The blackened gray of burned tree trunks fills kilometers of Pantanal landscape. The fire consumed what was left of the acuri palm leaves, turning the macaws’ favorite fruit to charcoal. Ever since early August, when fire spread over half of Perigara Indigenous Territory, in the state of Mato Grosso, four Boe Bororo firefighters have visited the area each day to account for the losses.

The group walks until it reaches a place where no trees are left. Everything was scorched after the fire broke out on August 3, leaving things as if a bomb had hit Pirizal Village, in the municipality of Barão de Melgaço, 200 kilometers from Mato Grosso’s capital.

Volunteer firefighter, Virgilio Kidemugureu, of the Bororo people, shows the marks of destruction, like burned genipapo

A stump of a tree caught the attention of the firefighters, who were talking among themselves in Boe Wadáru, as the Boe Bororo call their native language. “It’s genipapo. We use it to make paint, dye hair black. It is also used to paint our bodies and as a tea to combat illness. But it all burned up. And we don’t have any more juice this year, or for next year,” says Valdeci Poxireuo, one of the village’s volunteer firefighters, who receives no compensation for battling the blazes.

He continues to count the losses. “We use this Acuri straw to make roofs for the houses. The shoots are used to make fans and baskets for carrying fruit, fish and beiju; we also use it to make baskets to carry fish and floor mats. It’s all gone. There’s no way to fix the roofs before the rain comes,” he says.

