In the fight for the Amazon, no support for Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in these elections is more important than that of Marina Silva. If Lula can claim in debates that his government significantly reduced the deforestation of the largest tropical forest on the planet, it is because this black, indigenous Brazilian, the daughter of rubber tappers, born and raised in the state of Acre in the Amazon rainforest, was his Minister of the Environment from 2003 to 2008. But with a development-based agenda dictating the political decisions and pace of the following years, Silva left both the Ministry and the Workers’ Party. After that, the Workers Party had much less to be proud when it came to the environment. That Marina has put aside political disagreements to form part of Lula’s broad alliance, is a deeply significant event for those who understand what is at stake in this election: more than the destiny of democracy, the future of life on this planet.

Marina Silva arrived for the interview at her office in the Pinheiros neighborhood of São Paulo dressed in the colors of a tree. Her style is impeccable but understated, almost austere. She arrived as a federal deputy elected by the state of São Paulo, with 237,526 votes. Her slight figure, a voice that seems to have something painful scraping the vocal cords, and the tight bun of her hair, suggest frailty. The strength of thought and the determination that made her journey one of the most extraordinary in Brazilian politics only emerges when she speaks. Working as a maid after she left the forest and moved to the city to seek health care, Marina only learned to read at the age of 16. Taking the sophisticated knowledge of the indigenous and riverine peoples of Acre as her starting point, she embarked upon a personal journey through the great European thinkers. And also through psychoanalysis, the field of investigation of the unconscious that can be glimpsed throughout her answers in this interview. In the current Brazilian climate, Marina is possibly the political intellectual – or the intellectual politician – with the most complex way of thinking in Brazil. But, as a black woman from the Amazon, she pays a high price for such daring.

In a country undergoing religious transfiguration, Marina is also the most significant left-aligned politician who is also an evangelical Christian – and one of the few who does not use her beliefs for electoral manipulation. As a teenager she wanted to be a nun, that grassroots ecclesial community, linked to the left-leaning aspects of the Catholic Church, something which had a strong influence on her political development. Then, like many Brazilians, she found more spiritual meaning in the evangelical faith. In the recent past, a significant part of the left found it difficult to understand the strength of what Marina represented or could represent. On the one hand, her evangelical faith was one of the reasons why parts of the progressive camp rejected her. On the other, a number of neo-Pentecostal evangelicals from the flocks of the great market pastors still consider her “not evangelical enough” compared to the messianic histrionics of figures such as Damares Alves.

Her body corroded by malaria, leishmaniasis and mercury contamination, violated like the forest she has emerged from, the woman in front of the SUMAÚMA journalists is an amalgam of what is most new in Brazil: the hegemony of nature in the geopolitical recentralization of the world, the growing role of black women in a patriarchal and structurally racist nation, and the accelerated growth of the evangelical faith in a country that was dominated until this century by Catholicism. But when she won just 1% of the votes in the 2018 presidential election, Marina Silva was considered finished.

Nothing further from reality for someone from the Amazon who knows the end of the world is the middle. Marina demonstrates her continued relevance and power in this interview in which, for almost two hours, she didn’t fail to answer a single question. And some of them were pretty tough. There were some emotional moments, and Marina cried at least once, but mostly she showed why the most important political and survival act of our lives today is to vote for Lula – and to convince the undecided to vote for him.

MARINA SILVA AND LULA IN SEPTEMBER 2022, DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN, AFTER 14 YEARS OF POLITICAL SEPARATION. PHOTO: RICARDO STUCKERT/PUBLICITY

Why did you decide to realign yourself with Lula (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, former Brazilian president, and challenger to Jair Bolsonaro in this year’s presidential election) and the Workers’ Party after their disrespectful treatment towards you in previous presidential campaigns?

It was a political and policy-based rapprochement. A lot of people wondered what my position would be in these elections, and I must say I’ve been working hard right from the start… dialoguing with [defeated presidential candidate] Ciro Gomes, [and with parties like] Citizenship, Network, and the Green Party, in a serious attempt to offer an alternative to polarization. But it didn’t really work. We’re always criticizing denialists, but we have to be careful not to fall into the same trap. Reality tells us we haven’t yet achieved the change needed to break up polarization. We can’t be denialists when Bolsonaro and Bolsonarism are taking great strides towards the destruction of our democracy, which could occur on two levels. It could be an abrupt democratic rupture, something he’s constantly threatening, by trying to insert the Armed Forces into the political scenario. Or it could be an endogenous corrosion, changing the configuration of the Supreme Court, making this change, for which there is already a majority in Congress, even more profound, and through this apparatus of armed individuals, a mixture of police, militia and society. It’s a very serious threat. God help the Brazilian people if he wins this election. I’ve always said that I would be open to dialogue, as long as it was on a political and policy basis. While at the same time refuting this sexist element to the political divergence that existed, and still exists in many ways, between myself, the Workers’ Party, and Lula himself.

Sexist in what way?

I left the Workers’ Party and ran for the presidency three times, presenting a manifesto. I helped create a political party (the Sustainability Network). It wasn’t a simplistic issue, or a question of sexism, or to do with being hurt or grudges, as a lot of people like to suggest is the case with women. If it’s a dialogue with [Geraldo] Alckmin, it’s [seen as] “overcoming political differences”. If it’s dialogue with another interlocutor, [it must be] breaking through barriers, even over policy or ideology, in order to build something greater. When it comes to a black woman from a humble background, an environmentalist, the approach is always “Oh, you’ve got to leave this hurt, this grudge, behind”. At the right time, and in the right way, this meeting became possible. At the invitation of Lula himself.

What was the dialogue with Lula like?

A two-hour face to face conversation, and a political event, publicly adopting a set of proposals together with Brazilian society. All I can say is that it was such a good conversation that it produced a public discussion, resulting in the making of public commitments to a socio-environmental agenda. It wasn’t an accident that I named it “Salvaging a Lost Socio-Environmental Agenda”. There is an agenda that works, which managed to reduce deforestation by 83% [from 2004 to 2012, after which it increased again], and which created 80% of the world’s new areas of protection between 2003 and 2008 – while Bolsonaro has already been responsible for a third of the destroyed virgin forests around the world. A plan that prevented the release of five billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, the largest contribution ever made by a single country in terms of actions to combat climate change. There is no one better than former president Lula to carry out this rescue. Because all this happened under his government.

What is the strategy to actually make this happen, since in the second-round run-off Lula has formed alliances with a number of predators of the Amazon and other biomes? To what extent have you discussed whether you will have a more active role in his government, for example in the Ministry of the Environment.

Absolutely nothing has been said about roles. It was a personal conversation between two people who hadn’t talked about politics for 14 years, but who have never lost their personal bond. We’ve known each other for almost 30 years, and we met when I was still very young, when I wasn’t even part of the Workers’ Party yet. But I helped create the Workers’ Party and we have never lost that bond. It reemerged in important moments in our lives, like the death of my father, the death of [Lula’s wife] Dona Marisa, his cancer, and when I went to visit him. The social bond established between us has a base that cannot be broken, at least when it comes to extreme issues. I think that’s what ensured that this political dialogue, so important for this dramatic moment in the social, environmental, and civilizing life of Brazil, could happen.

STREAM CLOSE TO DEMINI VILLAGE, IN YANOMAMI INDIGENOUS TERRITORY, IN AMAZONAS STATE. PHOTO: PABLO ALBARENGA/SUMAÚMA

You also represent a significant portion of Brazilians who find it difficult to support Lula because of what happened in the environmental field after your departure. How did you reconcile yourself to this? Why should people believe this manifesto promise, which was broken before, will be respected this time?

Politics is a living process that cannot be repeated. A large part of the problems we are experiencing has to do with politics [being treated] as mere repetition, which always leads to stagnation. I’ve made this move because of a certainty that the worst imaginable will occur if Bolsonaro is elected. Our democracy still has many weaknesses. But it also has strengths. The “muscles” of our institutions, which have already been put under great strain for four years, might not be strong enough to withstand another four years of Bolsonaro. It’s a risk we cannot take. From one perspective, I have the element of hope and belief. Hanna Arendt said that, when faced with the unpredictable, there is only one remedy: the value of a promise. And a promise that wasn’t just made to a person, but to a people. I feel that Lula is at peace with this reunion. I feel at peace. [But] there will be disputes, of course. It is certainly a broad alliance, but it is an alliance between those who want to mediate pro-sustainability. Whether they’re socialist or capitalist, conservative or progressive. Before we were the outsiders.

Have things really changed?

The problem of climate change, the loss of biodiversity, everything that’s happening in the world, is now imposed by science, reason, common sense, ethics and even aesthetics. And it requires everyone to be sustainable. It is no longer a question of development, but of sustainability, [although] some will be conservative, others progressive. Only the deniers will not be in favor of sustainability. They are the ones willing to destroy the planet.

CRIMINALLY SET FIRES IN AMAZON RAINFOREST, NEAR PORTO VELHO, IN RONDONIA STATE. PHOTO: BRUNO ROCHA/FOTOARENA/FOLHAPRESS

And why is that?

It’s because there is a fundamentalist vision behind all of this, the idea that whenever there is terrible chaos, a great catastrophe or a flood, there will be a renewal of humanity, a revival. That’s their logic. Even conservatives have to understand that if the Earth’s temperature continues to increase, there will be no Amazon, no water, and no agriculture. The market doesn’t care whether or not indigenous culture is preserved, or whether or not the problems of inequality, racism, or homophobia, are solved. But it will be worried about nature.

You claim there is a consensus, even among conservatives, on sustainability. There is, however, criticism of sustainable development. Ailton Krenak [an indigenous Brazilian intellectual] has said that sustainable development is personal vanity. It won’t be possible to be sustainable within a completely unsustainable system…

I think we operate on a number of levels. It’s how we communicate with seven billion people. And it’s already difficult to communicate at this frequency of sustainable development, which, with great difficulty, has become a material concern for many people. Now, just because there’s a frequency at which you are understood doesn’t mean you have to give up your soul. So then there’s another frequency. If you don’t maintain principles of responsible living, which provide support so that we can reinvent ourselves in a relationship with ourselves, with nature and with others, then it’s an empty concept. Sustainability is not a way of doing. It has to be a way of being. It’s not just a technical form. It has to be a vision of the world, an ideal of life, based on identifying ideals. Until 400 years ago, it was the identifying ideal of how to be. The Romans wanted to be great and strong. The Greeks wanted to be wise and free. The Egyptians, immortal. In the Middle Ages, people wanted to be saints. And they believed that if they were something, they deserved to have. If I’m wise, I’m free, I deserve to go down in history. This is what has brought us here, with all the problems of what we are. Mercantilism began 450 years ago, and everything changed. Now, if I have, I deserve to be. If I have money, a car, a house, I deserve to be happy. But our ability to desire is infinite, and we have seven billion people desiring to have, and we can no longer sustain it. So, dialoguing here with Ailton Krenak, we require a shift. There are limits to everyone having car, to everyone eating meat. But there is no limit to writing the best journalism, or writing the best poetry, or composing the best music. I’m disputing things to the limit. I’m disputing gold, land, meat. In the intensive limits, I’m disputing skills. That’s how we’ll survive on this finite planet.

Bolsonaro received 51 million votes in the first round of the elections, and an even more anti-environmental Congress was elected. What form will the battle take, if Lula wins, or if Bolsonaro wins? What will it be like to deal with someone like [Bolsonaro’s former environment minister] Ricardo Salles, for example?

We’re going through a serious regression. It’s a regression to an earlier point in civilization. If before people wanted a father and a mother, we have regressed to the idea of having a messiah. It is the height of regression to a childish, powerless, fearful, terrified view of the world. This is very dangerous, because those who are terrified, [who are afraid] to face the world, are capable of destroying the very world that terrifies them. That’s what Trumpism does, and that’s what Bolsonarism wants to do here in Brazil. That’s where my reasoning comes from: it’s not about being optimistic, but being insistent. A psychoanalyst friend has a phrase that caught my attention: wherever you go, be. Whatever exists, let’s push for it. If we have the root of something that can reduce deforestation, let’s push for it. We have to make the transition to low carbon agriculture. We have to go to the financial sector, which can’t simply talk about ESG [Environmental, Social, and Governance] values, then lend to those who are going to destroy the forest, or who do not respect indigenous lands. The barriers are going up. Carbon-intensive products are going to be tariffed, they’re going to be taxed, the European Union is putting up barriers, the US [too]. China won’t be left out. When that happens, won’t we have to play our part?

And if we don’t?

There are those who’ve always acted from the heart, and those who act from reason. Those who act neither from reason nor the heart have to face legal restrictions. One of the proposals [concerns the] 57 million hectares of public land that are currently unallocated. What we call “landowner regularization” means gifting [these areas] to land grabbers. These 57 million hectares have to be assigned to conservation units, or for the demarcation of indigenous lands. Not for clearcutting [deforestation].

Recent deforestation in the Apuí region, in the south of Amazonas state. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/ Folhapress

You mentioned the infantilization of politics, of the shift from the vision of a mother and father, to one of a messiah. Is this a reference to Lula’s paternal style of government, and how Dilma [Rousseff, Brazilian president prior to Lula] was described as the “mother of the PAC” [Growth Acceleration Program, using the Portuguese acronym, as Brazil’s growth stimulus plan at the time was known]?

I’m not coming up with names. I’m thinking of the political imaginary of the people, this political ethos that exists in Brazil. Let’s take Getúlio Vargas, who was a great father figure in history. People often say to me “You’re the mother of environmentalism”. And I say, “No. This fight is ours, forget the idea of having a mother, [because] it’s a childish way of thinking. But at least this idea still lay in the human or the cultural realm. This regression goes back further than the father and mother. It’s the idea of a messiah, a savior of Brazil. It’s something much deeper and obviously much more dangerous. Because you’re removing the transforming power of politics, aren’t you? People don’t see themselves in the role of the protagonist of their lives, their stories. And it’s also connected to the idea that charismatic figures are strong in Latin America. I say this putting myself in a similar context. I’m a charismatic person and I know how powerful that is. If there’s one thing I want to use charisma for, it’s to convince people that they don’t depend on it, that [on the contrary, they need to] take responsibility. This is difficult, or painful, it isn’t something we want. We want someone who fights for us, who speaks for us. Taking responsibility is painful, and operating in politics with this concept is an unknown territory. If we look at [history], the dispute used to be whether Brazil was a metropolis or a colony. Then we got our independence. Now, are we a republic or an empire? We can be a republic. Is it agriculture or just extractivism? Agriculture or is it industry? Democracy or dictatorship? If you always polarize, you’ll always have disputes. But the polarization has also been regressing, and has come down to individuals. The political and economic model is left behind and turns into polarization between parties. And then it becomes polarization between people. Now, we’re at the level where we’re polarizing between God and the Devil.

How do you confront this?

When we go to the limits of this nonsense [Marina uses the word in English for emphasis], something has to emerge from it, some meaning, some resignifying. This movement today is to defend a fundamental idea, which is at both the base and the surface level of sustenance for everyone. It’s different from when you’re in a situation of democratic normalcy. You have a people who are choosing something very important to them. We are electing democracy, but it can’t be untethered democracy, it has to have a program of policies. Not [the program] of a single party or a group, but a mosaic of ideas. That’s why there is a place for our proposals, and for those of Senator Simone Tebet [defeated presidential candidate for the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party], and for those of Ciro [Gomes, defeated presidential candidate for the Democratic Labor Party]. It’s the chance to keep fighting for what we believe in, because with Bolsonaro that chance is diminished.

What would you do in the event that Bolsonaro wins a second term?

A second term for Bolsonaro is unthinkable. Because it would put the Amazon at the highest possible risk and place indigenous populations at the highest level of vulnerability. But it’s something unthinkable that has to be thought about. And if we can’t think, we have to act. At this moment, that means acting by voting for a victory for Brazil. We cannot reduce what we’re doing to simply defeating Bolsonaro, just as we cannot reduce it to merely a victory for Lula. What we’re doing is making Brazil victorious. When [Fernando] Haddad and Bolsonaro emerged on the scene [in the 2018 election], there was no need to even have a debate about policies. I knew what Bolsonaro signified. Just as I now know what’s at stake for democracy, for social policies, for human rights, for the Amazon. Back then, I said: “Bolsonaro will cross the limits of what western democracy means”. And he did. Now, he wants to cross the limits from within, changing the Supreme Court, impeaching ministers, with a style of usurpation parliamentarism, with a secret budget in which to put money. Then you’ll become a Honduras, a Nicaragua, a right-wing Venezuela.

Do you think that today there’s a critical mass that represents society and is less linked to paternalism?

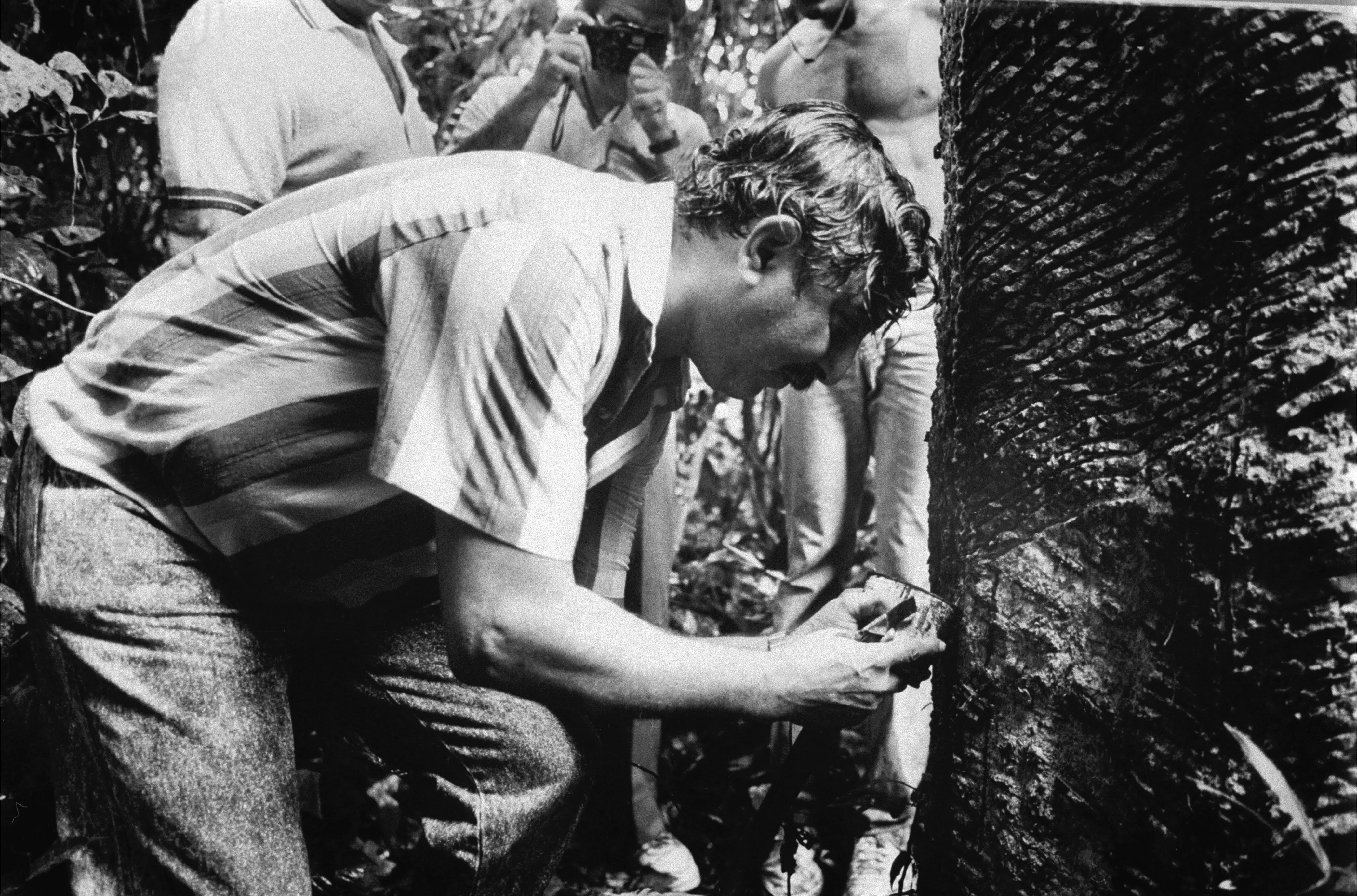

Yes, and this becomes part of the public imagination. A large number of Brazil’s solutions were produced by society. This is our basis for hope, this is what we will push for. It’s wherever you go, be. The SUS (Brazil’s national public health service) comes from health workers, from doctors committed to public health. Where does the idea of social policies to help the poor and the vulnerable come from? From the battles fought by Betinho, by Dom Mauro Morelli. And it gained strength through science, from the social perspective of economists, from Ricardo Paes de Barros, Maria Peliano, or Cristovam Buarque. Where does the idea that the Amazon should be protected come from? From Chico Mendes, from the Aliança dos Povos da Floresta (the Alliance of the Forest Peoples, a social and political organization). Who helped to systematize this? Mary Allegretti, Mauro Almeida, Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, Steve Schwartzman. Where does the potent strength of the black population, of young people or women on the outskirts of our cities, come from? It comes from this ability to perceive oneself as a protagonist. I get emotional when I speak. We have a childish side, but we are growing into adulthood. And it is by becoming more adult that we will hold on.

LULA, ELECTED IN DECEMBER 2002, AND MARINA SILVA, WHO WOULD BECOME HIS ENVIRONMENT MINISTER FROM 2003 TO 2008. PHOTO: ROBERTO CASTRO/ESTADÃO CONTENT

It can’t be denied that your work in the Department of the Environment was extremely important, and much of what the Workers’ Party reaps today in the environmental area has its roots in that period, and came apart after your departure. But you also authorized the first large-scale hydroelectric plant in the Amazon, Jirau and Santo Antônio, on the Madeira River, in Rondônia, which was a watershed moment. It didn’t happen quickly, but you approved the first major hydroelectric plant in the forest since the dictatorship. That was disastrous. What do you say to people in the Amazon, who today suffer from the impact of hydroelectric plants? Belo Monte became better known because it was more widely covered, but Jirau and Santo Antônio had, and is having, an absolutely devastating impact.

Look, when I started at the Ministry, there were 45 hydroelectric plants that were, let’s say, paralyzed. Some we allowed to happen, taking all the necessary care required, but we were brave enough to say no to some, something that had never happened at the Ministry of the Environment. We said no to the Poeiras hydroelectric plant, which people sometimes forget. We said no to the Tijuco Alto hydroelectric plant, which would flood quilombo (communities originally formed by escaped slaves) land here in São Paulo. That was Antônio Ermírio de Moraes’ project, and no government had had the courage to say no, but we did. We said no to the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant and referred it for further studies. All this had a major political impact. The Santo Antônio and Jirau hydroelectric plant had a strict schedule for the approval of its license, and we took every measure necessary to reduce impacts. The license was granted with 42 conditions. Unfortunately, I left the Ministry soon after, and these conditions weren’t followed. It was supposed to have three dams. We reduced it to one. It was supposed to have two locks, but they were denied. Why did it need locks? It would have destroyed the forest so soy could be planted. We granted a license that moved worlds, and funds, to minimize environmental impacts. There would be an impact, but it would certainly not be the impacts that were proposed. So I’m responsible for the project as it was licensed and not for what it became. It’s clear to me that every effort was made for the project to be carried out correctly, under pressure from within the government, and the media, and the business class and the state of Rondônia… We did what the technical advisors believed. And in my government, it wasn’t a political license, it was a technical license. And precisely because it is a technical license, you won’t find a representative of Ibama (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources) saying the Minister pushed for the license to be granted. It was the same with the São Francisco River, where the license was granted with extreme caution. The proposal was to extract 126 cubic meters of water per second. We reduced that to 46 cubic meters per second. People have no idea how big these changes are, and how hard it is to face all the questions. All the legal challenges at the Public Prosecutor’s Office failed because the license was so consistent. It was granted with a program to revitalize the São Francisco River. Unfortunately, everything that was needed for this revitalization to take place was abandoned after my departure. I can’t be held responsible for what I sadly couldn’t continue. But maybe that’s why I left, because I could only stay if I was able to do things as they should be done.

The Santo Antônio hydroelectric plant is located on the Madeira River, in Porto Velho, State of Rondonia

You are the most important evangelical politician aligned to the left or center-left in Brazil. Although evangelical is not a generic term this group, for the most part, supports Bolsonaro. You have more difficulty dialoguing with evangelicals than pastors like [Silas] Malafaia and other politicians who represent “market evangelism”. Why?

You stated initially that evangelical is not a homogeneous condition. There are numerous denominations, and even among those with a prevalence of mostly conservative views, there are people who do not necessarily agree with these reactionary and sometimes fundamentalist positions. I am an Evangelical Christian of the Assembly of God. There’s no point in them saying I’m not a true evangelical, because that’s not for us to judge, it’s up to God, alone and exclusively. And I don’t call them false believers either. I can only turn to the teachings of the faith I profess, which is Jesus. He said “You know a tree by its fruit.” I don’t see good fruit in a tree that wants to arm an entire population. I don’t see good fruit where there’s indifference to suffering or death, or gloating over the grief and pain of nearly 700,000 people who have lost their loved ones. What did Jesus do when Lazarus died? He went to Maria and Martha’s house, and wept, though he knew he was going to resurrect Lazarus. But death is something so profound, so terrible, that he wept. A God in the form of man weeps in the face of death and goes to visit two sisters, in a society that didn’t value women… who when they lose their brother, become nothing. They didn’t have a husband, or anyone to protect them. I can’t, when looking at this fruit of a Jesus who respects and shows solidarity with women, see the fruit of disrespect for women. I cannot see a comparison between the fruit of Jesus and a fruit that demonstrates prejudice, against anyone, based on their color, ethnicity or sexual orientation. I can’t see how as a good fruit someone would want to impose their faith, when The Bible itself says: “it is not by might nor by power, but by my spirit”.

But why, even with this rotten fruit, do the polls show that the majority of evangelicals vote for Bolsonaro?

We need to think about the prejudice the evangelical has towards the non-evangelical, and that which the non-evangelical has towards the evangelical. We need to learn to talk to this other. The sacred has a place in the psyche, in human transcendence. [Even if] others don’t embrace this idea of the sacred, it imposes itself in a certain way, through art, or philosophy. Learning to talk to this other may become a learning experience we’ll go through from now on. In [the elections in] 2010 and 2014, a large number of those who voted for Bolsonaro voted for me. And I didn’t make the churches an election platform, or my election platform a pulpit. Nor did I suddenly go along with the expectation that some had of me, in taking on a reactionary conservative and fundamentalist agenda. The demand for political participation from a segment of the population that numbers much more than 40 or 50 million, which can be as many as 70 or 80 million people, is legitimate. They are citizens. Just as it’s legitimate for others not to have their political participation vetoed.

What made this population group change their vote?

I think at that time [when the demand for political participation became clear], we could have done something really positive with this strength within a democratic context, and it would have honored our legacy of the secular state, which is a contribution of the Protestant Reformation. It is a contradiction for evangelicals to hold this view because it was the Protestant Reformation that decisively helped to bring about the separation of church and state. [The secular state] is a way of not excluding people, including allowing those who made up the great religious diasporas, to have the freedom to be able to exercise their faith without being persecuted or thrown into the fire. Brazilian society gave three major signs that it wanted changes in the area of democracy, that it was already experiencing a great deal of fatigue with the Workers’ Party vs Brazilian Social Democracy Party polarization. [French thinker] Edgar Morin said that, in the beginning, change is just a small deviation, and we have to be attentive to which deviation we will encourage to prosper, and which we don’t want to prosper.

And what were these three signals for Brazilian society?

In 2010, Guilherme [Leal, Brazilian entrepreneur and one of the owners of the Natura cosmetics group] launched a candidacy based around sustainability. We got nineteen million six hundred thousand votes. In 2014, I had 26% of voting intentions, which put me in first place, and beating all the candidates in the second round. Rede [Network, the party she created] wasn’t officially registered because of political maneuvering. So I supported Eduardo Campos [Brazilian Socialist Party candidate for whom Marina Silva became a running mate], then the tragedy [Campos’ death in a plane crash] occurred and I received 38% of voting intentions. [Between these two campaigns] there were the 2013 protests, which weren’t led by a particular figure or an institutional political process, but rather society, positioning itself as an actor in the political scene, saying “we want change”. There were three big signs. It’s as if there was something repressed, something very bad, down there. And that was the first sign. Nobody cared. A second sign. Nobody cared. A third… nobody cared. Only the last layer remained. And then came the worst of Brazilian repression. The slavocratic, patriarchal root, the vision, the reactionary root. And in 2018, what happened happened. Most of us underestimated Bolsonaro. But we can’t underestimate him twice. If we are not wise enough to learn from our mistakes, of not having properly read Brazilian society, we don’t have the right to fail to learn from Bolsonaro’s election in 2018. We don’t have the right to be stupid.

Lula is part of this whole journey. After 14 years when you didn’t speak to him so much, which Lula did you find?

Look… it would be arrogant of me, from two hours of conversation, to give this kind of reading. But what I can tell you is what I feel, and not just about Lula as an individual. When you’re a political figure with a very strong gravitational pull, even your individual changes will be in some kind of context. Being the person who has the best and biggest chance to help defeat Bolsonaro is very important, it transforms a person. I feel like he’s making a number of adjustments, and I hope they take hold. We have adjustments that need mediation, because we deal with and manage many interests. It is legitimate for people to want land to plant crops in, but our constitution and science are telling us we can’t keep destroying the Amazon. We cannot accept someone seeking to bypass this interest in the preservation of life. As [singer and songwriter] Gilberto Gil says: “the people know what they want, but they also want what they don’t know”. And what the people want and don’t know is something the politicians have to pay for. When I ran a department, when I was a senator, I was unable to walk around half of my state, Acre, for four years. If I did, I would have been lynched, because of the road I said couldn’t be built without an environmental impact study, without demarcating indigenous land. So, what happened? Once, because they said I was on a plane that was going to arrive in Cruzeiro do Sul, people set tires on fire, put tractors on the runway. The plane couldn’t land. A girl was almost lynched because her name was Marina. Radio Verdes Florestas, which was the Catholic radio station, had a presenter named Brás. He called me, in Brasília, so that I could speak live on the phone, giving my version of the story. The bishop had to intervene, because they wanted to lynch Brás. When I talk about this I want to cry [her voice breaks]. This collective madness of destruction, of the death drive, has been active for a long time. It’s what killed Chico Mendes, what killed Sister Dorothy [Stang]. I get upset, I’m sorry.

THE RUBBER TAPPER, LABOR LEADER AND ENVIRONMENTALIST CHICO MENDES, MURDERED IN 1988 FOR HIS DEFENSE OF THE FOREST, COLLECTS RUBBER IN THE XAPURI REGION, IN ACRE STATE. PHOTO: HOMERO SÉRGIO/FOLHAPRESS

Working in the Amazon for so many years, it’s clear there is no other politician in Brazil, with your stature, your support and your experience, of rubber, the riverside, the forest peoples. At the same time, it seems to me that your support base among riverine and indigenous populations, among agroecological workers, among forest peoples has been weakened, or in some cases ruptured. They seem to identify with you less than might be expected. Does this make sense to you, and if so, why might it have happened?

I don’t think electoral density is an indication of either a bond or a rupture. For me, my support base and my relationship with the people of the forest are organic. But I don’t necessarily have the objective conditions to translate this into votes. Just as the support base of Soninha (Guajajara) among the indigenous people is organic, and undoubtedly true. But unfortunately the reality we face, and the disputes that are created, don’t allow this to happen. I was a councilor, a congresswoman, twice a senator in Acre, working for Brazil and for the world, and I didn’t worry about maintaining electoral bases. I worried about using the opportunity I had, to do everything I could [becomes animated], in the morning, in the afternoon, at night. To reduce deforestation in the Amazon, double extractive reserves, prohibit 35,000 land grab [theft of public lands] properties, apply R$4 billion in fines, put 725 people in jail, create 25 million hectares of conservation areas, oversee the first ever institutional dispute with 480 federal police officers in the state of Mato Grosso. And to remain there for five years, five months and 13 days, only visiting my state, where my support base was, at Christmas, to see my family. This isn’t a rupture, it’s a commitment [Marina’s voice breaks]. Between preserving my electoral base and doing what had to be done, I decided to do what had to be done, because that’s what I learned from Chico Mendes, who was never elected either. We really wanted him to be elected to Congress, but the people didn’t like him. Just as the press didn’t cover him [weeps]… And we survived. And sometimes we have to leave our family, we have to leave our relatives, to do what has to be done. It’s deeply painful, but sometimes it has to be done. Soninha [Guajajara] could have been elected in the state of Maranhão, but it was São Paulo that elected her. I had two terms in Acre, working for Brazil, to achieve these results. In the fight I’m in, I could be a candidate for any state. But I feel my foundations are organically preserved, in the work that has been done both in the legislature and in the ministry. At the end of a mandate, it’s very difficult for someone who has turned down the pension of a retired senator, who has a small party without party funding, to be present, like the major parties are. I know people miss me. They wish I was there, but I work. I am an associate professor at the Dom Cabral Foundation, I have to give lectures to survive, to pay my rent.

As one of the missions of SUMAÚMA is to valorize the intellectuals of the forest and of nature, it’s notable that although you have mentioned respected European intellectuals, you haven’t said anything about the intellectuals of the forest. Can you tell us something about that?

With respect to authors, I’d say you’re right. It’s just that when something feels so organic within you, sometimes you don’t mention it, which is unfair, because I feel entirely connected to Ailton Krenak. I feel him, and it’s like he’s already here. It’s like he’s here [points to her body]. So, I talk about what is on the outside [becomes emotional]. And I try to express what is inside. But you’ve made me think. Maybe I have to name what’s inside. And the name of what’s inside is Ailton Krenak, is Davi Yanomami, is Joênia Wapichana, is Soninha Guajajara, is Chico Mendes, is … my grandfather, my rubber tapper father, is Dona Raimunda, a coconut harvester. And I can name them, yes [her voice lifts], and from now on I will name them. But this is here within me. Maybe in the same way that Ailton [Krenak] doesn’t need to talk about Marina. And I notice that he doesn’t say much either, because it’s already inside him. We formed the Alliance of the Forest Peoples. I was very young and so was he, but he was a little more mature than I was. We were all there. And perhaps I, as a political figure who has to speak to many people, so that all this can be expressed in a vote, have to say this, because Edgar Morin was very important in my life. The idea of complex thinking was that it gave a place to everything I got from my uncle, or my midwife grandmother, or from Ailton Krenak, in this literate world, which does not understand narrative knowledge, because it only dialogues with the postulates of denotative knowledge, of right and wrong. I apologize for getting emotional, because unfortunately we live in the world, and I, who was almost a nun and a Catholic, and today am an evangelical Christian, our civilizing ethos comes from a sacrificial culture. And I remember people accusing me: “you don’t visit your electoral base, you won’t get reelected”. And so I said “I won’t be a candidate anymore”. And I only came back because I thought it was the only thing I could do right now. At 64, having been a candidate since 1986, when I left for the first time to try to get elected as a member of the National Constituent Assembly, to put forward everything I believed was better for the Amazon, for indigenous peoples. I got the fifth most votes, but I wasn’t elected. This time, with my grandson, I thought, “I’m not going to be a candidate anymore. I’ll continue to help in my own way. By trying to write my book, which I never find the time for.” But, in self-defense of democracy, of the Amazon, of indigenous peoples, even those who think I’m not there anymore, it is in their name that I left [to become a candidate] again.

This slavocratic root, which you hinted at, competes with another type of root, the one you brought from Ailton Krenak, from your midwife grandmother, from the forest people. Will we be able to water this root, to strengthen it, and make it win out for once and for all?

Look, I don’t even know if it’s a case of winning out… how do we process this, this slavocratic pain, it’s here, it’s a scar. But it needs to heal. We don’t need to erase the scar, it’s here to stay. A scar is like a belly button, you know? It’s there to show us that we needed a placenta. But it has to be re-signified. And perhaps where this is most difficult is in relation to black people themselves, to indigenous people. In some ways I’m both. I’m a black woman, a woman with indigenous blood, but also with Portuguese blood. And for a long time people said to me: “but aren’t you part of the movimento negro (Afro-Brazilian identity and civil rights movement)?” Today I’m more at ease with this. There’s been a change. “Because you only talk about the environment…” But I’m a black woman, who was born in the Amazon rainforest, who learned everything from the indigenous people, from the mysteries to the beauties of the forest, with my uncle who, when he was 12 years old, went to live with the indigenous people of the Upper Madeira River. And he is a very important person in my life. With him, I learned to make crafts, to do a little bit of many things. It couldn’t have been different. But I don’t think a black person isn’t an environmentalist because they don’t do what I do. Just as no one should think I’m not a black person because I have an environmental agenda. It’s good we’re now tackling all the categories of environmental racism. It has a lot to do with this, and perhaps I always put myself in that situation. There are moments when you’re a bow. There are others when you’re an arrow. And you have to intersperse these positions. The things that I do, that Ailton Krenak does, that Davi Yanomami does, that other people do, for me they’re neither complementary nor exclusive, they’re supplementary. And each does as much as it can. When they’re supplementary, they are two different realities, which interrogate each other, which talk to each other, even if they end up deepening their differences and each goes off in their own direction. People are supplementary. The negationist logic of Bolsonarism, however, is excluding and exclusivist. It wants to eliminate, it wants for us not to exist. And then there can be no dialogue.

Translated by James Young