Reelected governor of Pará in the first round of voting in 2022, with an astonishing showing – 70.41% of valid votes, the highest percentage among Brazil’s gubernatorial candidates – Helder Barbalho (Brazilian Democratic Movement) has found that the Amazon can open doors for him inside and outside of his home state. The Barbalho clan’s youngest member is burnishing his image by defending “sustainability,” the “bioeconomy,” and a “standing forest” – in fact he sees the latter as an “economic asset” to the state. The heir to a political group that has in the past been linked to reports of corruption and land-grabbing (misappropriating public lands), Helder wants to be seen as a “green governor” – an image he can promote through his family’s control of a large part of the print, television, and radio media in Pará.

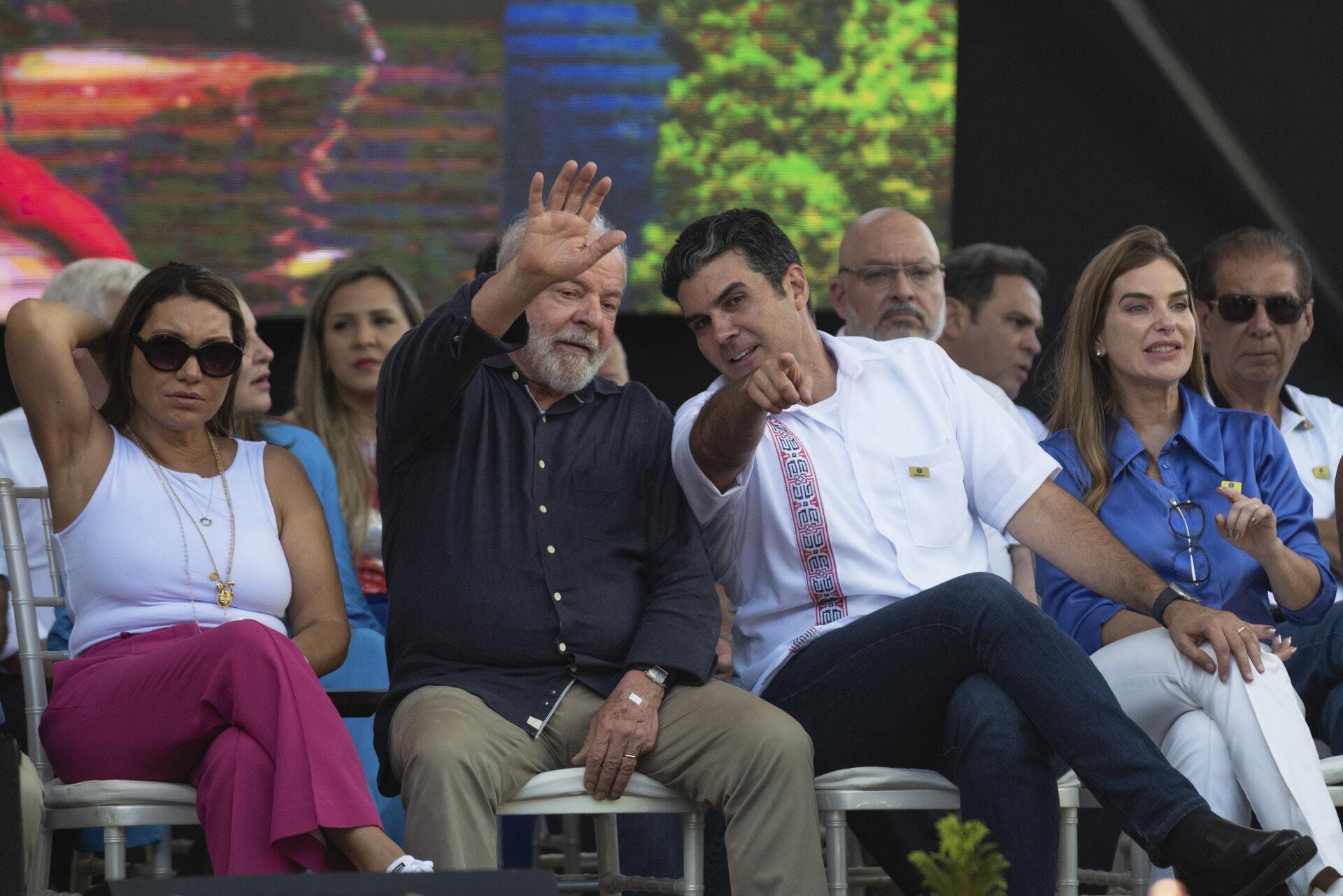

Up to now, Helder has teetered on contradictions: his rhetoric is pro-environment, especially on the international scene, while at the same time the governor supports not only garimpeiros (the miners working in garimpo mining, operations which may be clandestine or legal and that range from small-scale extraction to quasi-industrial mining), having even signed a law in October 2021 to make December 11 Garimpeiro Day, but also transnational mining within Pará. He buffered his political cachet and raised his national profile by aligning with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party) to bring the 30th UN Climate Change Conference (COP-30) to Belém in 2025.