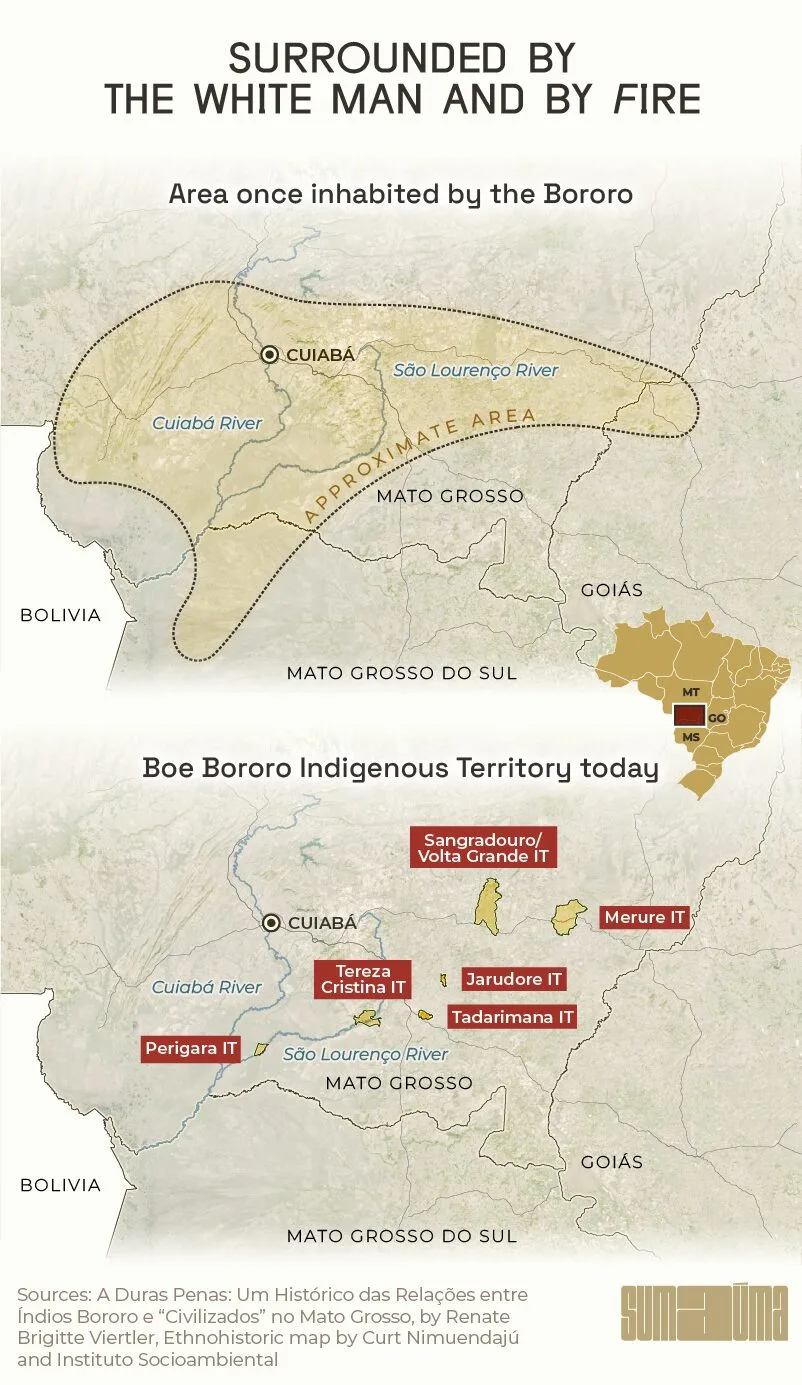

The fires and drought are a new challenge to the existence of the Pantanal’s original inhabitants – the Boe Bororo and the Guató people. Perigara is one tip of what was once the ancestral territory of the Boe, which ran from Bolivia to the Araguaia River, near the state of Goiás, and down the Taquari River, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, according to the Bororo people, an ethnographic map drafted by Curt Nimuendajú, and later studies by anthropologists Claude Lévi-Strauss and Renate Brigitte Viertler.

INFOGRAPHIC: RODOLFO ALMEIDA/SUMAÚMA

Split into groups such as Bororos de Campanha, Cabaçais, Porrudos, Coxiponé or Araripoconé and the Coroados, the Boe people suffered a bloody “pacification” forced by whites starting in 1719, according to Paulo Pitaluga’s critical analysis of the founding of Cuiabá, A Ata de Fundação de Cuiabá, uma Análise Crítica. Explorer Pascoal Moreira Cabral saw gold nuggets on the necks of the Coxiponé Indigenous people (Boe Bororo people) and massacred them, according to anthropologist and Salesian priest Mário Bordigon, a member of the Indigenist Missionary Council and the author of various studies on the Boe.

It was the first end of the world for the Boe.

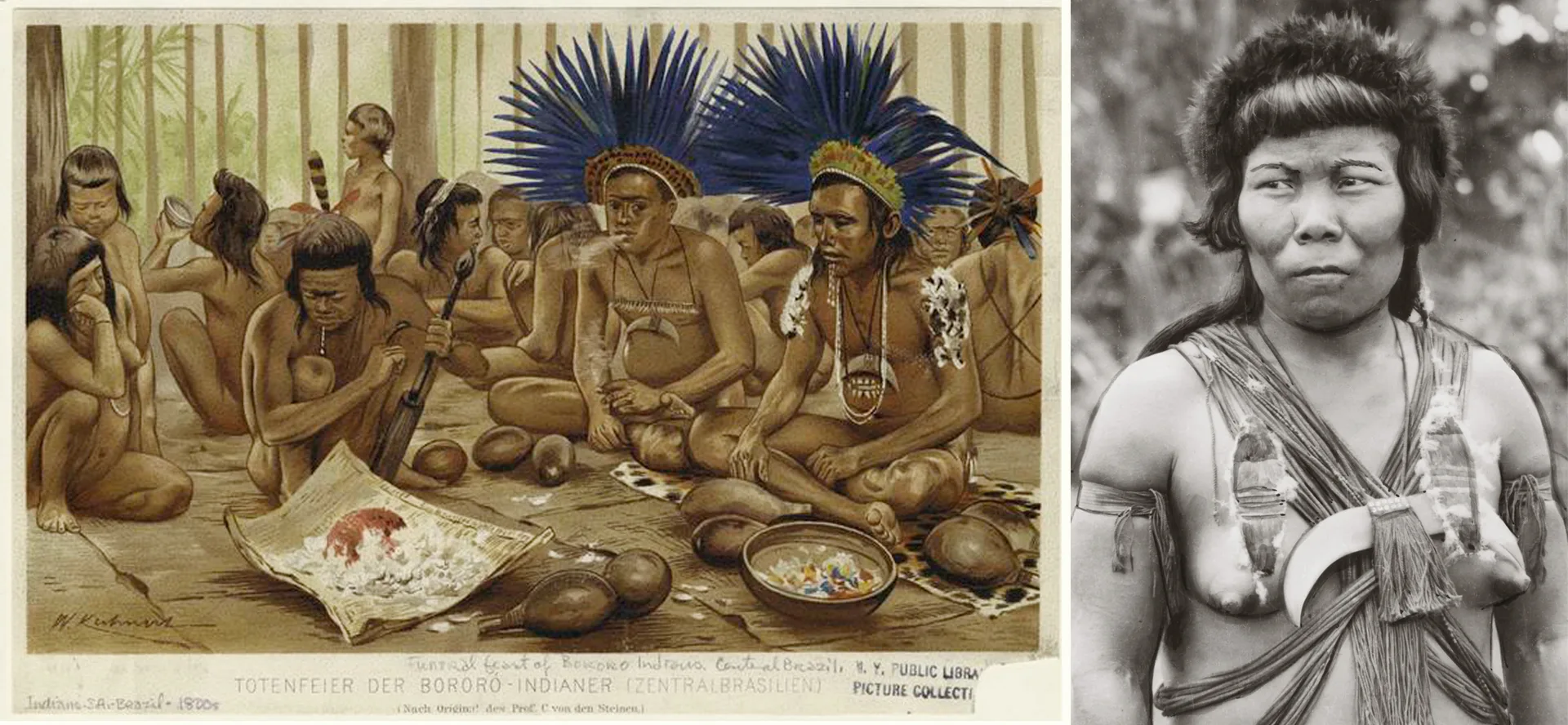

From then to now, countless massacres have piled up in the history of these nearly two-meter-tall warriors who adorned themselves with crowns of macaw feathers, one of ethnology’s most admired feather arts. The last massacre on record was in 1976, says anthropologist Renate Brigitte Viertler, whose book A Duras Penas is a study of the cultural erasure of the Boe.

The last Boe in the Útugo Kúri Dóge (long arrow users) group live in Perigara Indigenous Territory. They migrated there in the first decade of the twentieth century, when the Couto de Magalhães Indigenous Post was built by the Service to Protect Indians and Locate National Workers, the agency that preceded the current Indigenous affairs agency, the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples. It was closed in 1967, following a series of reports of human rights violations. After nearly 100 years as one of the most isolated Indigenous Territories in the Pantanal region, Perigara was splashed across headlines in 2020 when it was hit by a fire that consumed over 30% of the biome. Spread across less than eight small Indigenous Territories, the remaining Boe Bororo and Guató resist in a territory that has yet to recover from the 2020 fires, and now they are facing another wave of fire.

This is the second end of the world for the Boe.

A banquet at a Boe funeral and a Bororo woman: the painting is attributed to Wilhelm Kuhnert (1865-1926) and the portrait, from 1946, is from an unknown author. Photos: public domain/Wikimedia and Brazilian National Archives Collection

“It’s as if it were another contact hit. And the fires always come from private property. There is no record of a fire starting on Indigenous Territory in the Pantanal,” says Jorge Eremites de Oliveira, an archeologist and anthropologist at the Federal University of Pelotas who has spent three decades working with the peoples of the Pantanal.

When a fire invades an Indigenous Territory, in most cases help is slow to arrive or is insufficient. “We asked for help from tractors and to send the plane to dump water, but nobody came. The flames were close to the houses, and only the Indigenous firefighters came to help us. Kids, old people, everyone had to run with cans of water on their heads to save the houses,” says cacique Roberto Maridoprado Bororo, the leader of Pirizal Village.

Life and death, side by side: in Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territory, a local road separates an area spared by the fire from a cemetery of trees

During the rainy season, Perigara is cut off and only accessible by boat, traveling down the São Lourenço River, a tributary in the Paraguay Basin. By land, the trip takes nearly a day from Cuiabá, passing through a maze of sandy roads. With the fires, the path now includes forest and Cerrado areas in flames.

“I went to the river and had a scare. I saw a band of burned coatis floating in the river. I’d never seen so much of this type of death,” says teacher Rosinete Marido, looking to the gray horizon and the blackened trees in Perigara. The children are the teacher’s foremost concern. “This fire made everyone sick, children and old people. To this day the fire hasn’t stopped. The kids don’t want to come to class anymore since the fire started. They stay home, afraid of the fire returning,” Rosinete says.

VIDEO: JULIANA ARINI/SUMAÚMA

A biome surrounded by fire

The fire used to clear land for pasture is the Pantanal’s number one enemy. Nearly 95% of the fires that affected the region in the first semester of 2024 emerged from private properties, according to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research found on the BDQueimadas platform. The Indigenous people say the fire in Perigara came from another protected area, the Sesc Pantanal Ecological Resort Private Natural Heritage Reserve.

According to information provided to the press by the Sesc Pantanal organization, the unit’s administration had been carrying out experimental fire management since June of this year along with the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, as it had already done in years past. It may have been a bad decision. “One theory is that a hotspot had remained, and with a shift in the wind, it could have spread. Their last fire was on approximately July 15 and the fire came back in less than 20 days. But we need to wait for the investigation,” says Carlos Avallone (Social Democratic Party), a member of the state’s lower house of congress and the president of the State Environment Commission. He wonders why the directors at Sesc Pantanal did not comply with State Decree 927, which has barred any use of fire in Mato Grosso since June 17, because of the state of environmental emergency – a period when burns were banned.

According to the press office at the Sesc Pantanal Ecological Resort Private Natural Heritage Reserve, at the time this report was filed, the firefighting team was working to control the fire and no date had been set to release the results of the investigation. The Mato Grosso State Environment Secretary said the Reserve is under federal jurisdiction.

The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation said the burn done at the Perigara Indigenous Territory in July of this year was authorized by Directive 1150, issued on December 6, 2022. Nevertheless, the agency did not respond regarding the lack of a free, prior and informed consultation of the Boe Bororo and Guató Indigenous peoples, as stipulated by the same directive – because it complies with International Labour Organization Convention 169, to which Brazil is a signatory, and which requires agreement from Indigenous peoples for actions in their territories.

The fires catalyze the historic drought devastating the entire Paraguay River basin. According to Brazil’s National Water and Sanitation Agency, the Pantanal has experienced a quantitative shortage of water resources in the Paraguay’s watershed region. The drought produces a destructive process that feeds on itself, as it causes new fires. The lack of swampy areas expose previously submersed plants, like water hyacinths and macrophytes, providing considerably more organic matter for fire.

The Pantanal is Brazil’s smallest biome, covering 150,355 square kilometers. Animals that are extinct or endangered in other territories still survive there, like the jabiru (a stork standing nearly 3 meters high, its wings and neck red) and the jaguar (the only panther in the Americas). The region, recognized by Unesco as a Biosphere Reserve and Human Heritage Site, has been a National Heritage Site in Brazil since the enactment of the 1988 Federal Constitution. It holds around 263 species of fish, 41 amphibians, 113 reptiles, and 1,682 plants, based on data from the Environment and Climate Change Ministry.

Spoonbills flying in Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territory: the Pantanal, Brazil’s smallest biome, is home to at least 463 bird species

While the law sees the Pantanal as a single biome, for science it is a complex of wet landscapes, governed by the pulse of the rivers’ flooding. The plant life switches between Cerrado, forest, floodplain forest, forest islands, babassu stands, and murundu fields, among others.

“It’s a diverse territory, a complex ecosystem of 74 macro-habitats, identified and spread among various soil types, with the influence of flood zones. A unique region that emerged from contact between the Cerrado, Bolivia’s Chaco vegetation, the Amazon, and the Atlantic Forest. Species from these other biomes can be found in its territory. In the Pantanal, everything depends on the amount of water and soil quality,” explains Cátia Nunes da Cunha, a biologist with a PhD in Ecology who is a researcher at Brazil’s National Institute of Science and Technology in Wet Areas.

This complexity means the behavior of fires in the Pantanal is nearly unpredictable. Fire often seems to be under control, but with the large amount of dry aquatic vegetation during a drought, it can spread underground — where the burn continues for a long time, silently, without any flames or much smoke. “At night, it seems the fire is under control, but in the daytime, when the temperature rises again, fires reappear,” explains Carolina Joana da Silva, a biologist and the director of the Biosphere Reserve of the Pantanal.

Fire resilience is also different in the biome. “The Pantanal’s Cerrado region recovers well from fire, but if the fires enter the forests, where the trees are taller and larger, they tend not to survive, because their bark is thinner. These areas, after the 2020 fire, became large voids of biodiversity,” the researcher says. The situation is so serious that on September 4, at a public hearing of the Federal Senate Environment Commission, environment minister Marina Silva warned that the country is at risk of losing the Pantanal.

In Barão de Melgaço a volunteer firefighter battles the blaze advancing over the Indigenous Territory: environment minister Marina Silva warned that the country is at risk of losing the Pantanal

Endangered rituals of life and death

The Boe believe their people share a soul with the animals and that many of them become macaws after dying – that is why eating these animals is forbidden. Aroe, a Boe’s soul, can live in the body of a jaguar, a bat, or a gull. When a Boe dies, the funeral lasts for months, in a ritual involving singing, hunting, and display of the deceased’s bones. Finally, the meal of souls is served. “But we don’t have any more funerals here,” explains Virgílio Kidemugureu, a historian and one of Perigara’s volunteer Indigenous firefighters of the Bororo people. “The old ones left during the Covid pandemic. There is no Bari (shaman) and Aroe Etawarare (funeral master) to sing,” he adds. In Bororo society, death is a time to reaffirm life. The funeral ritual is vengeance against Bope, the spirit who consumes life. The Boe believe that by occupying the body of other animals, they remain alive. By decimating animals like ocelots and birds, the fires in the Pantanal end up destroying this possibility of a connection after earthly life.

There has been an Indigenous presence in the Pantanal for millenia. Peoples like the Boe and Guató have inhabited the Pantanal since before the emergence of Europe’s major cities. These are the Indigenous peoples who built 8,000 fertile landfills and sowed the Pantanal with acuri, tucum, and macaw palms. Using an elaborate technique of layering shells, bone remains, fish tails and mud, they created important refuges for fauna, flora, and men. “The nature in the Pantanal was planted there, just like in the Amazon. The Indigenous peoples were and are the great gardeners there,” explains archeologist Eremites de Oliveira.

With the fire’s advance, the Boe only managed not to lose their entire village because of the help they received from volunteer firefighters from the neighboring Indigenous peoples, including the Bakairi Brigade. Coming from Pakuera Village, in Bakairi Indigenous Territory, in Paranatinga, in Xingu territory, they are regarded as the most experienced at fighting fires in Indigenous areas.

A village in Perigara Territory: studies show Indigenous occupation of the Pantanal that has lasted around 8,000 years

“They were defenseless and hadn’t had any firefighting training. Worse, when we arrived, the fire had jumped the [São Lourenço] river. We crossed to the other side of the river, we fought the fire there and got it under control. We woke up at four in the morning and slept almost midnight,” says Alain Katavga, a Bakairi firefighter, while using a soot-covered yellow uniform to wipe his sweat away.

He has been a Prevfogo firefighter since 2013, a profession without many labor regulations and whose pay hardly exceeds twice the minimum wage in Brazil. It is these agents, along with fire department fighters, who do the most dangerous and exhausting work in the field. “I need to go home, I’m already so tired,” says Alain, barely able to carry his heavy equipment, including a backpack pump weighing over 20 kilos.

‘Argonauts of the Pantanal’

Contrary to his hopes, however, firefighter Alain Katavga cannot go home. After managing to control the fire in Perigara, the five Bakairi firefighters had to head to the Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territory, hit one month later by the same outbreak of fire.

His eyes red and face fatigued, Aldeia Coqueiro had been fighting the Pantanal’s fires in the field for more than 30 days when he met with SUMAÚMA’s team at Coqueiro Village, a Guató community, on August 24. By September 16, the fire had ravaged Guatós Bay, between the Cuiabá and São Lourenço rivers, in a region known for being the home to jaguars. “The jabirus haven’t had a nest for three years. Only this year did I see baby birds, but now, with the fire coming again, they may not hold out,” says Carlos Guató, the cacique of Baía dos Guatós Indigenous Territory, who took us on a boat down the Cuiabá River.

The expedition along the river is a time for the leader to talk more about his people, who have fought against ethnic invisibility since the early twentieth century. Driven from their land and forbidden from speaking their own language and calling themselves Guató, in the 1950s the Brazilian government declared them extinct, and from then to now they have remained almost invisible. Most of what is known as Pantanal culture comes from Guató traditions, like cururu and siriri rhythms, techniques for using arrows to fish, and canoes sculpted from a single tree trunk. In a 1996 book, researcher Jorge Eremites de Oliveira refers to them as the “Argonauts of the Pantanal” because of their centuries-long presence and aquatic civilization.

The fires’ aftermath: Bakairi firefighters in Baía dos Guató Indigenous territory. At right, volunteer Alain Katavga: ‘I need to go home’

According to MapBiomas, the Pantanal was proportionally the biome that burned the most in the country – 59% of its territory was affected by fire at least once between 1985 and 2023. From January to September of this year, nearly 10% of areas have been set ablaze. In proportional terms, that is four times what the Amazon lost in 2007, one of the most intense years for fires, when 3.7% of its territory was ravaged.

The Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Mato Grosso says the fires have by early October already reached nearly half of the 86 Indigenous Territories in Mato Grosso. An emergency campaign was created to help repair the damage. Leaders from the Perigara and Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territories say they will file suits for reparation of damages as soon as the investigation finds the origin of the fires.

At the end of August, Ibama president Rodrigo Antonio de Agostinho told SUMAÚMA that two planes and additional firefighters were sent to fight the fires in the two indigenous lands. SUMAÚMA reached out to the Indigenous affairs agency, Funai, and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples for comment from September 15 to October 8, by email and WhatsApp. Up to now, neither agency has commented on the fires being fought in Indigenous Territories and on reparations for damages.

In Baía dos Guató Indigenous Territory, life insists: a jabiru nest with a baby bird and bird nests in a tree hit by fire

Navigating through what used to be an immense bay has now become difficult. Large rivers like the São Lourenço and the Canada shrink from a lack of rainwater, becoming narrow. The boat’s engine catches on sandbanks. The cacique points to a piece of floating vegetation made up of water hyacinths and macrophytes. He sighs as he says “it’s been four years with hardly any water. You used to lose sight of the riverbanks.” A group of Anhumas – guardian birds of the Pantanal – warn of our passing.

Thick smoke erases the horizon from the waterline, and the animals protect themselves however they can. Hundreds of caimans, capybaras, and giant river otters nest on the white sand beaches. A school of piranhas nearly jumps into the boat.

Carlos, the Guató cacique, and the Cuiabá River: ‘You used to lose sight of the riverbanks,’ he says. ‘It’s been four years with hardly any water’

Next to the Guató area is Encontro das Águas State Park, where one of the world’s largest jaguar populations live. After a few minutes navigating through Indigenous Territory, four jaguars are spotted on the steep riverbanks. First, an orange female with a white chest appears, jumping between plants while she hunts. Two sleepy young cubs are found walking along the banks of the Cuiabá River.

The last animal is a surprise. A large male swims and dives, before then leaping onto the beach to shake himself dry. Irritation on his face, after failing to capture a caiman, he sits on a fallen fig tree. A tracking collar is on his neck.

“It’s Ousado,” says Carlos Guató, recognizing the male jaguar rescued in the 2020 fire and returned to the wild after months at a feline treatment center in Goiás. Several tourist boats come closer to film the animal living at the border between Indigenous Territory and the State Park.

The Guató are exceptional fishers and hunters. In the past, the only threat to the jaguar were their zagaias. This peculiar three-meter-long spear, with a hooked end, was used in hand-to-hand combat against the jaguar, looking the animal in the eye. Carlos Guató looks at Ousado and vents. “Now it’s us and the jaguars in the same boat, all running from the fire.”

A few kilometers away from Ousado is a new line of fire. A column of white smoke fills the horizon. Just like the largest feline in the Americas, the Guató are a people who resist the many threats to the Pantanal. And they hope to avoid the next end of the world.

Surrounded by fire again: Ousado, the male jaguar rescued from the 2020 fires. In the past, only hunters’ spears were a threat

Report and text: Juliana Arini

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Photos: Rogério Florentino

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum

Hyacinth macaw, a bird the Boe regard as soul siblings: the Indigenous people believe many become macaws after death, which is why eating these birds is forbidden