The meeting couldn’t be held in the Amazon, yet Araquém Alcântara found a tucked-away corner of nature in São Paulo. At Burle Marx Park, in the state capital’s South Zone, native species of Atlantic Forest and at least 164 types of animal survive. Wearing shorts, a hat, a vest, a camouflage shirt, and his trusty Leica around his neck, the photographer who has taken shots of the Brazilian Amazon for decades is caught by surprise, at the start of his chat with SUMAÚMA, while making an offering to Oshosi, his forehead against the tree trunk.

The scene could be a portrait of Araquém and his work. In Candomblé, a religion his father introduced to him, Oshosi is the orisha (spirit) who extols Nature. “I only found out I was a child of Oshosi, and that I had everything to do with the forest, a long time after I was already in the forest. Because my father practiced Candomblé, I began to care more about this. Whenever I go into the forest, I say a little prayer to Oshosi and to Obatalá.”

Squirrel monkeys, snapped by Araquém in 2016, in Acre. The photographer, who carries influences from Candomblé, makes an ‘offering to Oshasi.’ Photos: Araquém Alcântara and Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

The mandatory ritual for those who respect the greatness of the Forest and the more-than-human lives is part of a long career that has garnered him countless awards, 61 published books, and national and international recognition as one of the most important Nature photographers in Brazil. Araquém, now 73, is a storyteller. A frenetic and superlative one – “I exaggerate and lie,” says the man who nearly died five times: a canoe out of control, a near plane crash, a kidnapping, a farmer’s shotgun in his face, and a crossing on a “precipice” atop the Pico da Neblina. Yet he has never feared any of the animals whose souls he has captured. He feels respect. Interaction. The photographer, who sees himself as “completely unbalanced,” says he has a mystic and centered connection when he goes into the woods. The Forest. The Amazon. The prayer before embarking on any journey through Brazil’s biomes is wrapped in a message of respect for the more-than-humans: “I’m here, I’m available: so appear.”

He says he can see God in his contact with the animals. “I see Tao. I see the soul. And I take a picture. In 2006, Araquém’s book Amazônia took second place in the Photography category at the Jabuti Award. Years later, in 2020, he published Brasileiros, with images of humans who protect and live in symbiosis with the Forest, and which was also a Jabuti finalist in the Essays/Arts category. The book Araquém Alcântara: Fotografias rendered the photographer his first “Benny,” at the Premier Print Awards, in Chicago, in 2012.

His father’s religious teachings were added to four years at a Carmelite Catholic school, in Itu, São Paulo state. Spirituality and intuition are, therefore, strong features of his personality and the photographer says he has developed the ability to meditate and respect the divine. “I prefer to see.”

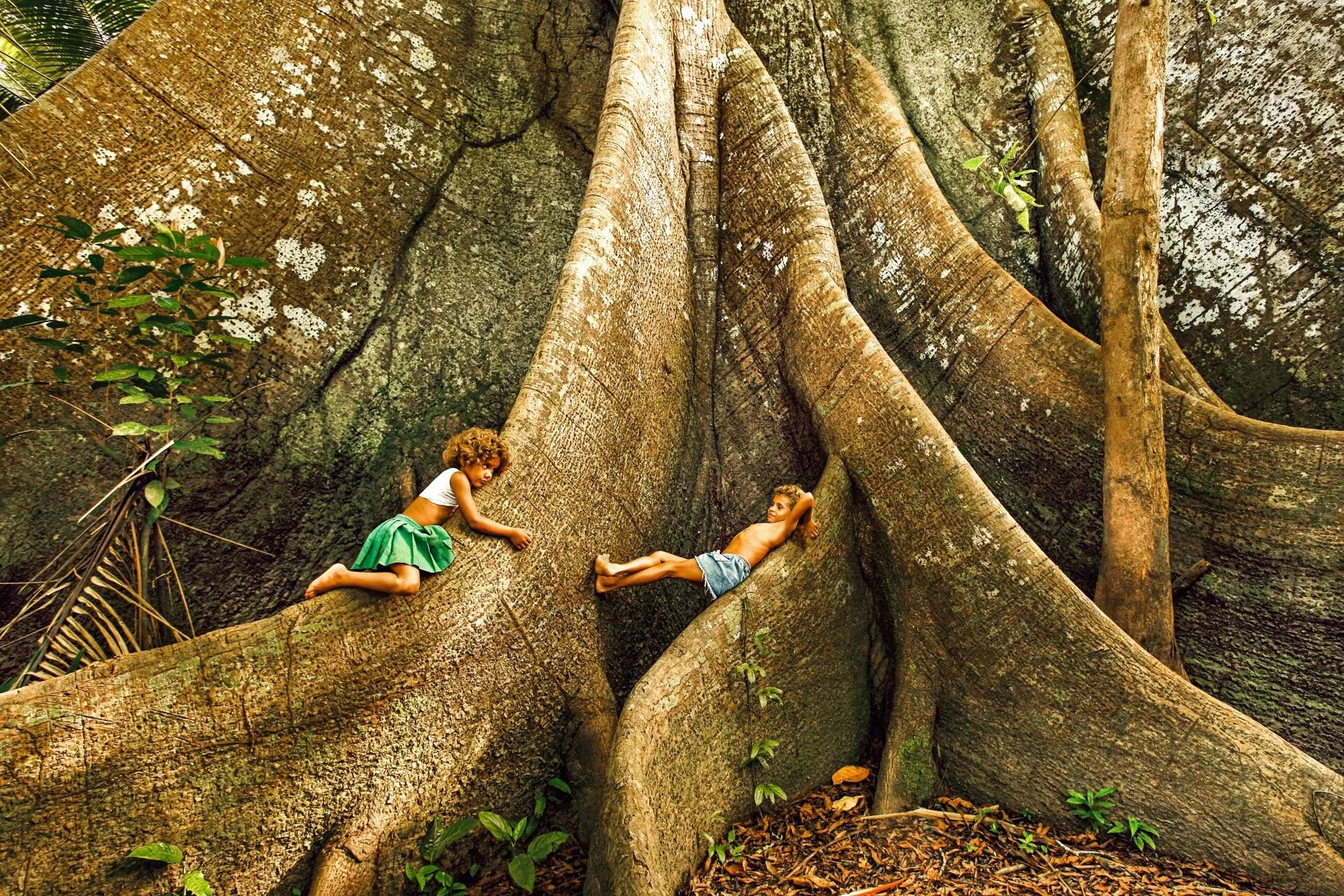

Kids and Sumauma, Barcelos, 2018. Photo: Araquém Alcântara

Being idle is not in Araquém’s soul. Restless, he is already preparing a “seminal” book that he intends to launch by 2030 to celebrate a 60-year career and over half a century of photographic coverage of the Amazon. Inexplicably, he already knows how many pages it will have: 432. “I’ve been thinking about this thing, and one of the names for my next book could be ‘Amazônia em Transe’” (Amazonia in a Trance).

“I am thankful every day to have found the Forest and photography. But don’t tell me that I’m a successful guy.” In the face of so much restlessness, his own name – Araquém comes from an Indigenous word meaning “bird that sleeps” – is a contradiction. “I don’t like to sleep, agitation is my thing. You have to live. This thirst for life accompanies me, this is my vital energy.” His father was inspired by José de Alencar’s novel Iracema, naming him after the protagonist’s father Araquém.

The first jaguar

He took his first Nature photo in 1979, “with a Pentax screwmount, 300mm telephoto lens,” on Xiborena Island, between the Negro and Solimões Rivers, where he found a jaguar playing in a stream. “The first picture of the jaguar, or my first actual Nature photo in the Amazon, was this one, in 1979. I was enchanted there, the certainty that I would shoot a lot of jaguars, the certainty that I would be a photographer. There it was confirmed, consecrated.”

First jaguar, Guedes Stream, Manacapuru (Amazonas), 1979. oto: Araquém Alcântara

The trip to Manaus was in no way related to Nature photography. Araquém had been hired to photograph a corporate event, the opening of a Goodyear tire store in the state capital of Amazonas. But he overheard a waiter talking in a bar about a jaguar that appeared daily at “Guedes Stream.” It was enough for him to radically change his plans.

“I went with the guy, we took forever to get to the island… Because there you never get anywhere. In the Amazon, you’re always at the brink of the unattainable, of total utopia. The distances are impressive,” he recalls. The jaguar didn’t appear on the first day. Persistence, resilience, and patience were necessary. And finally, after hours of waiting and searching, he saw it: “Suddenly, I see a giant head in the stream. It takes a branch, picks it up and bites. Joy.”

When a picture happens as hoped, Araquém says he feels “a rare and indefinite pleasure.” “I call it a photanga, which is a spectacular photo. It takes a long time to happen, but you know right away, it’s impressive.” In a profound connection with nature, the photographer adds, it is possible to understand that Nature is laid out like a gift. “Suddenly I hear a sound, I look, and it’s the ballet of a leaf falling, better than Baryshnikov [Latvian ballet dancer Mikhail Nikolaévich Baryshnikov]. I’m certain it’s being done for me, it’s for you, all of this beauty, and then you commune.”

Araquém walks through the woods and along the trails in Burle Marx Park with impressive energy. He identifies birdsong, explains his fascination with trees and the evening light – the “leaden sky, that slightly gold thing, that fantastic blue” – and he talks about how he always follows his intuition. He sees a beam of light slicing through the tree branches and points: “Look how beautiful that is, perfect light for a photographer; now imagine a harpy eagle, two toucans, and me with my 600[mm telephoto lens] here. I mess with this light. You keep learning to understand the light over time.”

Biguatinga, Juréia/Itatins Ecological Station, Peruíbe/Iguape (São Paulo), 1979. Photo: Araquém Alcântara

Wonder in the perfect society

Araquém was born in Florianópolis, but he started working as a journalist and photographer in Santos, São Paulo. He chose the city where he started his career to host an exhibition on “50 Years of Photography,” running through July 21 at Pinacoteca Benedicto Calixto. His father, a ship steward, was born in Araranguá, Santa Catarina, and his mother, a harvest worker in the mountainous region of Vacaria (Rio Grande do Sul), met in Florianópolis. His strong relationship with his father, Manoel Alcântara Pereira, intersects profoundly with Araquém’s career path.

“I remember going on a boat with him – look what he did for me – when I was 4 or 5. We took a long trip, two months, to the shores of João Pessoa, in Paraíba. Those enormous fish jumping, that they fished off the back. He took me there to the bow, and that ball of sun… Look at the wonder emerging in me, that ball of sun and those birds flying into it. Later I came to see this in the Pantanal, but it started there with my father, and I’m sure, this wonder for what is great, for what is sacred.”

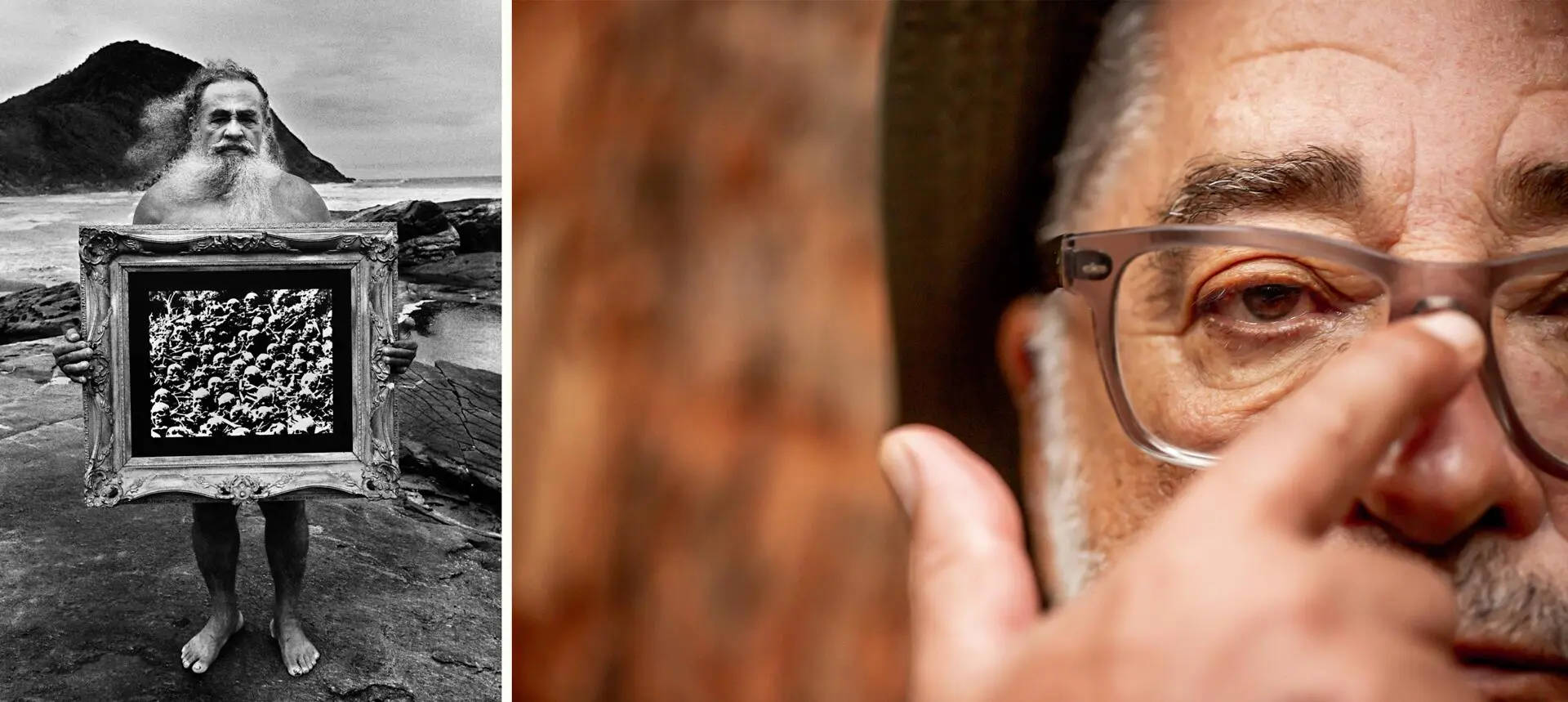

A portrait of his father, taken in 1980, in a protest against the installation of nuclear plants in Iguape, São Paulo, is another milestone in Araquém’s career. “He was up for walking some 33 kilometers with me, on a pilgrimage against the plants’ installation. He was carrying the picture [with the unburied skeletons of Hiroshima], I would trade off with him, he looked like he was fulfilling his vows. All the caiçara children ran away, because he had that beard and that hair, and I was a ‘big hippy.’ How I wish I had a picture with him from that day…” Before taking his picture, Araquém asked his father to get naked and hold the picture. “I only took three or four snaps. That image represents my career. I think it’s one of the most significant, more than the animals. We hugged each other and my dad said: ‘They’re not going to build anything here.’”

A picture of his father, Manoel Alcântara, taken in 1980, is an image that Araquém (at right) says represents his career. Photos: Araquém Alcântara and Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

One of the hallmarks of the “obsessive, passionate, tireless journey of interpreting Brazil” was the book TerraBrasil (1997), the country’s best selling photography publication. “I had 15 years of documentation, of the Amazon, Pampa, Cerrado, Caatinga… My contribution to Brazilian photography is to bring together the ecosystems in the book and their people, even if in a fragmented, superficial way, because Brazil, as Tom [Jobim] says, is for professionals. This country has insane biodiversity,” he says.

The experience made him believe that “the Forest really is a perfect society,” Araquém says. “You feel present when you are the Earth. I’m really crazy. Sometimes, I’m walking in the woods and I feel I’m walking with the Earth. He has stories of each meeting with the animals he has photographed, jaguars, wolves, anteaters, snakes, racoons, countless birds. The photographer says he feels the magic when the animal he wants to photograph accepts his presence.

Marsh deer in wildfire, Poconé, 2021. Photo: Araquém Alcântara

Because he knows how to read the Forest’s soul, Araquém is disgusted by the instant destruction of something that took centuries to build. In 2020, he spent weeks in the Pantanal taking pictures of the biome being destroyed by fires. He was particularly concerned with having a record of the animals’ despair while fleeing, attempting to escape the scorching flames. At the time, he said he looked into “the face of horror” and did not tire of denouncing humans’ “brutality and ignorance.” “We don’t deserve to be guests here. We should treat the tree as a sacred being, period. And it’s there in the Constitution. The name of this country is Brazil Wood.”

Today, Araquém Alcântara recognizes two landscapes: “the poetic and the political.” As a child of Oshosi, a fighter, he remains indignant with what he sees and documents in the Amazon, especially after watching the Forest’s gradual destruction over his 50-year career. He stubbornly believes this scenario will be reverted. He says he places his hope in future generations and believes in the possibility of a happier and healthier life, “despite the extreme events and these cataclysms that will arrive.” “The utopia is what keeps me a photographer. Because how, in so little time, can so much be destroyed? If it weren’t this utopia, I wouldn’t keep taking pictures. But I’ll snap pictures until I die, if I can.”

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum