It has not been widely publicized that the boreal forest is the largest terrestrial ecosystem on the planet and occupies almost one third of the total forest area. And Canada is not often thought of as an oil-producing power, even though it is the world’s fourth largest producer. But it is critical to understanding why 2016, in the Canadian province of Alberta, ignited the most destructive wildfire on record in recent times, burning for fifteen months and elevating the idea of fire to a new category. In fact, for the first time in history, a fire was given the name of a living thing: The Beast.

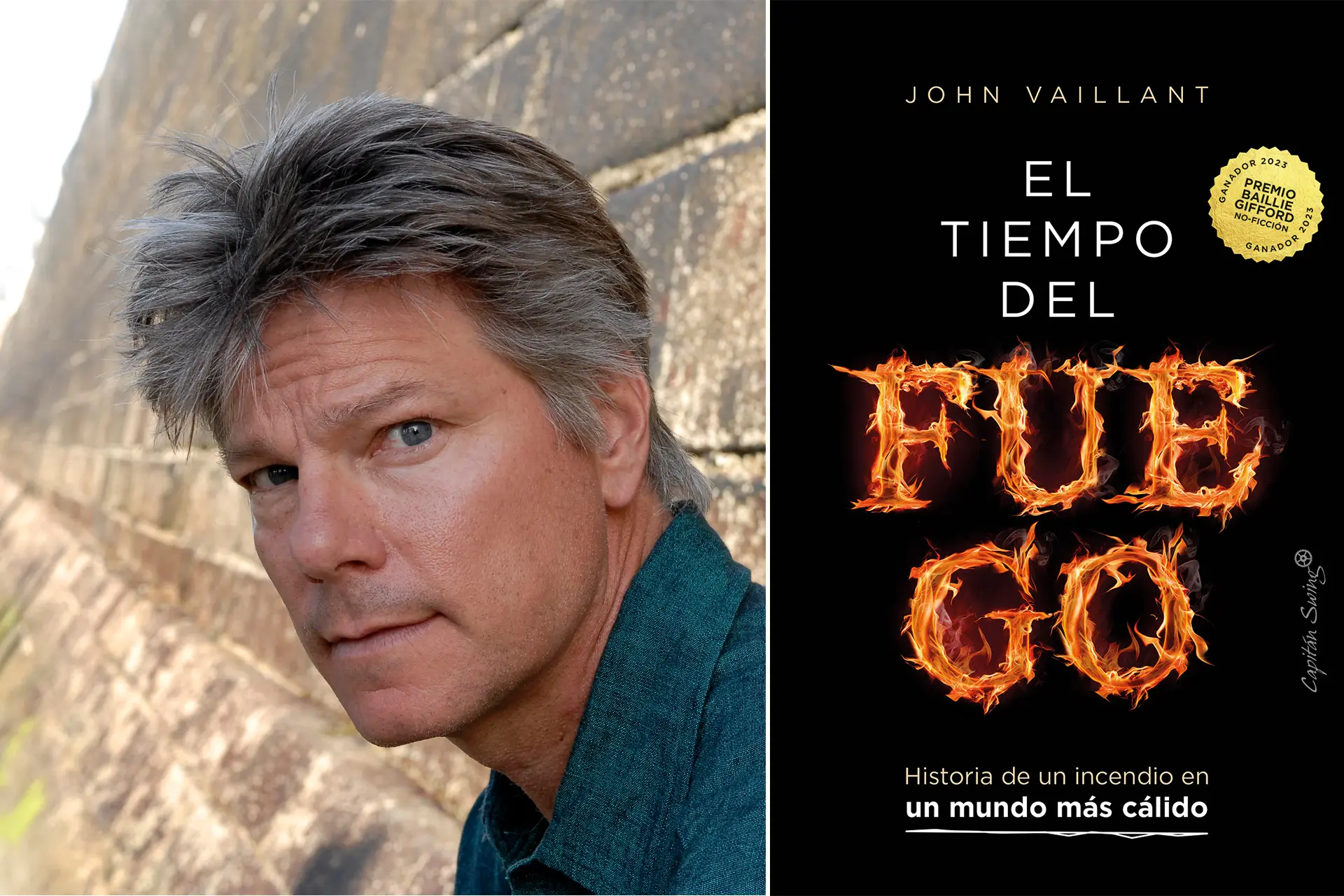

John Vaillant (Cambridge, 1962) has written an impressive book about him: Fire Weather (Hachette, 2023). In The Tiger (Penguin Random House, 2011) he accessed, in an unusual way, the inner world of a big cat. Now he speaks from within the belly of a fire. Specifically, he focuses on how and why Fort McMurray, Canada’s oil capital, is razed to the ground: a town built with ultra-flammable materials manufactured by that same industry, ignoring the lessons that were supposed to have been learned after the great fires of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The American-Canadian writer x-rays the new fire. Its chemical composition allows him to describe its surprising behavior. “Fire,” he says, “is neither an element nor a reaction, it is a hunter.” Flaming needles, flying embers and glowing balls add to the exploding engines and tanks and the volatile structures and roofs made with petroleum and the wheels measuring up to 4 meters, used by the gigantic trucks that go to the bitumen mines, producing staggering temperatures creating unprecedented tornadoes of fire that make the flames spread unexpectedly and double back on themselves.

What is striking is that this creature is a new product of excessive human greed. “Fire is, along with the brain, opposable thumbs and speech, our superpower,” says Vaillant.

John Vaillant is the author of Fire Weather, a book which explores the causes and effects of the phenomenon he calls ‘21st century fire’

LITERNATURA – When did you decide to write a book about fire, and why?

John Vaillant – When the Canadian petro-city of Fort McMurray was overrun by fire on an unseasonably hot May afternoon in 2016, it was clear from the fire’s intensity, and its subsequent behavior, that we were turning a corner in our relationship to fire – not just regionally, but climatically and planetarily. Fire Weather is an attempt to explore the causes and effects of this phenomenon, which I term ‘21st Century Fire’. The book took me 7 years to write and publish.

After writing about a tree and big cats, what was the experience of writing about a chemical reaction like?

All of these topics challenge me as a human being – to make empathic leaps across species, and now, chemistry! It’s exciting and, I believe, necessary in these times human exceptionalism is enabling ‘Othering’ and so, the destruction of the creatures and systems we depend on.

The magnitude and tenacity of fires in the boreal forest is largely unknown on a global scale. Why do you think that is?

Remoteness and provincial interests. The Russian taiga, another boreal forest (where the action of The Tiger is set), hosts colossal fires, too.

How do you relate to fire, before and after the book? Has the fact that you have come to be so close to it affected you in any particular way?

-I loved the challenge of understanding fire, which was really a mystery to me before writing this book. At one point, a couple of years into the book, when I was having a really hard time and a poet friend, Elee Kraljii Gardiner, suggested I interview Fire. I did. It forced me to observe and imagine its essential behavior and appetites from a chemical and physical point of view, without emotion. It was very helpful. After that, I think I made a breakthrough, being able to identify all the ways it resembles other living creatures, including us. I’ve always felt a comfort and kinship with fire because I grew up in houses where we used it for heat. So, I have been tending and ‘feeding’ fires for most of my life. Cutting and splitting firewood is one of my favorite things to do.

You must have read a lot about fire and fires. What books have you used for reference? How has fire been dealt with in literature so far? What did you want to contribute to fire literature?

The American writer Stephen J. Pyne is the greatest living chronicler of fire culture and behavior, worldwide. I mostly read about the science of oxidation and fire behavior – very dry stuff, and then I animated it with my own observations and those of the people I interviewed. I wanted to connect some dots between our biology and chemistry, and that of fire, and then connect that to our appetites and ambitions, showing how liquid fuels have amplified our ability to consume and create far beyond earth’s regenerative capacity.

You say that the oil entrepreneur lineage is heavily represented by evangelical Christians. After the Fort McMurray fire, what did the evangelicals who lived in the area think about climate change?

I don’t know. They don’t discuss it openly. They are deeply invested in a petroleum-centered status quo. Most people’s beliefs are tailored to their immediate self-interest, and to conforming to the accepted beliefs of their community.

Out go pine trees and people, and in come open-pit mines. “The evangelicals who lived in the affected area are deeply invested in a petroleum-centered status quo.” Photo: Ed JONES/AFP

You emphasize the inability of the human species to imagine anything outside their personal experience. This is why we are so slow to react to a new threatening situation. The Lucretius Problem. But there are more and more people with extreme personal experiences linked to climate, and the pandemic had a global impact. We are no longer talking about abstractions. However, the 009 fire was publicized in the media as being unrelated to climate change. And 62% of Alberta’s United Conservative Party representatives voted in 2021 not to include climate terminology in their arguments. But almost nobody protests, nobody demonstrates, apart from the environmentalists. Why do you think this is happening?

Because of what I said before.

The status quo.

The status quo.

You write that, as far as the evacuation of Fort McMurray was concerned, “deep allegiance to the internal combustion engine posed a major problem.” It is amazing to see people crying to save their motorbike. One of your objectives as an author is to highlight the contradiction in which we live… and the dependence. Are we addicted to fire?

I think so – kind of the way we are ‘addicted’ to oxygen: Fire made us who we are today. Life without its amplifying energy is unimaginable – and for most of us, would be unliveable.

Fire Weather is clearly critical of how things have been done in the region. How has the book been received in the areas devastated by the fire? Have you done book events there?

Heh. It’s been quiet in Alberta. I have done several events there to full houses where you could hear a pin drop: people are very interested in this subject, but it’s also very uncomfortable because it highlights the unsustainable contradictions in which many Albertans —and many of us— live. What’s interesting to me is not the lack of praise, but the lack of criticism. I tried to write a book that Albertans would feel welcome in. Many outsiders bash them and the petroleum industry. I tried to humanize both.

Cars, private storage, the material with which houses have been built… all contribute to accelerating the combustion of the city. Has the reconstruction been carried out with other materials, following other criteria?

Nope. Status quo, all the way. They are in pretty much total denial..

Has the tragic example of Fort McMurray led to preventive actions in other cities, in the forests? Or is construction still being carried out with highly flammable materials?

Many other communities are looking closely at their evacuation plans, but few to none are building differently. Housing is such a hot-button issue, and there’s so much money to be made there that progressive change will be slow and difficult.

In the book you provide a wonderful list of people who have studied and warned about the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the 19th century. Despite the scientific reports warning of the fatal effects of global warming, in 1984 “bankers, economists, CEOs, evangelical pastors and complicit conservative media” chose to ignore the scientific evidence and caused the emission of even more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. “Yes, we knew it,” says Shell executive Ben van Beurden. How would you describe this confession?

I would describe it as brazen. But it’s not new or particular to the oil industry – the arms industry, the auto industry, the chemical industry, their financiers, and enabling political leaders all kill people, directly, in their thousands, and they know it, too.

Do you think that justice is being fair to people who are consciously causing levels of destruction and death as great as those reflected in your book?

No, in the sense that the lack of accountability of those responsible (including investors) rewards their behavior.

Wildfires in California are out of control. “The president-elect and his supporters in the media will use this tragedy as a weapon against California’s liberal government.” Photo: Patrick T. Fallon/AFP

Insurers and some court rulings have prompted a change in corporate investments, but the outcomes of recent summits such as COP29 in Bakú, or the fact that in 2024 the historical record for oil consumption has been broken in the United States, do not seem to favor a real change in trend. What point do you think the planet is at today?

I think it’s in big trouble. We are going off a cliff right now. Terrific strides are being made in renewable energy, but most of it is -additional- energy rather than -replacement- energy. I think that ratio will change, but it’s not happening fast enough to reverse the damage done. Thanks to the right-leaning, petroleum-industry-financed governments in North America and elsewhere, transition away from rampant petroleum and coal consumption is going to get slower and more difficult. The insurance industry has leverage to move the needle by withdrawing coverage (which it already is), and by openly attributing loss of coverage to the effects of climate change, but I don’t see this happening. The financial markets, and their dependents, are hostages to profit-making, until climate change impacts the wealth-building process, these powerful entities and their oligarch masters will delay action. It is criminal and should be treated as such. The catastrophic damage to LA county is a perfect example, but only one among many.

Do you think that fires in North America —the United States and Canada— have more of an impact than those in other parts of the world, in terms of changing the political and business dynamics in these countries and the rest of the world?

I think it’s possible, but unlikely because the incoming president and his enabling media will weaponize this tragedy against California’s liberal government, instead of using it as a way to show that no city —no matter how rich or famous— is safe from the effects of climate change.

Lately, we’ve been hearing more and more that in order to raise awareness in society, we should not scare people with apocalyptic environmental stories but should speak positively instead. What do you think?

I agree: I don’t think fear works that well; fear leads to despair and/or tuning out. The antidote to fear and despair is agency: in order to remain engaged and hopeful, we need to feel like we have some control over our fate. We are in a cynical and polarized time in which bad actors are manipulating attitudes and emotions with great effectiveness in order to maintain a planet-destroying status quo. The rich want to stay rich, but what they —and most of us— fail to understand is: It doesn’t matter what business you’re in, Nature owns 51% of it. Burning fossil fuels has put us in debt to Nature, and now she is ‘collecting’ on that debt with every weather disaster. She is communicating with us through the weather, through extinctions and plagues and infestations, and it is suicidal to ignore her.

Anyway, you say: “We are a supervolcano” capable of transforming the atmosphere. But there are no volcanoes in perpetual eruption. Is that the quality of the supervolcano: not ending until it has destroyed everything?

Supervolcanoes and fossil-fueled human civilization are both organic processes on the big-picture, planetary scale. They stop ‘erupting’ when the energy driving them is exhausted. There many different scenarios that could slow or stop our current explosion, and we are witnessing many of them right now in the form of weather, disease, and environmental and social breakdown.

In the book, there is a lot of scientific and specialized terminology. And new concepts, as cutting-edge as the fires themselves. New ideas and vocabulary appear. You also mix literary genres. Is writing about nature, today, a form of avant-garde?

Oh! I love the idea, but I don’t think it’s for me to say. One of my objectives and responsibilities as a writer/communicator – is to keep the language fresh and alive, and to find ways to get difficult or challenging information past people’s emotional, intellectual and ideological defenses. The beauty of art and science —and of being a human being—is that they are syncretic acts, we are always borrowing, mixing and matching. Creation, evolution, is a joyful process to be part of.

The fires in Canada forced more than 80,000 people to evacuate. “Nature is communicating with us through the weather, through extinctions and plagues and infestations, and it is suicidal to ignore her.” Foto: SCOTT OLSON/Getty Images via AFP

Gabi Martínez has written about deserts, rivers, seas, mountains, deltas and all kinds of living beings. He spent a year living with shepherds in Spain’s wooded pasturelands, and another on the island of Buda, in the last house before the sea, which will be the first to be engulfed by the waters in the coming years. After these experiences he wrote Un cambio de verdad [A True Change] and Delta. He has written 16 books and his work has been translated into ten languages. He is the driving force behind the Liternatura project, a founding member of the Caravana Negra and Lagarta Fernández Associations; of the Urban and Territorial Ecology Foundation; and co-director of the Animales Invisibles [Invisible Animals] project. In SUMAÚMA he writes for the LiterNatura space.

Report and Text: Gabi Martínez

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

With the collaboration of: Meritxell Almarza (Spanish)

Photo editor: Soll

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Portuguese translation: Monique D’Orazio

English translation: Charlotte Coombe

Editorial workflow: Natália Chagas

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum