1. What is the marco temporal (historic cut-off point) ?

It is a legal argument that only those lands that were occupied by Indigenous people when the Brazilian Constitution was enacted, on October 5, 1988, can be demarcated. In short: only the people who were in the areas on that date can claim title to the land. This approach ignores the fact that a number of Indigenous groups and villages were expelled from their territories and persecuted at that time.

2. When and how did this timeframe ruse arise?

The timeframe ruse was already known in legal circles prior to the 1988 Constitution. But it was only in 2009, when the Federal Supreme Court judged the demarcation of the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land, which is home to the Macuxi, Taurepang, Patamona, Ingarikó and Wapichana peoples in the state of Roraima, that this argument became better known in Brazil.

3. What are the legal arguments for and against?

Article 231 of the Constitution establishes that Indigenous people will have permanent possession of lands traditionally occupied by them. According to this view, the original right over the land, recognized in the Constitution, prevails: the Indigenous people were here before Brazil came into existence. Those who dispute the timeframe thesis claim it will unfairly provide “legal security” for the land’s current occupants, many of whom acquired the land illegally, via the theft of public lands. Those who advocate a limit maintain that traditional possession should not be confused with “timeless ownership” and legal clarification will help avoid conflicts.

4. Can the cut-off point be imposed by a bill or is it necessary to change the Constitution?

PL 490, which was approved by the House, is a bill, in other words it just needs a simple majority to be approved (more than 50% of the votes of those present on the day of the vote). But the timeframe thesis alters the Constitution’s fundamentals, set out in article 231. For this reason, critics say this matter could only be debated as a proposal to amend the constitution (known by the acronym PEC), which can only be approved by an qualified majority (at least 308 deputies and 49 senators). On the basis of this interpretation, PL 490 is unconstitutional.

5. If the Federal Supreme Court approves a cut-off point, what happens to the demarcation of Indigenous lands?

It all depends. If the ministers of the Federal Supreme Court decide the cut off point is October 5, 1988, the original peoples will need to prove they were in their territories or disputing them on that date. If they cannot prove this, they will not be entitled to the land. Another possibility is the ministers may propose a “consensus solution,” setting the cut off point at 1934 – the year of the first Constitution that recognized Indigenous peoples’ rights. If this were to occur, the original peoples would have to prove that they were occupying their lands (or at the very least were disputing them) as at this date – which is also very complex, according to legal scholars and Indigenous people.

6. If the Federal Supreme Court overturns the cut-off point argument and Congress then insists on changing the Constitution in order to impose this rule, what could happen?

The most likely outcome, in this situation, is that the case would return to the Federal Supreme Court for a new judgment. Critics of the time limit argue the Indigenous peoples’ rights to their territories are an irrevocable clause – in other words, one that cannot be altered even by a constitutional amendment.

7. If the time limit is approved (by the Federal Supreme Court or Congress), how could the demarcation processes currently underway be affected? How many are there?

It all depends on what cut-off point is established and how it might be challenged for example, if the time limit were established by ratification in the Senate or by a new constitutional amendment. In theory, if the cut-off date were set at 1988, around 300 land demarcation processes could be affected and halted.

8. Why are the members of the ruralist (agriculture) lobby rushing to pass a time-limit law before the Federal Supreme Court sits in judgement on the issue?

This is a political move. The ruralist lobby wants to flex its muscles and prove that Congress has the autonomy to define the rules for demarcations, rather than the Federal Supreme Court. It is also a way of putting pressure on the Judiciary before the judgment on this subject, which is hard to predict. But it should be stressed that there are so many doubts about the constitutionality of PL 490 that the Federal Supreme Court has not canceled the judgment.

9. Why do politicians say that the Raposa Serra do Sol judgment, back in 2010, has already established a precedent for a demarcation cut-off point?

The predatory agribusiness sector cites this judgment because that was when the Federal Supreme Court addressed the timeframe question. The rapporteur at the time, Minister Carlos Ayres Britto, voted in favor of the continuous demarcation of Indigenous land and the removal of non-Indigenous people from that territory. But he also declared, that in the future it would be necessary to define a timeframe. The important thing is the court made it clear that what was judged and decided about Raposa Serra do Sol would not apply to other Indigenous lands in Brazil.

10. Why is the demarcation process the responsibility of the Federal Government, rather than of Congress, and why should this remain the case?

Because that is clearly stated in the Constitution, which is the country’s highest law. Contrary to what the ruralist lobby says, the demarcation process is a technical one, which involves permanent civil servants who work for the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai) and other public entities, and there is ample room for questioning by those who believe they have been wronged. If it becomes the responsibility of the Legislative Branch, demarcations will become a political issue – and that is exactly what the ruralist lobby wants, because they will then control the demarcation process and the promise that the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro made and kept during his four years in office will come back into force: not a single centimeter more of land will be demarcated for the Indigenous peoples.

*Text updated on June 15, 2023. In question 4, the original article stated incorrectly that an absolute majority is required to approve a Proposed Constitutional Amendment (PEC). The correct information is that passage of a PEC requires a qualified majority, that is, at least 308 deputies and 49 senators.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

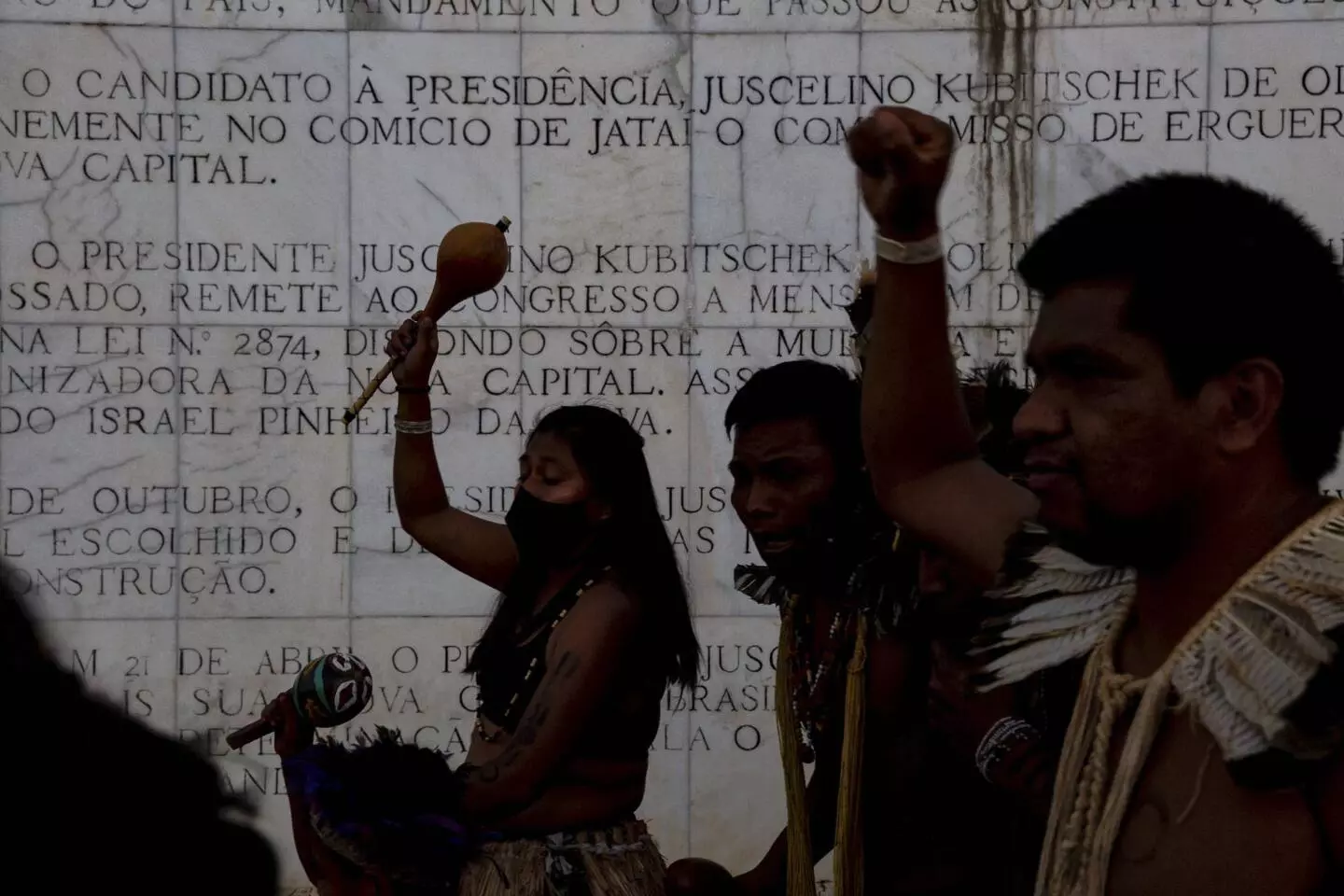

IN 2021 INDIGENOUS LEADERS MARCHED IN PROTEST TOWARDS THE FEDERAL SUPREME COURT. THIS WAS THE YEAR IN WHICH THE JUDGMENT BEGAN THAT WILL INFLUENCE THE DEMARCATION OF ALL INDIGENOUS LANDS IN BRAZIL AND DEFINE THE FUTURE OF DEMARCATIONS. PHOTO: Tuane Fernandes/Greenpeace