On the first day of this year, most Brazilians celebrated, with ecstatic joy, the inauguration of a truly democratic government, freeing us from the vile, cruel mob that was deliberately destroying the country. But that festive and long-awaited morning was overshadowed by the death of Joaquim Melo, known as Kim, the owner of the Banca do Largo bookstore, in the historic heart of Manaus, next to the Amazon Theater.

When a person so dear to us departs unexpectedly, everything around us seems empty, and our souls are torn apart by the absence of those no longer with us. Faced with this shock, a verse from [famed Brazilian poet, Miguel] Bandeira came to mind: “life is betrayal”.

Joaquim Melo was a bookseller admired and loved not only by readers, but by everyone who knew him. The Banca do Largo was featured in Brazil’s Piauí magazine and Le Monde; a recent article in the British newspaper The Guardian said “the tiny bookshop contains the world’s largest collection of titles by Amazonian writers”. It isn’t an exaggeration. Kim had a huge collection of books on every region of the Amazon: old and contemporary editions, written by both Brazilian and foreign writers. But Joaquim’s interest and passion for culture was not limited to the acquisition of rare books. He was not a collector, moved by a desire for completeness. To an attentive and expert gaze that sought out books, records, albums and postcards, was added a close connection to local, popular culture. He was almost a cultural institution in the daily life of Manaus, as he disseminated music, cinema, books of literature, journalism, the human sciences and scientific research; and gathered hundreds of people together in São Sebastião square, where he organized book launches, concerts, conversations with writers, journalists, and scientists. In a city as maltreated and long-suffering as Manaus, where public education and culture have never been priorities, Joaquim was a compass. He gathered, united and welcomed people, and in doing so, stood against dispersion, neglect and indifference.

In addition to being an exceptional bookseller and lover of the arts – something that says a lot about the demands of the profession – he was also a researcher, with a master’s degree in Society and Culture in the Amazon. Joaquim’s modesty and introspective air – “a discreet hero of the Amazon”, as the journalist Claudio Leal accurately put it – seemed to mask his intellectual background, which was, however, revealed in conversations with those who passed by the Banca do Largo. Many of these passers-by became friends, magnetized by his kindness. Friendship occupied a central place in Joaquim’s life.

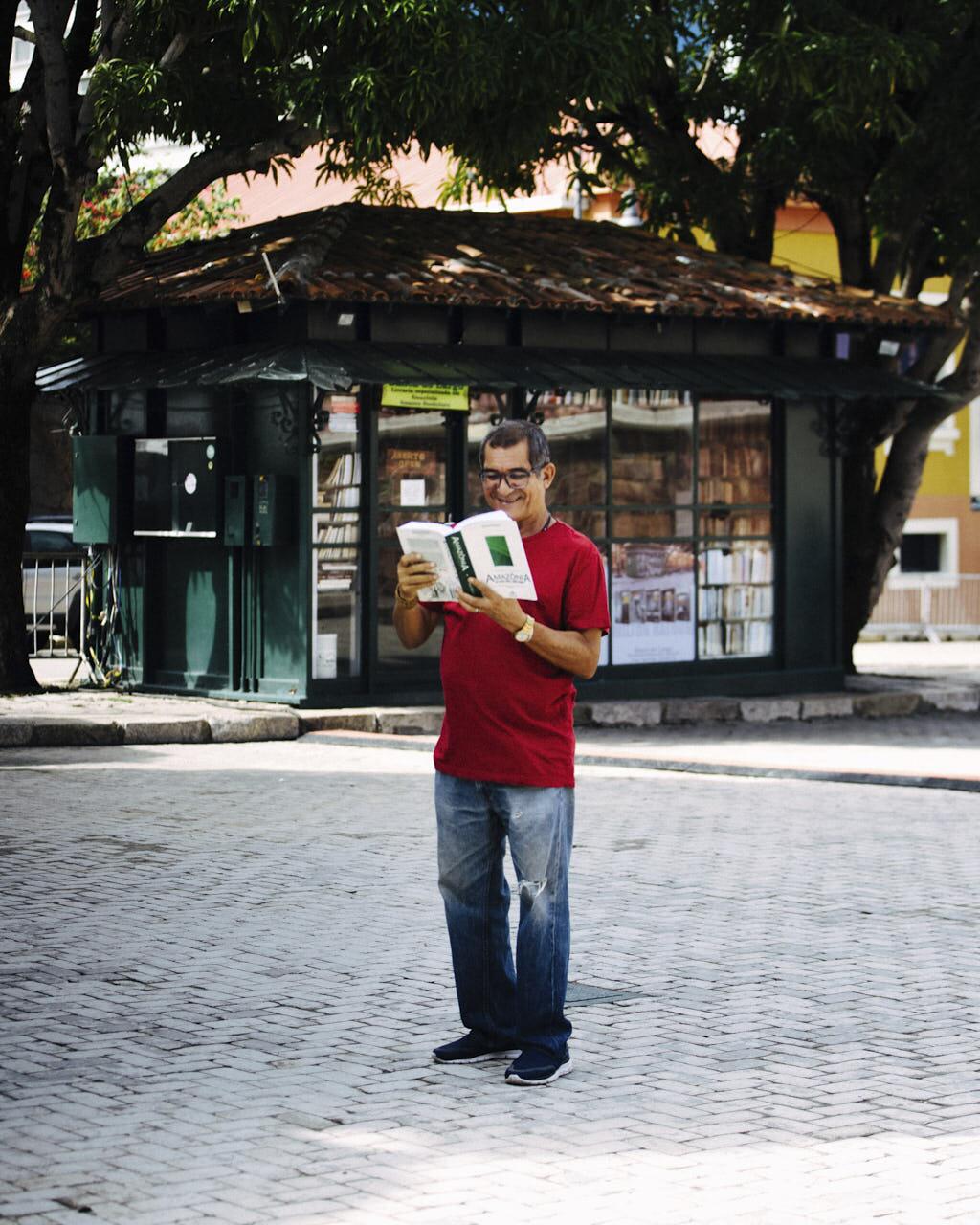

AMAZON-BORN BOOKSELLER JOAQUIM MELO (1958-2023) AT THE BANCA DO LARGO, IN MANAUS. PHOTO: CHRISTIAN BRAGA/SUMAÚMA

Friendship presupposes a pact of equality and reciprocity. This immemorial pact, so rare today, is what we call hospitality: an affectionate welcome, rather than indifference, hostility or simple commerce.

The Banca do Largo, crammed with books, was a small stage of hospitality, a stage that extended to the square, making it a cordial spot to welcome people and exchange ideas. The small space of Banca grew in all directions, and within it inhabited the Amazon, thought about, written and visited by tourists and readers from all latitudes.

Joaquim’s generosity made me reflect on the concepts of gift and alliance, studied by Marcel Mauss and later developed by a number of anthropologists, including Lévi-Strauss.[i]

The gift produces various types of alliance: matrimonial, political, religious, economic, legal and diplomatic.[ii] The last deals with the personal relationships of hospitality, and in it lay a constitutive moral quality of Joaquim Melo, one of the most fascinating traits of his way of being. The donation – material or symbolic – brings the giver closer to the receiver, and makes the two more alike. But Joaquim’s generosity was Cyclopean, Amazonian, to the point of embarrassing me and, undoubtedly, many of his other friends. How to reciprocate? Given that Joaquim wasn’t looking for equivalent generosity, or balances.

In this era of the deliberate destruction of nature, rampant consumerism, unhealthy narcissism and the metaverse (or should it be murder-verse?), Joaquim was committed to forming readers and, while hardly rich, donated books to students and readers from humble backgrounds, something I witnessed on several occasions. He gave all of himself that he could, in a gesture of profound generosity, where affection was paramount.

A few weeks ago, he chose and commented on ten introductory books about the Amazon for “SUMAÚMA – Journalism from the Center of the World”, which, in the same issue, published a beautiful and moving article about Joaquim and the Banca do Largo. He was still full of life, and only the most malign spirits of the forest could have foretold the death of our friend.

It would be difficult to record all of Joaquim Melo’s donations and gifts, and not only for me. But I’ll mention two or three that touched me deeply. I’ve been living in São Paulo for two decades, and when Joaquim knew I really missed the fish, flour and fruits of the Amazon, he sent styrofoam boxes full of tambaqui, jaraqui, packets of farinha d’água and Uarini (types of manioc flour), jars of bacuri fruit jam… It was a festival: a festival of gifts. But how to repay him? I remember saying to Joaquim with bewildered joy: You’re crazy, my friend.

“Not me,” he laughed. “Crazy is putting up with eating tilapia (a commonly eaten fish in Brazil) while dreaming of grilled tambaqui and fried jaraqui.”

But it didn’t stop there. Once, on my birthday, I received a book: a first edition of Vidas Secas (a classic of Brazilian literature, translated into English as Barren Lives) signed by [the author] Graciliano Ramos. When I thanked him, Joaquim recalled how I had published a piece on Vidas Secas and dedicated it to him. Then he uttered these words, like a true anthropologist: “One day you’re a guest, man; the next, you’re the host”.

In 2008, when I launched my novel Orphans of Eldorado at the Banca do Largo, I saw an extremely elderly lady accompanied by Joaquim and another good friend, Professor Renan de Freitas Pinto. I soon realized the elegant lady was the teacher who had taught me how to read and write. Joaquim and Renan (the nephew of Maria Luísa de Freitas Pinto, my old teacher) had arranged the meeting, which was without doubt one of the most emotional of my life.

These and other gifts, when reciprocated, make giver and receiver more alike. But those who received gifts from Joaquim felt indebted. Today I think this feeling – which remained alive, almost like guilt – was, in fact, the continuous exercise of the reciprocal and affectionate gaze of a deep friendship, also marked by distance and the expectation of the next meeting, which phone calls couldn’t make up for. Still on “Kim’s shelf” are the books and records set aside for my March trip to Manaus. Those who maintained a close relationship with Joaquim also gave in to his remarkable generosity.

Joaquim’s interest in and dedication to my work, and his eagerness for my next novel, made me proud, and encouraged me. I remember we had already arranged a launch event for the reissue of Crônica de Duas Cidades: Belém e Manaus (Chronicle of Two Cities: Belém and Manaus, in English), which I wrote in tandem with the sadly also late philosopher, professor and essayist Benedito Nunes. I owe Joaquim for the living presence of my books in my own city, one of the rare metropolises in Brazil with very few bookstores. As we know, gross devastation, greed and ignorance are not limited to the biomes of Brazil, and what is described as “urban modernity” is nothing more than a fallacy.

The loss of Joaquim leaves a legion of orphans. For me and for many others, Manaus will never be the same, and it is as if the heart of our city, already suffering and mistreated, has suffered yet another shock. But Helena Melo and Tereza Rizério, Joaquim’s daughter and wife, respectively, are sure to continue his work. I hope the Legislative Assembly and the Department of Culture of the state of Amazonas make the Banca do Largo a heritage site, in honor of someone who was, for decades, the beacon of Amazonian culture, to which he dedicated himself with enthusiasm.

Joaquim’s river is not the Lethe, the symbol of oblivion. Our friend’s rivers are numerous: that of memory; that of spoken and written words; the Solimões River of his native Tefé; the River Negro, that immense tributary of black waters, home to so many indigenous peoples. In the end, all the regions of the Amazon and their cultures fit into the Banca do Largo, illuminated by Joaquim Melo. Honoring the memory of this great friend is the least we can do for someone who, in life, was a gift to us all.

Translated by James Young

[i] Cf. lanna, Marcos: “Nota sobre Marcel Mauss e o ‘Ensaio sobre a dádiva’” (“Note on Marcel Mauss and ‘The Gift’). Revista de Sociologia e Política (Journal of Sociology and Politics), n. 14, pp. 173-94, jun. 2000.

[ii] Idem.

AMAZON-BORN BOOKSELLER JOAQUIM MELO (1958-2023) IN FRONT OF THE BANCA DO LARGO, IN MANAUS. PHOTO: CHRISTIAN BRAGA/SUMAÚMA