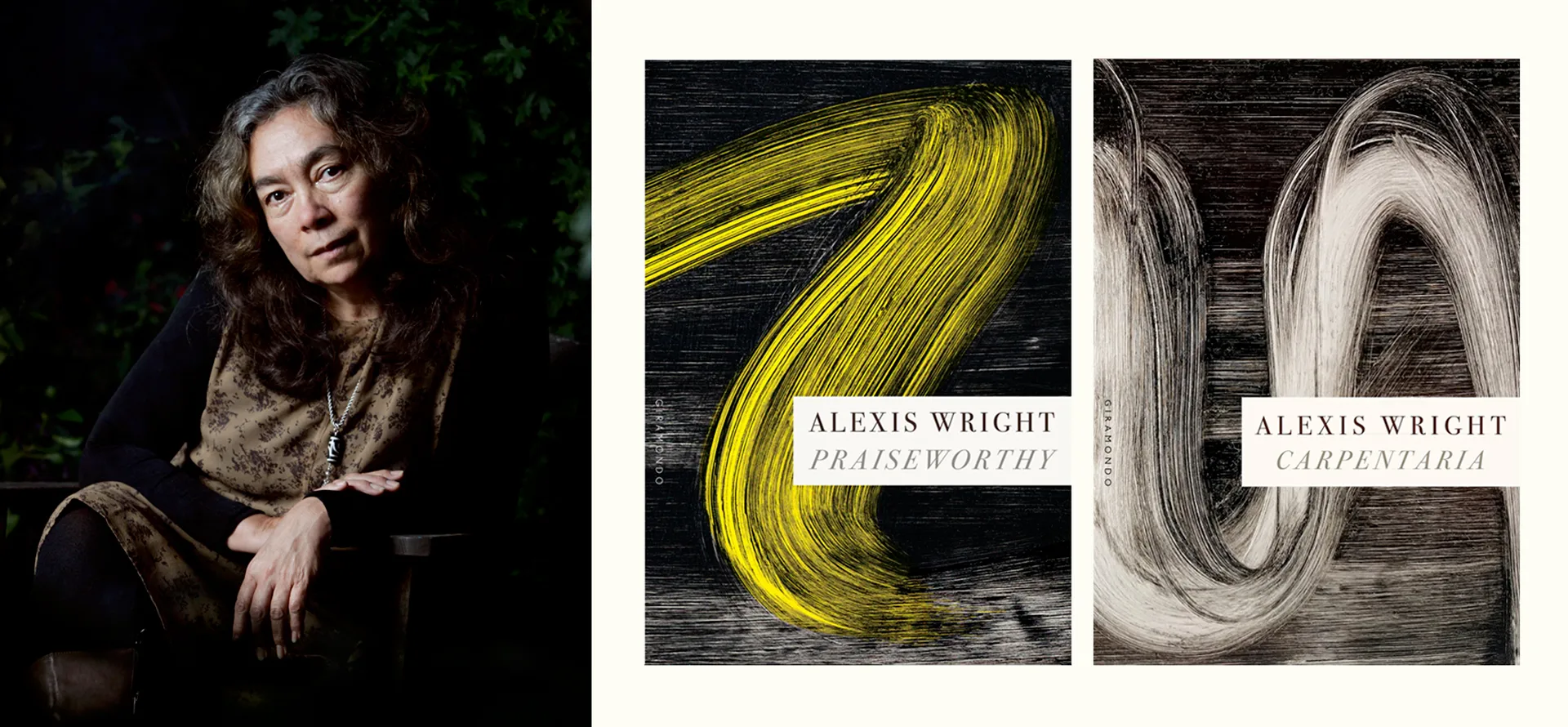

“To write for the future, as though your life depended on it, is to write hard,” says Alexis Wright, the Australian Aboriginal writer and author of Praiseworthy, a novel that introduces an unusual narrative in almost 700 pages of poetry, tenderness, freedom and rage. Wright, a member of the Waanyi people, grew up in northern Australia listening to her grandmother: “She instilled in me that I should be open to receiving ancestor wisdom.” Praiseworthy is a spectacular example of that wisdom, gained during Wright’s years of traveling and working in Central Australia as a rising star among the country’s great authors, who has received countless awards since she wowed readers with another novel, Carpentaria.

“I now live in what is called the green wedge of outer Melbourne surrounded by eucalypt and wattle forests. I am an outdoors person, and I like to be outside, and I often work and write outside every day.” A consequence of that life is this book in which five million donkeys, countless butterflies or the sea invite us to change our perception of the world. To ask ourselves about cultural sovereignty, wildness, speed.

It made sense in writing Praiseworthy to think off-key, in the style of the slow-beat yidaki, (also known as the digeridoo) clapsticks, ceremonial singing to match the repetitive rhythms of country, the one heart-beat. And to use an Aboriginal chord, to re-write any official narrative with the every-day brain-fueled humor found throughout the Aboriginal world. “The initial ideas for the book arose from asking very simple, but nevertheless huge questions about what might happen in the future of our peoples and culture on this continent. The fate of our people seemed similar and tied in many of the same ways to the lives of the global poor, the poorest people on Earth, the first people being oppressed across the world, and who will continue to be the first affected in any collapse of the world.”

The author, who is an Aboriginal Waanyi, grew up in northern Australia under the teachings of the ancestral wisdom passed down to her by her grandmother. She rose to fame with her novel Carpentaria

LITERNATURA – Donkeys are the trigger for a key idea in the novel. What is their presence in Australia today? If they are no longer used for agricultural work, what has been done with them?

Alexis Wright – It is known that across Northern Australia there are five million feral donkeys. Originally, they were introduced in early colonial Australia as pack animals, along with camels, both being hardier to the extremes of the local climate and geography than horses. Donkeys are extremely hardy, and have survived well in the arid environments of Australia. With the introduction of motorized transportation early in the 20th century, meant that many of these animals were released, or abandoned. They have roamed freely ever since and have grown into large populations in remote parts of the North. Feral donkeys have generally been regarded as pests causing environmental damage, and damage across pastoral land. Eradication programs have included shooting at these animals from helicopters, and sterilization. Although now, with more research, it is thought that the donkey’s ecological niche may correspond to—and benefit—the natural ecosystem from having replaced extinct Australian megafauna.

Why did you choose donkeys and butterflies as the key species in the story?

I love all creatures in the natural world. Why butterflies? The world spins its own vibrancy, and the infinite strength of this creative energy shines everywhere. Such is its enormity – stretching beyond our capacity to fathom and eclipsing the troubles of humanity. It is difficult not to see this. But we are caught up in the mighty ocean we have made of our own lesser-ness. So why not attempt to write into the borderless possibilities continuously endowing the world with their radiance? Why not try to cling to the willowing curtains flying in the wind through the ruptured walls of thought, or even just try to see further into the rapture of say, the hopping mouse moving through its ancestral pathways, butterflies in their flight patterns? Or why not let ourselves be illuminated by moths, try to travel with beetles, feel the tilt of collapsing trees, or see the trails of a lightning field, feel the power traces of spiritual ancestors, the pulse of travel through the countryside, without fear of losing our way back?

One of the main characters in Praiseworthy is someone we might call a culture dreamer who is obsessing about the era – global warming. And he knows that poor people like himself, or his people, cannot depend on anyone else e.g. Australian governments, to help them to survive. But we are not isolated from each other. We are all interconnected. We are all related, we are all dependent on the same planet for our survival. So this character –known by his people as Cause Man Steel, Widespread, or Planet– becomes obsessed about how his people and the wisdom and laws of their culture, this old culture, will survive in future times of global uncertainty. He reasons that Aboriginal people have survived here in their own country for millennia, and the way they had survived was not by sitting around and hoping things will turn out for the best. How did they do it? They desired survival. Widespread comes up with a plan by using nothing but his own brain power and very little resources: to use Australia’s five million feral donkeys to develop a major transport conglomeration fit for the new era. An era without fossil fuel. Without Qantas. It is a plan fraught with many difficulties, least of all, the deeply felt dislike for donkeys by his own people.

Widespread searches for the donkey God following Dreamtime, or the Dreaming, the moment of creation. What is the importance of dreams among Australian Aborigines today?

Australia is totally crisscrossed by the ancient law stories of the creation ancestors. These powerful story laws are still known, are sacred, and their powerfulness understood. The amazing thing about the richness of our ancient culture is its strength, what it gives to us, and that we have been able to continue surviving even through hell times. Most of all it keeps us grounded. Being grounded is our strength.

What animals do you dream about?

If I was not writing books, I would probably dream more about animals. The significant dreams I had while writing Praiseworthy were often about becoming hopelessly lost, of not being able to find my way home. Perhaps these dreams were also a part of something else: a scream from the subconscious, of a country calling me to dream about animals instead of fathoming the concerns of writing Praiseworthy.

At one point you talk about the poor quality of hate. Do we hate worse now than before?

Praiseworthy is an attempt to capture the scale of the spirit of our times. In our culture, we are told if we do not care for our country, our country will not care for us.

Freedom and wildness are at the heart of the novel. The novel itself is a spectacle of freedom. In one passage, the authorities decree the elimination of wild animals, but they soon begin to make exceptions. For you, what does it mean to be wild, or to be domesticated?

The novel has a lot of wildness to it. Starting with the scale of it. While writing, I became more certain about the new work for literature, of what will become its job in the future: to develop works of greater scale. We need to better understand the fast-increasing uncertainties confronting all of humanity. I believe it will be literary works of great scale, promoting a stronger literature and a newer type of literature literate world, that will help us to grow a stronger understanding of this moment of moving backwards as warmongers against each other, when we are really in for the fight of our lives, where surely, all life matters.

Cyclones, fires, plagues of invasive species… everything is present in the book. They say that Australia is the laboratory of global climate change. Do you see yourself and your community as laboratory rats?

No. The reality of global climate change is that it is global. There is no safe haven anywhere on the planet from global warming.

Fire in Central Australia. “While many Australians feel the need to care for the environment, the reality is not that way.” Photo: Andre Sawenko

Is it difficult to find other Widespreads in Australia? I mean independent Aborigines capable of promoting good projects for the Aborigines themselves outside the Australian government.

In early September 2024, I was given the honor to present the keynote address for the 40th anniversary of the Carpentaria Land Council. I am a member of the Carpentaria Land Council which includes nine Aboriginal nations, including my traditional Waanyi homelands in the southern highlands of the remote region of the Gulf of Carpentaria, and covers 85,000 square kilometers of land, and over 600 kilometers of coastline. This is part of the speech: “I have always admired the fact that the Carpentaria Land Council gives high priority to exciting its young people. It recognizes that our young people are the heart of our culture and excites its young people to become ready for their future. […] We see this through the magnificent work and achievements of the land council’s world class Ranger Units. Our Rangers learn how to protect the world which they will leave to their children. They are also learning how to be a good living ancestor in the modern world by acquiring both cultural and scientific knowledges and building strong economies right where they live. They are being prepared to look to the future with much hope, to know that they were born for these times, and to know that they are learning how to become equipped to work for the future of both here, and in the wider world. […] This is nothing new. This is old wisdom. Murrandoo Yanner, a Gangalidda leader, and one of the most important wisdom people in the Gulf of Carpentaria, would say building sustainable economic futures for people on our lands is buying back a piece of your sovereignty.”

Widespread is also defined as “an anti-man of the moment”: an “environmentalist”. How are environmentalists regarded in Australia?

While many Australians feel the need to care for the environment, it is not always the case in reality. Australian politicians support the continual use and development of new fossil fuel mines. I believe some politicians still deny that climate change is even happening. Aboriginal people will and do have arguments with environmentalists preferring to see the environment devoid of people, and have not understood that Aboriginal people have been on, and caring for their traditional unceded sovereign lands over tens of thousands of years.

Widespread wants to make money to improve his community. He is presented as an entrepreneur with a solution as unexpected as it is promising. He is an Aboriginal businessman. Is this figure common among Australian writers?

I do not think that the Aboriginal businessman is a common figure among Australian writers, but I may be wrong. There is possibly no other character like Widespread in Australian literature. Yet.

Most of the main characters are men. Why?

Praiseworthy is indebted to an imaginative and creative process more than any expectation, conventions or insistence of what a novel should do, or contain. I decided very early in my writing career not to be bound to other peoples’ expectations about what I should write about, or what either an Australian or Aboriginal authored literary work should be. I did not want to be boxed in, or comply with what is publishable in Australia, or anywhere else. There was no purpose of writing to achieve an acceptable place in the status quo, or to comply with other people’s agendas, nor to what was commonly valued as ‘proper’ literature. I am driven by other challenges. Of course, in Praiseworthy, there is Dance Steel, the Moth-er—a woman, who lives in the world of Lepidoptera. She is a central character. I enjoyed writing about her.

Many years pass between the publication of your books. What is your writing method?

We clearly live in times where we are exposed to multiple experiences. The complexity is important, it is what brings literary worlds to life, and this richness builds the imaginative experience. The writing of Praiseworthy was loosely guided by a collection of notes and treasured objects. The shape of things that live in the heart, the life force of all worlds and of all peoples, the great harvest of sensibility, wisdom old and new, intellect, drive, sheer guts and tenacity. These were some of the ideas that I learnt from over a half century of work in the fight for Aboriginal rights. I have found inspiration in the random gifts from a windfall: a feather from the local birds, or a perfect bird’s nest that had floated down from the highest tree in a night storm, and fallen undamaged into the garden In the decade of summers taken to write this book, I have watched traveling butterflies dance their life through bushlands and over our gardens. Even before the first word hit the page, I probably always knew that this was going to be a huge literary work. A story told in segments, without rush. And why rush? Our world is of millennia, a culture interconnected across the entire continent, a world much fractured by the enormous consequences of colonizing theft of land and resources, and on alert to continuing attacks on one’s sovereignty of land. Our plight connects us to the growing millions of others, the landless and the persecuted throughout the world suffering from wars, colonization, climate change, and being torn away from their traditional homelands. In such a large work, it was important to constantly keep the sense of direction, without distractions, so it didn’t matter whether I sat in my university office, or my study, or in the garden, or in a park, or in the bush, or if I was travelling, or sitting in a café, the focus on the book came too. And the focus remained. I learned to write anywhere, or at any time, while remaining totally oblivious to anything else happening around me.

The writer in the bush. “In the summers of writing this book, I have watched butterflies dancing in the bush and in our gardens.” Photos: Toly Sawenko and Robert Ham/Wikimedia Commons

Through the character Tommyhawk, the dangerous influence of technology on the youngest is very present. How is the avalanche of virtual information affecting Aboriginal children?

A close reading of Tommyhawk will give the reader a strong feeling of how a colonial history of continued misguided government policies create, and adds to inter-generational harm in the Aboriginal world. If you take away a culture’s governance and sense of their own direction for the future, you have to have something of equivalence to offer in return? What we are now seeing is that the children born in the years of the Northern Territory Emergency Intervention implemented by the Federal Government in 2007, are rebelling and being guided by their own desire to destroy the status quo, resulting in incarceration, racism, and inequality. They grew up with seeing their parents and elders being robbed of their authority by this government policy of Intervention. These children do not seem to care anymore as they set themselves on a path of destruction of their own lives, and the lives of their oppressors in small townships, particularly in Northern Australia.

What role does the sea—and water—play in the Aboriginal imagination?

Aboriginal people who live by the sea have a deep spiritual relationship to it, as deeply as they do with land. The country of the sea is fully represented in the oldest laws, sagas and literature. The sea is prevalent in various works of Australian literature written by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. For example, the work of Tim Winton, the late Beverley Farmer, and the Noongar writer, Kim Scott. This continent is surrounded by sea. We have a close relationship with it.

You write that it is difficult to kill a dreamer. Although the facts seem to show the opposite. Why is it difficult?

If we lived in a world without dreamers, those who think big, those who are driven to create a fairer world, it would be a sad world indeed.

Praiseworthy criticizes the storytellers’ inability to imagine.

Sometimes the storytellers will have problems with a vision man like Widespread. They do not like the way he looks. They do not like his vision. They have either stopped thinking, or do not have time to think, or have found their thoughts have not mattered either in their lives, or in the lives of generations of their people.

Would the death of Aboriginal Sovereignty eventually mean something, or nothing at all?

This was one of the major concerns of the book: what these two words mean after two centuries of continual brutal acts of colonization. This concern was explored through the main character whose name is Aboriginal Sovereignty, and his suspected suicide, captured the imagination of Praiseworthy itself. As they searched the sea, they asked this question of themselves: where is Aboriginal Sovereignty?

At the beginning of the book you mention the Irish poet Seamus Heaney (1939-2013). Why is he a reference for you?

When I began to think about how I might write, I studied works of literature across the world. I needed the guidance of a mentor. I already had plenty of mentors through the very best minds in the Aboriginal world. We come from a world of storytellers. We know literature. We know what sagas look like, that stretch across the country in some places. But in the written world, I thought that I needed someone like Seamus Heaney as a mentor, and through his works, words, compassion, and in a colonizing situation with similarities to ours, and along with other important writers of the world with similar backgrounds, it became a comfort to read and understand where these writers were coming from, while learning how to develop my own voice as a writer.

Another name: what do you think of The Songlines, the work in which British author Bruce Chatwin (1940-1989) wrote about Aboriginal spirituality?

Even though I have read widely, I did not read The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin. I came from the Aboriginal movement where our aim was to achieve rights for our people in the here and now. We searched for answers across the world. I continued a similar type of search in literature through the works of authors who had—and wrote from a position of having—a long unbroken connection to their country. I was mostly looking for a way to write this country in a way where history did not begin with a British colonizer arriving here some two hundred years ago. What I wanted was an understanding of how to write all the times of the Aboriginal world. This was what was important to me when beginning my journey as a writer.

Beach in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Aboriginal people living near the sea have a deep spiritual relationship with water. Photo: Andre Sawenko

Gabi Martínez has written about deserts, rivers, seas, mountains, deltas and all kinds of living beings. He spent a year living with shepherds in Spain’s wooded pasturelands, and another on the island of Buda, in the last house before the sea, which will be the first to be engulfed by the waters in the coming years. After these experiences he wrote Un cambio de verdad [A True Change] and Delta. He has written 16 books and his work has been translated into ten languages. He is the driving force behind the Liternatura project, a founding member of the Caravana Negra and Lagarta Fernández Associations; of the Urban and Territorial Ecology Foundation; and co-director of the Animales Invisibles [Invisible Animals] project. In SUMAÚMA he writes for the LiterNatura space.

Report and Text: Gabi Martínez

Editing: Viviane Zandonadi

With the collaboration of: Meritxell Almarza (Spanish)

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Portuguese translation: Paulo Migliacci

English translation: Charlotte Coombe

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum