In December 1995, a group of scientific experts called on by the United Nations published a historic document confirming climate change was a real problem, while also stating that there was “a discernible human influence” on the climate. In the following decades, 99% of the world’s studies on the topic would come to agree that the burning of fossil fuels was warming the planet and making extreme weather, like downpours, droughts and hurricanes, more frequent and intense. Nevertheless, in May 2024, nearly three decades later, while southern Brazil is inundated by its worst flooding ever, another flood has also hit the region and is spreading across the country: climate denial.

According to a report issued by the Democracia em Xeque Institute, a partner of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, from May 7 to 13 alone, the topic of flooding in Rio Grande do Sul appeared in 7.7 million social media posts (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, X, and TikTok). Out of these, 4.3 million posts, or more than half, involved disinformation. Most of these were posts containing conspiracy theories and climate crisis denial, as well as polarizing narratives – those that ratchet up political disputes amidst tragedy. The report’s authors also found that 75% of this content came from the far-right.

Similar conclusions were also drawn in a document produced by NetLab (as the Internet and Social Media Studies Laboratory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro is known), which provided a qualitative assessment of the most popular fake news items in circulation from April 27, when rains hit Rio Grande do Sul, to May 10, 2024. One of the authors on the study, NetLab researcher and director Marie Santini, pointed out that, among the main narratives put out by disinformation spreaders, are those navigating the relationship between extreme rainfall and climate change, those ascribing a moral agenda to tragedy, and those pointing to an insufficient government response. The report also confirmed that “far-right influencers, websites, and politicians have used the commotion to self-promote and spread disinformation, aimed at attacking the government and raising doubts about its credibility.”

Videos about donations supposedly being blocked because they lacked invoices were shared and hampered the distribution of aid to victims. Photos: Screenshots

For example, one video shared thousands of times showed a factory in China producing rice-like grains and featured text that said the Lula administration had decided to import food made out of plastic to meet demand in the Brazilian market. The post was discredited by a variety of fact-checkers, including those at Reuters. While another video that also went viral, made by a doctor who is a supporter of former far-right president Jair Bolsonaro on social media, said Brazil’s health regulator, Anvisa, had blocked private planes carrying medications from landing in more than three airports in the capital city. The regulator immediately denied the claim. Much of this fake news even hinders help from being sent to victims. This includes posts claiming donations are being denied because they lack invoices, vehicles transporting supplies from other states are supposedly being fined, and rescue boats and jet skis driven by unlicensed people are allegedly being impounded.

