In late November, as the residents of the city of Altamira were experiencing some of the hottest and driest days in memory, the directors of the Siralta, the trade association of the city’s large rural producers, held a meeting of members. This was not because of the climate emergency, but to celebrate the arrival of soybean farmers to the region, which was given a joyous reception from local ruralists. They’re from Rio Grande do Sul, the Siralta announced, and are looking to lease “at least” 40,000 hectares of land (equivalent to more than one-third of the area covered by the municipality of Belém, the state of Pará’s capital,) to plant the legume. Some of these southerners had seen their land devastated by this year’s record flooding in their home state.

“It’s quite natural,” said a celebratory Maria Augusta da Silva, Siralta’s president, to a reporter for the SBT network’s Altamira affiliate. “The timber comes, the livestock comes, and [then] the crops come.” What she describes as “natural” is the established cycle of Amazon Rainforest devastation. It starts with the theft of trees that fetch a high market value from public land. It continues with the remaining vegetation being cleared. Then comes the fire, destroying toppled trees and everything that lies in its path, readying the area for formation of a cattle pasture. A few animals are put there to graze, “ownership” is declared over the area, and the hope is that some government land reform program will give its blessing to the land-grabber’s theft of public land. Once the documents are in order, the door is open for crops like soybeans.

Maria Augusta da Silva, a ruralist, rejoices ‘farming’s time,’ which should lead to greater deforestation in Altamira. Photo: Screenshot/Siralta Instagram

Altamira, Pará is Brazil’s largest municipality in area. Portugal would easily fit one and half times into its 159,000 square kilometers. To the south, on the border with the state of Mato Grosso, soy crops have already been established. Yet in the city’s more urban region, occupying a small fraction of the municipality and located to the north, along the banks of the Xingu River, it had never come knocking. Altamira is famously home to the Belo Monte Dam, which has been prejudicial to the humans and more-than-humans that lived and are still trying to survive in the Volta Grande region of the Xingu River. And long before this it was known as ground zero for the Trans-Amazonian Highway, a megalomaniacal project undertaken by the country’s business-military dictatorship (1964-1985).

The Trans-Amazonian Highway was designed to bring Brazil’s northeasterners, punished by drought, as well as smallholders from the south who were demanding agrarian reform, to a region that was nothing more than a “demographic void” in the limited view of the military, even though Indigenous peoples had been living there for centuries. “The highway was an escape valve for the social pressure in the south,” explains social scientist Maurício Torres, a professor and researcher at the Federal University of Pará who studies territorial conflicts in the region. People came en masse from Rio Grande do Sul to the Trans-Amazonian Highway – but they weren’t the southerners being lauded at the Siralta meeting. “Agribusiness is who’s coming now, not the poor, miserable peasantry of the 1970s. They were expropriated; the people coming now are the expropriators.”

‘There’s no drought here’

These new southerners from Rio Grande do Sul introduced some big plans to Siralta’s membership. In Vitória do Xingu, at the edge of the municipality of Altamira, a company is building four silos with the capacity to hold 26,400 metric tons of soybeans. Their construction is being managed by Dura Mais Armazenagem de Soja, whose paperwork, declaring R$ 8 million in company capital, was filed in May by a group of southern executives. Its arrival in the region was based “on detailed market analyses and studies on the sustainable growth potential of agricultural production in the Xingu Valley,” Alexsandro Konzen, one of its administrators, told SUMAÚMA. In responses sent by e-mail, he refused to discuss the project’s costs and the people bankrolling it. “This is strategic and confidential information and, therefore, it cannot be publicly disclosed.”

