The government of right-wing extremist Jair Bolsonaro reduced health surveillance of Yanomami children when half were malnourished, according to data obtained exclusively by SUMAÚMA. The reduction left already frail children without regular access to doctors, underscoring the genocidal treatment of the ethnic group during Bolsonaro’s four years in office, when at least 570 Yanomami children died from causes that could have been prevented with proper healthcare – a 29% increase compared to the previous administration. Malnourished children are nine times more likely to die from illnesses such as pneumonia and diarrhea.

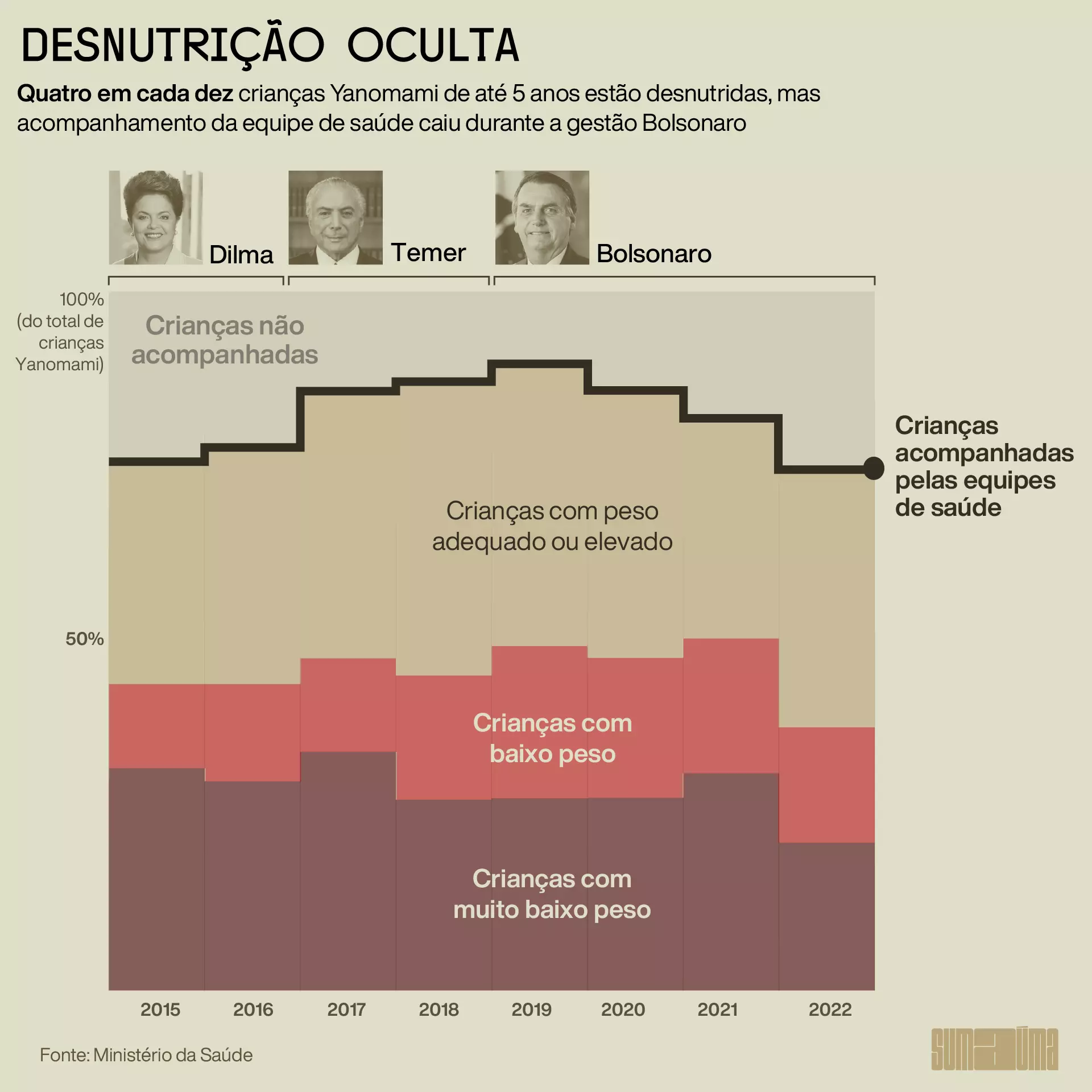

The data show that, in 2019, the first year of the Bolsonaro administration, at least 2,875 Yanomami infants aged five or under (49% of the total) were below the expected weight for their age – and of these, 1,601 were extremely underweight, the most severe category of malnutrition. In that year, 90% of children in the territory had their health monitored, and the malnutrition data were the highest detected since 2015, when the current data collection system started. Faced with this level of malnutrition, the obvious course of action would be to invest in recovery, prevention and follow-up care. Bolsonaro’s government did the opposite. In the following year, the number of Yanomami children who had their health monitored began to decline, reversing the trend of previous years. In 2022, Bolsonaro’s last year in office, the proportion of infants who had their health monitored fell to 75%. As a result, the rate of malnourishment – at least according to the statistics – also dropped, with 38% of the 5,861 Yanomami infants classed as underweight. This is what is known as a “statistical blackout”. With reduced health surveillance, the numbers appear to “improve”.

Between the first and last year of Bolsonaro’s government, at least 876 fewer children were regularly monitored. In 2022, 2,205 of the 5,861 Yanomami infants were underweight, with 1,239 far below their ideal weight. However, due to a lack of surveillance, the government is unaware of the nutritional status of 1,494 children. It is during health surveillance that children are weighed, measured and have their general medical condition assessed. It allows malnutrition to be identified at the outset, so that medical professionals can take immediate measures to reverse the situation. Without this, children can become severely malnourished, and have to be taken urgently, by plane, from the Yanomami territory to Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima, where there is a hospital. At the end of last year, emergency evacuations in part of the Yanomami area were suspended for ten days when the helicopter, the only means of reaching certain areas, broke down. Leaders report at least eight deaths in this ten-day period, demonstrating how dependency on emergency transfers has grown in the region, due to the instability of healthcare structures.

Mining is one of the main factors behind the health crisis. Under the government of Bolsonaro – an advocate of illegal activity on indigenous lands – the invasion of criminal gold prospectors increased , triggering an explosion of malaria. The invasion of miners was unhindered by the state and made the work of health teams more difficult. Data published in September by SUMAÚMA showed medical centers that provide care for indigenous people within the territory have closed 13 times since 2021, due to conflicts caused by criminals.

The health center in the Homoxi region was one such facility. Taken over by illegal miners in July 2021, it was turned into a fuel depot, and its health team forced to flee. The center remained in this state for over nine months, with no government attempts to remove the criminals and retake control of the building, which belongs to the Brazilian state. At the beginning of last year, an operation to prevent illegal mining was carried out, but soon after government agents left, the criminals returned and burnt down the facility. The reason no child from the health center is listed as malnourished in government data for 2022 is because none were being monitored by health professionals. Before the miners invaded, 41 of the 47 infants in the community were monitored, and 82.9% were malnourished. The health center remains closed, eighteen months after being taken over by criminals.

There are other regions where mining has caused a health tragedy. In Paapiu, one of the areas most affected by criminal activity, 82.6% of children aged five or under who are monitored are malnourished, but only 23 of the 45 children in the area were being observed in 2022. In Aratha-U, another invaded area, 77.9% of children in the same age group are underweight, but 43 are not included in the statistics. In Surucucu, 68.8% of children are malnourished, but 239 of 566 were not monitored in 2022.

It was in Surucucu that, at the beginning of last week, the Brazilian government installed a task force to provide urgent care in a situation of sanitary collapse, following a plea for help from the president of the District Council for Yanomami Indigenous Health, Júnior Hekurari Yanomami. He said he officially requested help from the Bolsonaro Government on several occasions, but never received a reply. Another source who worked at the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples, or Funai, during the Bolsonaro administration, who asked not to be identified for security reasons, said the agency made several requests for help for the Yanomami, all of which were denied. An August 2022 report by The Intercept also revealed that Hutukara, the main Yanomami association, sent 21 letters to public bodies over two years, asking for help because of the violence caused by illegal miners in their territory. These were ignored.

Last Friday, SUMAÚMA revealed that in the four years of Bolsonaro’s presidency, 570 children under the age of five died from so-called “preventable causes”. Some died from malnutrition itself, others from diseases aggravated by being underweight, such as pneumonia, malaria and diarrhea. The data and photos from the report, with children and old people merely skin and bones, shocked the world. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva traveled to Roraima, where part of the Yanomami territory is located, the next day. The government announced a series of urgent care measures for the population, including a situation room, a field hospital and the declaration of a public health emergency. These are measures adopted in epidemics.

Health professionals and Yanomami leaders say it is the worst health situation the territory has faced, and the data is underreported. This will also be the conclusion of a report by experts sent to the Yanomami territory last week to assess the situation.

The Bolsonaro administration argued the Covid-19 pandemic made medical care in the area difficult, without considering that, precisely because of the severity of the disease, care should have increased. After the repercussion caused by the images of the severely malnourished Yanomami, and the data on the deaths of children published by SUMAÚMA, Bolsonaro told his followers that the dire conditions of the indigenous people were a “farce of the left”. The data disclosed in the report, however, are public, and were part of the system that Bolsonaro’s own government oversaw at Brazil’s Indigenous Health Special Secretariat. The former president and his followers chose to ignore the figures with deadly consequences.

Infographic: Rodolfo Almeida/Sumaúma

Recovery difficult

A large number of children in the Yanomami territory suffer chronic malnutrition, which means they have been deprived of necessary calories and nutrients for years. This impacts their development for life. A child may look healthy, but have a height equivalent to that of a much younger child, as the absence of nutrients impairs growth. This can occur due to several factors in addition to the lack of an adequate diet, including common illnesses such as malaria and diarrhea.

The Yanomami previously faced a large wave of invasion by miners before their territory was demarcated in 1992. These miners were expelled in the early 1990s, and only began to return in 2014. The number exploded from 2018 onwards and an estimated 20,000 illegal miners are currently in the protected area. Earlier still, part of the Yanomami area had already been violated by the construction of the North Perimeter road, built under the business-military dictatorship that governed Brazil from 1964 to 1985, and by the entry of religious missionaries into the region. All this exposed the Yanomami, a people who had only recently come into contact with the non-indigenous, to unknown viruses and bacteria. Without immunity, part of the population was wiped out.

Mining also undermines the food sovereignty of the indigenous people, as it drives away the animals they hunt, contaminates fish with mercury and, in many communities, is carried out in such close proximity that it destroys fruit and vegetable plantations. Malaria, spread by miners, also weakens the indigenous, preventing them from searching for food. Those in the camps set up by criminal miners in the middle of the forest also throw waste, such as the feces they produce, in the river. This contaminates the water the indigenous peoples drink, and cook and bathe with, which causes frequent episodes of diarrhea and vomiting.

The images published by SUMAÚMA and by Júnior Hekurari Yanomami on social media also reveal the existence of severe malnutrition, showing exposed ribs and bones, covered only by skin. The body no longer has fat and begins to consume its own proteins, as if it were self-cannibalizing. The little energy it can obtain is used to keep the main organs, especially the brain, working. It is so weakened that it spends its time concentrating on surviving, and cannot even be fed normally once food is obtained, due to the risk of becoming completely unbalanced, explains pediatrician-nutritionist Maria Paula de Albuquerque, general manager of Brazil’s Center of Nutritional Recovery.

“Approaching these severely malnourished children is not a trivial matter. The child has to be fed gradually and slowly,” she says. “They have to have a diet they can tolerate. The intestine is not at its best absorption phase, it has a mucosa that can barely absorb nutrients. If you throw a lot of nutrients into that little tummy, the chance of malabsorption syndrome, which is when the belly becomes large and distended and which causes diarrhea, is very high,” explains de Albuquerque. She says severely malnourished children are up to nine times more likely to die from illnesses such as pneumonia and diarrhea than well-nourished children. “Malnutrition increases the risk of death to a highly significant degree,” she says.

The Lula government is preparing to set up referral centers within the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, with nutritionists to assist with the recovery of the most severe cases. More immediately, it has been delivering basic food baskets to the most affected communities, with the help of donations from all over Brazil. The Brazilian army is now providing aircraft to help with food distribution, something it has not always done: in 2022, 6,000 essential food baskets, out of 18,000 released by the Bolsonaro government, were not delivered in the region because there were no further flight hours available in Funai’s contract with a company in the region. The lack of planes, which prevented the food from reaching the hungry Yanomami, was also reported to the government, according to a Funai source interviewed by SUMAÚMA. It became yet another ignored request in the Yanomami genocide.

Translated by James Young