Lula and Helder, together when Belém was announced as the host of the planet’s biggest climate event. The link between them is stronger. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

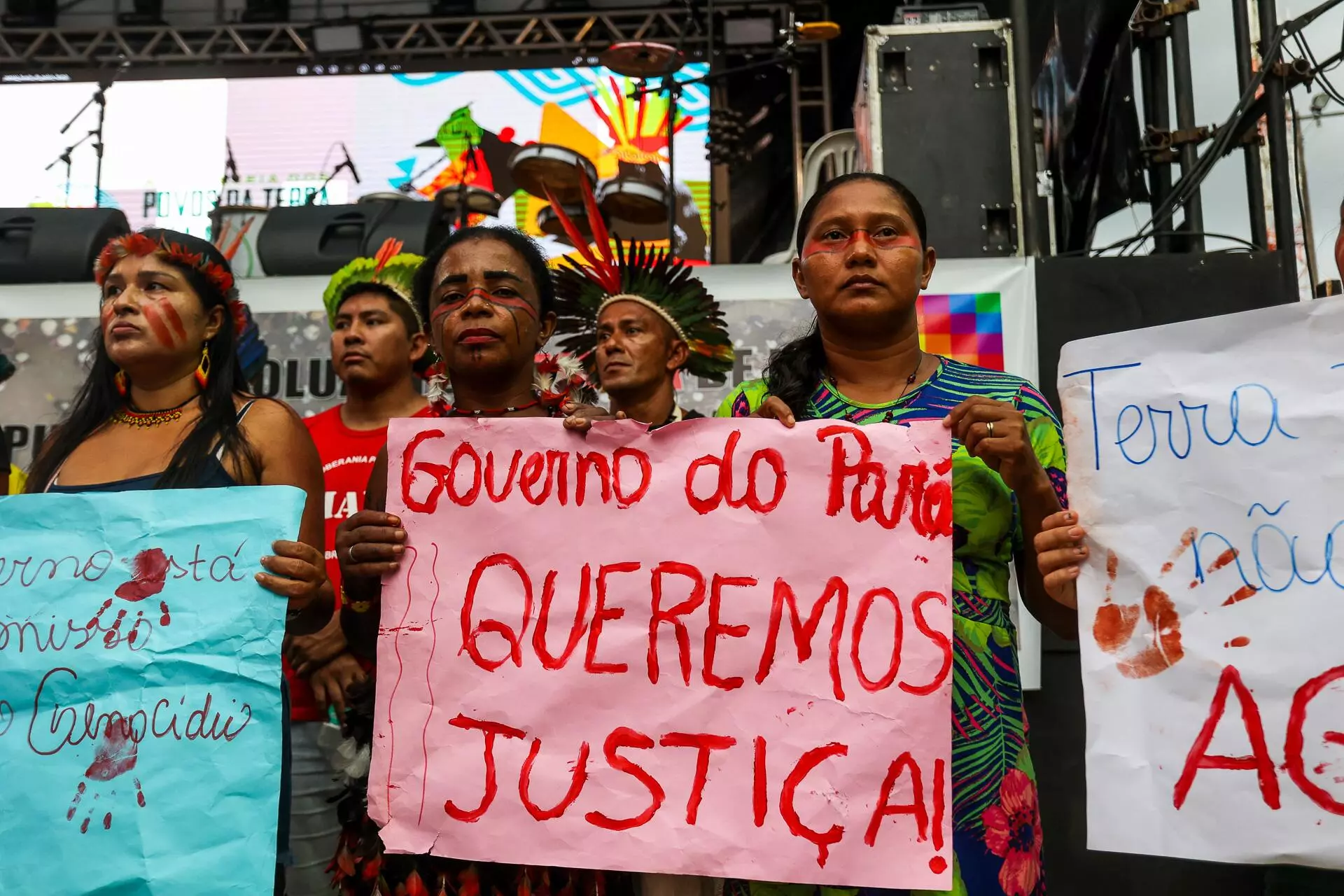

The Amazon Summit, held in Pará’s capital city on August 8 and 9, an event that in practice ended up preparing for the COP, ended without an official commitment from the eight countries with tropical forests to eliminate deforestation and stop the advance of fossil fuel exploration in the Amazon. As the host, Helder Barbalho seized the moment to repeat, in the various interviews he gave to Brazil’s main TV networks, that unless the three sides of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic) were combined, the world will not be able to implement a new model of development. Yet beyond the media flurry, the government was held to account by civil society and the Indigenous movement, for yet another violent attack in the state: three members of the Tembé Indigenous people were shot in the municipality of Tomé-Açu, 200 kilometers (125 miles) from Belém, on the eve of the Summit.

The death of Tembé Indigenous peoples on the eve of the Amazon Summit led to protests against the local government. Photo: Filipe Bispo/Anadolu Agency via AFP

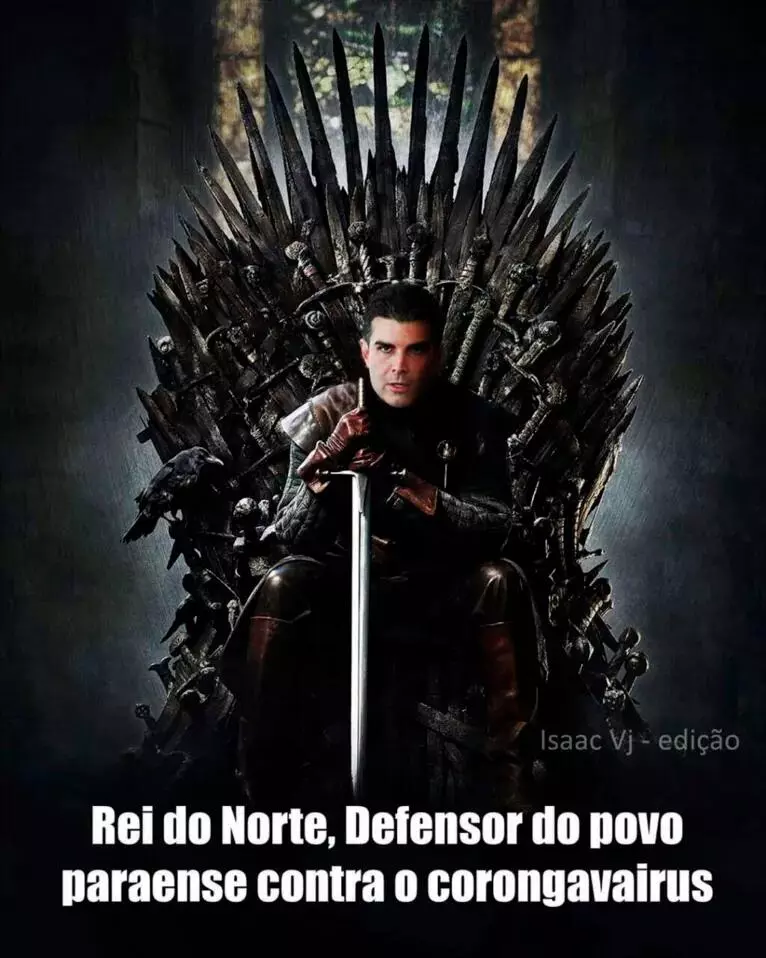

With ambitious plans for his political future, the “King of the North” will have to explain why Pará is a leader in deforestation and continues to be one of the most violent places in the Amazon. The “King of the North” moniker emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic in memes that associated Helder Barbalho with the character of Jon Snow, the King in the North in the Game of Thrones books and TV series. The governor’s responses in a confrontation with then-President Jair Bolsonaro, a denialist of the crisis that killed 700,000 Brazilians, went viral online. With a strong presence online, especially in defense of vaccines, Helder created a communication strategy that rendered him engagement and votes. He currently has nearly 650,000 followers on Instagram alone.

One of the main criticisms environmentalists and climate specialists make of the Pará government’s environmental policies is precisely the fact that there is no commitment to zero deforestation, a goal already undertaken by Lula and one of the topics that dominated debate at the Amazon Summit. “The federal government is responsible for 70% of the state’s areas and without strong cooperation we will not be able to reach this goal,” the governor argued to SUMAÚMA by e-mail. While Helder alleges that the state is unable to carry out oversight of Indigenous territories or federal conservation units, a technical note from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam), warned that “although a considerable portion of deforestation is located on public lands, particularly federal lands, environmental governance in the Amazon is lacking action at every federative and private level.”

The governor, who presents himself as being connected to the global climate agenda, defends studies to explore oil at the mouth of the Amazon River. To do this, he uses a tactic of saying that advancement on this project is “just research” and doesn’t mean exploration. This is the dominant discourse among the Amazon’s political class. “This is not the time for authorizing exploration, but rather for authorizing exploratory drilling. Clearly this exploration should only occur if environmental studies unequivocally show no damage to local ecosystems,” the governor stated in a written message to our reporters.

A state synonymous with deforestation and violence

For seventeen consecutive years, from 2006 to 2022 – a period that includes Helder’s first term – Pará had the highest rates of deforestation in Brazil, according to the country’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). Across all of INPE’s records on deforestation measurements to date, Pará has robbed the planet of around 167,000 square kilometers (a little under 65,000 square miles) of tree cover. It’s almost like wiping a country the size of Portugal off the map, but doing it twice.

There are other harrowing statistics. The state led Brazil in human rights violations committed between 2019 and 2022, according to the latest report from Justiça Global and Terra de Direitos, two organizations that monitor these attacks, released in June of this year. In the period analyzed, which coincides with Helder’s first term, nineteen human rights defenders where murdered in Pará, with a total of 143 violations – including not only the murders, but also threats, attacks, sexual harassment, criminal activities, and suicide.

Pará is also where there are the second most landing strips and garimpo operations in the Amazon (Mato Grosso holds the top spot), including regular and irregular mines: a total of 883, according to a map released in February of this year by MapBiomas, a collaborative network monitoring land use in Brazil. The four municipalities in Brazil with the most landing strips for garimpo mining purposes are located in Pará: Itaituba (255), São Félix do Xingu (86), Altamira (83), and Jacareacanga (53). Two out of the country’s five Indigenous territories with the most landing strips and mined areas are in Pará: Kayapó and Munduruku. Under Brazilian law, garimpo mining is considered illegal when it is practiced on Indigenous lands, in conservation areas, and in public areas whose use is incompatible with mining.

According to national data released last year from the Pastoral Land Commission, in the North region, Pará had the highest number of land conflicts mapped, of violent disputes for land. In 2019, when a premeditated “Burn Day” was scheduled for August 10 to destroy the forests, INPE records showed that on August 10 and 11 alone there were 1,457 hotspots and growth of 1.923% in the number of burns – as compared to the same two days in 2018. Considering the entire year, things grew worse the following years. Except for 2021 (22,876 hotspots), every other year saw more hotspots than in 2019 (30,165). There were 38,603 in 2020, while in 2022 there were 41,421.

Fires in the Amazon in August 2020: under Bolsonaro the forest saw record destruction. Photo: Christian Braga/Greenpeace

Shielded by the family’s media empire

Over one month, SUMAÚMA bore witness to how the media and politicians formed a shield to prevent blows to the image that Helder wants – and has managed – to build. Our reporters asked to interview the governor, department heads, politicians and allies, as well as workers at public agencies that deal with the environmental agenda. These requests went unanswered. On July 21 we received confirmation that the governor would speak with SUMAÚMA in writing. All of the quotes from Helder Barbalho in this report are therefore written responses – they were not spoken during an interview where he could be directly confronted.

Helder Barbalho became governor in January 2019, at just 39 years old. Despite the contradictions swirling around his administration, his reputation as the “King of the North” has gone largely unscathed thanks to powerful political and economic alliances. For his supporters the nickname is praise for his performance and strong personality. For his critics, it is used facetiously and reflects the imperial powers of his administration and his family, as well as Barbalho oligarchy’s old way of acting, now dressed up in more modern and progressive clothing.

During his “reign,” Helder has been able to present himself as a defender of Indigenous peoples, traditional populations, and quilombolas (descendents of enslaved rebels), while at the same time unashamedly supporting mining, embracing “legal garimpo operations,” making countless nods toward the agricultural industry – of which he is himself a part – and maintaining a more-than-cordial relationship with large land owners, many of whom hold lands obtained through misappropriation, despite opposition to him from the Bolsonaro wing of agribusiness, known for its predatory urges.

The climate of trepidation is palpable among public servants, communications professionals, and politicians when it comes to the Helder Barbalho administration. Speaking off the record, five journalists from Belém relayed their everyday difficulties with getting information on government actions and the governor’s schedule. Unlike Lula and other leaders, Helder almost never shares where he will be or who he will see. Only a few events are announced on the government’s official website.

One opposition member says that “the governor doesn’t accept criticism, he has a clear design on power and he surrounds his enemies.” A fellow party member dodged an interview, claiming he was exercising “caution.” In the words of one colleague, who also did not want to be identified, Helder demands deliveries, sets deadlines, and establishes goals. “He’s Pará’s best marketing agent,” says another person working in communications who also only agreed to speak anonymously.

“This is the king of the north, you have to respect him,” a motorcycle taxi driver yelled at the Department of Motor Vehicles in Belém, the opening of which Helder Barbalho attended – he arrived nearly two hours late, surrounded by allies and aides. What was to be the delivery of a revitalized and modernized Department of Motor Vehicles building became a political rally: the auditorium swelled with motorcycle taxi drivers, who drive the main mode of transportation for the state’s low-income population. One of them, chosen as the group’s spokesperson, said that he had been promised a new motorcycle in 2022 if he didn’t support the governor’s reelection. “But I’m with Helder,” he shouted. The governor’s press agent knew that SUMAÚMA was covering the event. Helder found a way to bring the environmental agenda around to administrative routine. Upon signing a line of credit for motorcycle taxis, he let them know: “It has to be a motorcycle that emits less carbon gas into the atmosphere. A state that will host the COP-30 can’t finance increased emissions that cause environmental troubles.”

Of the forty-one state deputies in Pará’s Legislative Assembly, only one, a Bolsonaro supporter, says that he is with the “opposition front.” He is Rogério Barra (Liberal Party), a member of the same party as former President Jair Bolsonaro. Barra is the son of pro-Bolsonaro federal deputy Éder Mauro (Liberal Party) and was the head of the Justice Department during the governor’s first term, but later broke with Helder. Deputy Toni Cunha joined the Liberal Party in late May and now also promises to take a critical tone with the governor. This broad base of support makes it easy for him to govern and pass whatever he pleases in an Assembly currently run by Deputy Francisco “Chicão” Melo (Brazilian Democratic Movement). “He [Chicão] is the Barbalhos’ political operative,” one of the state’s old-guard politicians told SUMAÚMA, asking to remain anonymous. The Assembly’s president canceled an interview with our reporters, claiming that he had to represent the governor at an event, and the press office decided not to reschedule it.

There is an umbilical relationship with the Federation of Agriculture and Livestock of Pará, with the institution’s president, Carlos Xavier, freely moving about in the government. One of the federation’s main points of advocacy is defending the rural battalion, created by Helder to “guarantee the right to land, legal security, and peace in the field.” Among assets claimed by Helder in a statement submitted to the Electoral Court in 2022 are 6,176 head of cattle valued at approximately R$ 12.3 million (around US$ 2.5 million). He also listed his share in Agropecuária Rio Branco, an “ownership interest” worth R$ 1.85 million (around US$ 370,000). His total property on record adds up to R$ 18.75 million (close to US$ 3.9 million).

Helder Barbalho at the kick-off of a campaign to vaccinate cattle herds in Pará. Photo: Marcelo Seabra/Agência Pará. At right, an ICMBio inspection carried out in 2023, at the Nascentes da Serra do Cachimbo Biological Reserve, in Pará: 2,354 head of cattle were removed. Photo: Virgílio Ferraz/ICMBio

He also has a more than friendly relationship with the Accounting Court, to which he supported the appointment of his wife, Daniela Barbalho, as a justice. Former federal Deputy Arnaldo Jordy (Citizenship) filed a citizen suit questioning the appointment, for obvious nepotism. It was temporarily held up by a court ruling, but Pará’s Appellate Court paved the way soon after for the governor’s wife to receive a lifetime appointment to the bench. Receiving R$ 35,000 (around US$ 7,200) per month, she will now render rulings on her own husband’s accounts as a justice on the court.

The COP, Lula, and a national project

His defense of an environmental agenda, using sharp rhetoric in his second term, is what has led to discussion of the Helder name in national political circles as one of the choices to run as Lula’s vice president in 2026, should the Workers’ Party member try for reelection and if his second in command, Geraldo Alckmin (Brazilian Socialist Party), decides to run again for governor of São Paulo If this plan fails to bear fruit, Helder is guaranteed a Senate seat. “His plan is really to be the Senate president,” one veteran politician from Pará ventured.

In a written response, Helder said: “Honestly? This is not a topic for now. My concern lies with delivering on all of the promises we made to the people of Pará, and they are not minor [promises], they are ambitious. The fact that we were able to bring the COP30 to Belém is a huge win, but it is also a huge responsibility.”

Helder and the Barbalho oligarchy are increasingly closer to President Lula, even though the governor did not work to elect the Workers’ Party candidate in the first round of voting in 2022, since Simone Tebet was running as the Brazilian Democratic Movement candidate. Helder’s brother, Jader Filho, took over the Ministry of Cities and is spearheading national deliveries of Minha Casa, Minha Vida, a low-income housing program, which has enormous political and electoral potential. Jader Filho is also the Brazilian Democratic Movement party leader in Pará and handles contacts with the state’s mayors. The Brazilian Democratic Movement governs sixty-one (or 42%) of the state’s 144 municipalities. Seen as the political front that supported and reelected him, over a hundred mayors stand alongside the governor. A Jader Filho run for mayor of Belém in 2024 or for Pará’s governorship in 2026 are on the Barbalho clan’s radar when it comes to taking on the region’s strongest pro-Bolsonaro candidates.

His connection to Lula grew stronger in 2022, when Helder worked with the Legal Amazon Consortium to arrange an invitation for the president-elect to join a delegation to the COP-27 meeting in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. At the planet’s biggest climate event, the governors from Brazil’s Legal Amazon states, led by Helder and with the support of Lula, asked the UN to consider Belém as a candidate for COP30. It worked.

The relationship between Belém’s mayor, Edmilson Rodrigues (Socialism and Liberty Party), and the governor is a partnership, especially in terms of the COP30. In the state’s capital city, he is seen as Helder’s shadow, which displeases his leftist voters. On social media, people joke around with Helder, saying that he is actually the mayor. The main motivation behind City Hall’s orbit around the state could boil down to economics. Belém does not collect any of the ICMS tax levied on goods and services from the mining industry, while these tax funds fill Pará’s coffers.

Helder was not directly involved with municipal elections in 2020, but he was strategic to defeating the pro-Bolsonaro candidate, chief of police Everaldo Jorge Martins Eguchi (a Patriot party member at that time, but now a member of the Liberal Party). ““If the mayor had supported Bolsonaro, with Bolsonaro’s presence here in Belém, Zequinha [Marinho, a pro-Bolsonaro senator] would have gone through to the second round of voting [in the state gubernatorial election, in 2022],” Edmilson Rodrigues told SUMAÚMA during an interview at his office in the Nazaré neighborhood, in the city center. “Likewise, if the governor were hostile to me and I turned into a bucking bronco, even though the Belém municipal government is poor, my difficulties would be substantial, but so would the capacity to ruin the state’s image.”

According to Edmilson, the governor knows that further deforesting Pará is inadmissible. “Helder has already given up on the radical side of agribusiness. Perhaps this means Helder’s, quote unquote, left-ification is positive.” The “left-ification” the mayor is referring to is Helder’s closer relationship with Lula and parties like the Workers’ Party, the Socialism and Liberty Party, and the Sustainability Network party, a strategy for the governor to keep pro-Bolsonaro sentiment from advancing in the state and to allow him to move in an intricate game of political chess.

Helder Barbalho and General Pazuello, a former head of the Health Department: the governor’s countering of the pro-Bolsonaro camp’s denialism has paid off in political dividends. Photo: Alessandro Falco/SUMAÚMA

Since Lula was elected, Zequinha Marinho has been holding meetings in Pará at hubs for illegal land-grabs and deforestation, such as the city of Altamira, aimed at keeping the extreme right active and visible until the next presidential election. Aldo Rebelo (Democratic Labor Party), formerly a Workers’ Party government minister, is part of an “agromilitary” crusade in every state in the Amazon, where he is defending garimpo mining and is articulating with groups of local farmers, as shown in reporting by SUMAÚMA.

Helder has already planned his succession. His deputy governor, Hana Ghassan Tuma (Brazilian Democratic Movement), a career government official lacking in political charisma, is being prepared to take over. She was also appointed president of the COP organizing committee. If she fails to excite voters, the plan may shift to Jader Filho.

The ‘crown jewel’ in the Barbalho oligarchy’s kingdom

Before leaving his post as Minister of National Integration under the Michel Temer administration in April 2018, Helder asked Ricardo Balestreri, who had served as the national secretary of public safety during Lula’s second term, to come to Brasília. Balestreri, who was previously the president of Amnesty International in Brazil, is now the coordinator of public safety and territories for the Arq.Futuro Cities Lab at Insper, a higher learning institution in São Paulo.

“Helder called me to Brasília and asked me a question: ‘How can I sustainably transform public safety in Pará?’ He said the public safety situation in Pará was tragic, dramatic. And it really was. And he knew he would be elected,” Balestreri told SUMAÚMA, during an afternoon of suffocating Amazonian summer heat in Belém, four months after the governor, without notice, relieved him of his position as the head of the Citizenship Articulation department.

Data released in 2019 show that Pará ranked fourth nationally in violent homicides, according to an annual report from Brazil’s National Forum on Public Safety. From 2014 to 2017, violent homicides grew by 19.3%. Belém was the third most violent major city in Brazil, trailing Rio Branco, in the state of Acre, and Fortaleza, in the state of Ceará. Right on the day he took office, on January 1, 2019, Helder had to deal with a massacre. In less than eighteen minutes, five young men were executed at point-blank range in the Cabanagem neighborhood, on the outskirts of Belém. That same year, the governor had to manage one of the biggest prison system crises, second only to the Carandiru massacre, in São Paulo: an uprising at the Altamira Regional Detention Center that left fifty-eight dead. Sixteen inmates were decapitated in clashes between criminal factions. Four more inmates were murdered the next day while being moved to Marabá for holding.

An uprising in the Altamira Regional Detention Center, in Pará, ended in 62 deaths, in 2019. Photo: Thiago Gomes/Agif/Folhapress

A key explanation to his landslide victory in 2022, in a state where 45.25% of the votes went to Bolsonaro and 54.75% to Lula, was the Territories of Peace (TerPaz) social project and the so-called Peace Plants, a public policy created by Balestreri. Rates of violence and criminality in areas where the TerPaz was implemented saw drastic reductions during his first administration and this was regarded as Helder’s biggest success, even by his opposition. Today, the governor is trying to sell the Peace Plants to the federal government and to state administrations as a “model social policy.”

The problem, however, is Pará’s general statistics. There were fewer violent murders in the North region of Brazil, according to the 2023 Annual Report on Brazilian Public Safety. But that wasn’t the case for the state: 2,964 deaths in 2021 versus 2,997 in 2022. Of the fifty most violent cities in the country, seven are in Pará: Altamira, Itaituba, Marabá, Paragominas, Parauapebas, Castanhal, and Marituba. Pará is still Brazil’s sixth most violent state, according to data from the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety. In other words, the situation demands effective action from the government.

Alongside his father, Jader Barbalho (a federal senator and two-time governor of Pará, serving terms in 1983-1987 and 1991-1994) and his mother, Elcione Barbalho (in her seventh term as a lower house member in Brasília), Helder took office during his first term with an awareness that he would need to create his own brand and distance himself from his family’s past and its associations with corruption. He put his money on public safety and promised “honesty and transparency.”

Following a 2013 conviction, Jader, the Barbalho oligarchy’s patriarch, had to return over R$ 2 million (around US$ 400,000) that had been deviated from the former Office of the Superintendent of Amazonian Development. Criminal cases were brought against him in the Federal Supreme Court for misappropriating funds from Banpará bank and for expropriating land belonging to Incra, Brazil’s agrarian reform agency, during the 1980s. The Banpará case reached the Federal Supreme Court for the first time in 1984. In 2015, the Court shelved three cases against Jader after he ran out the statute of limitations. The statute of limitations also ran out on other cases after the senator turned 70. In short: none of these cases were tried in the higher court. Jader has always denied the accusations, but people in Pará like to say: “Never give a Barbalho the keys to the safe.”

In tandem with promises of honesty, Helder announced during his first term that he would create a Citizenship Department, bringing every government agency to the state’s most violent areas. And this was the project that Balestreri would run. “We first came in with the protective police, coming to stay, and we created the atmosphere to come in later with the entire bloc of government departments.”

Balestreri left the position due to political reasons. Helder put his cousin, Igor Normando, in the position – the same person who the Barbalhos have now chosen to run for mayor of Belém in 2024. The flagrant political use of the program by the new government department is already causing unease among officials and in the project’s technical area. Helder could decide not to run his relative if he feels that his welcome in the social area is wearing thin.

Talking out of one side of his mouth to garimpeiros, and out of the other to Indigenous peoples

When pressed to provide answers on how he handled Belém’s candidacy to host the COP, Helder Barbalho speaks along generic lines: “The world has always discussed the Amazon and its importance to the planet’s balance, but little is actually known about the challenges of living and developing in the Amazon. There is nothing fairer than us trying to bring the planet’s biggest geopolitical event here, so that we might sense how the forest can be an asset in this fight against climate change.” This answer points in at least two directions: a regard of the forest as a good/economic asset and an allusion to the idea that the forest’s protection cannot prevent development. The first point is quite popular among investors in Brazil’s southeast and in other countries; the second is discussed among economic elites working in the Amazon’s extractivism community, who usually use “development” to justify the forest’s predation.

When asked if he believes in a new paradigm, where mining and garimpo operations will no longer play leading roles in Pará, the governor says that his administration has nothing against “garimpo mining done legally, following rules and responsibly,” but that “we will not stand illegal garimpo mining.” According to the state’s Transparency Portal, from January to June of this year, Pará collected R$ 565.2 million (around US$ 115 million) from goods and services taxes levied on the mining industry (nearly 6% of the state’s tax revenue).

Brazil’s environmental agency carries out an operation against illegal garimpo mining in the Kayapó Indigenous Territory. Photo: Ascom/Ibama

The relationship between Pará’s governor and the Vale transnational mining concern, which was responsible for the Mariana and Brumadinho disasters, Brazil’s two largest environmental catastrophes to date, is a whole other chapter. Vale, along with Hydro (a Norwegian aluminum multinational), funded the construction of the Peace Plants, the social project that bolstered Helder’s image. Each unit had an estimated average cost of R$ 35 million (US$ 7.1 million), according to Balestreri. Nine have already been built and are up and running. In May the governor announced the goal of implementing forty more in the state. “The governor is a man with his feet on the ground. He works with the rationale that we’re inside of a capitalist system and the mining sector will take precedence. Pará’s wealth comes mostly from mining,” sums up Balestreri, the creator of the Peace Plants.

With this logic, Helder unabashedly demands that Vale and other companies invest in government projects. “Vale has been in Pará for nearly forty years. Its operations exist and will continue to exist, whether or not the state government is partnering [with it],” he wrote to SUMAÚMA. “It’s only fair that the company take some of its massive profits and apply them to benefits for the people of Pará, returning a bit of the enormous wealth it takes from here.”

Vale not only funds the Peace Plants, but it has already announced that it will spend at least R$ 670 million (US$ 136 million) on works for the COP-30, as shown by SUMAÚMA. To justify accepting the continued predatory exploration of one of the forest’s most notorious destroyers in the state of Pará as a done deal, as long as the company continues to finance government works and projects, Helder Barbalho turns to rhetorical maneuvering: “We’re using the funds from the Vale partnership to lessen economic dependence on a model based on mining and agriculture. A greener economy. None of this means that we’re going to let down our guard in terms of obeying the laws and rules of legal mining.”

Vale has the world’s largest largest open-pit iron ore mine, in Canaã dos Carajás, a small town in Pará, located along the banks of Amazon River in Brazil. Photo: Nelson ALMEIDA/AFP

In May 2021, Pará’s Legislative Assembly established a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission to investigate Vale. The political class seems to be establishing an intimidatory relationship with the transnational company for it to continue sapping the forest and to keep Brazil’s largest mining complex in the state. As a result of the parliamentary inquiry, Vale signed an agreement to pay out approximately R$ 3 billion (around US$ 610 million) to help finance the Pará Railway, a regional hospital, nine Peace Plants, and a metalworking hub in Marabá.

Helder acknowledges that Pará’s economy “is based on two pillars: mining and agriculture. Yet he says that it is necessary to have “sustainable” economic alternatives. According to the governor, “it’s not fair that rich countries tie up carbon market regulations while at the same time they talk about preserving the Amazon.” And he adds: “That is why it is fundamental that they come here, to see the place that they speak so much about. See that over twenty-five million Brazilians live here, who need income and social development. Regulating the low-carbon market once and for all is crucial.” It will be “very frustrating,” he continues, if carbon market regulations are not finalized before the COP-30.

An advocate of mining, Helder Barbalho takes part in an event with the Hydro company, in Barcarena, in 2020, during the pandemic. Photo: Marco Santos/Agência Pará

Regarding this controversial topic, the governor has a strategic ally and spokesperson in Congress: his own father The elder Jader Barbalho has authored a bill to regulate the Brazilian Emissions Reduction Market in Brazil. The topic has generated so much interest in Brasília that several proposals by other congressional members were merged together before moving through the house together, and the final outcome is now being considered by the Senate Environment Commission.

The Barbalho patriarch points to Pará’s Amazon Now Plan as an example of long-term strategic vision to reduce emissions. By 2030, emissions should be 37% lower. The governor has already mentioned the possibility of raising the target to 43% by 2035. SUMAÚMA tried to contact Jader through his press office, but he also did not respond to our request for an interview.

‘Sustainability’ without zero deforestation?

The Amazon Now Plan, instituted in 2020, is based on the State Policy on Climate Change, explains Gabriela Savian, a deputy director of public policy at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), which works in partnership with the government of Pará: “Amazon Now is a revised version of the State Plan on Deforestation Prevention, Control, and Alternatives, created a while back [in 2009], except with another perspective, not just of fighting deforestation, but also of economic development.”

Helder Barbalho launched Amazon Now in Madrid, at an event held in parallel with COP25. It was a counterpoint to Bolsonaro’s anti-environmental agenda. The plan, which was warmly received by international actors, stipulates that Pará will achieve carbon neutrality in 2036. This concept means that a balance must be found between the greenhouse gasses that are emitted and how much CO2 nature’s systems can absorb. The problem is that contained in this neutrality model is the idea that a major emitter of gasses, for example, will not necessarily cut its emissions; rather, this emitter will offset them or will partly, but not radically, reduce them.

Pará would be ahead of the game if it prioritized a program to pay for environmental services, compensating indigenous communities, extractive settlements, and sustainable development communities, which really help to keep the forest standing, says Brenda Brito, an associate researcher with the Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (Imazon) who holds a doctorate in the Science of the Law from Stanford University. Up until 2021, Pará was the Brazilian state with the most deforestation and the most greenhouse gas emissions, Brito recalls. The targets in the Amazon Now State Plan are, she says, insufficient from a scientific standpoint and are underwhelming in light of the federal government’s commitment to reach zero deforestation in 2030. “How are we going to reach zero deforestation if Pará is saying that it alone will deforest 1,500 square kilometers [580 square miles] by 2030?” she asks.

Gabriela Savion says the State Policy on Climate Change stipulates an average reduction of 6% in deforestation from 2019 to 2036. “It’s a gradual reduction until reaching climate neutrality.” She admits that the ideal thing would be to “immediately stop deforestation,” but she says this will only happen once there is a transition that “allows the population to find other types of economies that are not this most devastating type, based on soy or agriculture, or based on the very degradation of the forest.”

“In the last year, we’ve reduced deforestation by 21%, and this year we’re working to also significantly reduce it compared to last year,” Helder promises. The data he cites is from Prodes, a project done by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research to measure deforestation in the country.

The Lands Act of Pará, which shot through the Legislative Assembly and was passed at lightning speed, is another controversial aspect of Helder’s administration which could have negative impacts on deforestation, as environmentalists see it. When it was passed in 2019, around fifty civil society organizations got together to ask the governor to veto the legislation. They feared that the law would give territory to land-grabbers or agents of deforestation, as the checks and social control to prevent this from happening were weak and there were no guarantees that the Constitution would be obeyed. In other words, there was no certainty that hierarchical criteria prioritizing Indigenous, quilombola, and traditional territories would be used in deciding where public and returned land ended up.

One year after the law’s enactment, when Helder’s administration drafted a decree to regulate the Lands Act, it did incorporate a few suggestions from civil society. Nevertheless, there are specialists who still criticize the lack of transparency regarding who is buying public land in the state and why.

In March of this year, Eliane Moreira, a prosecutor with the Pará State Public Prosecutor’s Office, and Ana Carolina Haliuc Bragança, a federal prosecutor in the state of Amazonas, published an article on the JOTA platform where they used technical arguments to show how public policies on land ownership and the environment under Helder Barbalho are favoring the theft of public lands. “We have watched the building of government land policies, engendered by a legislative, administrative, and judicial arsenal that has moved toward a preference to allocate public lands to private concerns and even ratify occupations that are illegal or are not authorized by the government,” they warned.

Through the Access to Information Act, Imazon asked the Lands Institute of Pará (Iterpa) for data on who is being given land deeds as well as for files with maps of these properties. A list of names was provided, but no maps were, making it hard to apply social control and monitoring to land regularization processes. SUMAÚMA requested an interview with the land institute, but also did not receive a response. The same goes for Pará’s Department of Environment and Sustainability.

No peace with Indigenous peoples

Helder Barbalho created the Department of Indigenous Peoples during his second term, following Lula’s creation of the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. “We’ve worked to reforest the state’s minds, institutionally,” said Puyr Tembé, the head of Pará’s Department of Indigenous Peoples, in an audio message sent to SUMAÚMA after asserting that his schedule would make an interview impossible. Puyr’s appointment is far from signaling that peace has been made between the Indigenous peoples and Pará’s government.

Puyr Tembé, the head of Pará’s state department of Indigenous Peoples. Photo: David Alves/Agência Pará

“We see soy fields growing, we see so much wood removed from the forest, we see garimpo mining, which is advancing more and more. And now we see the projects and how all of this will affect all of us,” reported one leader, whose identity is being protected because of attempts already made against their life and who is a constant target of death threats from public land thieves and illegal garimpo mining bosses. “Consultation of Indigenous peoples doesn’t exist. What happens is a conversation with some leaders, in Belém. There is no conversation at the base, with the people suffering from a shortage of water, from invasion by garimpo mining, from water contaminated by garimpo mining, from contamination from agrochemicals, who suffer because there are no public policies in communities.”

The head of the Department of Indigenous Peoples admits there is “a big problem that’s very challenging, which is garimpo mining on Indigenous lands, deforestation, misappropriation of public lands, which shatters peace in the territories, among the Indigenous peoples, and even shatters the peace of those governing.”

Indigenous leaders apprehensively watch the Pará Railway’s advancement, a project seen as a priority by the state’s government, which will connect Marabá with the port of Vila do Conde, in Barcarena, a region already heavily impacted by the mining activities of Norway’s Hydro. In April, the governor signed a memorandum of understanding in Beijing with China’s biggest builder (Communications Construction Company) and with Vale to execute the project. Other fears held by Indigenous people are the result of projects to build forty-four large hydroelectric plants on the Tapajós River and to build the Ferrogrão railway, which would connect Pará to Mato Grosso.

A railway in Canaã dos Carajás, in the state of Pará: Indigenous communities are concerned about large works in the region. Photo: Ricardo Teles/Agência Pará

“There’s this promise of joining development with sustainability. But for us, this doesn’t exist,” says the Indigenous leader who has received death threats. “If the Indigenous peoples, the kids, the leaders, and the women aren’t involved, this doesn’t matter to us.” This leader feels that Helder’s administration is lacking “sensitivity, openness to dialogue, listening, and an understanding of reality.”

The alliance of organized and environmental crime

Among the many contradictions and challenges the Helder Barbalho administration faces in Pará, the most recent and worrisome is the new dynamic of criminality spreading throughout Brazil’s North and Northeast. Regions of the Amazon Rainforest are now “part of surprising criminal phenomena, involving everything from drug factions famous in the southeast to micro-crimes like motorcycle thefts, cell phone robberies, symbolic disputes for territorial control, combined with the presence of firearms and interpersonal violence,” says a 2023 report produced by the Center on Safety and Citizenship Studies. Indigenous villages and traditional populations are the biggest victims of this phenomenon that has hit the Amazon with full force, according to the study. In Pará, the connection between organized crime and environmental crimes is more evident, notes Aiala Colares, a geographer specialized in urban planning and socio-environmental development.

“The establishment of criminal factions did not just occur because of the drug trafficking dynamic, but also because of illegal timber exploration, manganese and cassiterite contraband, theft of public lands, and the advancement of illegal garimpo mining on Indigenous lands in the Tapajós River Valley,” Colares writes in the study. Criminal deforestation and garimpo mining are linked to forced labor, violence against women, sexual exploration, and drug trafficking. Environmental crimes are being incorporated into drug trafficking crimes in the region, she says.

There is no more time to negotiate concrete actions to preserve the rainforests, as the governor himself acknowledges to SUMAÚMA. The scarcity of time to which he refers may be the enemy of his own future political aspirations. To preserve the family’s fiefdom while walking this tightrope, there is already an obvious temptation to repeat backward and antiquated physiological policies that have nothing to do with the progressive image of a “sustainable” politician that he is trying to sell Brazil and the world. Helder Barbalho has still not clearly chosen the forest and the peoples who keep it standing, oftentimes at the cost of their own lives. The oligarchy’s youngest member runs the risk of seeing his reign come to an end: not because of a lack of political skill, but because of nature’s response on a planet undergoing a climactic shift, whose near future depends on conserving the Amazon.

Fact check: Douglas Maia

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photography editing: Lela Beltrão

Page setup: Érica Saboya

Deforestation in the Alto Rio Guamá Indigenous Territory, in Pará, for timber sales, a recurring event in the region. Photo: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace