Juarez was born backwards. He came to the world with a future before he even had a past. It was January 30, 1971, and Brazil was also moving backwards. The country was going through the bloodiest period of the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985). The Northeast, his parents’ homeland, was suffering a second year of brutal drought. And the rainfall was atypical in Altamira, Pará, where his family had moved a short time earlier. That morning, under oppressive heat and pouring rain, Maria da Glória Furtado de Araújo gave birth to her eleventh child – the first born in the Amazon.

That recently-arrived baby was also the first, the newspapers of the time celebrated, to be born along the dictatorship’s new promise of progress: the Trans-Amazonian Highway, an 8,000-kilometer-long road planned to rip the forest in half. And because all promises need good propaganda for persuasion, Juarez Furtado de Araújo soon became Juarez Transamazônico, the symbol of the dictatorship’s project to “conquer this gigantic green world,” as was written on the sign at the ceremony to kick off the highway’s construction in Altamira and attended by Dictator-General Emílio Garrastazu Médici.

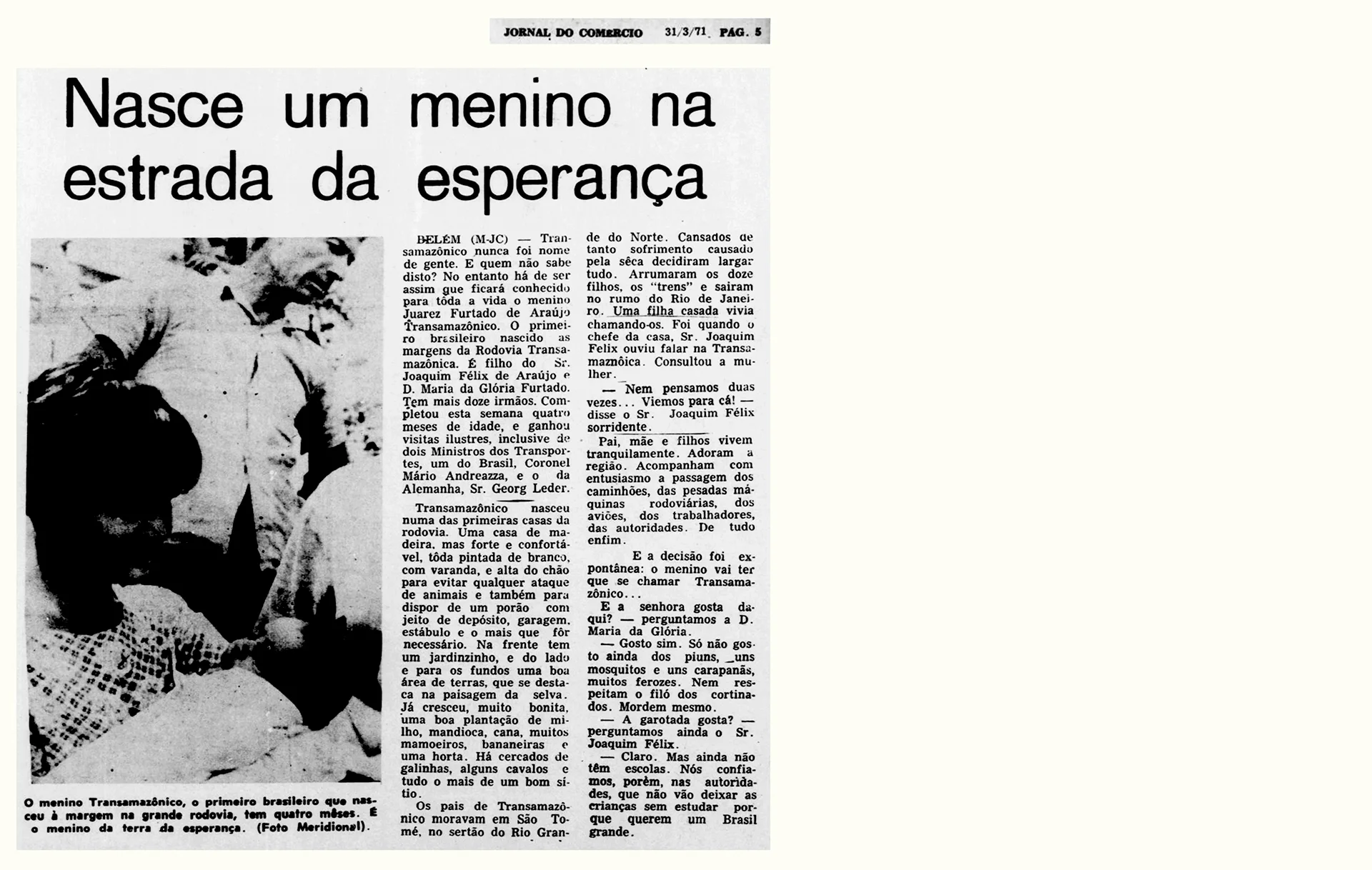

“God bless you, Trans-Amazonian [Highway]!” construction company Queiroz Galvão proclaimed in a half-page ad in Realidade, one of the most popular magazines at the time. Juarez, a naked baby still trying to take his first breaths, was shown from the head down next to the message. In the ad, the company, responsible for the stretch being built near Altamira, made the case for the “first boy to be born in that brave new world,” which it was helping to “raise inside of the world’s largest green area. Where there were only forests. And legends. Fairy tales and fear.” This propaganda-life was also touted by the press. Readers of the March 31 edition of Manaus’s Jornal do Commercio came across his mother, Maria da Glória, cuddling her child, an image evocative of the most famous Maria in the bible. “A boy is born on the road to hope,” the text announced.

Juarez’s birth was used to legitimize the ‘Great Brazil’ ideology. Photos: Reproduced from ‘Realidade’ magazine and from a video in Brazil’s National Archive/YouTube

Just one month before Juarez took the spotlight, Maria da Glória, a farmer from Rio Grande do Norte, had left her drought-stricken lands to embark on a new life with her family in Pará. She was following the promise of Dictator-President Médici (1905-1985), who had launched a program to bring thousands of farmers from the country’s south and northeast to “colonize” the planet’s largest rainforest. They would be given land for planting and support in helping to open what would be the country’s largest highway, connecting Brazil’s north and northeast to Peru and Ecuador.

When Juarez was born, the recently-arrived colonizers were still euphoric about this possibility of a future. This newly-paved ground would set the meeting of two Brazils in concrete: an impoverished Brazil that would remain in the past and a progressive and developed Brazil that was starting to gain life. That was what they believed.

Juarez was given the promise of a future. Yet the boy had no way of knowing this future was impossible. The Trans-Amazonian Highway expressed the military ideology: the forest was a body to be usurped, invaded, explored, and converted into raw materials. Its human communities, like the Indigenous peoples, were not seen as people. Its more-than-humans – other species – were portrayed as savage beasts whose broken bodies were shown in photographs alongside “heroic pioneers.” The world’s largest rainforest, as well as its ancient inhabitants, were things to be subjugated.

Newspapers and magazines from the time exploited Juarez’s image to justify the project to destroy the forest. Photo: Reproduced from the ‘Jornal do Commercio’ newspaper/D.A Press

The colonialist process was violent and decimated many peoples. It is estimated that over 8,000 Indigenous peoples across the Amazon were murdered, some during construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway. Various stretches of the road and its secondary roads could not be paved, making them impassable. Transplanted from their native geographies, without the support promised by the dictatorship, many families just tried repeating what they had done in a radically different climate and region, condemning them to starvation and poverty. Others were contaminated by the official propaganda, amplified by the press, and ventured out to populate the “green desert,” without any promise of official support.

It didn’t take long for the Trans-Amazonian Highway to end up forgotten by the government and the press. And with this, the spotlight on Juarez Transamazônico dimmed and he was no longer news. For decades, researchers, historians, and journalists have tried unsuccessfully to learn his fate.

Until he became a work of fiction.

The legend

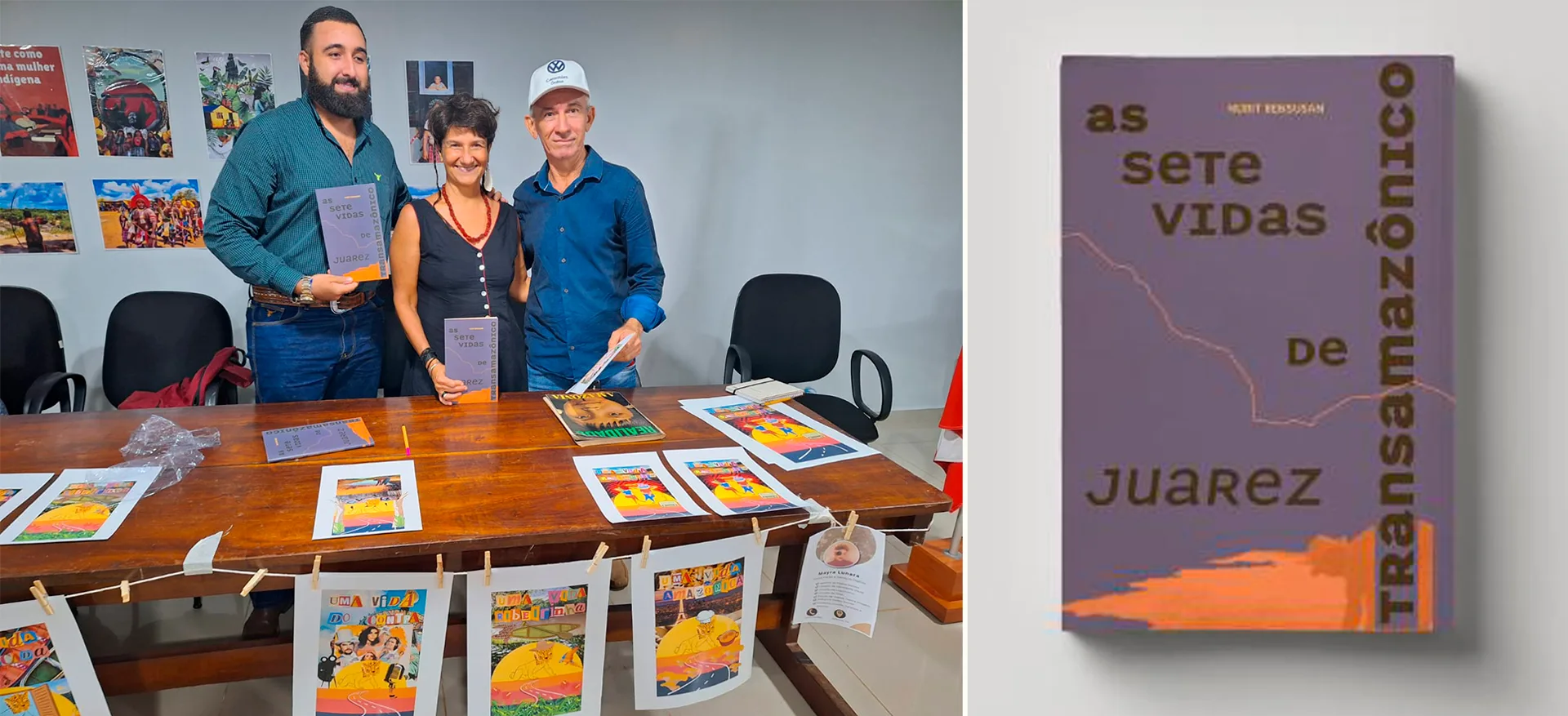

It was early 2024 when biologist and writer Nurit Bensusan decided to release her book “As Sete Vidas de Juarez Transamazônico” (The Seven Lives of Juarez Transamazônico) in Altamira. Interested in the fate of the dictatorship’s posterchild, she imagined how his actual future may have been over 108 pages. In Nurit’s musings, Juarez became a killer, a prospector, and a chef. She could hardly imagine that, on the day she introduced her versions of the story to the world, the real version would also appear.

“Juarez Transamazônico, this living legend! I’m his brother,” announced a voice in the auditorium on the Altamira campus of the Federal University of Pará, where the book launch was being held. It was Mair de Araújo, a 59-year-old farmer. “He and I have a lot of stories to tell!”

Silence settled over the room for a few seconds. No one could hide their bewilderment. Yet shock soon turned to applause. That day, the road and its poster-boy were given a chance, for the first time, to be the protagonists of their own stories. Except that while the concrete lacks the life to reclaim its destiny, Juarez overflows with it.

At the launch event for her book imagining seven destinies for the Trans-Amazonian infant, author Nurit Bensusan (center) saw reality come to life when Mair (right) and Radson, Juarez’s brother and nephew, attended. Photos: Personal archive and IEB Mil Folhas Publishing House

2024: Tieta, Tiazinha, and questions

It is May 27, 2024. Juarez is sitting and waiting in one of the two chairs in his house for Francisco, one of the brothers who often visits him. Sitting at the end of a small street in the city of São Tomé, in the interior of the state of Rio Grande do Norte, the boy of the future’s home is made of cracked cement, bare pipes, walls with no doors, a kitchen with no fridge, and a sink with no countertop. The living room’s emptiness is only interrupted by a busted bedside table. There is nothing set upon it. A bed and a closet share the bedroom, leaving no space to move around. Juarez seems comfortable there, wearing his flip-flops, jean shorts, and a black shirt. He was not born for major highways. His brothers even offer to help him out more, but he likes this space he occupies, alone, in this small rural city of around 10,000 people, the one his parents left in the 1970s with the promise of a future called Transamazônica, returning two years later with another child in their lap and frustration in their hearts.

The boy who grew up in the spotlight now lives alone in the heartland of Rio Grande do Norte. Photo: Brenda Alcântara/SUMAÚMA

Juarez walks every day over the hard ground until he reaches the property owned by his other brother, Juari, where he has some crops. It is around an hour there and another back. He usually spends his afternoons there taking care of his two mares, Tiazinha and Tieta, as well as a small area of the property he was given to plant beans and corn. According to Francisco, this is where his brother calms his mind and feels at ease. “This wealth thing, of wealthy people… I don’t really like it much. What I like is simple people, people like me,” Juarez says.

He was never able to work. He does not know how to read or write and he is partially deaf. He lost his hearing after being improperly treated for measles during his first year of life – a result of exposure to frequent visits from journalists and authorities who came to see the “Trans-Amazonian baby,” his mother believes. His schooling, promised by government ministers and authorities, was never adequately provided. The family was constantly moving to other regions of Brazil, which also did not make it easy for him to have a complete education as a boy.

The peace that Juarez finds each day amidst Nature usually gives way to anxiety at the end of the day, when he returns home and starts looking at his mobile phone, sifting through the past. For decades he has looked for different ways to understand what, after all, his story was. “How did I end up here? For a long time I heard my father say I was an important boy, but after I grew up and wanted to know more, they just told me to ‘forget about it,’ that ‘this is in the past,’” he says. “They also told me the papers at the time announced I’d received an award from the government, that father had been given some property, with all the machinery. Nobody ever saw any of this. That’s why I sit here going crazy: what’s a lie and what’s the truth in my story, in my life?” His voice catches when he starts to remember, but the whites of Juarez’s eyes are naturally red, which makes it hard to know when they are indeed welling up with tears.

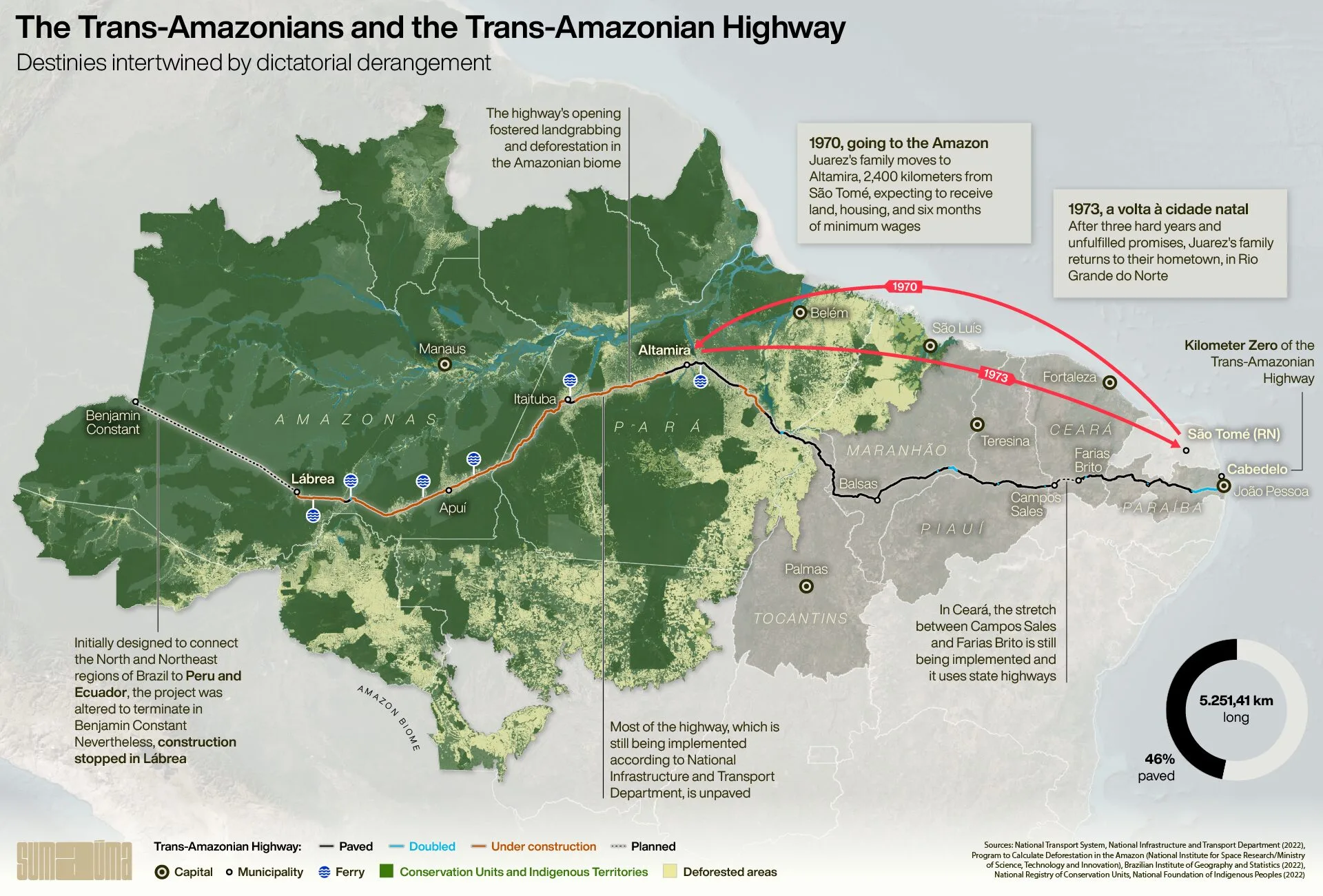

Infographic: Ariel Tonglet

The difficulty in learning about his past also extends to each person’s memories of that time, which are oftentimes jumbled and have been diluted by the passage of time. The family had even kept a box of scraps cut from magazines and newspapers of the day, but it was all lost in one of their many moves back in the 1970s. “Ah, but I remember it was good there, everyone had everything. I just didn’t like the mosquitoes, which they had in droves around there. Médici was a blessing, he was a father to us,” says Juarez’s mother, Maria da Glória, Juarez, now 92.

Her memories are often out of order and imprecise. Some of them are backed up by Maria de Lourdes – or Lourdinha, one of her daughters, who was 18 at the time and who fell in love with the place. Others are corrected by her son Francisco, who was 8 at the time. “The land they gave us wasn’t very good, no. And there was no water. Mother had to ask the neighbors and walk around a kilometer a day to bring us water. I remember she suffered a lot there,” adds Francisco, now 62. “But it was good, you know? That time was really good,” answers Lourdinha, now 72. It was navigating through these stories, which at times built a happy past and at others a memory of suffering, that Juarez tried, for decades, to piece together the puzzle of his childhood. Then came the internet.

A new frontier of discoveries opened up to him around eight years ago, when he started browsing social media and found that he could search for more information about his past online. Because he doesn’t know how to read, he asked for help from one of his daughters – the fruit of a marriage that lasted 14 years. His daughter, who lives in Natal, did a detailed search and started sending her father WhatsApp messages with copies of newspaper pages from that time and other references she found online. The image of Juarez imprinted on the Queiroz Galvão ad, fresh out of his mother’s womb, his umbilical cord still hanging from his body, had never been seen by anyone in the family. Nor do they recall the photo being taken or having authorized any use of likeness – when asked, the construction company had no comment. Much of what came up in this search took the family by surprise, but it confirmed their suspicions: even before he opened his eyes, Juarez had become the poster child of this new Brazil, the country where civilians were kidnapped, tortured, and executed. The country where concrete mattered more than Nature. Where the sound of machines was preferable to that of birds singing. Where the white man’s life was worth more than an Indigenous life – and the pasture more than the forest. Yet they would only find this out later.

“I really wanted to know what actually happened back then, understand why, if they did such a big project and promised so much, they didn’t do anything for my family. Why did they just use me? Did they lie? Was I really an important boy? And after all, can you find out which museum in Rio de Janeiro has my christening gown? I’d really like to go there to see it.”

Juarez’s mother, Maria da Glória, says that dictatory Emílio Garrastazu Médici was his godgather, but he did not attend his christening

1970: The president’s wood

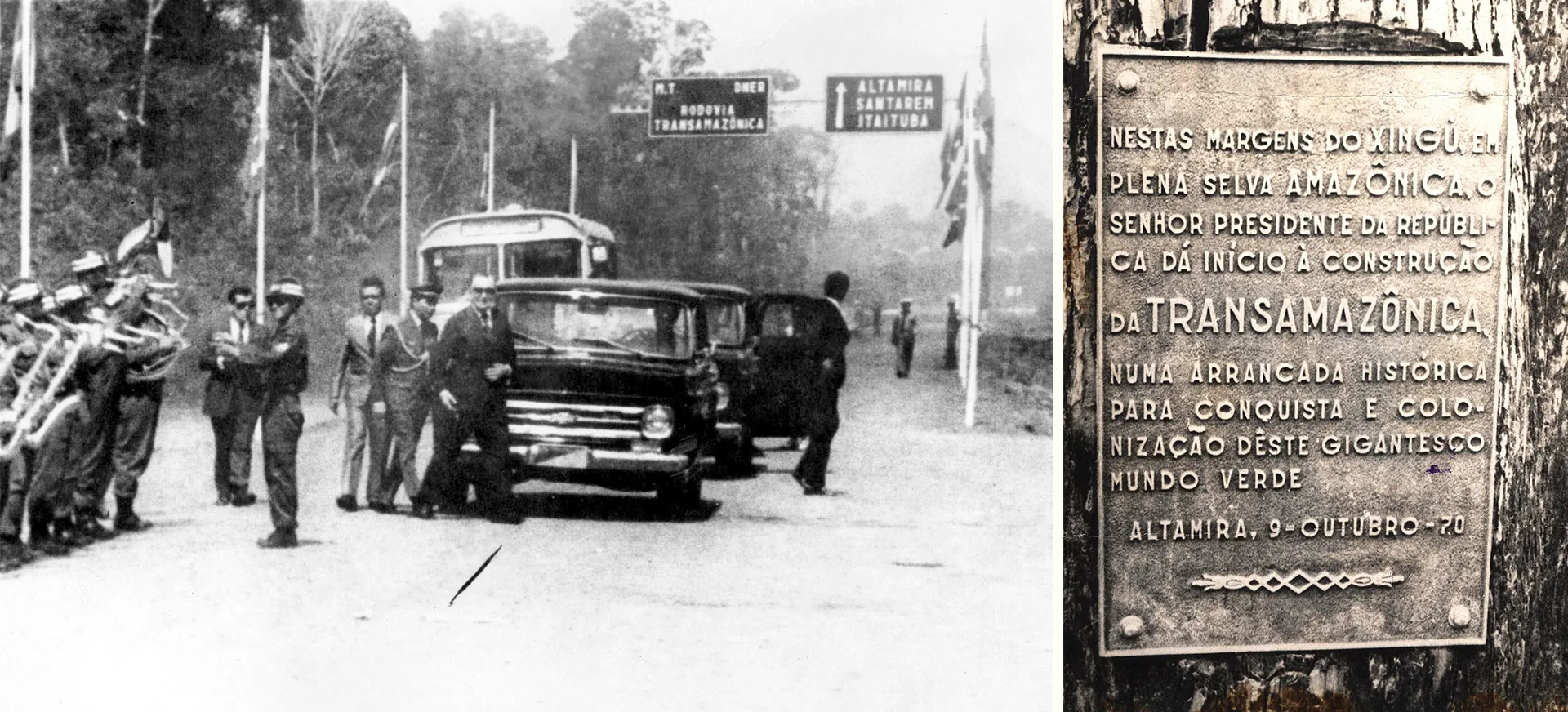

It was during the Médici administration (1969-1974) that the Trans-Amazonian Highway began to rip through the world’s most biodiverse forest. On October 9, 1970, the president was in Altamira, in the heartland of Pará, to officially kick off construction on the highway. Some stretches were already being opened in other regions of the biome, but for a “pharaonic project” like this – as the newspapers of the time described it – the inauguration had to be up to par. That day, the dictator met with a retinue of government ministers and officials along with journalists at a zone seven kilometers away from the city to spearhead the big event of the inauguration: the felling of an over 50-foot tree and the unveiling of a sign, stuck into a Brazil nut tree, that read: “Along these banks of the Xingu, in the middle of the Amazon jungle, the President of the Republic does hereby start the Trans-Amazonian’s construction, in a historic sprint to conquer and colonize this gigantic green world.” The sign’s location became a monument known to this day, with a deliberate double entendre, as the “president’s wood.”

“To the Amazon I bring the government’s confidence and the people’s confidence that the Trans-Amazonian Highway can, after all, be the path to finding its true economic calling and to make it closer and more open to the work of Brazilians from everywhere,” Médici said in his speech.

Dictator Médici, in a block suit and wearing sunglasses, arrives at the place where the first stretch of the Trans-Amazonian Highway was inaugurated, in 1972. At right, a sign commemorating the start of works. Photos: Folhapress

The idea of building the highway had emerged a few months earlier, after the president took a trip to Brazil’s northeast. At the time, the region was suffering from an extreme drought and, according to official records, Médici thought it would be a good idea to move thousands of impoverished farm families from the north and south to “colonize” the Amazon, promoting the region’s agricultural development based on centers built by Brazil’s National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) – what were called agro-villas. “A land with no men for men with no land” was the project’s slogan, referring to territory that had been inhabited for centuries by rubber-tappers, the Quilombola communities of descendents of enslaved rebels, and the traditional Ribeirinho people – as well as by the Indigenous peoples, who had been there for thousands of years. The exhaustively repeated idea that the Amazon was a great demographic desert legitimized the government’s project of arguing that Brazil had to “integrate so as not to surrender” it.

An institutional film from the Office of the President, released by National Public Archives in 1970 shows trees being felled to build the Trans-Amazonian Highway. At the end the narrator says: ‘Roads, occupation, wealth, and integration. The Amazon: a challenge that, together, we’ll overcome.’ Photo: Reproduced from YouTube/Brazil’s National Archives

The dictator’s goal was to resettle 100,000 families, mostly around Altamira, a municipality in Pará that began to be referred to as the “capital of the Trans-Amazonian Highway.” The agrarian reform agency Incra would give each head of household not only moving costs, but also a 100-hectare lot and house, while also paying six months of minimum wages. Under the government’s plans: “75% of the colonizers should be from the northeast and 25% from southern states; […] every five kilometers there shall be secondary roads, cutting across the main road; every 15 kilometers there shall be an agro-villa, with minor services and markets for producers to sell their products; every 50 kilometers, an agropolis, with a medical center and schools […]; and every 100 kilometers, a city with hospitals and more developed urban structures.”

Everything moved very quickly from idea to execution. Days after this trip to the northeast, Decree-Law no. 1106 was enacted, creating the National Integration Program, the main instrument for federal intervention in the Amazon during this time. This official act kicked off the highway intended to connect the entire Amazon – but that soon after was reduced and never finished.

It was more or less in this same period, between August and October of 1970, that family farmer Joaquim Félix de Araújo received an unusual invitation some 2,400 kilometers from Altamira, in downtown São Tomé, Rio Grande do Norte: to be one of the first families from the northeast to colonize the “green hell,” as the military men called the Amazon in propaganda from that time. “Someone from the ANCAR [Northeastern Association of Credit and Rural Assistance] here in Rio Grande do Norte invited father, asked if he would have the courage to go to the Amazon. They clearly explained that he would be given 100 hectares of land, six months of minimum wages, and a bunch of other things,” says Francisco. There was also the promise that the colonizers would receive financing from Banco do Brasil, especially for coffee and cocoa crops, with eight years to pay back their debts.

Joaquim, then 45, was somewhat hesitant, but he signed a document expressing his interest. He owned a small 50-hectare property outside of São Tomé and had suffered from the drought that year and feared for the life of his ten children – his wife, Maria da Glória Furtado de Araújo, was already carrying the eleventh, Juarez. She also was not very sure about the idea of moving and did not want to be far from her aging mother. Yet there was no time to think too much about it.

Juarez visits the home (at left) where he lived with his parents (at right) in São Tomé, Rio Grande do Norte. Photos: Brenda Alcântara/SUMAÚMA and personal archive

The thing is that everything, from promises made to families to destroying the forest to open a path, was done in a rush, without any environmental reports or studies on economic viability. Joaquim and his family were caught by surprise late in the afternoon on December 12, 1970, when a car from the agrarian reform agency pulled up outside of their house to tell them it was time to head to Natal, since the airplane to Pará would leave the next morning. “It was a scramble. We gathered a few clothes and left. Our suitcase was a bag; the padlock, a knot. We and four other families departed for Altamira,” Maria da Glória recalls.

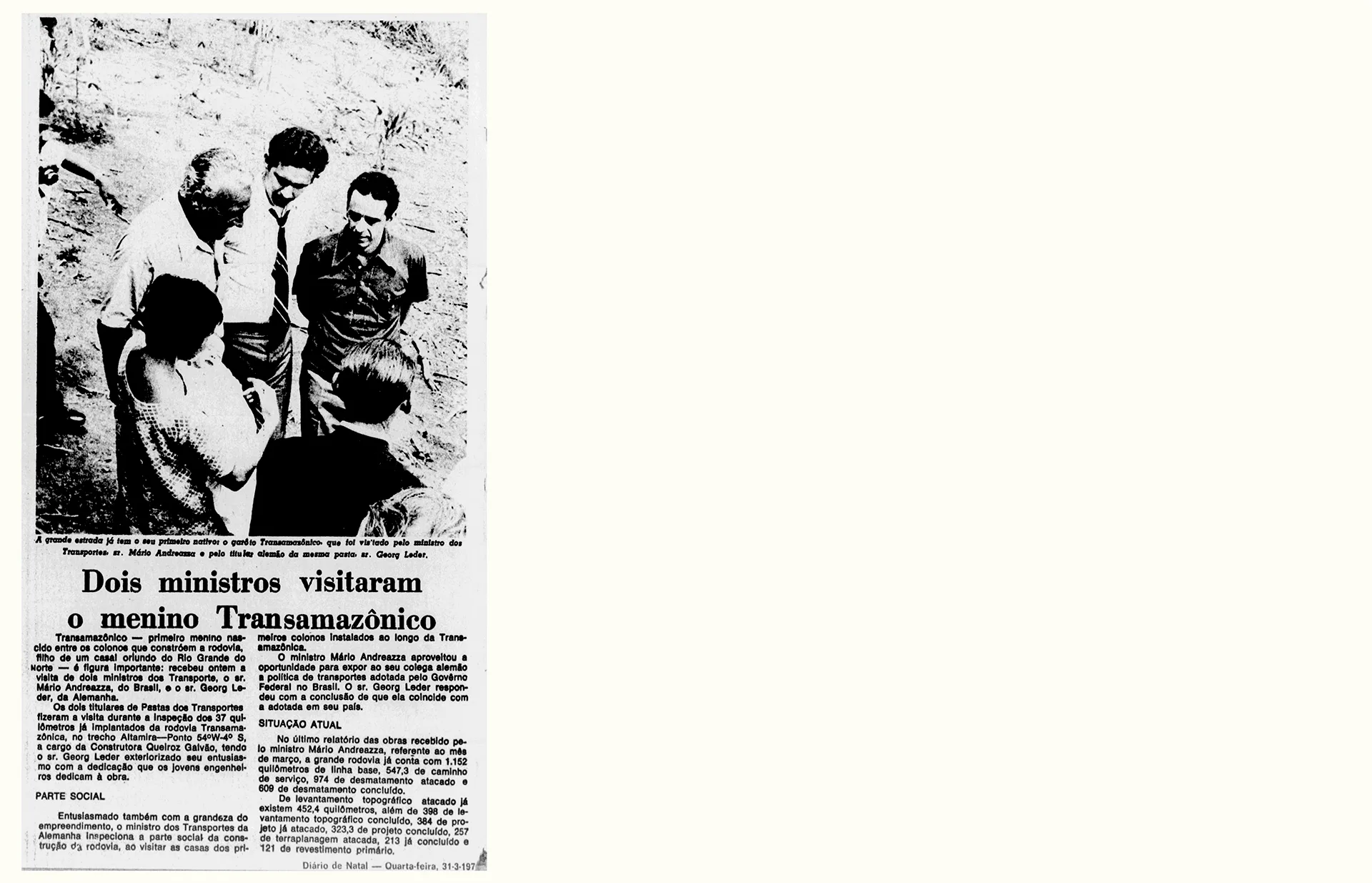

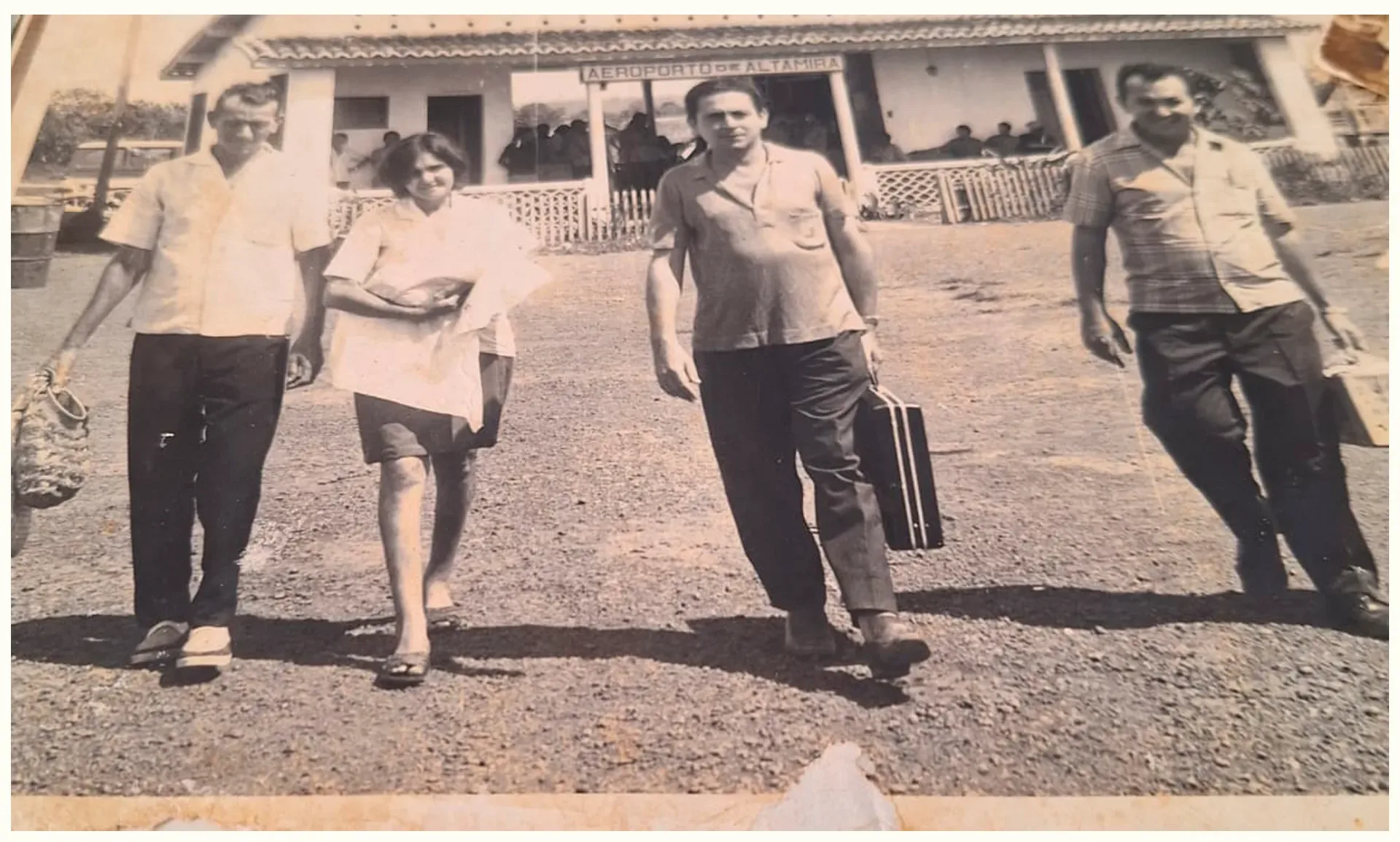

The trip took a few more days: first, they drove to Natal. From there they took a Brazilian Air Force plane to Belém. Upon arriving in Pará’s capital, they took a car to Altamira and then drove along a muddy road to the resettlement area assembled along the margins of the highway’s construction, some 20 kilometers from the city. Once they got there, the houses they had been promised were not ready. They spent a few weeks sharing a tent with other recently-arrived colonizers until they were finally sent to a parcel containing a wooden house painted white and an area that was already deforested and ready for planting. There was not yet any community structure. Schooling, a health post, and recreational areas were kilometers away. It did not matter to the family, because the promises for the future were good. Joaquim was focused on planting 100 hectares of land that promised to be fertile, the children were starting to acclimate to the environment, and Maria da Glória was awaiting the arrival of Juarez, not yet knowing that he would be welcomed with pomp and circumstance by the transport ministers of Brazil, Mário Andreazza, and Germany, Georg Leber, who was visiting the country. Several newspapers reported on the birth at the time and on the countless visits the boy received from authorities in his first months of life. Even before he opened his eyes, Juarez became a symbol of that new-old Brazil.

Enquanto Transamazônico foi útil à ditadura, ministros e outras autoridades fizeram visitas à sua família. Foto: Reprodução do ‘Diário de Natal’/D.A Press

Visitors arrived unannounced. They included members of the agrarian reform agency Incra, authorities arriving in the region to monitor works, journalists, and doctors who needed to make sure the boy was well. “It seems the second baby born there died. So they wanted to maintain my brother as a symbol of that project’s success, use him as a lure for other families to come and colonize,” Francisco says.

Juarez, just a few weeks old, was even invited to take part, along with his parents, in the Flávio Cavalcanti Show, the country’s most popular TV variety show, broadcast Sunday evenings on the TV Tupi network. The family was excited as they traveled to Belém, but there they were told they would have to return. The interview had been canceled and they still do not know why. On April 1, 1971, when he turned two months old, a story in the Diário de Natal newspaper reported that “Father, mother and children lead calm lives. They love the region” and that they “enthusiastically watched as trucks, heavy highway machinery, aircraft, workers, [and] authorities went by.”

Maria da Glória, holding Juarez, and Joaquim (to her right) at the airport on their way to tape a TV show. Photo: Personal archive

That was not exactly the case. The land Joaquim was given sat on rough terrain that was bad for growing the types of crops they were used to tend, access to healthcare was far away and, even with the government fulfilling some of its promises, many colonizers were not satisfied. Recountings by Juarez’s brothers of some of the hardships they experienced at the time match reports collected later by journalists and researchers.

Decades later, another even darker aspect of the Trans-Amazonian Highway was revealed. Volume II of the report issued by Brazil’s National Truth Commission, published in 2014, detailed how the project, which claimed to bring development and integration to the Amazon, actually had devastating consequences for the forest peoples, who suffered violence and deforestation and whose reactions were “harshly repressed by the military and met with extreme violence from henchmen working for the new businessmen and farmers occupying these lands.” The document also shows that, from the time works started, Indigenous women were violated by workers and by employees of the Indigenous affairs agency, and that there was mass mortality among various ethnicities because of the diseases the white man brought to the region.

Perhaps Joaquim began to grow troubled when he noticed some signs of these practices. “One day a caboclo named Zé de Wilson introduced himself to father and explained that some of the land [the government’s agrarian reform agency] Incra had set aside for our family was, actually, the back of his land. Father was very upset about it, so he took some money he had and paid the man. He would never take land from others like that. He didn’t like what had been done,” Francisco recalls. The diseases that struck so many Indigenous people soon came knocking at Joaquim’s door. Nobody knows for sure where the measles came from that nearly killed Juarez when he was eight months old, but his mother attributes both the illness and her son’s deterioration to the constant visits from authorities and journalists. His condition grew so severe that the family decided to rush to baptize Juarez. They did not want their son to die a pagan.

From left to right, the school where Juarez was baptized, in Altamira; his family carrying their baby to his christening; and the certificate of baptism. Photos: Personal archive

1985: promises and absences

“Juarez, listen up, your baptismal godfather died,” Maria da Glória announced to her son on October 9, 1985. She was sitting in the living room of her home in São Tomé when she heard the news on a little battery-operated radio. The radio announcer was reporting the death of dictator Emílio Garrastazu Médici, at 79 years old, from acute renal and respiratory insufficiency due to a stroke. He had died on exactly the same day that, fifteen years earlier, he had felled a Brazil nut tree to celebrate the start of construction on the Trans-Amazonian Highway. Juarez remembers being confused by the news. “I was a little sad. I liked seeing him on television, it made me feel proud. But I also don’t really like how they did things with my family. They went away after they got everything they wanted. And I never met my godfather in person,” Juarez says.

It was not because of a lack of opportunity. On October 6, 1971, while the young boy was burning with fever from the measles, Médici landed in Altamira. He came to visit some of the colonizers, yet he did not go to the home of the boy who was on the brink of death and who served for so many months as the government’s poster-boy. For reasons no one can explain to this day, a decision was made at this time to have Médici be the Trans-Amazonian baby’s baptismal godfather. He did not, however, attend the baptism, which took place one week after his visit. His mother wanted to hurry the baptism because she did not know whether or not he would survive. So it was performed by Father Corrado Falter at the regional school, which had just opened. A church document lists Hudson Costa as his godfather, an engineer who worked in the area and who had served as Médici’s “godfather by proxy.” Maria da Glória recalls that, after the ceremony, the christening gown used by Juarez was taken to be exhibited at a museum in Rio de Janeiro. She does not remember who took it, nor does she have a very clear recollection of where the request came from. At that time, her biggest concern was the survival of her son, who ended up being hospitalized for some time until he recovered.

Médici even returned once more to Altamira. It was in September 1972, when he again arrived with an entourage of authorities and journalists to inaugurate the highway’s first stretch, 1,253 kilometers long and connecting Estreito, Maranhão to Itaituba, Pará. Once more, the president-dictator visited the colonizers and even went to the agro-villa school where Lourdinha was a teacher. There, he greeted some of Juarez’s siblings, but he did not visit his godson.

It did not take long for Joaquim to move his family away. A report in the O Estado de São Paulo newspaper from February 4, 1973, talked a bit about this time. Entitled “An epic that barely left the drawing board,” it reports on the first two years of three colonizer families around Altamira. Joaquim’s was one of them. The excerpt that tells of their saga begins like this: “The Trans-Amazonians have left, say Incra employees.” It goes on to talk about how Juarez’s family was one of the families most afflicted by illness and a lack of credit to buy food, and that before the year ended they had already returned to São Tomé. Perhaps one point in the report provides a good description of the scene: “Going to the Amazon gave the farmers, especially those from the northeast, the chance to trade destitution for poverty.”

Indeed, Joaquim and his family returned to São Tomé when Juarez was almost two years old. Over the next decade, they migrated to various regions of the country until deciding to settle down in their hometown. It was also throughout this period that both the lack of sustainability and lack of competency in the dictatorship’s project for the Amazon became evident. By the end of 1978, fewer than 8,000 families had been resettled when the Colonization Integration Projects were shut down. Most of the colonizers, dissatisfied, had already returned to their hometowns. Only half of the highway’s originally planned length was built, with most of it still unpaved today, making it impassable during rainy periods and giving landgrabbers and the agents of deforestation an easy path into the forest. It was also during the process of colonizing the forest around the Trans-Amazonian Highway that public land thefts consolidated and expanded, which persist to this day and are responsible for making the region one of the world’s most violent for environmental defenders.

The city of São Tomé, Rio Grande do Norte, which the family left to try their luck in the Amazon, and where they returned years later

In rural Rio Grande do Norte, Juarez began to live a more low-key life. Altogether, he had 14 brothers and sisters. Each followed a different destiny. Some, including Mair, who attended the book launch event, still live in Altamira. Others went to live in larger cities. Juarez and another six siblings chose to stay in São Tomé. He was the only one who lived with his parents for nearly his entire life. His family believes that, along with his hearing issues, his mistreated case of measles also left him with psychological side-effects. He has only lived by himself twice. The first time was in 1994; he was 23 and married with three children. Juarez had a routine with his wife, who already had two children from a previous relationship, where she would go to work while he cared for the kids at home. They broke up a few years later and Joaquim moved back in with Joaquim and Maria da Glória for a long time. His ex-wife and kids, whom Juarez has little contact with, have lived in Natal ever since. He only became more independent in 2020, when he started to receive social security payments for the health problems he has accumulated over the years. That was when he bought the house where he lives now, a few blocks from his mom’s house. His father died in 2009.

On that October afternoon in 1985, when Maria da Glória heard about Médici’s death, she looked back on the family’s adventure and felt the whole story had really remained in the past. Not for Juarez.

The walls in Maria da Glória’s house are decorated with pictures of her 14 children; pictured with her are the four who live closest to her

2021: Detours pave a way

In 2021, Juarez and the Trans-Amazonian Highway shared half a century of an interwoven existence. Along the 5,251 kilometers of road that now crosses seven states (Paraíba, Ceará, Piauí, Maranhão, Tocantins, Pará, and Amazonas), deforestation, river pollution, poverty, landgrabbing, organized crime, and widespread violence have become commonplace. Journalists who travel the highway’s passable sections show how the illegal extraction of timber and gold penetrate the forest from the highways and local roads, how the HDI (Human Development Index) in most of the cities built during the dictatorship along the shoulders of the Trans-Amazonian Highway is lower than the national average, and how this project continues to exterminate Indigenous peoples and traditional communities.

At left, the Trans-Amazonian Highway under construction in the 1970s; at right, the highway today, between Itaituba and Jacareacanga. Photos: Folhapress and Michael Dantas/SUMAÚMA

Unaware of the news, Juarez tried to come to terms with his past. It took a while, but in May 2024 he received a surprise audio message from Mair: “Brother, they launched a book here imagining your future. I think now you have a chance to tell your true story.”

A few weeks earlier, Mair was searching YouTube for information on the Trans-Amazonian Highway when he came across an advertisement for Nurit’s book launch. He immediately contacted his niece, an attorney, who sent a message to the book’s author through social media. “I nearly fell over when I read that message and discovered that Juarez was alive,” Nurit says. They had a friendly chat and she invited his family to the book’s launch. She received no confirmation that anyone would attend. As the event was drawing to an end on May 5, she had already lost hope that she would meet the real-life characters behind her work of fiction. That was when Mair raised his hand and asked to speak.

That meeting solved one of the great mysteries of the Trans-Amazonian Highway. To this day, no one had been able to find the boy, because when his mother had registered him with the notary public, she chose to leave off the name of the road. She thought it would be too long and her friends would mock her. The boy of the future was never named Transamazônico. He is, and always has been, Juarez Furtado de Araújo.

It took Juarez over f decades to find out his birth was splashed across an advertisement for construction company Queiroz Galvão

2024: Tieta, Tiazinha, and some answers

It is June 2024 and I’m still trying to stitch together Juarez’s past, weeks after visiting him in São Tomé, when the phone rings. “Hi miss. Did you find out which museum has my christening gown?” Days earlier, the Collection Control and Records Center at the National History Museum had taken inventory and found that there it had not entered (registered in a process) any collection in 1971 or in later years. “Likewise, the clothing collection was searched for all garments related to ‘christening’ and none mention this donation,” reads an e-mail. Museologist and professor Thainá Castro, who was also involved with the search, responded similarly. “Everyone I’ve asked at the museums said they didn’t know the path this object took. There aren’t many other avenues beyond this. The only hypothesis is that it was left somewhere along the way.”

The lost christening gown is a good symbol of the past Juarez has searched for so much. The dictatorship invaded people’s homes and lives, frequently violating them, and out of a few thousand, only fragments are left, some of them still missing, unburied. Yet Juarez’s history sits much less in this brutal past and more in the future he shaped for himself. A future with no inclination for major infrastructure works, but with a vocation for Nature.

It is on his daily walks through the woods, in his thoughtful care of Tieta, Tiazinha, and his bean crops that Juarez weaves his destiny. “This here gives me peace. My mind is at ease,” he says, drawing near the mares. They look happy to see him. They move around in the barn. For a minute Juarez forgets about the christening gown. There, embraced by the woods, he finally feels he is an important boy, just as was claimed in so much past propaganda. But his importance is not because of the dictatorship: it is despite it.

Today Juarez feels at ease when he communes with Nature

Report and text: Jaqueline Sordi

Editing: Talita Bedinelli and Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão e Soll

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Infographics: Ariel Tonglet

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum