Each month Rosilene Sousa dos Santos, part of the traditional forest community of ribeirinhos and a member of the Goianinho community in the Amazon, in northern Brazil, collects water samples from the Volta Grande (the “Big Bend”) region of the Xingu River, along the stretch where the river’s flow was sequestered the most to power the Belo Monte Dam’s hydroelectric turbines. She does this to check its quality. Rosilene is part of the Independent Environmental Territory Monitoring of the Volta Grande do Xingu (or the Mati-VGX) group, a project to independently assess the plant’s impacts, whose members include Indigenous peoples and other ribeirinhos. From late August to early September, Rosi – as her colleagues know her – was in Mïratu Village, in the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, in the state of Pará, where she learned the technical name for what she does: limnology, the study of inland waters. She made this discovery thanks to a meeting held in this Indigenous Territory belonging to the Yudjá/Juruna peoples between scientists from major research institutions in Brazil and the top experts on the region’s ecosystems, namely the Amazon Rainforest’s Indigenous peoples and ribeirinhos. In a rare alliance, around forty people spent eight days exchanging knowledge.

There in Indigenous territory, wisdom of sundry origins was melded together. On the one side was the scientific research being done at some of the country’s most prestigious universities; on the other, a deep understanding of the earth, the water, the rocks, and the cycles of life, passed from one generation to the next. The meeting in Mïratu Village marked the first field stage of a project called “Sharing the water and resilience of a unique socio-ecological system in Volta Grande do Xingu,” which was covered exclusively by SUMAÚMA. While they travelled the river, local Mati-VGX researchers and teachers and students from the graduate studies programs at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), the National Institute of Amazon Research (Inpa), and the University of São Paulo (USP) identified new problems in the current that has been forced on the river following the hydroelectric plant’s construction. Will this be the last generation of Xingu children to run after yellow-spotted Amazon river turtles (a type of turtle found in the Amazon, whose capture is an everyday and typical activity in the region that children learn from a young age)? The last generation to see the water-drenched igapó forests? The last generation to fish in the river?

Researchers join ribeirinhos and Indigenous people on an expedition that traveled across the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, home to the Yudjá/Juruna people, in the Médio Xingu region, from August to September of this year

The group is starting a project that will last three years, with financing from Amazônia +10, an initiative of the National Council of State Research Support Foundations (Confap). The project is also working with Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), one of Brazil’s biggest environmental advocacy organizations. With this funding, the collaboration between academics and Indigenous and ribeirinho researchers, now into its second decade, has become an official research project.

University teachers and students split into teams with specific jobs, such as collecting specimens and data according to the project’s research areas: water availability and water quality; environmental heterogeneity, ecological processes, and ecosystem resilience; and geodiversity, observation of birds, fishing and visit plan formation; and community-based tourism. At the end of each day of work, ribeirinhos, Indigenous researchers, and academics gather around a table to discuss their findings. Together, they examine turtles, fish, ferns, and tree trunks. Surrounded by scholars and forest peoples, Rosi woke up early to assemble nets in igapó areas to capture birds for examination and weighing by bird specialists. She was so in harmony with nature that one bird “clung” to her and didn’t want to leave. Because of the encounter everyone started to call her the “bird charmer” during the expedition.

Biologists Fábio Quinteiro and Anne Costa, with UFPA’s Bragança campus, brought a variety of aquatic insects back on a tray of water. They rattled off their scientific names while the ribeirinhos told them about each one’s importance as a source of food. “When we lift a rock, the fish come in droves to eat,” they say. Fábio explained that this is why the bugs are known as bioindicators, organisms that are so connected to the environment they live in – their habitats – that any change can interfere with their life cycles and diet.

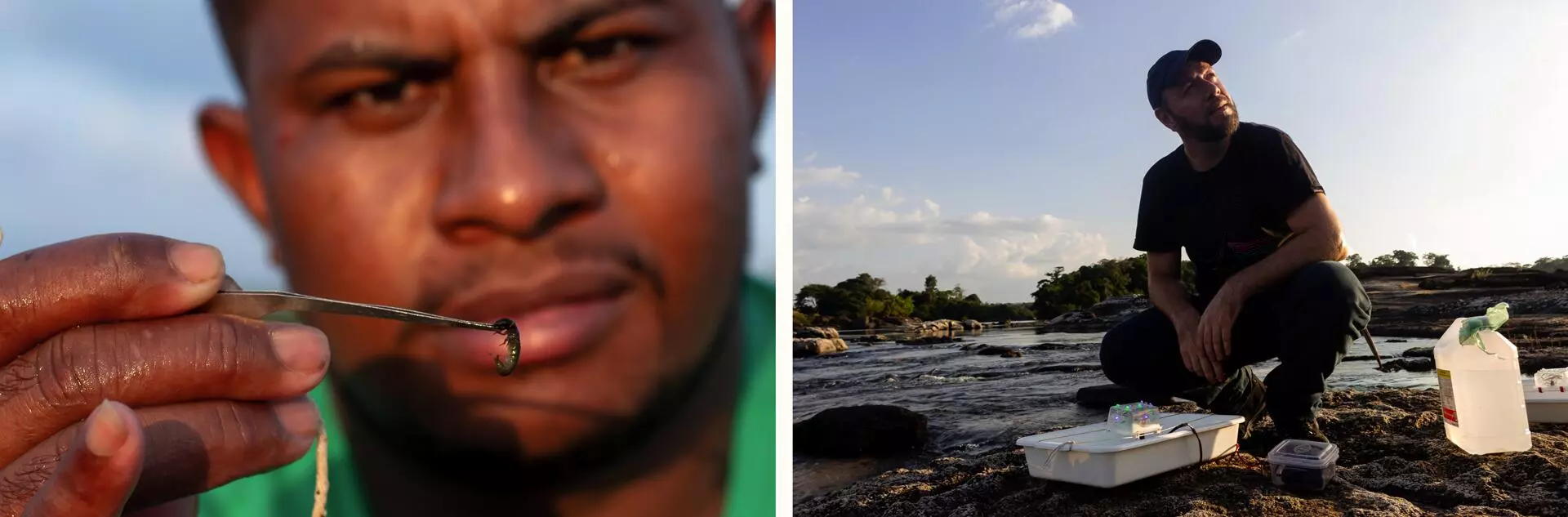

Josiel Juruna (left), a Mati coordinator, examines an aquatic insect. Biologist Fábio Quintero (right) highlights the project’s importance: ‘Looking at the insects is another way to see the river’

Water temperatures are substantially higher due to the low discharge caused by the Belo Monte Dam, which makes fauna nonviable for aquatic invertebrates. “Looking at the insects is another way to see the river. Nobody cares about the insects, but they’re important within this ecosystem. The idea is for us to notice that everything is interconnected,” Fábio explained.

An information war: what really happens on the river?

The cooperation, which started around a decade ago, between the independent monitoring done by ribeirinhos and Indigenous people and by academics has already resulted in significant changes to the licensing of the Belo Monte Dam. Based on data found by local researchers, which was compared to reports drafted by Norte Energia (the plant’s concessionaire), the academics produced several technical reports pointing to errors and inconsistencies in the company’s monitoring of impacts. Based on these analyses, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in Altamira then began to ask the licensing agency to respond and demonstrate accountability.

It was thanks to these joint efforts that Ibama, Brazil’s environmental agency, required additional studies to make clear which forests were being flooded and which were not because of the sequestering of the Xingu’s waters. It was only in 2019, four years after the Volta Grande region’s waters had been definitively deviated, that Ibama called for studies on how the reduced discharge is impacting floodplain forests, which in rivers with clear waters, like the Xingu, are known as igapós. These studies were finally completed in 2022 and ended up causing an about-face in licensing, by showing that most of the floodable forests were going dry. The total area of forests that no longer flood because of the river’s deviation varies, depending on which hydrological regime is applied to the Volta Grande: at 8,000 cubic meters, 70% of alluvial forests are lost; at 4,000 cubic meters, 80% of these forests go without water.

A researcher observes the dry and transformed landscape of the Xingu River. Scientists are troubled by the lack of any studies on floodable forests and want to monitor this phenomenon

Camila Ribas, a researcher with Inpa and one of the coordinators of the new studies now starting in Volta Grande, was behind a technical note dating back to 2020 that specifically recommended correcting this serious error in how hydroelectric plants are licensed on the Amazon’s major rivers: a lack of studies on floodable forests. “Floodplain forests flood annually. The flooding leaves behind sediments, creating nutrient-rich soil that is good for farming. These forests are home to many species found only in the Amazon. For these ecosystems to prosper, seasonal inundation is critical,” the note says.

“The disturbance in the Xingu River’s discharge that is affecting this region is still not being adequately studied. And monitoring is very important. The only monitoring with good results is the monitoring done by Mati,” says Camila. The researcher explains that a run-of-river dam “is a new type of dam in the Amazon where, instead of forming a large lake and affecting dry land, a long lake is created along the river bed (as is the case of the Jirau and Santo Antônia Dams) and deviation of the water in the area immediately below the dam (as occurs with the Belo Monte Dam).” As a result, Camila continues, the dam doesn’t just flood a large area of dry land, “rather it affects the entire extent of floodable areas.” It’s a unique hydrological solution. “Except that nobody was paying due attention to this in impact studies.”

With the “Sharing the water” project, researchers intend to survey critical data to contest the information produced in monitoring done by Norte Energia, information that is taken into consideration by Brazil’s environmental regulator, Ibama. So this is a battle of information and monitoring methodologies.

Scientists Camila Ribas (left) and Camila Duarte collect blood from the region’s birds for later study

“If you go to the floodplain and just count the number of species, ten species will appear in the area with reduced discharge, the same amount that was there before the impact. The number may not change, but the makeup of these species changes and this is not noted,” says the Inpa professor. In a unique environment like the Volta Grande do Xingu region, she says that “we have species we call specialists, which have evolved over millions of years and depend on cycles of flooding and drying.” When these species lose an environment, they disappear and are replaced with other, opportunistic species who come from elsewhere. “This also causes a homogenization of the biota (group of living beings in a certain place), in other words, a major loss in biodiversity. The biotas all end up the same and you lose general diversity. This simplistic analysis of counting species is much easier to do if you don’t want to see the impacts,” according to Camila.

The Mati group’s role in monitoring is crucial because the people living in the region notice environmental changes and are able to monitor what they see happening on a daily basis: they are skilled at producing data on inter-species interactions, on changes to organisms, on specimen quality. According to Camila, Norte Energia’s reports often conclude there have been no environmental changes from deviating the water. “It’s a testament to incompetency when all that work intended to monitor impacts can do is to conclude that there are no impacts,” the researcher sums up.

The reduced discharge imposed on the Volta Grande do Xingu region by the Belo Monte Dam affects the lives of fish and leaves behind dry pouteria trees (right), whose fruit feeds the animals

In a response sent by e-mail to SUMAÚMA, Norte Energia confirmed the researcher’s statements. The plant’s concessionaire says that “the impacts observed up to now, in the Volta Grande do Xingu region, in the ten indicators (water speed, sediment transport, flooded alluvial forest, fish, fishing, fishing yield, living conditions of fishers, navigability, mustelids, and turtles) are, as a whole, of a lesser magnitude than those set forth in the Environmental Impact Report.” The company also says the data it uses comes from “renowned scientists from public universities in Brazil, who are part of the monitoring list used by Norte Energia.” The names of these scientists were not, however, provided in the response sent to SUMAÚMA.

Fishing for little zebras

The “Sharing the Water” project, which started in the second half of 2023, makes it possible to monitor impacts on ornamental fish. The Yudjá are born divers, learning as children to stay underwater around rock outcrops and waterfalls in search of the little fish famous for inhabiting Volta Grande, which is home to nine endemic species (meaning they are only found there), including the coveted zebra pleco. Lovingly called “little zebras” by the region’s residents, this fish can fetch up to R$ 2,000 each on the international market and used to be an important source of income for local communities – who received a small fraction of their market value, around R$ 60 per fish.

Since 2004, the capture of zebra plecos has been banned in Brazil, with sales of the fish regarded as wildlife trafficking. Yet contraband has this characteristic: the more threatened the species, the more valuable it becomes. And the Belo Monte Dam is a direct threat to the zebra pleco’s habitat. They depend on flooding of what locals call sarobals – the floodable vegetation around waterfalls and rapids. These fish are known for being shy, because they hide in rock outcrops, and they need fast-moving and heavily-oxygenated water. Because the discharge was deviated, the characteristics that make a sarobal are being lost.

The Yudjá have noticed the tiny fish are missing. When they saw that the population was rapidly declining, they took it upon themselves to create a protected area for the zebra plecos, periodically observing their reproduction. Jailson Juruna, a resident of Pupekuri Village and an expert on this ornamental fish, will coordinate monitoring work for this species.

Jailson Juruna uses a cast net to catch fish in the rapids of the Xingu River, which the project will monitor and analyze

Jailson has been diving in the waterfalls since he was eight years old. “At six in the morning I’d wake up and I’d already be itching to go to the river to dive. At noon, I’d go to the lakes to shoot fish with arrows for lunch,” he says. None of this exists any more: “We can no longer catch fish with arrows, or with fishing poles. We used to pick which fish we were going to shoot with arrows. On a day where I wanted to eat pacu, I just caught pacus. Because there was lots of food for the fish on these islands and in the piracemas [fish spawning grounds] as well. We would smack the branches to make the fruit fall. There were figs, camu-camu, yellow mombin plums, tucum palm fruit. We would hit them, they would fall in the water, the fish would come in droves. And we would pick out our lunch.” Now the fruit falls on the dry ground. “And lots of trees began to dry out. We walk along the river and the places are all dead, dry, dry,” says Jailson, shaking his head, his eyes cast downward.

Project coordinator Janice Cunha, a researcher at UFPA’s Bragança campus, explains that the memory of the river’s wet and dry periods, which is part of the evolutionary history of species, is also part of the history of the Xingu River’s ribeirinho and Indigenous communities. “It’s a synchrony of life that no longer exists. We want to monitor what this synchrony is. The ribeirinhos and the Indigenous people talk about a tidal effect, as if there were a sudden increase, sometimes a few centimeters, sometimes many meters over the period of a year, that not even the fish, or the ribeirinhos and Indigenous fishers were accustomed to.” She explains that monitoring will check the kind of effect these sudden changes cause in these relations between the communities and the river.

Janice highlights the scientific importance of the work local researchers are doing. “They are doing science based on their own hypotheses. And they’ve been doing very dedicated data collection, with a persistence and a frequency that practically no research center is capable of doing. Because they do it as they are collecting or fishing, day to day. Few research groups are able to do this in the world, it is a very significant volume of data,” she reiterated.

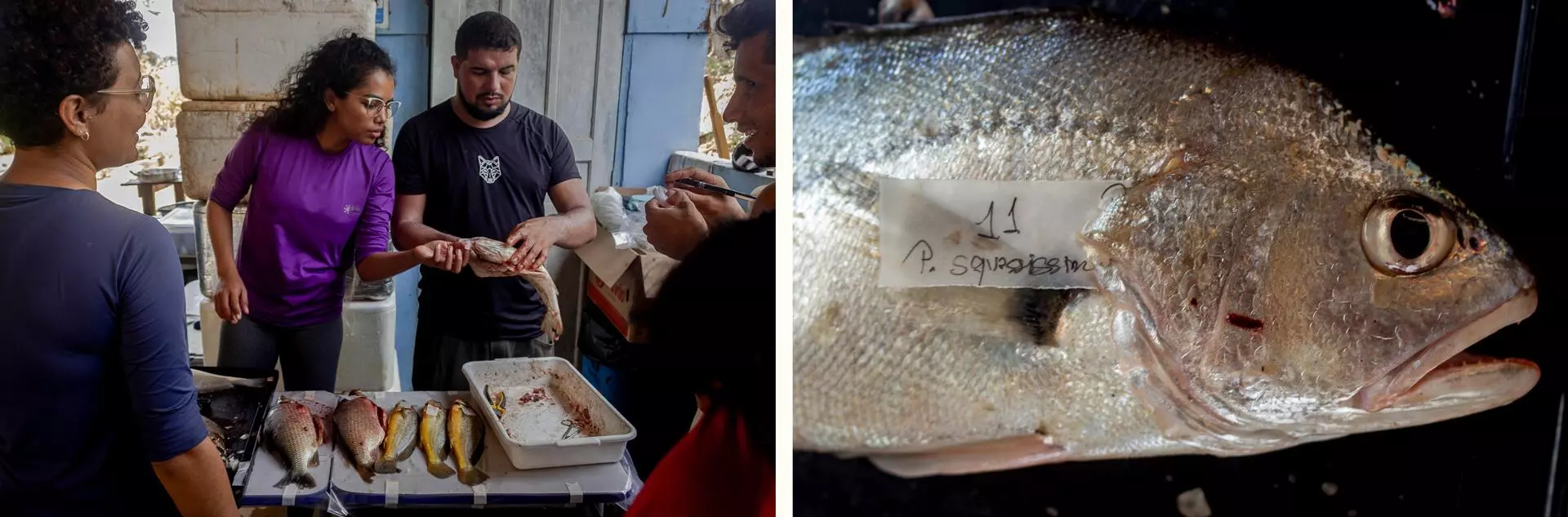

Monitors remove tissue and intestine samples from Volta Grande do Xingu area fish for scientific analyses

After collecting data in Mïratu, a team headed to the Cachoeira do Espelho region, 96 kilometers from the main dam in the Belo Monte complex. There, data was collected on the same variables and bioindicators observed in the Volta Grande region, for comparative purposes. The region was chosen because it is close enough to have the same types of ecosystems and far enough away not to have suffered the most direct impacts from the plant. This comparison will finally provide a more accurate scientific picture of the damage caused by the sequestering of the Xingu River’s waters. Another project coordinator, André Sawakuchi, who is with USP, will collect geological and hydrological data at a future stage of the project.

The deathtraps catching the fish

At Volta Grande do Xingu, sorrow and the signs of disaster are everywhere, even if official monitoring seems incapable of detecting them. Hundreds of puddles form among the rocks, due to the variation in the river’s discharge, trapping thousands of fish. SUMAÚMA accompanied a team of researchers to the Paraíso Sarobal, 1 kilometer from Mïratu Village. Before the Belo Monte Dam was built, this was one of the Yudjá’s preferred fishing grounds, but now it is a deathtrap for the fish.

The Xingu River is normally a balmy 29 degrees Celsius. In the water the Belo Monte Dam has turned to puddles, the temperature was approximately 40 degrees Celsius. Some are greenish in color, indicating eutrophication; put another way, the proliferation of algae sucks all the oxygen out of the water, making it impossible for aquatic species to survive.

The scientific expedition also cataloged fish found dead from the Xingu River’s lack of water

Hundreds of fish, including juvenile fish, are stuck in these puddles, waiting for certain death from the heat, a lack of food, or a lack of oxygen. “Spawning did happen in the river’s main channel, but with discharge and flooding now being artificially controlled by Norte Energia, these scorching puddles form that trap the fish,” explained Janice Cunha. By stopping the flow of water, the Belo Monte Dam has also stopped the flow of life for many species in the Volta Grande do Xingu region.

The group’s guide, Ya Juruna, whose father is the cacique of Mïratu Village, lets out an anguished cry. The researchers and reporters have come across a puddle filled with dead or dying fish, juvenile fish in the throes of death inside of the scorching hot water. The team removed fish to measure and photograph them, the little that could be done in the face of this catastrophe.

“I heard the sound of leaves in the puddle. I thought they were little frogs. When I looked, there were a bunch of little rhombic mojarras, caracids. All dying. They’re asking for help. And every year this happens. Last year, the year before last. I try not to cry. I try to be strong, but it’s tough, because it’s life, right?” laments Ya Juruna. She can’t understand “why people want to build a dam and get rid of life.” “I don’t know why people don’t care about this. Why is the human being more important? Because life is life, you know? A plant, when it’s hurt, if you care for it, it returns to how it was before. So Volta Grande can still recover. There’s no way for it to go back to being like it was before, but it can still resist. We can protect at least a bit of this life,” Ya advocates, between disillusion and hope.

Ya Juruna, a village resident, tries to stay strong when she sees so many fish suffering: ‘All dying. I try not to cry. I don’t know why people don’t care about this’

According to Ibama, there is a monitoring and rescue program for fish trapped in puddles. The technical team confirmed that this phenomenon has intensified because of the discharge variations caused by the plant’s operation and that from 2015 to 2022, 9,500 kilos of fish were rescued while around 350 kilos of fish were found dead in these locations.

Grieving the piracema, leafcutter ant nests appear instead of fish

At the Zé Maria Piracema, also near Mïratu Village, the team found giant leafcutter ant nests where there used to be a fish spawning ground. The ants leave well-tread paths on the ground littered with dry forest leaves. Far from being villains, the presence of these ants is just one clear sign of the change in the environment: they shouldn’t form nests here, because the forest is floodable, an igapó, that is supposed to be overtaken by the Xingu’s waters at least six months out of each year. Yet the Zé Maria Piracema has gone eight months without flooding. This chronic drought gave the leafcutter ants time to build large nests, which would not happen if there were water. These are the types of environmental signs that the researchers are looking for in the project being done through a collaboration between the Mati and Amazônia +10.

The Zé Maria Piracema should start to flood early in the region’s rainy season, in November. This has never happened again, because of the hydrogram imposed by the Belo Monte Dam. Researcher Sara Rodrigues, a member of the Mati and a participant in Micélio – a SUMAÚMA co-training program for forest-journalists – explained that this location has its first “header” from December to January. A header, she explained, is the term used for the arrival of the schools of fish who go up to the igapós to spawn. It’s a descriptive term, directly related to the thousands of fish heads that join together in the race toward the piracemas.

The scene, narrated by Volta Grande’s residents, is also set to a soundtrack. On their way up to the igapós, streaked prochilod males make a sort of grunting noise. In the local language, they start “booming” as they near the spawning grounds.

Today, the vision of the headers is but a memory, and the boom of the streaked prochilods is no longer heard. When talking about the moment the fish spawn, something they have witnessed and understood since they were children, the monitors take a solemn tone, as if they were speaking at a funeral. In the middle of the dry piracema, a large rock has become a pulpit. “November will come, the female fish will be there, full of eggs, but there will be no water in the piracemas to lay them. We explain this to Norte Energia and they say it’s normal,” says ribeirinho Paulo Ferreira, who is with the Mati group.

Specimen collection, water quality analyses, and assessment of ecosystem resilience: researchers split into groups on the expedition, with specific jobs

“We, us and the fish, are living this whole time with 20% to 30% of the water we had before. How can they say that there are no impacts?” asked Sara Rodrigues. “The waters that would normally rise in November are only rising in March. The fish are no longer able to spawn or find food. My father says that he would find fish so fat they would get stuck in the rocks for us to catch. Now we only find skinny fish,” added Jailson Juruna.

Atop the pulpit-rock, the residents list the types of fishing they can no longer do because the Xingu’s waters are being held back, and they recall a time when mothers weren’t afraid to have many children, because the river would sustain them.

For the return of the Volta Grande

While waiting for November to arrive, the piracemas can still be saved for the next year. It depends on Ibama’s acceptance of a hydrogram (water management plan) proposed by the Indigenous and ribeirinho researchers in the Mati group, along with the university researchers, one that would let the fish spawn. The licensing agency has had this proposal since December 2022, for nearly one year now, having received it during the last presidential administration. Ibama told SUMAÚMA by e-mail that “the criteria indicated” in the proposal “are relevant and the subject of technical consideration in the agency’s assessments, since they reflect the traditional knowledge and perception of the region’s Indigenous and ribeirinho communities.”

Since October, the residents of Volta Grande do Xingu have begun a countdown for life, while they wait for a response from Brasília. “The federal government’s motto is ‘Union and Reconstruction.’ We hope that reconstruction also applies to Volta Grande, because it was the government that destroyed it,” says Sara Rodrigues, recalling that the Belo Monte Dam was licensed under the Lula administration and built under Dilma Rousseff.

Redefining how the waters are shared among the hydroelectric plant and the ecosystems is the only way to protect life. Without the piracemas, there is no life. Because fish and trees cannot speak for themselves, Sara Rodrigues says that she will never let this pain be silenced: “We will always represent for the fish, for the rivers, for the little birds’ trees, for everything.”

The story was updated with a correction at 5:30 PM on October 27, 2023: the Santo Antônio and the Jirau are also run-of-river dams, like Belo Monte, but they do not deviate water; in other words, they have no areas with reduced discharge like the areas around the plant. This information has been updated.

Reporting: Helena Palmquist

Photos: Soll Sousa

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreading (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya (editorial workflow and copy editing assistant editor)

Editors: Malu Delgado (news and content director), Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing)

Director: Eliane Brum

Ronald Juruna, the bowman on the expedition, looks out onto the river. Every life form seems to have been affected in the region after the Belo Monte Dam was built