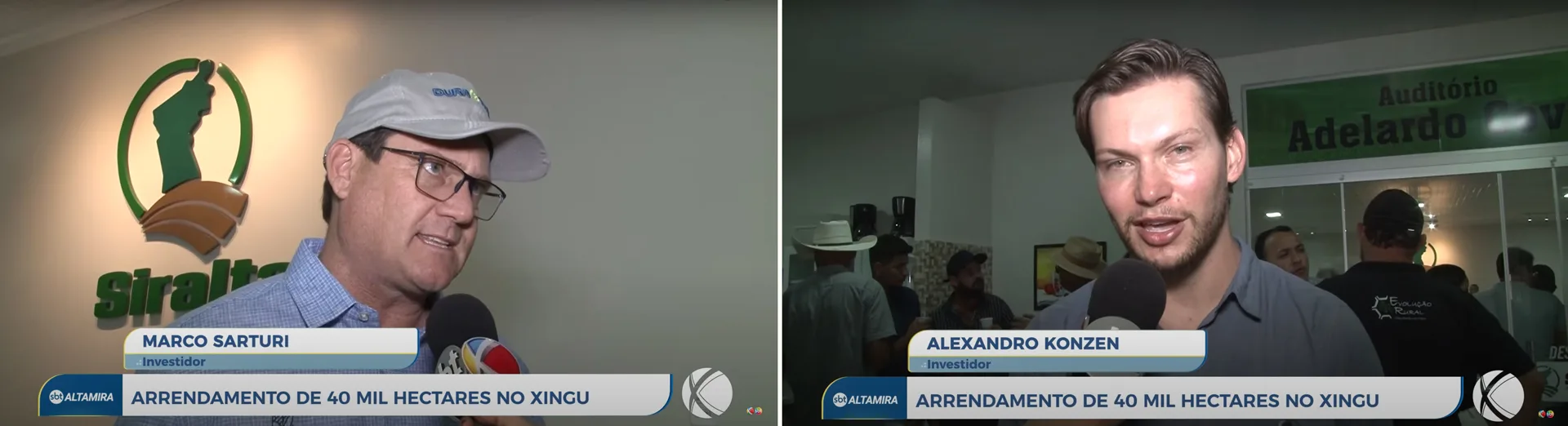

The same confidentiality is also extended to those leasing land. Marco Aurélio Sarturi introduced himself as their “representative.” Sarturi told SBT’s Altamira station that he made it clear the soybeans that will be planted there are for export, through ports like the one in Santarém, another city in Pará. “You probably saw what happened in Rio Grande do Sul,” he said, referring to the devastating flooding in the first half of 2024. “In addition to this, [there were] three years of drought. So, producers are looking to migrate to more favorable regions like here, capable of producing two annual crops without the risk of drought.”

The southerners: Marco Aurélio Sarturi, representing soy farmers, and Alexsandro Konzen, a silo builder. Photos: Screenshots/SBT Altamira

The inability to see the extensive and predatory agriculture practiced in the south as one of the causes of the region’s climate catastrophes did not go unnoticed. According to MapBiomas, in 2023 only 43% of the original plant cover remained in the Pampas, Rio Grande do Sul’s iconic biome. Moreover, since measurements began in 1985, there has never been a period as dry as the first four months of last year in the Brazilian Pampa. On the other hand, in 2023 it rained so much in Rio Grande do Sul’s Atlantic Forest – predominant in the state’s northeast – that water surface area exceeded the historic average by 19%. Science has already drawn a line between deforestation in the Amazon (which affects the movement of humidity in the air along what is usually referred to as “flying rivers”) and irregular rainfall in Brazil’s south and southeast. “The model [of land exploration and use in Rio Grande do Sul] generated catastrophes, but they don’t feel like this means it didn’t work,” Maurício Torres says with astonishment.

Marco Sarturi told SUMAÚMA that he is not a soybean farmer. He sells seeds and agricultural supplies in Santiago, a municipality in Rio Grande do Sul known as “the land of poets” – Caio Fernando Abreu, among others, was born there. A few years ago, he opened a branch of his business in Sorriso, Brazil’s soybean capital, in the state of Mato Grosso. “It’s a group of farmers who’ve already had crops in Rio Grande do Sul and in Mato Grosso for many years,” Sarturi explains about his customers. “I’ve worked in ag for 32 years. I have an electric mobility company and another for biological products. I went to the north [of Brazil] to help some producers who are suffering from climate problems and the only thing they know how to do is produce food,” he said. The merchant made a point of saying that he and his customers care about the environment. “I want my grandkids to continue to grow up healthy.”

A predatory model that isn’t sustainable: soybean monocrops flooded by devastating floods in Rio Grande do Sul. Photo: Emater / Rio Grande do Sul

‘The crop of death’

“It’s farming’s time,” Siralta’s Maria Augusta da Silva told the local TV station. Trying to get ahead of any side effects, she quickly added, “Of course without any more deforestation.” Degraded pastures abound in the municipality, ready to be converted into soybean fields, she justified. It’s true. But not entirely true.

According to MapBiomas, 1.1 million hectares of Altamira served as pastureland in 2023. A year earlier, according to the Amazon Foundation to Support Studies and Research, a Pará state government agency, Altamira was home to 1 million head of cattle. That is a lot of land for little cattle, an example of low-productivity livestock farming, as well as of how these areas are no longer useful as pastures. Even so, this is close to the state’s average, as the state agency registered in its most recent agricultural bulletin, issued in late 2023: “The productivity rate of the cattle herd in Pará has risen slightly over 37 years, going from 0.9 to 1.1 head per hectare from 1986 to 2022.” One hectare is more or less the size of a football pitch. It doesn’t, therefore, seem to be a problem for some of these areas that go unused by cattle to be converted into cropland.

Yet soy’s arrival has created another problem: appreciating land values, leading small landowners to sell. “And then they’ll buy [different land] far away, that is very hard to reopen again,” says Everaldo Amorim, president of the Union of Rural Family Farm Workers of Altamira. He uses “reopen” to refer to areas where there is generally still forest and the local roads and secondary roads – also known as side roads – run perpendicular to highways like the Trans-Amazonian and give deforestation in the region a fishbone appearance when seen from above, in satellite images.

It is a vicious cycle. With one aggravating factor: many areas bordering these side roads are Indigenous Territories or conservation units, says Maurício Torres, a professor at the Federal University of Pará. “Livestock farming will advance over the settlers’ area, who in turn leave to open new frontiers. So, indirectly, soybeans should create deforestation of Indigenous Territories and conservation units.” Amorim backs this up. “[The pressure] isn’t just on cleared land, but on the federal government’s own reserve areas.” The alternative to destroying protected areas is abandoning the field and trying your luck on Altamira’s urban outskirts – already swollen, violent and dominated by organized crime.

All of this has already happened not far from there, in Santarém, along the banks of another major tributary of the Amazon, the Tapajós River, where multinational grain exporter Cargill built a massive private port, as reported by SUMAÚMA. “The first sign of Cargill facilities came in 1998. It was a very abrupt arrival, we didn’t even know what this soy monocrop was,” says Maria Ivete Bastos dos Santos, a local leader of traditional community workers who has witnessed the barbarism that comes hitched to the oilseed.

Bulk carrier at the Cargill port in Santarém: soy has devastated the region’s traditional way of life. Photo: Michael Dantas/SUMAÚMA

“Soybeans caused the biggest damage to our lives. It silted the streams, deforested the chestnut trees, the pequi trees,” she recalls in a statement that casts a dark shadow on Altamira’s future. “We’ve experienced plenty of sad stories, seeing the loss of family farming, agrochemicals invading people’s lives; lots of women, mostly, dying of cancer. Because the poison is for everyone, just like the smoke we’re breathing in now.” When Ivete spoke with SUMAÚMA, Santarém had been plunged into a cloud caused by forest fires and had the planet’s worst air.

Everaldo Amorim predicts what’s coming. “Our concern is the water here,” he says, referring to the rivers and streams already affected by the Belo Monte Dam. “We know how many types of agrochemicals these guys use, we know the water will also become contaminated. Unfortunately, the market is very fierce, very greedy.”

In Altamira, two days after the Siralta meeting, university professor Rodolfo Salm made a video discussing how he expects the imminent arrival of soybeans and clouds of smoke from fires. “It’s November 29, and no sign of rain. We’re suffering from worse and worse droughts, but the precipitation is still plenty suitable for soybeans. With the migration of soybean producers, deforestation should explode, and the drought will become more and more intense. We’re going to import drought to the heart of the Amazon and export poverty to the rest of the country,” said Salm, who holds a PhD in Environmental Sciences from the University of East Anglia and is a professor of Ecology in the School of Biology at the Federal University of Pará’s Altamira campus. The first somewhat heavier rain would only fall days later, on December 5. But it was an isolated shower. “I’ve been here since 2008 and I’ve never seen a year as dry as this one,” he told SUMAÚMA. On December 10, when this story went to press, the drought remained.

From Santarém, Ivete went ahead and summed things up. “We weren’t the ones to promote this very chaotic climate crisis, rather it was all these agribusiness people who came, got set up, and destroyed nearly our entire life, as well as the forest, rivers and everything that exists. For me, soybeans are the crop of death.”

A waterfront on the Tapajós River in Santarém under a blanket of smoke so thick it makes Cargill’s facilities hazy: the worst air in the world. Photo: João Laet/SUMAÚMA

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum