To understand the idea that most humans have of a delta we must go back to the letter where it all starts, which is D. The fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, which goes by the name of Delta and which Herodotus thought of when he contemplated the arched triangle formed by the mouth of the Nile. In addition to thinking it, he wrote down the shape, D, and unwittingly bequeathed the image and the name to posterity.

Delta.

These days, the word is spelled the same way in many languages of the world, from Portuguese to Kurdish, Tagalog or Yoruba. A delta is a confluence so crossings and paradoxes abound. It is a place where the end (of the river) and the beginning (of the open sea, lake or lagoon) converge in plethoric mud, full of life that is often amphibious and capable of adapting to different situations conditions between fresh and saltwater. Dying, and being reborn. Walking. Swimming. Flying.

Nowadays, with so much talk about the need to find spaces for dialogue, deltas emerge as an ideal reality because they contain a fertile mix in their very nature. But what has been written about them? The answer is: not very much. The forest, the jungle, the mountain, even the desert or, in some cultures, the sea, fill thousands of pages, but the deltas, those intermediate spaces made up of wetlands, marshes and enormous bodies of water, have little LiterNature about them, despite the biodiversity and mystery that define them.

Bearing in mind that more deltas means (much) more life, let us turn to the delta that gave its name to the rest, the Nile. Among the fields of corn, rice and cotton, the following stands out: Out of Egypt, the memoirs in which the Egyptian André Aciman —author of the acclaimed novel Call Me by Your Name — describes his life in Alexandria which was once an orchard and which is today home to approximately 2,200 inhabitants per square kilometer. The urban centres zigzag between greenhouses and petrochemical factories that partially block the river from flowing into the sea, although there are also crops and some wild corners from where cobras or Nile monitor lizards still peek out.

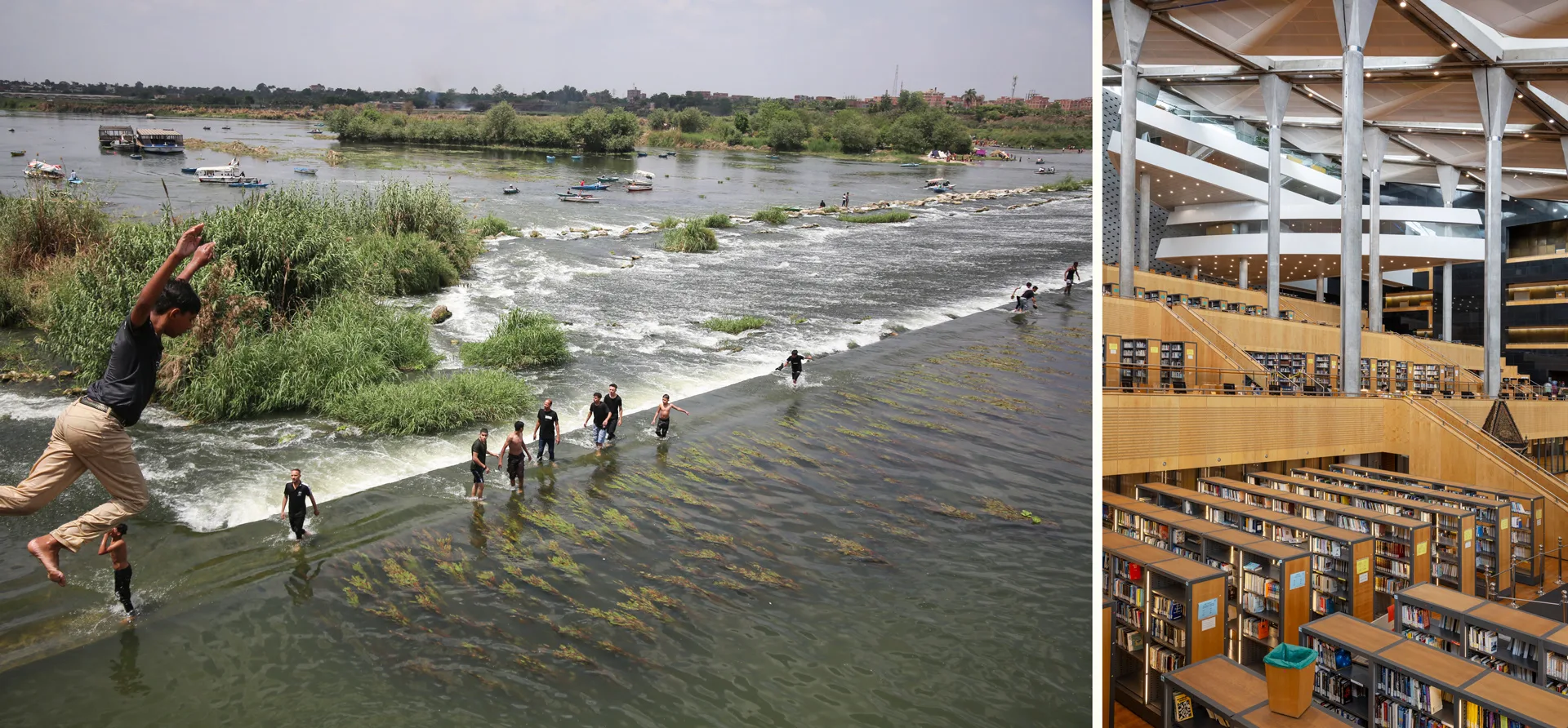

Aciman’s is a vision of another century, as romantic as those of E. M. Forster, Lawrence Durrell, or the Greek Constantine Cavafis. And, also like that of those foreigners, it is marked by cosmopolitanism and culture. Aciman belongs to a family of Sephardic Jews with Turkish and Italian roots in which Greek, Arabic, Ladino and French, a lot of French, are also spoken. He himself grew up believing he was French. But in 1965, the Acimans were expelled from Egypt, as were the French and the British, the latter after the Suez Canal conflict in 1956. The family’s story sums up the cultural crossroads of this delta, which was also marked by the earthquake and tsunami that devastated the mythical Library of Alexandria in 365.

In 2002 the new Bibliotheca Alexandrina was inaugurated. Its shelves hold many volumes of literature that tells fascinating stories of individuals, but little that gives a starring role to non-human natures. As if the original delta considered that the river, the sea, the land or the Ibisare were not “culture”. Food for thought.

People swimming in the Nile, the ‘original delta:’ the Library of Alexandria overflows with human stories, but finding Nature as a protagonist is harder. Photos: Mahmoud Elkhwas/Nur Photo via AFP and Manuel Cohen/AFP

On the opposite shore of the Mediterranean, the Danube River ends and forms what biologist and ecologist Ramon Folch claims to be the largest delta in Europe, in his book El vicio de mirar (Planeta). Claudio Magris penned a masterpiece, Danube, where philosophy combines with various species of sturgeon, including Beluga, and with gypsies and fishermen who take their children to school by boat. Guided by the monograph on the Danube written by Alexander F. Heksch in 1881, Magris conveys the physical experience of navigating a space where “there is no clear distinction between land and water,” while wondering about endings. Where does the Danube end? The answer is that in this endless ending, there is no end. So the best thing to do is to forget about vain questions and let it die in peace.

This is becoming increasingly difficult in the Mediterranean, where several coasts are facing a dizzying recession due to climate change and the arrival of a new phenomenon: the cyclone. To wait for one, I settled for a year in the last house before the sea on the island of Buda, in the Ebro delta, the first that is expected to be flooded by salt water in the coming years. After the experience, I wrote Delta, which includes The Great Conversation that takes place there, from the Flamingos to the Horses, the rice farmers, fishermen, hunters, ecologists, and ornithologists…

During the cold seasons, I would settle daily on a dune to observe the transformation of the lagoons and the beach. In the heat, I swam at the mouth of the river in increasingly less turbid waters, due to the lack of sediment retained by the reservoirs and canals —the Ebro is the second most intervened river in the world, according to scientists working in the region. Plovers, Audouin’s gulls, dragonflies, bulrushes, bulls, eels or invasive red and blue crabs are some of the protagonists of a story in which, “thanks” to the damage caused by Storm Gloria, people of very different sensibilities began a dialog to agree on ways to act in the face of the new coastal crises.

Buda Island, a place of dialogue: the time Gabi Martínez spent living on the Ebro River delta resulted in a book that brings together a ‘big conversation’ among its inhabitants. Photos: Personal archive

The truth is that, of the approximately 11,000 planetary river deltas studied by the journal Nature, only 9% are regressing. In fact, more rivers are expanding: 12%. However, this is due to the historic deforestation that is taking place in countries such as China and Brazil, which has turned the Amazon, the Huang He and the Mekong into emblems of senseless logging. Tons of discarded vegetation, branches and wood are dumped into waterways and washed into deltas that widen and grow due to these deposits.

Many of the retreating deltas are those with the highest flows, and with them, magnificent wetlands are vanishing. The Earth’s wetlands are disappearing at three times the rate of forests. Half of the world’s wetlands have vanished over the course of a century, while administrations are almost limited to contemplating the decline as if they were oblivious to the fact that these areas are capable of storing 50 times more CO2 than tropical rainforests, a fundamental value in combating the climate crisis.

Sometimes they succumb to flooding, although there are also many areas wiped out by industrial complexes. Elizabeth Rush addresses both casuistries in Rising the Pulitzer Prize finalist book that took her to the most threatened coasts of the United States. After pointing out that 40% of the world’s population lives in coastal areas, Rush details the benefits of mangroves, highlights the marshes as excellent greenhouse gas sequestrators or points out that, of the 400 endangered species in her country, more than half depend on wetlands.

In the Mississippi, the problem of chemical spills is added to that of the vertiginous regression, combated by dredges that relentlessly dig to move tons of sand to prevent the flooding of the Louisiana coastline, one of the most threatened in the world. The case of Edgard, Louisiana, in the parish of St John the Baptist, is exemplary. In a region located on what is practically quicksand, most of the town’s inhabitants are considering emigrating after learning that the companies extracting methane, oil and salt have eroded the already ultra-fragile subsoil into a polluted gruyere, a place where the risk of dying from cancer is 800 times higher than the U.S. national average.

For this reason, Rush presents examples of organized neighbors who defend their community: if it is necessary to move to another enclave, it will be to a place not too far away, maintaining more or less the landscape of their life, and all the neighbors together. For Rush, “learning to retreat together” is key at this critical time when New York, the city made possible by filling in and hardening 90% of wetlands, has announced a wall at least 7 kilometers in length to try to defend Manhattan from the onslaught of the sea.

In her book The Sea Around Us, Rachel Carson (1907-1964) explains that the Algonquians of the Maliseet tribe call the Saint John, the river that experiences the most intense tides on the planet, Wolastoq. Wolastoq means “beautiful and bountiful river”. A reflection of the calm with which the Maliseet assume the will of the natural forces that flood with clockwork accuracy the surroundings of the Bay of Fundy. What the Maliseet did not accept so well was that the construction of two large dams would decrease the migration of Atlantic salmon. Ecotourism, recreational boating and potato farming are now the source of income there.

Asian competitiveness

A traditional Hindu tale says that every 4 billion years, a flood sweeps the Earth. At the moment, the Ganges delta is one of the fastest coastal floods on the planet, comparable to that of the Mississippi. Bangladesh is ground zero for crop failures and the expulsion of people who have become climate refugees. Drama underlined by the waters poisoned by the corpses and garbage thrown into the river by the Hindus. In The Ganges Delta and Its People, David Cumming explored the solutions the inhabitants have been finding to overcome cyclones, tides and droughts by relocating crops and mangrove dwellings inland, in the domain of man-eating tigers. And in To the Mouths of the Ganges, Frederic C. Thomas also makes a cultural immersion that exposes the damage caused by shrimp fishing while highlighting how needs have prompted close collaboration between Hindus and Muslims.

The Ganges, the world’s biggest: ‘It is difficult to find a large Asian delta with a literature that is alert to its natural majesty.’ Photo: Martin Bertrand/AFP

In any case, it is difficult to find a large Asian delta with a literature that is alert to its natural majesty. In China, competition between cities has led to the Huang He River delta —where precisely 4,000 years ago Chinese civilization was founded and where the basis of the Yijing, or Book of Changes was gestated— being squeezed out as a productive area devoted to refineries and the production of steel, oil… and some peaches. The extractivist urge has also seeped into the fishermen, who have exterminated the fishery in the neighboring Bohai Sea. The result: the mouth of the HuangHe, symbol of hydraulic despotism, has as little LiterNature as fish, despite the unique narrative possibilities of its mobile delta, which over the years has been moving its mouth for miles and miles, causing the literary effect of “abandoned deltas”.

To the south, the Yangtze and Pearl River deltas form superlative concentrations of humans, in which the rest of Nature, again, seems to have no place. The Yangtze spills over several provinces, although Shanghai stands out as its most renowned deathbed. Shanghai means “above the sea”, a deception, because the city actually grows “above” the river. That mistake sums up the disconnect between the people there and their natural delta. A distance that is sublimated in the Pearl River, which has a mega-urbanization around it, the buildings seeming to emerge from the waters. Money is the objective. Hong Kong is a finance capital, Shenzhen has even created a special economic zone to facilitate piecework income, and in territories such as gambling-mad Macau, giant pipes and shovels can be seen dumping sand on the coast to build new casinos and hotels. It is estimated that, soon, some cities joined to others will add up to 120 million people in the Greater Bay Area, designed to diminish the referential power of Hong Kong, which will be economically diluted among the metropolises that have always been Chinese. The question is: how many of those people write about the water that they are surrounded by, bathe in, and even drink? There are some political, economic and social essays, but… what about the geology of the islands? What about the Daurian redstart, the Tailless whip scorpion, or the giant golden orb weaver spider? Analysts often say that these cities are megalopolises in which the agricultural and economic component has erased the geographic or biological , and the stories are built from this ultra-human point of view that has turned this river delta into one of the most polluted in the world.

On the side of the most fertile deltas, the alluvial marshes where the deltas of the Tigris and Euphrates converge have a formidable book by Wilfred Thesiger, The Marsh Arabs. The Abyssinian-born Briton lived for seven years with the aquatic civilization of marsh dwellers known as the Madan, fishing and sailing with them, among buffalo grazing on islets. The fusion of people with the environment translates into the Madan ‘s own names: Janaish (little donkey), Chilaib (little dog), Bakur (sow), Khanzir (pig), Kausaj (shark), Dhauba (hyena)… It is an absorbing book in which one learns how to make rafts with cattails, how to get rid of flies or how to fish using stramonium mixed with flour pellets and chicken manure.

And this spectacle is an incitement to miss a volume that intimately reflects the natures of the Okavango, one of the most unique deltas: because it is inland and home to one of the largest populations of endangered savannah elephants and the only swimming lions on Earth. In The Lost World of the Kalahari the controversial Lauren van der Post devoted an entire chapter to the Okavango Delta. The Bushmen, the thread that winds through the book, thought that Van der Post was in search of the ghost tree in the swamp, because it was unusual for a traveler to go into the delta when it was so hot. In any case, he was warned that crocodiles and hippopotamuses, tired of being hunted, had multiplied their attacks on humans; and that the whirlpools followed one after the other. In his adventurous way, the South African author narrates how reaching the water soothed his senses after weeks of dust and desert, and offers a sensual foray into the wild Okavango, full of papyrus, giant herons, lilies or translucent insects amidst gentle silver-colored waters.

Inner nature: writer and adventurer Laurens van der Post (1906-1996) wrote an entire chapter on the Okavango Delta, which lies entirely inland. Photo: Markus Mauthe/Greenpeace

In the Tigre

Among all the deltas, the Paraná delta is one of the most literary on the planet, where dissidents, bandits, bohemians, intellectuals and millionaires have been taking refuge from nearby Buenos Aires for decades. And the Tigre is the delta within that delta, a biosphere reserve with more than 350 rivers and streams. This is the setting for Southeaster (translated by Jon Lindsay Miles), the novel starring Boga, the lonely fisherman who builds a small boat and accepts the infrequent company of an affectionate, dim-witted neighbor and his dog. Boga internalizes the cadence of the delta merging with the landscape until the appearance of a fugitive that changes the atmosphere.

Over the years it has become known that the Boga really existed, maybe he was even called that, and that Haroldo Conti simply breathed another life into him by using his knowledge of the delta, where he had settled in 1949. The Argentine writer rented a cabin on the Gambados creek and began to travel the rivers of the region. He became a member of a rowing club. In 1954, he bought the cabin and a boat that he prepared to name after his daughter, Alejandra.

Rodolfo Walsh was a good friend of Conti, and they sometimes met at the cabin. Walsh also explored and wrote about the delta and bordering waterways, noting that mosquitoes bit him in the Tigre, Corrientes and Mercedes, but not in Iberá. From him we know that the Palometa, the red-bellied Piranha with dismembering abilities like that of the Blue Crab, can attack you if you stand still, although it refrains if it senses movement. And he met Bernardino Díaz, a gaucho who made beds from reeds, was guided by the shadow of sticks and the stars and, when he got lost, he stopped, forgot, and by erasing what had confused him from his mind, managed to reorient himself. Bernardino showed that it pays to stop and trust to walk in the right direction.

Intuition matters. “There seems to be a way,” Rodolfo Walsh noted, and, despite the dictatorship, despite the abysmal risks that threatened his life, intuition told him that the way was to write about the “rapacious illiterates” busy “amassing land, wealth and parochial aristocracy.” The military disappeared him. But today Walsh is Walsh.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento was the first to write about this Tigre delta, and he also had a house there, like Manuel Mújica Laínez, Juan Carlos Moretti or Leopoldo Lugones, who committed suicide with whiskey and cyanide at the El Tropezón inn, very close to the water he had described as “lion-colored”. Roberto Arlt’s ashes were thrown into the river that pays homage, precisely, to Sarmiento.

But, in addition to the tragic ending and their relationship with the delta, there is one point on which these real or fictional writers and characters coincide with others from various countries, and that is how much the river influences them. “They don’t love the river exactly, but they can’t live without it,” Conti summarized.

In the end, it is poetic vibration that links these works, which are capable of capturing like few others the tension between the land, the water, the sun and the beings breathed by the deltas. Capable of expressing the potential of intersection and hybridity. At a time when crossroads are multiplying, deltas are emerging as a source of solutions, places where we can learn ways of living together. Why not write about them more?

In the Mediterranean, coastal areas have retreated sharply because of climate change. Buda Island, on the Ebro Delta, will be the first engulfed by salty waters in the coming years. Photo: Personal archive

Gabi Martínez has written about deserts, rivers, seas, mountains, deltas and all kinds of living beings. He spent a year living with shepherds in Spain’s wooded pasturelands, and another on the island of Buda, in the last house before the sea, which will be the first to be engulfed by the waters in the coming years. After these experiences he wrote Un cambio de verdad [A True Change] and Delta. He has written 16 books and his work has been translated into ten languages. He is the driving force behind the Liternatura project, a founding member of the Caravana Negra and Lagarta Fernández Associations; of the Urban and Territorial Ecology Foundation; and co-director of the Animales Invisibles [Invisible Animals] project. In SUMAÚMA he writes for the LiterNatura space.

Report and Text: Gabi Martínez

Editing: Viviane Zandonadi

With the collaboration of: Meritxell Almarza (Spanish)

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Portuguese translation: Paulo Migliacci

English translation: Charlotte Coombe

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum