On a Sunday in August 2023, seven months after the administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party) declared a public health emergency, medical personnel in the Awaris region of Yanomami Indigenous Territory saw an exhausted, famished man emerge from a trail in the woods, carrying several straw baskets his community had made to offer in exchange for food. He had spent the whole day walking through the forest in search of help. His people were sick and dying. And they were hungry. Very hungry.

In his village of Koraimatiu, and in at least three other villages nearby, dozens of children, young people, adults, and the elderly were suffering from malaria, fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and, among the women, bleeding, the man said. There were no doctors or nurses stationed in the vicinity, nor a radio they could use to call for help. So, weak as he was, the man had made his way through the forest in hopes that the rescue team’s helicopter would be available. Every second without help could cost a life. The man had the resigned look of someone who had made this pilgrimage numerous times before, and on every occasion had heard excuses. A lot of excuses.

That afternoon, he dictated to healthcare workers a list of 13 of his people who had died in the previous two months, including both adults and children, in the villages of Momoipu (4), Silipi (6), and Katanã (3). The next morning, he headed back home. “When I woke up, he had left,” said one of the professionals, who became visibly emotional when recalling the case he had witnessed. “All he had were his handicrafts. I’m sure someone gave him something, a couple of kilos of rice, and he left with two kilos of rice, and hunger.” It would be weeks before the helicopter got there.

The situation in the Awaris region is among the most serious in the territory. That was where some of the photographs that moved the country in January 2023 were taken, when SUMAÚMA reported that 570 Yanomami children under the age of five had died due to a lack of basic health care during the four years that far-right President Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) was in office. After the story was published, the then new president Luís Inácio Lula da Silva declared a public health emergency in Yanomami Indigenous Territory. Since then, the Workers’ Party administration has invested more than $200 million in emergency initiatives and nearly $45 million to restructure healthcare access for the Yanomami—122% more than the previous administration, according to the Health Ministry. It has also mobilized almost 2,000 healthcare professionals and increased the number of doctors stationed in the area from nine to 28, through the federal government’s More Doctors program.

In January 2023, photos published by SUMAÚMA of malnourished and sick Yanomamis shocked the world; the Lula administration declared an emergency

Something, however, hasn’t worked out as it should have. This is what can be gleaned both from the testimony of people in the area who were heard by SUMAÚMA and from statistics for the first eleven months of 2023. In the first year of Lula’s administration and of his declaration of a public health emergency, 308 Yanomami died from January through November—104 of them under the age of one. This figure approaches the 343 deaths recorded for all of 2022, the last year of Bolsonaro’s administration.

Indicators released by the government show improvement in some of the health statistics in the territory, reflecting the resumption of services that had been shut down due to illegal mining operations in the area. However, they also show that the explosion of malaria cases was not contained this first year. According to the Health Ministry’s agency for epidemiological surveillance, SIVEP-Malaria, by the end of November there had been 26,641 cases in the region, where just over 31,000 Indigenous people live. This represents a 70% increase over the 15,665 cases reported for the whole of 2022 as well as a rise over 2020, when 21,983 cases were reported, the highest figure since at least 2014.

The government claims this higher number stems from greater testing, since its strategy has been to actively search for cases, unlike the previous administration. But data obtained by SUMAÚMA under the Access to Information Law show that while the 2020 malaria spike killed three Yanomami children under the age of five, there were 15 fatalities in this age bracket in 2023—five times as many. In 2022, five children died.

Malaria is a disease spread by the bite of mosquitoes that proliferate in standing water, like the ponds left by illegal mining operations. It is a highly incapacitating disease that requires a long course of medication and thus a qualified medical team to follow patients closely throughout treatment. Moreover, the illness can exacerbate other health problems. When the human body is run down, other illnesses, such as viruses that cause flu or diarrhea, can turn deadly fast, requiring immediate care.

By early October 2023, 9,550 cases of acute diarrheal diseases had been reported in the territory, surpassing the figure of 5,902 for the entire previous year. Cases of flu-like illnesses skyrocketed from 3,203 in 2022 to 20,524 during the same period of 2023. According to data obtained under the Access to Information Law, in the first 11 months of the Lula administration, 14 children under the age of five died from malnutrition (9 in 2022), 30 from pneumonia (56 in 2022), and nine from diarrhea (17 in 2022). While underreporting that occurred during the Bolsonaro administration precludes a more accurate comparison of figures for 2022 and 2023, it is undeniable that, given the huge investments made in the first year of the Lula administration, better indicators were expected.

There is no doubt the Lula administration has invested in resources and staff, demonstrating a political will to respond to the Yanomami genocide. So what happened? SUMAÚMA spoke to healthcare workers and Indigenous leaders from different regions of the territory to understand how the government spent $200 million and mobilized nearly 2,000 healthcare workers—and still failed. Most of those interviewed by SUMAÚMA asked not to be identified for fear they might be removed from their assignment caring for the Yanomami.

Lula and his ministers were in Boa Vista in January 2023 to declare an emergency in Yanomami territory; after all of the investments made, the situation is still severe. Photo: Ricardo Stuckert

Those who spoke to SUMAÚMA were unanimous in saying there was a management problem. And in an emergency, good management means the difference between life and death for those at risk. Good management is also what makes or breaks logistics, the core of any emergency. Interviews and data gathered by SUMAÚMA show the government did not respond adequately to an emergency situation and that a state of disaster still prevails in the territory. “It was management by amateurs. With lots of academic degrees, but little or no field experience,” said one medical worker. “It ended up being money used for pretend purposes, for the sake of appearance. Because what matters isn’t how many white coats we bring into the territory, but how many people we actually care for.”

Among reasons for this failure, healthcare workers cited the haste with which initiatives were conducted, with no coordination or knowledge of reality in the territory; little openness to adopting protocols used successfully elsewhere by NGOs with vast experience in emergency work; a lack of willingness to listen to and act in partnership with anthropologists, geographers, and other Indigenous specialists who have been working with the Yanomami for decades, as well as with the leaders of the people who have been affected; the absence of ongoing basic health care in villages; and challenges encountered in expelling illegal miners from some areas and keeping out the criminals who have already left other areas, with a clear lack of cooperation on the part of the Armed Forces.

So far, for example, the government has taken no steps to re-open the healthcare hub in Kayanau, a community that has suffered greatly from the presence of illegal mining activities and where there have been reports of sexual abuse, child prostitution, drug trafficking, and the presence of heavy weapons that present a threat to Indigenous lives and health, as SUMAÚMA revealed in a February 2023 report. Only occasional healthcare missions have been carried out there, but these were interrupted by illicit mining. The same has been true in Xitei, where criminals have prevented missions from reaching the region’s healthcare hub.

The hospital in Surucucu cares for Indigenous gunshot victims attacked inside of Indigenous territory. Photo: Antonio Alvarado/Associação Urihi Associação Yanomami/AFP

When healthcare workers asked about going into these areas, the National Public Security Force claimed they had no way of guaranteeing the teams’ safety. While the State fails to fulfill its legal obligation to make the region safe for work to resume, the Yanomami continue to die, in the shadows of the statistics because there is no one to record the deaths. Other base healthcare hubs in the territory, which had been closed during the Bolsonaro administration due to threats from criminals, were reopened between March and October. In two of these, healthcare units have been set up in makeshift huts with tarp roofs, built with the help of Indigenous people.

Information from a report produced by the Special Office of Indigenous Health this month and obtained by SUMAÚMA reveals that three of the reopened hubs are at risk of closing because of increased criminal invasions in the surrounding area. For security reasons, they are only partially open at present. In the document, the Indigenous health office requested support from the National Public Security Force.

“The situation is complicated because malaria continues. We keep losing our children. This month, two died in [the village of] Õkiola,” said Mateus Sanöma, a leader from the Awaris region. Mateus pointed out that the greatest number of deaths and cases of disease have occurred in communities where there are neither health posts nor airstrips, so the only way to get there is by helicopter, a chronic structural challenge the government has yet to solve. “Our children still have diarrhea. The worms are getting worse too. It’s a lot to worry about. My people are still suffering there.”

Leaders from more central areas of the territory also report the situation in their communities is dire. “Things still haven’t gotten better. We still have the diseases—malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia. Many have started dying again. My family, my Yanomami people, are dying to this day. I’m very angry. Lula said he was going to improve our health care, but he hasn’t yet. Many things are needed,” said a Yanomami leader from the community of Papiu. “Illegal mining continues, the river is polluted again, lots of xawara [diseases and epidemics]. Malaria, diarrhea, vomiting, worms,” said Fernando Palimi Thëri, another leader, from Palimiu.

Illegal mining and clandestine airstrips remain in some areas of Yanomami territory. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

Malaria also contributes to food insecurity. By making the body weaker, it prevents the Yanomami from planting crops at the right time or going out hunting. Parents become so debilitated that they are unable to eat or feed their children. After the task force was set up, the government began using aircraft to drop packages of food staples to the villages in an attempt to ameliorate food insecurity. But the strategy did not guarantee distribution to the neediest within each community, according to two medical workers. “I saw packages arrive in a community and then stay there, near the healthcare post. Anyone who was farther away didn’t get one,” one of them explained.

Distribution was also hampered by the Armed Forces’ inefficiency, deliberate or not. The Brazilian military, which claims to have delivered 36,600 food packages during this period—averaging out to fewer than two units for each of the territory’s 31,000 inhabitants for the entire year—failed to provide all the flight hours that Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs Funai needed to distribute purchased foodstuff, hindering delivery to villages. “The government sent in the food packages but then stopped two months back. Our gardens are still small. The malnutrition continues,” said Mateus Sanöma. While Indigenous people are starving in the forest, TV Globo’s Fantástico news program is reporting that there are now 28,000 packages of food staples waiting for distribution in Boa Vista, capital of Roraima, the state where much of Yanomami Indigenous Territory is located.

The same strategy of dropping parcels of food from the sky—which means they often burst open on impact—has been adopted in a number of areas in the territory, including more structured places, like the Surucucu healthcare hub, which became a showcase for government work because it is home to a reference hospital. The airstrip in Surucucu was practically destroyed in January 2023, preventing the landing of the Army’s larger types of aircraft, such as the C-195 Amazonas, which can haul food parcels. The Army was supposed to renovate the runway and, in February of last year, Indigenous Peoples Minister Sonia Guajajara said there was a commitment to beginning the work. One year later, the airstrip has undergone some repairs but still cannot handle larger planes.

Airstrips were not fixed and large Army aircraft loaded with food cargo were unable to land. When dropped from the air, food packages burst open. Photos: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil and Wanderson Gontijo/SVSA/MS

Things started out badly—and continued… badly

“Like drying ice,” a Portuguese expression for describing an exercise in futility, was used by more than one medical professional to define the work carried out under the command of the Yanomami Center for Emergency Health Operations—the brains of the initiative in Yanomami territory. One of these professionals, who has decades of experience in emergency care, was horrified when he attended an internal meeting one month after the center opened and saw the tremendous disorganization. They hadn’t even mapped out the specific emergency situation to be addressed, something that must be done within 72 hours in these situations. “It was like everybody was a beginner, but with exaggerated self-esteem,” the healthcare worker said. “There was no scientific grounding, no grounding in practice, in everyday life. That, to me, is serious. How do I think this could have been solved? By putting in people with field experience, emergency experience. Not experience one or two times, but many times. And these people exist. They exist—but they were sidelined. Everyone who voiced warnings about the mistakes being made, who went head-to-head, was sidelined,” he said.

The Center for Emergency Health Operations operates out of a room in Boa Vista, where it coordinates care for the territory. Photos: Health Ministry and Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil

The lead decision-maker at the Center for Emergency Health Operations up until July of last year was Ana Lúcia Pontes, an exemplary academic from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), a center of excellence in research with a long record of service to the public in the area of health. Although Ana Lúcia’s doctorate is on Indigenous health policy and she is part of the “The Health, Epidemiology, and Anthropology of Indigenous Peoples” research group, her critics allege she has no consolidated experience in either direct care to Indigenous populations or emergency situations.

“Generally, in an urgent or emergency situation, the decision-maker is the person with the most experience in the field. But this wasn’t the case of the coordination at the Center for Emergency Health Operations,” said another healthcare worker. “So a very serious mistake began right there: choosing a researcher or someone from academia for a decision-making spot during an urgent situation. Why is this serious? Because you have very little time. If you really want to save people and make a difference, you have to know how to coordinate logistics, which forms the core of humanitarian structures. They are the person who will decide which profile is best suited to this type of disaster, and other posts will be defined from there,” the professional said. “But instead of choosing a logistics specialist, an administrator, people with experience in disasters or public health emergencies, they chose other researchers. It was management by amateurs, but amateurs with a lot of academic titles, who refused to be challenged.”

When contacted by SUMAÚMA, Ana Lúcia Pontes said she has worked with Indigenous communities since the beginning of her career and was the go-to person at Fiocruz when it came to Indigenous health during the COVID-19 pandemic. She also worked on the construction and design of the emergency plan for the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib). “I began [heading up the Center for Emergency Health Operations] because I’ve been a technical reference for Apib in recent years. And I was called in because of this trust on the part of Indigenous movements,” she said. “Who would be the ideal person? There is no such person, with all the necessary experience. What we did was bring together technical areas within the Health Ministry and institutions such as Fiocruz and PAHO [Pan-American Health Organization] that had diverse experience with public health emergencies.”

Ana Lúcia said that from the very beginning the emergency operations center included people who worked in the field with the type of care needed for illnesses such as malaria. She mentioned the physician Marcos Antonio Pellegrini, who worked in the Surucucu region in the 1980s and 1990s. Pellegrini is now in charge of the Special Indigenous Public Health District in Yanomami territory. Ana Lúcia, who headed the center from January to July of 2023, also said that from the outset she called all the organizations working in the region, as well as Indigenous leaders, to invite them to take part. She argued that the solution to the situation will involve tackling the systemic problems of a health system that has lacked a solid structure for years.

According to those heard by SUMAÚMA, however, a failure to assess the situation properly or rely on professionals familiar with emergency work and with the Indigenous territory resulted in erroneous decisions that ignored the specificities of the Yanomami context, which requires complex cultural, social, public health, and geographical knowledge. “An emergency is made up of details. And that’s why only specialists are sent in during an emergency because you have to understand a given subject very well to be fast and precise. You have to be very surgical in what you do. When someone doesn’t have experience with emergencies, they’ll apply the routine metrics they use in their own life. That doesn’t work in an emergency. That’s why their biggest initial mistake was sending people who had only worked in routine situations to a public health emergency. They continued using a routine approach to the work,” the professional argued. “Without [an efficient] Center for Emergency Health Operations, there was no point sending in hundreds of thousands of personnel, because that’s just drying ice.”

In early February, volunteer healthcare providers from around the country, working for the public health care system’s National Force, were sent to Yanomami territory. After arriving in Boa Vista, they stayed in lodgings where there were several beds in one room and then sent to the Indigenous area, having been tested for COVID-19 but not quarantined. They were dispatched to different regions of the territory, where they ran the risk of testing positive in the field and spreading COVID-19 to an already debilitated population. A number of them tested positive when they returned from the territory, suggesting that contamination may have occurred. In addition, healthcare workers heard by SUMAÚMA said many of these volunteers had no experience whatsoever in necessary areas of care. Nor did they understand the Yanomami’s reality. They had spent one to two days at most receiving instructions. Their participation lasted about two weeks, counted from when they left their points of origin until their return home. Flights were sometimes delayed, and some groups spent only a week in the field.

Some healthcare workers were assigned to areas where no prior security assessment had been done. “We worked under a lot of pressure. Everyone was upset,” said one professional who was sent to a healthcare hub early on. In some cases, the coordinating team gave out incorrect information, saying there was malaria in a given place where there wasn’t, or vice versa. Relying on this initial information, the agents went into the field without enough tests or medication to combat the disease where necessary or they returned from places where there was no malaria with leftover medication and tests.

The life and death of a hospital

“We’ve known about this crisis for nearly two years,” said Dr. Ricardo Affonso Ferreira, the president and founder of Expedicionários da Saúde, an NGO. The straight-talking physician manages an institution that set up a field hospital for six months following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, it took part in specialized training on catastrophes in Geneva and Oslo, it assembled 260 field infirmaries in Indigenous communities during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it has carried out countless surgical missions in Indigenous areas in Brazil. While there was criminal inaction from the Bolsonaro administration in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, Expedicionários da Saúde carried out three expeditions to the area in 2022 and employed an almost guerilla-type scheme to try to save the lives the government was ignoring.

Expedicionários da Saúde, an NGO, renovated care facilities in Surucucu. A four-wheeler was used to carry patients to the airstrip. Photos: Marcelo Moraes and Expedicionários da Saúde archive image

“We sent infectologists and pediatricians to take care of everything that was happening, the hunger, the malaria, because the previous Special Indigenous Public Health District administration was very problematic,” he recalls. In order to make sure the medications the institution had purchased reached the villages where they were needed and did not get lost in bureaucratic wrangling in Boa Vista, the Expedicionários da Saúde would deliver them directly to the doctors going to the communities. “We started to put together special rescue backpacks and would give them to the area’s workers,” said Marcia Abdala, the institution’s general director. The organization also distributed generators and solar panels, in addition to taking doctors from village to village to provide care. In this moment of crisis, the organization was one of the few providing effective aid to the Yanomami, who were facing an acute lack of care.

It was therefore no surprise when the Center for Emergency Health Operations came to the NGO shortly after the task force began to be implemented, so that the employees recently dispatched by the Lula administration could understand what working in the territory entailed. Expedicionários da Saúde offered to set up an emergency center in Surucucu, to work as it had elsewhere, using experience gathered over the years. “But our offer was rejected,” said Ricardo. “We had a surgery center; we were used to working in the area. We did our first surgical expedition to Surucucu ten years ago. We knew the entire region, the leaders,” Marcia said.

According to them, the Center for Emergency Health Operations said this was because it would be a government initiative and the Armed Forces would assemble one field hospital in Surucucu and another inside of the Indigenous Health Support House. This unit is a support facility in Boa Vista where the Yanomami are taken to finish recovering after they leave the hospital in the capital. Or rather, that is how it works in theory.

In practice, they often wind up staying months after being discharged because there are no flights back to their villages. During this long wait, they end up catching other diseases or even become victims of sexual violence in the case of the women. President Lula went there in January 2023 for a visit. He left horrified by the overcrowding: it held 700 Indigenous people, in a space made for half as many. Today, there are even more people than this space could hold with any dignity.

Yet fifteen days went by before anyone contacted Expedicionários da Saúde again. With only the Indigenous Health Support House field hospital up and running, the government was now asking for help. On February 12, 2023, the Expedicionários da Saúde logistics team was in Surucucu to check out the facilities at an infirmary that they had themselves refurbished ten years prior, with the support of Indigenous affairs agency Funai. “We arrived and there was no water, sewerage, housing, kitchen, or bathroom. The patient area was disgusting, it was completely abandoned, destroyed,” they recall. Without the minimum to maintain any type of team, it would be impossible to set up the hospital. So Expedicionários da Saúde began remodeling the structure. “In the beginning we asked the Army, the Air Force for support, because we had to bring in materials, rocks, cement, timber. But we didn’t get it. The only help we got, right at the start, was from the team at the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics, who were doing the Census. They would squeeze us in on flights when there was space, until the Center for Emergency Health Operations organized things to charter a plane and help us bring the rest of the material there, some forty-five days later,” said Marcia.

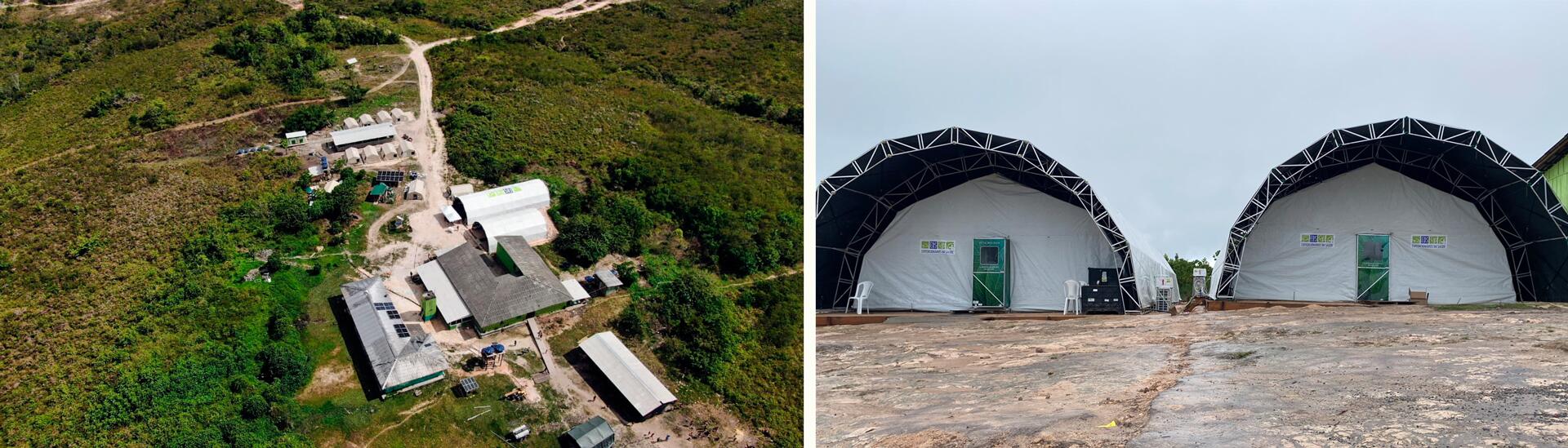

By late March, the hub area was suitable for operations. This made it possible to set up tents near another structure that then functioned as a hospital, offering outpatient care, an emergency room, and a laboratory, with the government calling it an Indigenous Health Reference Center. Patients from the surrounding villages who needed to be hospitalized were now taken here instead, without having to be evacuated to hospitals in Boa Vista, which also helped reduce the flow of sick Yanomami who ended up at the Indigenous Health Support House.

These tarp structures served as hospitals in Surucucu, but they were decommissioned as hospitals after Expedicionários da Saúde left. Photos: Expedicionários da Saúde archive image and Marcelo Moraes

“So we began to bring our health teams to Surucucu: pediatricians, clinicians, infectologists, everything we felt was necessary to care for these more serious emergencies. But then everything was a mess,” said Marcia. “There wasn’t any coordinator who would receive all of these workers and say: you go to the communities; you others stay here. The work had to have a direction,” said the head of the Expedicionários da Saúde NGO. “It had to be like a hospital: first do triage, exams, isolate people who might have tuberculosis, COVID-19, put a wristband on them. And this was not done,” she points out. One day, a patient with flu-like symptoms was placed in the same area as a group of other sick and debilitated people, without a COVID test being done. This patient was positive and infected the other sick people, the doctors say.

Another mistake was that there was no systematic work being done inside of the villages during this time when care was provided, the doctors point out. “What needed to be done was to go into the communities, bring the team to see the malaria situation there, treat the malaria there. Yet this rarely happened. It was all about drying ice,” Ricardo said. “We wanted to go, but they said that only the Special Indigenous Public Health District team could enter,” he said.

In June, the hub’s coordinator told them Surucucu didn’t need medical specialists, like the pediatricians and infectologists they had brought in. Rather, they needed emergency medical technicians. “So there was nothing else for us to do there. We were all specialists. We left,” recalls the Expedicionários da Saúde director. The NGO withdrew its doctors from the territory but left the field hospital. A maintenance team and a lab technician also stayed on until the end of August. They said the government later stopped performing maintenance and the structure began to deteriorate, turning into a hazard, prompting them to remove it.

In late October, the Indigenous Health Reference Center, proudly opened by the federal government at the start of the year, closed its doors. It has yet to be replaced. The patient flow at the Indigenous Health Support House has once again increased, reports one healthcare worker who was there in the second half of 2023.

Skin over bones

The images that shocked Brazil in January of last year put a face to an extremely acute nutritional health situation. Data sent to SUMAÚMA at the start of that year by the Lula administration’s own Health Ministry show that in 2022, out of the 4,367 children under the age of five who were monitored by healthcare teams in the territory, half were underweight—of these, 1,239 were severely malnourished. SUMAÚMA requested the latest data from the Health Ministry’s press office but was not sent this information. The last bulletin released by the Center for Emergency Health Operations says that 416 children have been treated for malnutrition and discharged so far. Fifty-six of them are currently being monitored and thirty-four are severely malnourished.

Without data, there can be no real comparative analysis on how the malnutrition situation has evolved during the task force’s first year. However, images published by the G1 website last week show children who are still skin and bones being rescued by healthcare teams at the Awaris hub. Three of the healthcare workers SUMAÚMA spoke to for this report said the strategy used by the government to fight malnutrition could have also delayed the recovery of the youngest Yanomamis, again due to an initial lack of familiarity with the local culture.

Images obtained from the G1 website show how malnourishment, made worse by illness and the lack of a medical team, continues to devastate regions like Awaris. Photos: screenshot/Fantástico/TV Globo

In February, the Health Ministry began distributing therapeutic milk to children, which consists of powdered milk, oil, sugar, and micronutrients with vitamins. It provides a fast and easy way to boost caloric intake. Some Yanomami, however, are unaccustomed to drinking any milk other than mother’s milk, and it was hard to get the Indigenous people to use it. The Center for Emergency Health Operations nutrition team then added in banana and açai, foods that are part of the local culture, to try to increase its consumption. But it was still hard to get the Yanomami to consume it, and the number of times the substance needs to be administered is a challenge, especially in the villages.

Three workers who talked to SUMAÚMA said that distribution of the milk and the government’s insistence on this strategy troubled Doctors Without Borders, which, like Expedicionários da Saúde, had been called by the Center for Emergency Health Operations to work in the territory. The NGO, which has experience helping children recover from malnutrition in acute scenarios in Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, wanted to introduce what is known as a Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF), a peanut or chickpea-based paste or solid substance that comes in package form. It might prove more popular and would be more practical to use in remote areas, particularly because it does not depend on water and so has a lower risk of contamination. Children gain weight in just a few days, said one worker who has cared for serious cases of malnutrition. The proposal has yet to leave the Health Ministry’s Office of the General Coordinator of Food and Nutrition, causing some friction.

We asked Doctors Without Borders for an interview but were informed that its spokespersons were currently unavailable due to scheduling conflicts. However, a 2006 news article published on its website talks about a successful experience with using these prepared foods in regions of Niger. “A few years ago, all severely malnourished patients were admitted to therapeutic nutrition centers. The nutritional treatment was based on a powdered therapeutic milk [different from the one used in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory] and the average time in hospital was thirty days. This system had some problems, such as higher rates of abandonment, less coverage, a need for more human resources, and a greater risk of infection from diseases associated with malnutrition,” the organization said.

According to one worker in the field who observed the care provided to those suffering from malnourishment, this scenario is being repeated in Yanomami Indigenous Territory. “Triage is done in community, malnourished children go to the healthcare post and from there they are evacuated [by plane] to the base hub, where nutritional recovery [with milk] is done. This recovery process is very questionable, lengthy, costly; it requires a lot of staff and, again, is centralized at a base hub [far from the villages and communities they come from]. This has not provided results that are actually significant,” the healthcare worker said.

According to a Doctors Without Borders news item from 2006, the use of Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food meant that most children could be treated in their own communities, with conventional medical care, minimizing hospitalizations. “This is what is used in nutritional emergencies around the world, but here in Brazil they’ve decided against it,” one worker said indignantly. A Forest Mix is currently being tested, which contains babassu, Brazil nuts, cocoa, milk, and brown sugar, with many of these ingredients coming from Indigenous and family farms.

Illegal miners checked out, but never really left

Years of deliberate abandonment by the Brazilian government during the Bolsonaro administration allowed illegal mining to sink its tentacles deeply and dangerously into the territory, with the presence of heavily armed men and members of criminal factions. This made it harder to remove the groups. Yet the new administration’s lack of an effective plan to attack the problem was also a factor in why some criminals never left the territory and, in many of the places where they did leave, began to return in the second half of the year.

A photo taken in February 2023 shows illegal miners leaving after security forces arrive. When inspections dropped off in the second half of the year, the miners returned. Photo: Lalo de Almeida/Folhapress

“The government’s plan was split into two phases. The first was geared toward evicting [expelling] illegal miners and guaranteeing they did not return to the territory,” explained federal prosecutor Alisson Marugal, who heads the office for the defense of Indigenous and minority rights, in Roraima’s capital, Boa Vista. It was his office that filed a series of requests in recent years for the Brazilian government to explain the abandonment of the territory’s Indigenous people. In the last year, he has also closely followed the Lula administration’s work. “The second phase of this project,” he adds, “started along with the first, but it would end once the illegal miners are totally removed and public safety is reestablished in the territory for public services to resume, such as health and education,” he said. “But public safety was never reestablished in the territory so as to guarantee the efficiency of the public healthcare service,” he said.

Examples given by the prosecutor include the situation at the Kayanau healthcare hub. “Kayanau, with this entire tragedy involving illegal mining, was never reopened. And now the healthcare unit there was burned down out of Indigenous anger. Kayanau continues to be a tragedy. The government says it provides care, but what it does there is emergency medical evacuation, which is the same thing the Bolsonaro government did.”

From February to December of 2023, the Federal Police system that monitors new areas of deforestation indicated these types of alerts fell by 81%. During this same period in 2022, the last year of the Bolsonaro administration, there were 2,137 of these alerts. For 2023, they totalled 400. This is a significant drop in an area where the level of deforestation had been growing. Yet data fails to register the illegal miners who go back to the same areas they had occupied before, returning to clearings they had opened and then abandoned. In these cases, there is no need to clear any new areas, which would be the type of change to the forest that would trigger the system to issue an alert. “Even if there are fewer [deforestation] alerts in the territory, the fact is that there are still some areas where illegal miners continue to operate. Either they never left, or they left and came back very quickly,” Marugal says. Reports from Indigenous leaders also indicate the illegal miners who remained began to use strategies to keep from being discovered by authorities, such as working at night or assembling structures underneath trees.

In June 2023, changes were made to the presidential decree signed by Lula in January, establishing measures to confront the fight against illegal mining in the territory. The new text authorized the Armed Forces to carry out actions to prevent and repress crimes in the territory, with patrols, body searches, searches of river vessels and aircraft, and immediate detention when a crime was being committed. “The decree gave the Armed Forces the ability to act directly in incursions against illegal mining, which wasn’t possible before, because they were limited to logistical support,” the prosecutor explained. “From then on there was a certain consensus that the Armed Forces would take over the operation. And the Federal Police and [environmental regulator] Ibama would [only] monitor actions to destroy machinery, which would be their job. But the issue is that it didn’t work, because at a certain point, around October, the Armed Forces began to disengage from the operation,” Marugal noted. He said the defense agency began removing its troops, claiming there were not enough resources. “This began to gradually create an environment that encouraged the return of illegal mining to Yanomami territory, and from then on, we also began to receive a lot of information that the illegal miners were returning to the communities.”

The Armed Forces’ entry into the operation caused Brazil’s environmental agency to transfer its resources to other regions of Brazil, the prosecutor points out. “Now, in December, is when it [Ibama] began to come back,” he said.

The Army was supposed to refurbish a landing strip in Surucucu, but it only made repairs. With this, larger airplanes are unable to land. Photo: Fernando Frazão/Agência Brasil

Lula’s response

On the eve of the one-year anniversary of the scandal that brought the Yanomami genocide to the world’s attention, pressure was building on President Lula for having lost time in the Indigenous territory. Given the unrelenting march of death there, he called together his top officials, as he had done on January 20, 2023, this time telling them to devise a more effective plan. “We’re going to decide to address the Roraima matter, the Indigenous matter, and the Yanomami matter as matters of state. We cannot possibly lose a war to illegal mining,” he said on January 9. “And this meeting now is to define once and for all what our government is going to do to prevent Brazil’s Indigenous people from continuing to be the victims of a massacre.”

The following day, January 10, government ministers returned to Yanomami Indigenous Territory to assess the situation, among them Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva, Indigenous Peoples Minister Sonia Guajajara, and Human Rights and Citizenship Minister Sílvio de Almeida. Likewise present was Joenia Wapichana, Roraima native and president of Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency Funai. Neither Nísia Trindade Lima, Health Minister, nor José Múcio, Defense Minister, were part of the delegation. Marina Silva said the government wants “transparency” and “reality”—not “self-deception.”

With deaths still high, in January of this year ministers, like Marina Silva, are returning to the territory for new announcements. Photo: Ueslei Marcelino/REUTERS

For professionals in the healthcare field, the president’s words sounded like a replay of one year ago. “It reminds me of Groundhog Day. I feel like I’m living through the same day as a year ago,” one of them said, referring to the popular movie in which Bill Murray’s character keeps waking up to relive the same day over again, until he manages to become a better person. After all, the Yanomami have always been a matter of state, according to the Constitution—and resolving the situation was the promise made in January 2023. Lula also omitted any mention of the more-than-apparent problems encountered during the public health emergency operation, effectively transferring all responsibility for its failure to the challenge of expelling the miners.

The president announced investments of $250 million in the region for 2024, along with the creation of a “Government House” that will bring together the various federal agencies involved. “We’re going to shift from a set of emergency actions to structural actions in 2024. This will include the areas of territorial control and public security,” said Rui Costa, the President’s Chief of Staff and coordinator of these initiatives, in a public statement. According to Costa, the offensive against the invaders will no longer entail specific operations, as it did last year, but will now consist of ongoing work, encompassing new surveillance structures—something specialists have been calling for since the Bolsonaro administration, including staff from Brazil’s environmental protection agency Ibama. The new plan will take responsibility for distribution logistics away from the Armed Forces starting in April.

Used to hearing promises ever since they were forced into contact with the napepë (non-Indigenous people), the Yanomami dream of leading free lives in the rainforest—free of xawara (diseases and epidemics) and of violence. This is how the situation was summed up by one Yanomami leader from the Papiu region, who goes by the pseudonym Inoque Irana, a major spokesperson of the resistance since the earliest mining invasion, in the 1990s:

“We want to go back to living by ourselves again. We don’t want the miners. Before, it was just us living here; this is our land. We don’t want them destroying our land all the time. This is the land that was put here by Omama, our creator. It wasn’t the government that created this forest-land; it wasn’t the miners who created this forest-land. They don’t have their wives and children here, or their mothers or fathers, or their parents-in-law. Just us, the Yanomami, live here.

Communities like Xaruna, in the Parima region, are among those still being severely impacted by the humanitarian crisis (2023)

“We live where the forest is whole. Why do the napepë keep coming back and making us suffer? If we just had the health [team], medicine, that would be good; if we just had the vaccines, that’s what we want. We want healthcare professionals who know how to heal us, who work with microscopes. In the past, we have disappeared. This time, we’re not going to disappear again.

“If [the miners] keep coming into the forest, our children will suffer from hunger. The forest has been taken over by machinery. The scent of the forest is gone; I can’t smell the flowers anymore. Everything smells of gasoline, and so the game has fled. Now we’re very hungry.”

For the Yanomami to go back to living “where the forest is whole,” however, the government will have to overcome not only the forces on the other side of the trenches but also the serious problems on the inside, which have cost lives that can never be recovered. This can only be done by being transparent, by facing reality—and not through self-deception.

In 2023, at least 14 Yanomami children died of malnutrition, but statistics from this time period are still incomplete. Photo: Screenshot/Fantástico/TV Globo

WHAT THE BRAZILIAN GOVERNMENT SAYS:

According to the Health Ministry, it has “resumed health and care policies following the lack of care and abandonment that caused serious damages to the Indigenous population’s health in recent years.” The ministry points out that the initiative put together by the federal government has increased healthcare staff numbers and more than doubled investments in health initiatives, while working to ensure health care and fight the most prevalent illnesses, such as malaria and malnutrition, in Yanomami territory.

“To tackle the emergency situation, complex interministerial logistical and operational initiative was assembled immediately in light of the situation in the Indigenous territory at the start of the year. Under the coordination of the Yanomami Center for Emergency Public Health Operations, nurses, pediatricians, nutritionists, emergency physicians, and clinical physicians were mobilized, along with the Unified Healthcare System’s National Force and trained professionals who are recognized by local leaders and have technical knowledge and experience in Indigenous health,” reads the ministry’s statement.

The ministry also says that the emergency operations center plays an organizational, planning, and monitoring role, in addition to engaging with other entities, such as governmental and nongovernmental organizations that were invited to contribute to federal government actions. “In relation to the partnership with NGOs and experts in the region, it is worth noting that the team at the Office of the Secretary for Indigenous Health held meetings with Doctors Without Borders, UNICEF, Expedicionários da Saúde, and Instituto Socioambiental, in addition to contracting workers involved in creating the Yanomami Public Health District. The statement from the ministry underscores that NGOs and experts were invited to join the emergency public health operations and were able to participate in meetings from the start. And that Yanomami leaders were also consulted.

The Office of the President, which is responsible for interministerial coordination, including on the Yanomami emergency, said in a statement that over $200 million has been invested in this endeavor since January 2023, including funds from the regular budget and extraordinary funding (funds not initially in the budget).

“In 2023, 122% more was invested in health than in 2022. Healthcare staffing also rose by 40%, soaring from 690 to 960 workers. One result was that 307 children diagnosed with acute or moderate malnutrition recovered during the year, and there were over 21,000 instances of medical care provided.” The office also points out that active searches were done to detect cases of malaria, with 140,042 tests performed.

Like the Health Ministry, this cabinet-level office stressed that the number of deaths in the territory is constantly being updated because death notices have to be investigated. “Therefore, considering underreporting up until 2023, this could lead to an even greater number of deaths for 2022, after data is consolidated,” according to the Office of the President.

The Indigenous Peoples Ministry said that “the crisis in Yanomami territory is complex and has grown worse in recent years, when public policies to protect Indigenous people were severely affected.” Its statement emphasized that 400 operations were carried out last year in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, apprehending over $120 million in property and financial resources from illicit groups. It went on to point out that the Federal Police implemented 13 operations during 2023, resulting in 114 search and seizure warrants and 175 arrests during the commission of a crime. “There are 387 ongoing investigations, including those focused on major sponsors of the illegal gold trade, aimed at ascertaining the criminal responsibility of the biggest financial backers [of illegal mining].”

ILLEGAL MINING

Ibama, Brazil’s environmental regulator, told SUMAÚMA that after most of the illegal miners had been removed from the Indigenous territory, the agency’s inspectors found that some groups had returned and had started operating at night and in more remote areas closer to the Venezuelan border, in an attempt to circumvent the authorities. Nevertheless, the environmental agency states that the number of new areas used for illegal mining fell by 85% between February, when the task force started, and December 2023, as compared to the same period the year before. “This drop coincides with the locations where Ibama has acted to destroy illegal miners’ equipment and camps.”

The agency notes that it blocked the flow of supplies, such as fuel, food, and spare parts for illegal mining, carrying out 310 surveillance actions that apprehended or destroyed 362 camps, 151 logistics structures and support ports, 34 aircraft, 32 barges, 43 boats, three tractors, six vehicles, and 45 chainsaws. There were also 205 surveillance actions carried out on landing strips in Indigenous territory and in the surrounding area and an additional 209 airstrips were monitored. Ibama also points out that its inspectors have been the victims of attacks by firearms inside of Indigenous territory at least twice.

When asked, the Defense Ministry did not say why the Brazilian security forces have not yet been able to fully remove these criminals from protected territory or why it has failed to act to recover the State’s health unit buildings that were shut down by illegal mining, such as the Kayanau unit.

SURVEILLANCE

In regards to the weakening of actions to combat illegal mining after President Lula issued a decree in June authorizing the Armed Forces to act to suppress crime in the territory, the Amazon Military Command responded that the decree “establishes that the Defense Ministry, through Ágata Joint Command, is responsible for executing actions to prevent and repress cross-border and environmental crimes. […] However, it is important to stress that the decree makes no explicit mention of actions to evict illegal miners.” “Nevertheless,” it continues, the Command “has carried out significant actions in the region with other government agencies, resulting in a 90% reduction in illicit flights and an 80% drop in the presence of illegal miners.”

MALNUTRITION

The Health Ministry stated that when operations began it created a Nutritional Recovery Center to treat malnourished children at the Indigenous Health Support House, in Boa Vista, bringing the number of deaths from malnutrition down from 44, in 2022, to 29, as of November 2023 (this data refers to the total population; deaths among children under five have increased, as shown by data obtained by SUMAÚMA through the Access to Information Law).

“It is worth noting that at the start of the emergency, the Health Ministry protocol for acute malnutrition recommended hospital-level care, as was necessary due to the seriousness of cases encountered. In this sense, the Health Ministry team established criteria and procedures to identify children at acute nutritional risk, implementing a treatment plan and criteria for progress based on the ministry’s guidelines. The formula provided was compatible with the Yanomami peoples’ natural diet, containing, for example, banana and açaí, unlike the formulas suggested by other institutions,” it said.

KAYANAU

Regarding the failure to open the Kayanau base hub, the Health Ministry says this was due to local illegal mining activities. The ministry says it opened seven base hubs, while three others (the Awaris, Surucucu, and Xitei hubs) are only operating partially, during daytime hours, because of the lack of healthcare worker security caused by criminal activities.

“In locations where medical workers have secure access, the emergency care and Indigenous health monitoring needed can be provided. To guarantee access to locations where there is no security, the Health Ministry continues to work in conjunction with the Public Security Forces,” the ministry notes.FOOD PACKAGES AND MILITARY SUPPORT

Through its press office, the Defense Ministry responded that “since the federal government started the task force, in January 2023, the Armed Forces’ logistical support to help the Yanomami has resulted in distribution of around 766 metric tons of transported food and materials, distributing over 36,600 food packages. Furthermore, 3,029 medical visits were carried out along with 205 medical evacuations by air.” The Defense Ministry also stated that soldiers working in operations to combat illegal mining have detained 165 suspects. “Approximately 1,400 soldiers from the Marines, Army, and Air Force were deployed. Aerial efforts totaled around 7,400 flight hours, equal to 40 trips around the Earth.”

SURUCUCU

In relation to the airstrip at the Surucucu Base Hub, which the Army was supposed to refurbish, the Amazon Military Command said that it is owned by Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, which shares responsibility for maintenance with Infraero, Brazil’s aviation authority. However, “keeping in mind the urgency of the mission to support Indigenous communities in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory,” its soldiers also worked from December 2022 to July 2023 on emergency maintenance for the runway, making it currently possible for “small and mid-sized aircraft to take off and land.” “Note that the lack of access by river or over land by road, along with the weather conditions characteristic of the Western Amazon, restricts this work substantially in terms of materials and supplies used in the operation,” the ministry concludes. It also stated that there are no records of the Expedicionários da Saúde (EDS) NGO lodging any formal request with the Brazilian Army to borrow aircraft to carry construction materials to the hospital in Surucucu.

The Indigenous Peoples Ministry stated that, along with the Indigenous affairs agency Funai, it has tapped emergency funds for a cooperation agreement with Infraero to refurbish airstrips inside of Yanomami Indigenous Territory. “The Infraero team is already starting work in Roraima. There was a slight delay in mobilizing the team, but activities are now in progress.”NEXT STEPS

The Indigenous Peoples Ministry pointed out that structural actions in the region for 2024 include around $240 million that will go to investments. There will be a “Government House” in Roraima, comprising representatives from a variety of agencies, which will carry out actions like encouraging resumption of the Indigenous way of life in order to reestablish fishing and farming, while permanently guaranteeing that food security does not depend on food packages arriving.

“In the meantime, the food package distribution program will remain active,” says the ministry. It also stressed that the House would speed up actions, including the removal of intruders from the territory, with the security forces having a permanent presence. The government also announced plans to build Brazil’s first Indigenous hospital in Boa Vista.

Reportage and text: Talita Bedinelli, Eliane Brum, and Ana Maria Machado

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreading (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Diane Whitty and Sarah J. Johnson

Photo editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (editor-in-chief)

Director: Eliane Brum