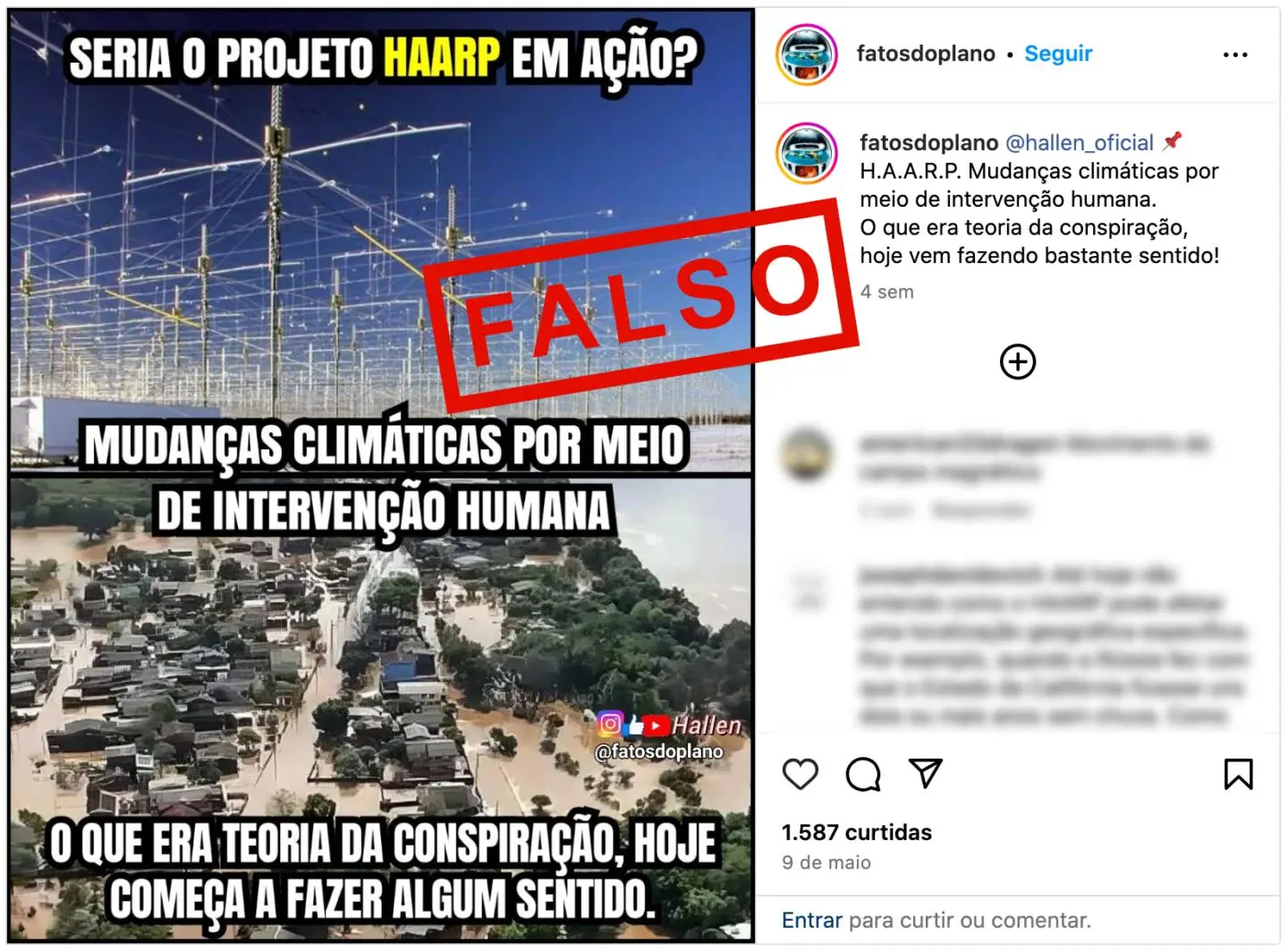

Among posts denying climate change’s influence on the flooding was one attributing the catastrophe to the United Nations’ Agenda 2030, with the idea that it is purportedly a movement to implement a “global and totalitarian government” that is allegedly controlling the weather. Posts also blame flooding on Haarp antennas used as part of a U.S. research project. According to this conspiracy theory, the project, which is studying a layer of the upper atmosphere known as the ionosphere that is far from the layers where clouds and weather phenomena form, is supposedly causing rains in the country’s south to sow fear, confusion, and outrage, thus instituting the interests of “high-power groups.” The Haarp project has already been used to justify other extreme weather events and was even accused of sending rain to sabotage camps set up in front of barracks to support former president Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party).

Conspiracy theories like one claiming the Haarp project is responsible for rain in Rio Grande do Sul spread across social media. Photo: Screenshot

The relationship between a disaster’s intensity and growth in disinformation, which caught many by surprise and even hampered rescues and the distribution of supplies in Rio Grande do Sul, is nothing new. It is just another chapter in a long, complex, and intricate network of climate denial that has for decades taken advantage of precarious times, when populations are at their most vulnerable, to reinforce narratives that benefit certain political and economic groups. The modus operandi of this “denialist machinery” is simple: keep allegations grounded on misinformation that, for some time, has failed to stand up to scientific rigor and then circulate and repeat indefinitely. Brazil’s far-right, appearing as a leading player in the most recent chapter, is just one piece in this puzzle.

“Every time we see a climate disaster, it reminds people that climate change is real, that it’s happening here, now, and it’s hurting and killing people. For precisely this reason, far-right and pro-fossil fuel forces around the world are immediately coming onto the scene to create confusion. This happened after Hurricane Katrina, in the United States, and it’s happening now in Brazil,” says Naomi Oreskes, a science historian and professor at Harvard University.

Yet why do so many also people buy into climate crisis denial, even with science providing so much evidence. What is the strategy keeping this narrative alive? And what are the interests behind it? Oreskes, who is also one of the authors of Merchants of Doubt – a book that delves into the history of the secret machinery of climate denial – says that to understand the scenario now, you have to go back in time to December 15, 1953.

Doubt is our product

It was a frigid December afternoon when executives from the world’s big four tobacco companies (American Tobacco, Benson & Hedges, Philip Morris, and U.S. Tobacco) anxiously met in a bar at the luxurious Plaza Hotel. They were worried about the publication of recent scientific studies that were starting to point to consensus on the idea that smoking caused cancer. Taking part in the meeting at their request was John Hill, from Hill & Knowlton, regarded at the time as one of America’s public relations gurus. It was Hill who took note of the meeting details that would later become public. The executives were legitimately worried: these studies were being published in the popular magazines of the day and were threatening their lucrative business.

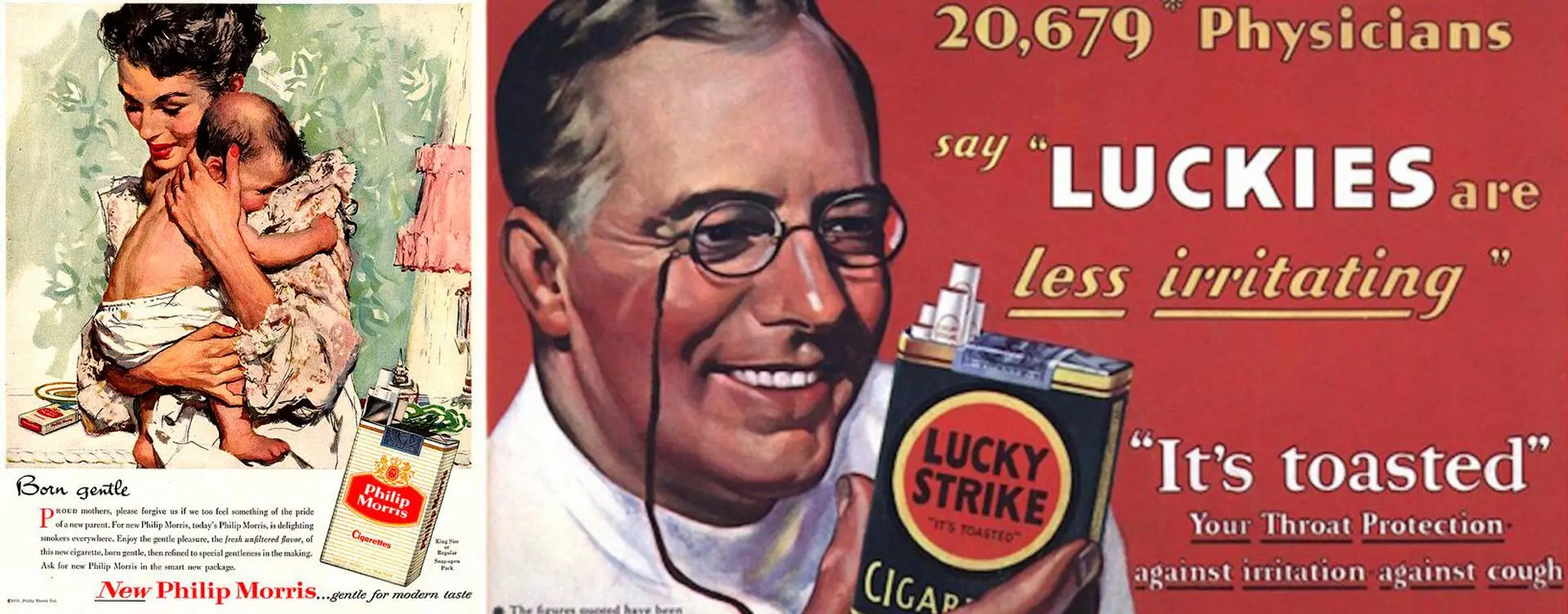

Hill realized there was no fighting facts – but sowing doubt about them was possible. The idea was simple: question studies that drew a relationship between smoking and cancer and produce new “scientific” evidence that would relativize these discoveries. This new evidence, Hill suggested, would come from a committee of specialists that would contribute opposing views to the public debate. The executives bought in to the idea, and for the next five decades they followed the proposed handbook: they created a “Tobacco Industry Research Committee,” which took snippets from research results (selecting only those sections that were convenient) and used them in deceitful campaigns on which they spent millions to sow doubt among the public. Along with this, the press was used as an ally. Making an argument that serious journalism should always hear “both sides of the story,” they insisted that industry-bankrolled researchers and doctors should take part in fostering live debates, creating a false sensation that the relationship between cigarettes and cancer was controversial. This created one of the most successful marketing strategies ever. Over decades, no lawsuit against the tobacco companies managed to move forward, and it took nearly 50 years to implement the first regulations on the industry.

The strategy used by the tobacco industry was repeated countless times, in different versions of denial. It was used to question the origins of acid rain, the existence of a hole in the ozone layer… And it is used to this day to deny climate change, its causes and its consequences.

Old cigarette ads misinformed the public about the scientifically-proven harms caused by tobacco. Photos: Screenshots

Keeping controversy alive

The next chapter in this story starts in the late 1970s, when studies on climate change and on the human influence over this process were starting to gain traction – and to worry large oil companies. The idea that greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels could be leading to the planet’s warming – and that the consequences of this could be serious – posed a risk to business for major oil companies like U.S.-based Exxon and Mobil (which later merged, forming the Exxon Mobil Corporation).

Concerned about possible government regulations to control and tax emissions, these companies began to look for strategies to mislead public opinion. That was when they found an ideal plan in the tobacco industry’s playbook.

Just like the executives at Philip Morris and other large companies in the industry, representatives from the fossil fuel behemoths created committees and think tanks (institutions dedicated to producing knowledge on political, economic, or scientific topics) whose aim was to produce reports and lend credence to experts questioning climate change. To do this, they took advantage of an important characteristic of the scientific process: consensus in the field of science comes from a collection of studies that oftentimes take years or even decades to provide clear and definitive answers on a given subject. It was these “temporary gaps,” or rather, the points regarding the planet’s warming that had not yet been completely clarified, which the denialists used to sow doubt.

Not only were the same tactics used as those employed by big tobacco, but some of the same characters showed up again. Two of the scientists leading debates questioning the harm of cigarettes, Fred Singer and Frederick Seitz, reappeared a few decades later to head meetings denying the climate crisis. Whenever a new study on this topic came out, these researchers went into the field, occupying space in popular newspapers and TV shows to rekindle doubt.

Further taking advantage of the historic moment, in which the U.S.A. was living under the shadow of communist threat, these scientists began to associate environmentalists with communists. The argument was: climate science defenders had a hidden agenda to destroy the country’s economic model, which was sustained by large fossil fuel companies. The idea advocated by environmentalists, that greenhouse gas emissions should be regulated, was seen as a threat to the free market and this model of development. These arguments fit the far-right like a glove, which then began to appropriate the discourse of climate denial and to defend it.

As climate science progressed and filled in the gaps still generating debate among scientists, denialists were also adapting their own narratives. “First, they said climate change didn’t exist, then they said that temperature fluctuations were a natural phenomenon, and then they began to argue that, with changes occurring and despite this being our fault, it didn’t matter because we would always be able to adapt to them,” Oreskes says.

In 1995, when the group of scientists at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released their report affirming there was a “discernible” human impact on climate, denialists were publishing their own reports questioning parts of this topic where there was already consensus, pointing to supposed conspiracies involving panel members and hidden interests, in addition to making ad hominem attacks (criticizing the authors and not their studies) against qualified scientists or public figures committed to mitigating climate change. Many of these strategies were intensified at key moments in global climate negotiations, hobbling advances in climate commitments between countries.

Over decades, large companies took advantage of and fed groups that denied climate science to, in the words of one Exxon (now ExxonMobil) internal memo from 1988, “emphasize the uncertainty in scientific conclusions regarding the potential enhanced greenhouse effect.” This alone would already be considered extremely serious. Except it was even worse. An article published in the journal Science in January 2023 showed ExxonMobil had, since 1977, been carrying out internal studies whose forecasts for the planet’s heating were consistent with those projected by academic studies. Put another way, their own scientists were confirming that climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels represented a dangerous scenario, yet even so the company invested millions in ads, propaganda, and debates that cast doubt on this reality. In reporting on the case, the company denied the accusations.

Protests against Exxon Mobil, which had known for decades that fossil fuels were affecting the climate. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images via AFP

A tactic imported to Brazil

The climate denial model established by large American corporations did not take long to spread its wings and find supporters in other countries. In Brazil, it landed with greater force in the 2000s, adapted to the local reality – and with its own cast of characters. Brazil is one of the world’s five biggest greenhouse gas emitters. Except that here, unlike the other large emitters, the main culprit is not the energy sector, but rather agriculture and deforestation, according to the most recent System for Estimating Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals report. This is why it is no surprise that more conservative sectors in agribusiness, spurred by a far-right that spreads fear of “environmentalist communism,” is playing an important role in this disinformation process.

In an article published in Sociedade e Estado, a journal published by the University of Brasília, sociologist Jean Miguel, an associate professor in the Department of Science and Technology Policy at the Institute of Geosciences at the University of Campinas, says early arguments opposing scientific consensus on the climate crisis began to gain traction in the country in 2007 and grew stronger through the work of a small yet loud group of academics, who began to play a role similar to the one played by researchers Fred Singer and Frederick Seitz in the U.S.A. Here, it was Ricardo Felício, a professor of geography at the University of São Paulo, Luiz Carlos Molion, a meteorologist and retired Federal University of Alagoas professor, and agronomist Evaristo de Miranda, who took the stage at events promoted by sectors of agribusiness and took part in national congressional debates on environmental legislation, oftentimes at the invitation of the ruralist bloc, as reported by Agência Pública. The line defended was the same: the lie that there is no consensus on climate change and there is no evidence that man is chiefly responsible, which is in opposition to the science. This fallacy is used to justify inaction. Based on it, members of congress claim it is meaningless to implement laws regulating greenhouse gas emissions and they therefore perpetuate the tragedy.

For example, an investigation published in 2023 by journalists with the Brazilian branch of German newspaper Deutsche Welle showed researchers in Brazil questioning data and reports generated by Evaristo de Miranda and his team at Embrapa, a government-backed agricultural research company, which exempted large producers from responsibility for the Amazon’s destruction, while scientific analyses published in respected periodicals showed the contrary. “The most conservative sectors in agribusiness saw this disinformation strategy as a strong ally to bend norms to protect forests and weaken the Brazilian government’s commitment to international agreements reinforcing the need for stricter policies to control deforestation,” Miguel explains.

Evaristo Eduardo de Miranda, then the chief-general of Embrapa’s geospace research unit, became an adviser to Bolsonaro. Photo: Marcos Oliveira/Agência Senado

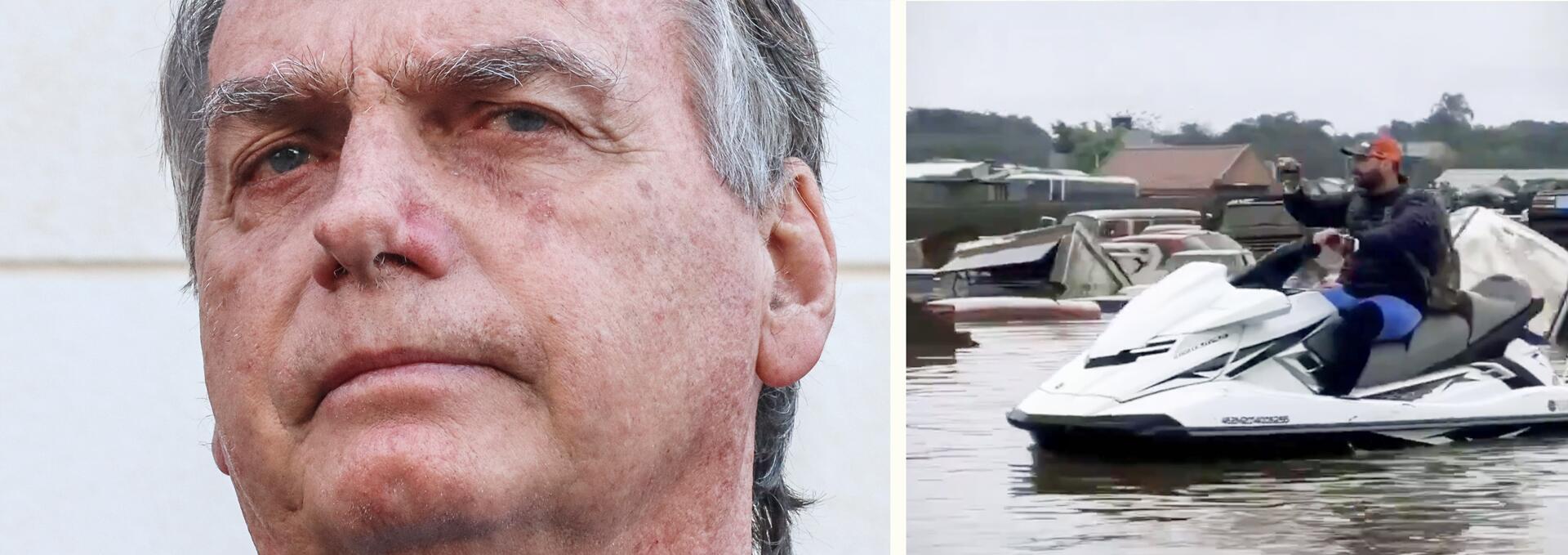

Even outside of his role as president, Jair Bolsonaro and his family remain active when it comes to denialist narratives. In the recent case of Rio Grande do Sul, federal deputy Eduardo Bolsonaro’s (Liberal Party) social media profiles were highlighted as major spreaders of disinformation about the flooding, according to a report issued by the Internet and Social Media Studies Laboratory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. The far-right former president’s son, who was in the country’s south – where he appeared in videos riding a jet ski to show damage caused by flooding – was one of the people sharing fake news about the federal government blocking trucks with donations. “Although this news was debunked, the deputy insisted the left and [the TV network] Globo were spreading fake news by trying to ‘mask the reality’ of the donations being blocked,” the report from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro points out.

In 2023, Bolsonaro was called to answer Federal Police about ‘fake news.’ This year, his son Eduardo spread misinformation about floods. Photos: Valter Campanato/Agência Brasil and screenshot

Vaccinations against disinformation

As if enhancing disinformation strategies were not enough, narratives denying the climate crisis have recently reached new levels with the popularization of social media. In a 2018 article published in the journal Science, researchers at the Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed online disinformation has a greater reach and spreads much faster than true information, and one reason is a lack of traditional moderation models. “Social media has made a significant contribution to strengthening climate denial, serving as a platform to intensify and spread narratives that have already taken root in certain sectors of the media and culture,” explains researcher Lori Regattieri, a member of the Coalition for Independent Technology Research. That is why researchers have spent years trying to find the best strategies to fight these narratives.

John Cook, a senior researcher at the University of Melbourne and the founder of the Skeptical Science website, one of the main channels fighting climate denial in the world, has been leading research along these lines. In the Conspiracy Theory Handbook, a report written in partnership with psychologist and researcher Stephan Lewandowsky, a professor at the University of Bristol, in the United Kingdom, he argues that if people know about the most popular disinformation strategies, they can become immune to this fake news. “It’s as if you were vaccinated against disinformation. When you understand the erroneous reasoning and can identify it, you become less vulnerable to that lie,” says Cook.

Naomi Oreskes backs this idea, and adds that “the best way to fight disinformation is by naming it and exposing the person spreading it. When people understand that something is disinformation, this has an inoculating effect, it works like a vaccine. It’s an important step, but identifying who is spreading this fake news and revealing that person as dishonest has also proven effective,” she explains.

In an effort to educate the public on this topic, Cook has systematized a method to identify the five main elements that characterize denialism, which are known by the acronym FLICC, referencing the first letter of each of the disinformation strategies (see the chart below). The technique of “vaccinating” people against these narratives was tested and documented in an article published by Plos One, a freely accessible science journal put out by the Public Library of Science. In the study, the authors showed that inoculation, or rather, recognition of disinformation strategies, was capable of “neutralizing the negative influence of the misinformation.”

For Oreskes, the public has already made progress in understanding what the climate science says and the need to implement urgent measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Nevertheless, she says this awareness is not evolving at the same pace as the problem. “It took almost half a century to unmask the tobacco industry. But when it comes to climate change, we don’t have the same time,” she says in closing.

The five tactics climate disinformation

F: FAKE EXPERTS

This strategy refers to scientists or researchers who speak with supposed authority on topics on which they have no expertise. Many of them go public with stances opposing matters that have already achieved scientific consensus, such as climate change, creating a false sense that the topic is still up for debate. Fake experts generally attack actual experts, whom they accuse of being bought or sold by certain groups or companies.

L: LOGICAL FALLACIES

These are defective standards of reasoning. They consist of invalid arguments that, at first glance, can seem persuasive. Some common examples are the argument that the climate has always changed due to natural causes throughout history, and today’s changes are also due to natural causes; or that because the greenhouse effect is fundamental for life on Earth, a rise in these gasses can’t be bad. This technique is also known as “jumping to conclusions,” or rather, connecting a cause to an effect without knowing if there is actually a relationship.

I: IMPOSSIBLE EXPECTATIONS

This is the idea that absolute truths must be demanded in science, something that is completely infeasible, since science is a sort of open book. Each scientific study provides new elements that help to direct, confirm, or refute a theory. When most research points to the same thing, as is the case with climate change, then we say that a scientific consensus has been reached on the matter. Nevertheless, denialists use questions like “scientists can’t even forecast the weather for next week correctly, how will they forecast the climate a decade from now?” to create doubt and confusion. There will be uncertainties in classic meteorology, since it depends on complex measurements. Yet this doesn’t have anything to do with the methodologies used in climate change studies.

C: CHERRY PICKING

This is a type of fallacy where information is only shared when it favors an argument being made, hiding other data that are part of that reality. The result is a scenario that is very different in the broader context. The idea of “picking cherries” illustrates this well. When harvesting cherries in the field to see how the cherry crop is doing, the person doing the harvesting can purposefully pick only the ripest and healthiest fruit. Someone who sees this fruit sample will tend to think that the crop is good. However, this selection can’t always be seen as representative; that is, it isn’t necessarily an actual snapshot of this crop’s situation.

C: CONSPIRACY THEORIES

This is the strategy of creating an idea that there is a hidden interest behind scientific consensus, such as on climate change. One example is the claim that the environmental cause is a tool being used by communist leaders to topple the capitalist system. Another quite common one that began to circulate during the flooding in Rio Grande do Sul is that a U.S.-backed scientific project called Haarp, which is studying physical phenomena occurring in the upper layers of the earth’s atmosphere, is supposedly responsible for rains in the country’s south. According to this theory, they were caused by “high-powered groups” aiming to sow fear and, using the vulnerability caused, institute their own interests.

Extreme events connected to climate change are more and more frequent worldwide. In 2023, Manaus suffered from drought. Photo: Michael Dantas/AFP

Report and text: Jaqueline Sordi

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum