From Imperatriz, Maranhão

It was raining heavily in the early morning of February 12, 2005, when Raifran das Neves Sales shot a defenseless 73-year-old woman six times at point blank range. The bleeding body of Sister Dorothy Stang fell to the rain-soaked ground and lay there until late afternoon, when it was transported from the Esperança Sustainable Development Project (a type of Amazon community dedicated to sustainable living and agricultural practice) to the town of Anapu, on the edge of the Trans-Amazonian highway, a journey of 31 miles (50 km) along perilous, poor-quality roads. That same Saturday, with attention focused on Anapu, which lies 430 miles (692 km) from the Pará state capital Belém, Esperança was shaken by another murder – this time of Alberto Xavier Filho, a farmer known as “Cabeludo”, or “Long-hair”, who was killed late at night. While Dorothy Stang’s murder brought journalists from all over the world to Anapu, the death of the little known Cabeludo, a complicated figure who often carried out jobs for the enemies of the Esperança Sustainable Development Project, was ignored, and the links between the two deaths were never connected. But for a man named Geraldo Magela de Almeida Filho, it was the start of a tale of injustice and a 17-year flight which only came to an end in November. It was also the beginning of the life of a traveling salesman named Gaspar.

On the same day that Dorothy Stang was killed, the police falsely accused Magela Filho of being an accomplice in Cabeludo’s murder. For members of the social movements in the Anapu and Altamira region, the motive behind the murder of Dorothy and Magela Filho’s forced exile was the same: the land grabbers wanted to wipe out camponese (small-hold farmer) resistance. “He was a strong leader. The objective was to kill both Geraldo Magela and Dorothy Stang,” says missionary Jane Dwyer, from the Congregation of the Sisters of Notre Dame, a member of the Pastoral Land Commission and Dorothy’s companion in her struggle. “They managed to kill our sister, and send him underground.”

The two murders came at the end of a tense week. Threats against Dorothy Stang’s life had been widely reported to security agencies in Brazil and international organizations. A great deal is known about those who planned, arranged, and carried out her murder, yet Cabeludo’s killing remains unsolved to this day. In 2005, however, the police identified Magela Filho as an accomplice, and the Pará Prosecutor’s Office accused six people of being involved in the crime, identifying a farmer known only as “Claudio” as the killer. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, “after the shooting, the accused Geraldo Magela de Almeida Filho, who had earlier been called by the victim, entered his home and ordered his family not to escape. He then left, along with the other defendants, leaving the victim to die during the night.”

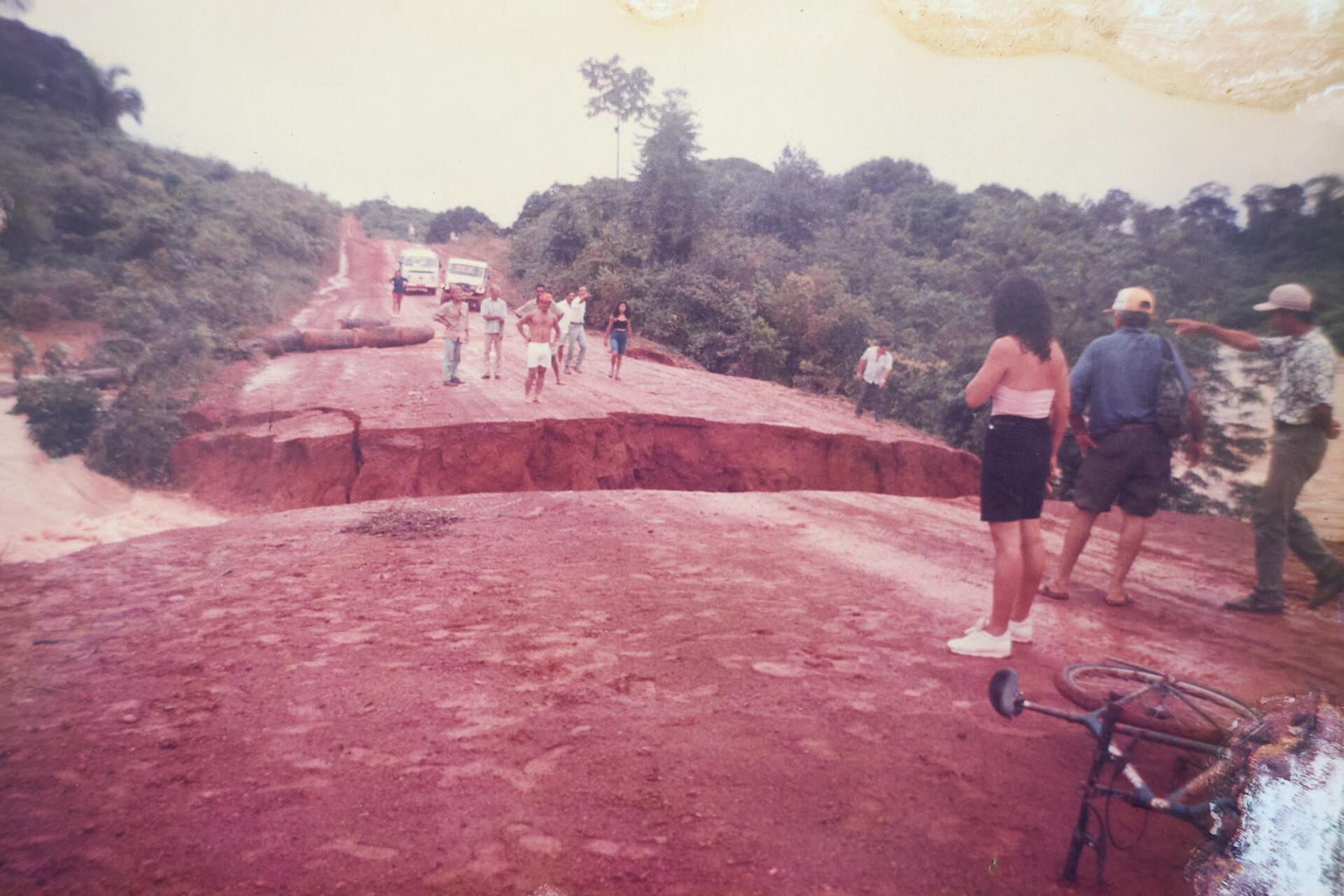

ROAD COLLAPSE ON THE TRANS-AMAZONIAN HIGHWAY NEAR ANAPU, 1990s: during Brazil’s military dictatorship, thousands of poor farmers, like Geraldo Magela’s parents, responded to the call to colonize the area around the highway. Photo: Geraldo Magela Filho personal archive

The charges also cite the statements of Cabeludo’s children, who allegedly witnessed the crime, and that of Lourival Gomes do Nascimento, “who reported having been approached by the group, hours before the crime, when he was threatened by the accused Geraldo Magela, who was carrying a .38 caliber revolver.” As part of the compromised investigation, Magela Filho was arrested. “They [the land grabbers] would then kill him in jail,” says Sister Jane, who still lives in Anapu, today an even more violent place than it was in 2005. Magela Filho then went into hiding for 17 years. He was finally acquitted, by a unanimous decision, by a court in Belém in November.

His attorney, Marco Apolo Santana Leão, says the case of Magela Filho should be seen as part of the persecution and criminalization of social movements. “The leaders are attacked in a number of ways: defamation, threats, physical violence and homicides,” says Santana Leão, who has defended several victims of the destruction of reputation strategy, a form of living death used against defenders of the forest and human rights. In 2018 he represented Father Amaro Lopes, who, after carrying on Dorothy Stang’s work of camponese organization and resistance, was arrested in a police operation more suited to the capture of Al Capone. A series of accusations were made against him, some of them obviously untrue, while a video in which he had consenting homosexual relations with another man was widely circulated in the region. Amaro was released, but the reputation damage had been done. His work on the front lines, defending family farmers against the agribusiness criminals of the Anapu region was ruined.

An agricultural technician and service provider for the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform, Magela Filho played an important role in the pastoral and technical support Dorothy Stang provided for the camponeses settled in the Esperança Sustainable Development Project. He was also a member of the Economic and Ecological Solidarity Association of Amazonian Fruits, deeply engaged in the defense of the forest and the fight against the grabbing of public lands and predatory colonization projects.

Magela had to wait 17 years for justice, but it finally came when, at his trial, his attorney Marco Apolo provided facts, arguments and evidence that led to his unanimous acquittal. Cabeludo’s murder had been carried out at around 11 pm, but on that same night of February 12, 2005, Magela was at the Anapu Police Station filling out the official report of Dorothy Stang’s death. “It was impossible for the accused to be in Esperança and take part in the crime at the same time. Not least because it takes an average of around four hours on poor quality roads and tracks to travel the 31 mile distance between the two locations,” he explained. The lawyer also exposed the illegal procedures used in the investigation, such as the collection of witness statements from Cabeludo’s three children without the presence of an adult, during which the police stated they planned to charge Magela Filho. “The Public Prosecutor’s Office did not even go to Anapu, but simply opened the investigation and charged him,” the lawyer said.

Magela Filho, who was still in hiding, was acquitted without being present at the trial. SUMAÚMA reached him first by telephone, as he traveled the roads of the Amazon. Afterwards, we spent three days with his family and him, so we could tell the tale of a defender of the forest and an activist for agrarian reform, who took almost two decades to save his name, and his freedom.

Magela and his parents, Geraldo and Jovanete. The false accusation against him condemned the family to a painful split. Following his acquittal, they can finally meet in safety. Photo: Adriano Almeida/SUMAÚMA

A story that begins under the dictatorship — Most of the histories of the whites who were installed in the region of the Trans-Amazonian Highway begin with the business-military dictatorship (1964-85), which carried out the greatest forest destruction strategy in the history of Brazil. To follow these human stories is to witness the impact of State violence on the lives of ordinary men and women, such as Magela Filho’s parents, and other migrants.

Born in Varjão dos Crentes, a village of evangelical Christians in the municipal district of Buritirana, in the southwest of the state of Maranhão, Elinete Silva de Almeida had her life transformed when her family decided to try their luck on the highway then being built. She was just two years old, and her family, like those of so many other poor farmers, believed in the dictatorship’s slogan: “The Amazon: a land without men for men without land”. The slogan suggested the many existing residents of the region – indigenous peoples (whose communities had lived in the region for over 10,000 years), quilombolas (descendants of escaped enslaved peoples, who communities had lived there for four centuries) – and ribeirinhos (members of traditional forest communities, whose ancestors had lived in the area for almost 100 years) – were not considered human. The head of the military government General Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1969-1974) inaugurated the highway by cutting down a gigantic chestnut tree in Altamira. His administration then installed colonizing settlements and large-scale agricultural and livestock projects which would benefit from the usurping of public lands.

While Elinete was thrust into this spiral of violence by the hopes of her parents, in Fortaleza, the capital of the state of Ceará, a young Geraldo Magela de Almeida Senior, Magela Filho’s father, now aged 94, watched government propaganda that sought to attract settlers to the Trans-Amazonian region on his black and white television. His wife, Jovanete Nascimento de Almeida, now 74 and a retired teacher, recalls the contrast between the dictatorship’s promises and the reality of occupying a forest that didn’t want them. “It was the most ridiculous thing in the world. In the commercial it said there was a house, school and hospital waiting for us and we only needed to bring our bags. It was just the opposite, and then the suffering began,” she says. She landed in the middle of the Amazon, pregnant with her third child, and later raised six more in the forest. Geraldo Magela de Almeida Filho arrived in the Trans-Amazonian region when he was just two.

Two movements advanced along the Trans-Amazonian highway in the state of Pará: poor farmers who responded to the call to colonize the region, and large-scale landowners, who were allocated 3,000 hectares of land to establish agricultural companies that, for the most part, did not succeed. Among the farmers, on the section of the road that goes from Altamira to Placas, known as the Transa Oeste, or Trans West, there was a predominance of migrants from the south of Brazil, who received more government support; in the other part, from Altamira to Marabá, the Transa Leste, or Trans East, there was a predominance of those from the northeast of the country, who were given little or no support from the State. Those that the generals presented with vast portions of land and funding from the Superintendence for the Development of the Amazon, an organization that would become infamous for corruption, began to furiously usurp public lands in the region, land that even today is riven by bloodshed. Ignoring the condition that they focus on agricultural and livestock businesses, they appropriated the land, and public resources, to devastate the forest and make money through the exploitation of wood.

Magela Filho and Elinete were just children when the Trans-Amazonian highway was built. The road that symbolized “the conquest of the jungle” was just one of many genocidal actions of the dictatorship which, according to an investigation by the Brazilian National Truth Commission, cost the lives of over 8,300 people throughout the region. Over the ruins of the forest, a struggle began between poor farmers, who sought a plot for a subsistence life, and land grabbers.

When Geraldo and Elinete finally met and married in Anapu, their side in this war was clear: they would stand together with the missionary Dorothy Stang and the camponeses, who were fighting for the creation and consolidation of the Sustainable Development Projects, a demand of social movements for a form of territorial occupation in partnership with the forest, which became an official government program in 1999, under the democratic presidency of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. In the 1980s, Geraldo Senior had already been shot in the neck, the bullet exiting through his mouth, while participating in an assembly of settlers that was attacked by a land grabber.

Anapu had become one of the Amazon’s centers of systematic massacres, brought about by the form of occupation and appropriation of land in Brazil and the absence of agrarian reform.

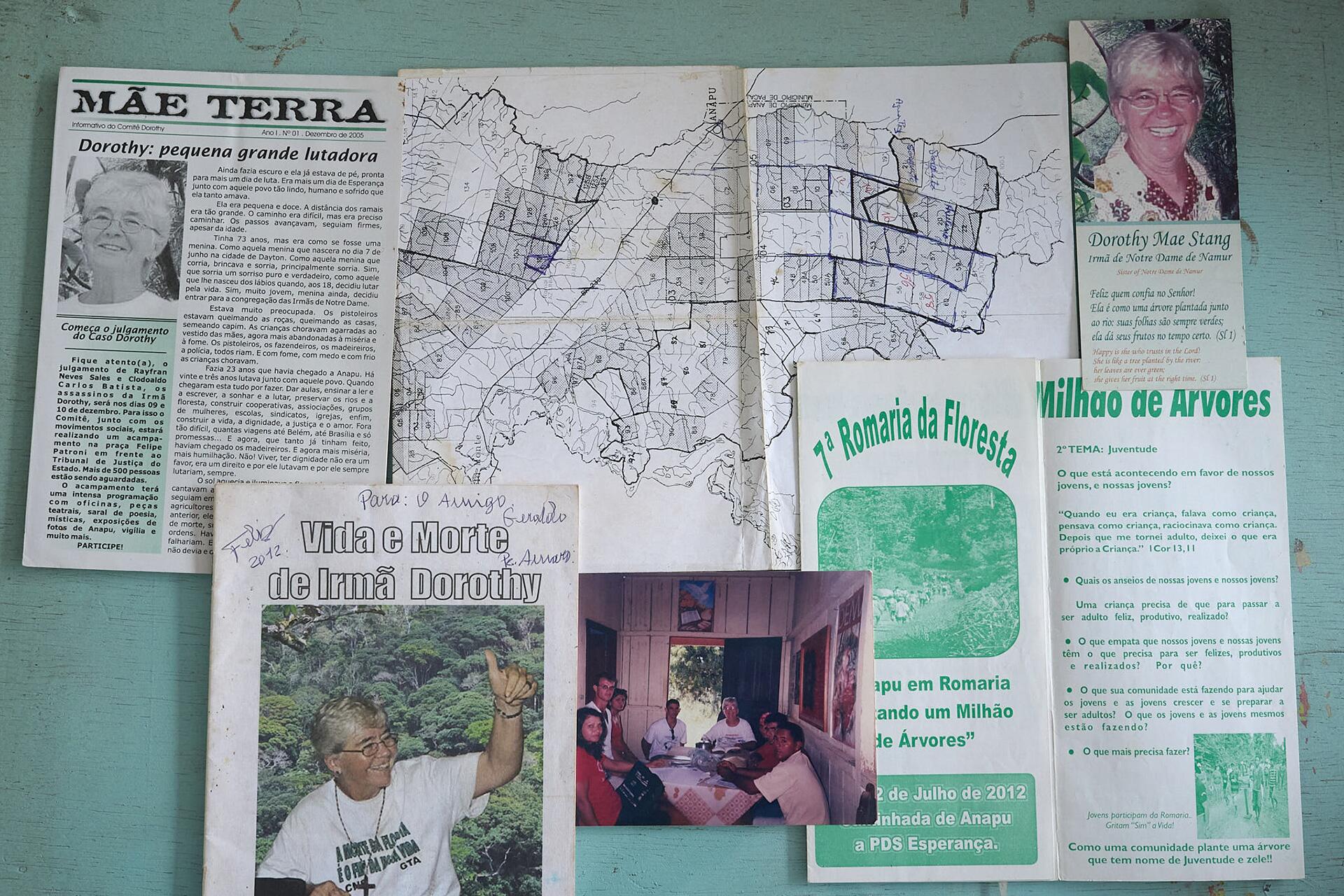

‘When Sister Dorothy Stang arrived, the first task she gave me was to draw a map of the territory,’ recalls Magela, showing the map and other remembrances from that time. Photo: Adriano Almeida/SUMAÚMA

A nun who stood and fought — When the missionary Dorothy Stang arrived in the region in 1982, three years before the end of the dictatorship, murders committed by the hired guns of the land grabbers and loggers were commonplace. She told Dom Erwin Kräutler, the then Bishop of Xingu, that she had come to work “among the poorest of the poor.” The bishop, who had already received death threats for his passionate defense of human rights, warned her: “You won’t be able to take this. You’re from the USA, with all its comforts. You won’t last here.” “Just leave me to it,” Dorothy replied.

She fought among the poorest of the poor until the day she was murdered. She and other missionaries worked hard to bring farmers together, and to help them work collectively, creating spaces for coexistence, the community organization of agricultural production, and income generation. The few schools in the area increased in quantity and quality. The collective mindset encouraged by Dorothy Stang created a context of prosperity that was part of a partnership with the forest. At the same time, however, it provoked the hatred of landowners, land grabbers and loggers who saw missionary work as an obstacle to cutting down the forest.

Magela Filho stood alongside her. He had grown up working in his family’s fields, studied, worked as a miner for a time, performed his military service, and even attended a Catholic seminary, before giving up the priesthood. Later he did various types of odd jobs to survive, before finally qualifying as an agricultural technician, marrying Elinete and joining the fight alongside Dorothy. When paying tribute to the missionary, the couples’ choked voices and tears reveal the strength of their feelings towards her.

On one occasion, when traveling the difficult roads of the Trans-Amazonian region on a motorcycle, Magela Filho suffered an accident and fractured both femurs. The couple had a small daughter, and Elinete had to go to hospital with her husband. “Sister Dorothy helped us so much, she got a twin-engine plane to bring us from Altamira to Belém. I will never forget that day my daughter was in her care. She was part of my family, at all times, in joys and difficulties,” says Elinete.

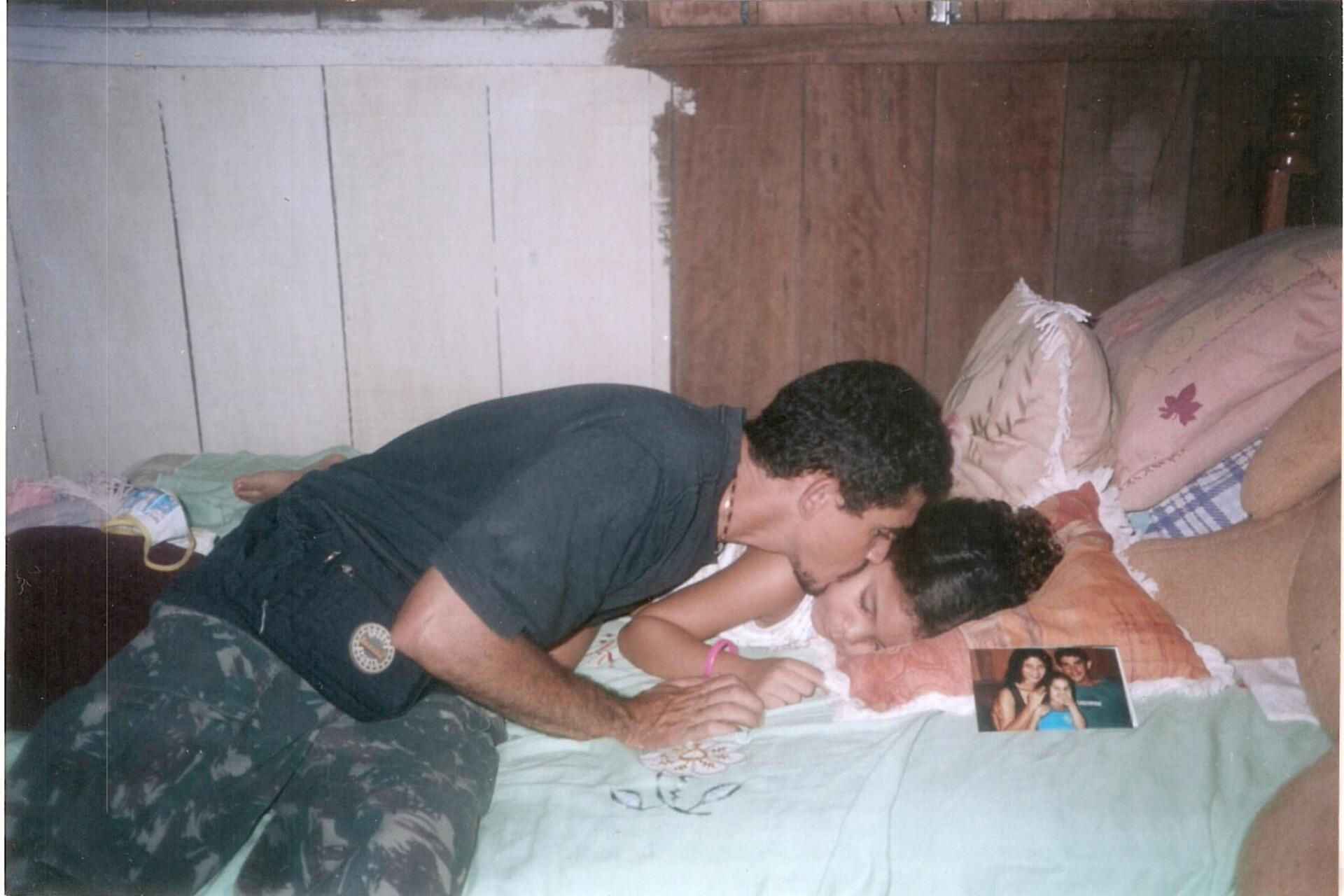

Leaving for a safer hiding place far from Anapu, Magela Filho says goodbye to his daughter Jhorrana. The two would only meet again months later. Photo: Geraldo Magela Filho personal archive

Stang’s murder, and the birth of Gaspar — On the day of the missionary’s murder, Magela Filho was riding his motorbike to the Esperança Sustainable Development Project, where he was to meet with social movement groups. On arrival, he was told the news and warned not to approach the crime scene, as the atmosphere was tense and there were fears other acts of violence would follow. He took cover in a hut at the side of the road until he saw the car transporting Dorothy’s body to Anapu approaching, and decided to follow the convoy on his motorbike. When he reached the police station that night, he reported the murder.

From that moment on, he devoted all his energy to cooperating with the investigations and helping to find the perpetrators of the crime, and those who had planned it. It was the first term of the presidency of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, and little had changed in Anapu, a territory dominated by land grabbers and their hired gunmen. At the request of the Pará branch of the Brazilian Bar Association and the Brazilian Attorney General’s Office, a federal investigation was launched.

The then president of the Bar Association’s Human Rights Commission, lawyer Mary Cohen, was assigned to oversee the investigations into the murders of Dorothy Stang and Alberto Xavier Leal, or Cabeludo. “There was a strong commitment from the local police to the loggers and ranchers. Geraldo Magela Filho played a very important role. He put the main players at the center of the investigation. Before that, they hadn’t been part of it, only the middlemen and the gunmen. After his testimony, those behind the murders were included,” says Cohen.

Magela Filho also joined Army and Federal Police search parties in the hunt for the killers and those who had ordered the crime. He knew the geography of the region intimately, and had a map of the Trans-Amazonian highway at his fingertips and in his photographic memory. “When Sister Dorothy Stang arrived, the first task she gave me was to draw a map of the territory,” he recalls, revealing the cartographic record he kept as a remembrance, along with photographs, cards, notes and other documents from the time.

Magela Filho not only collaborated with the investigations but also reported the failings of the local police authorities. His help was essential to the eventual locating of the gunman Rayfran das Neves Sales – according to Geraldo, he was the first to report Sales’ whereabouts to the Federal Police and Army, who carried out the arrest.

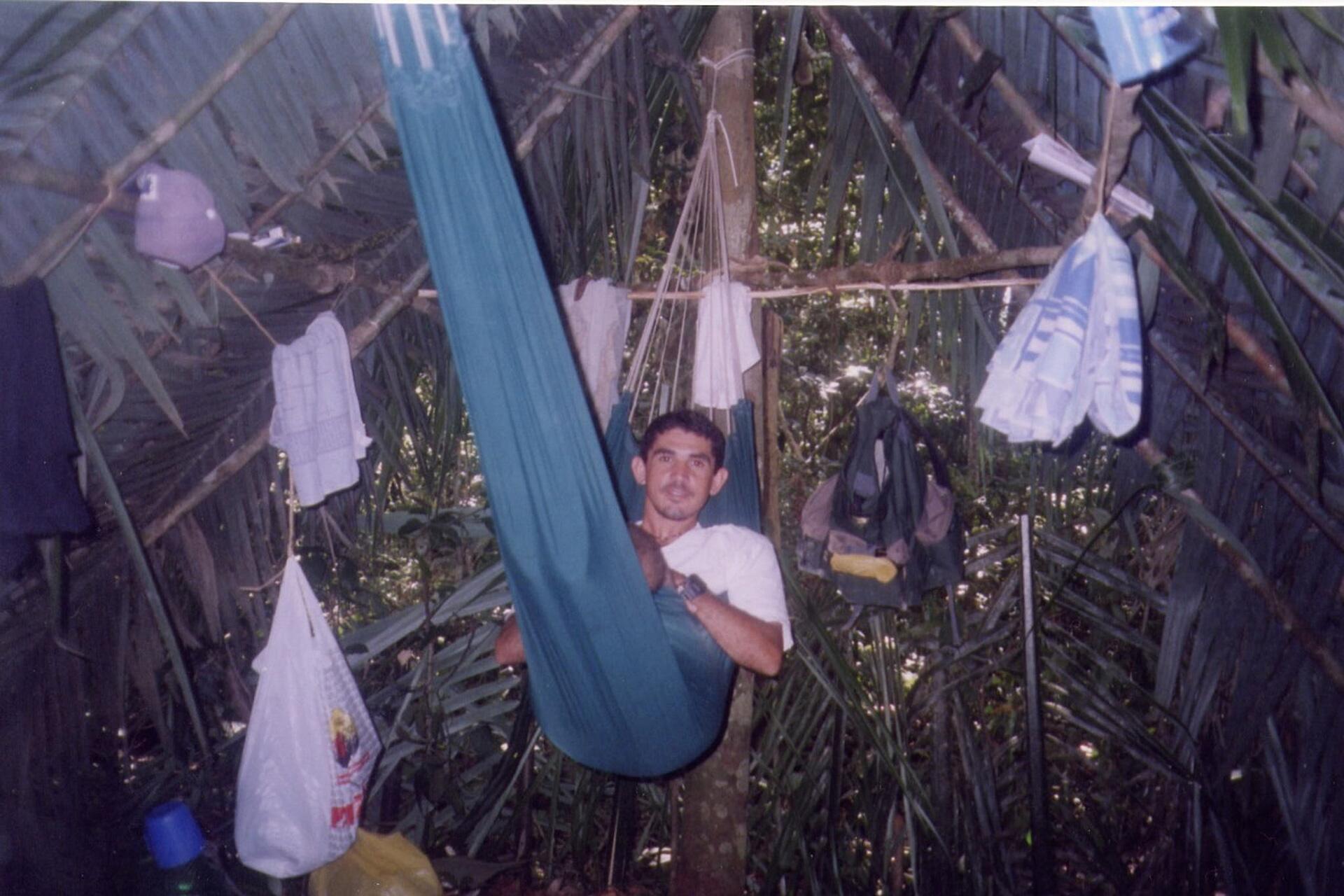

Three months after Dorothy Stang’s death, when Magela Filho was still in Anapu, he discovered a warrant for his preventative arrest had been issued. “It was the saddest day of my life,” says his father. Magela Filho fled, first to the Virola Jatobá Sustainable Development Project, where he hid for a month. Then, late one night, he camped in the forest at the bottom of his patch of land, before being warned by friends and social movement colleagues to leave Anapu. “He was already condemned. They were going to kill him before the legal process got started,” says Sister Jane Dwyer.

His escape route planned, he left his hideout for the town of Senador José Porfírio, 92,5 miles (149 km) away. He then took a speedboat to Porto de Moz. From there, he traveled ten hours by boat to the lowland region of Cupari, where he remained for three months. At the time, only satellite phone communication was available and calls were very expensive. He lived with the constant fear of being captured, and his wife visited him only once.

Magela Filho then decided to go to Belém, against the advice of the friends who were protecting him. To reach the capital of Pará, he needed to go back to Porto de Moz before traveling on to Gurupá. And it was there, when buying his ticket and afraid of being identified, he adopted the name José Gaspar da Silva. There, his clandestine identity of “Gaspar” was born, a name still remembered by his relatives and some of his friends. “My mother calls me by that name every now and again,” he says.

In Belém, he was welcomed by friends, and moved between several houses, always in hiding. He hoped to return to Anapu throughout his time on the run, but the open arrest warrant remained, both a threat and a psychological torture. If he couldn’t go back, he had to move on. And Gaspar went with him.

Elinete has returned to teaching, but will never forget Christmas in 2005, when she received a letter from her husband asking her to leave Anapu and live with him in Fortaleza. ‘I left with just a bag and a cardboard box,’ she remembers. Photo: Adriano Almeida/Sumaúma

Gaspar the traveling salesman — The solidarity of friends and social movements was essential to protect Gaspar. Unable to go out into the street, peeking at the outside world through the cracks in the gates and windows of the places where he stayed, most of his time was spent listening to music and reading books such as The Open Veins of Latin America, by Eduardo Galeano, as well as The Life and Death of Leon Trotsky, by Victor Serge, and the biographies of Ernesto “Che” Guevara and Simon Bolívar.

Amidst the solitude of those long days, he started smoking, let his hair grow long and decided to look for work. The long beard also helped mask his identity. Only once did he leave the house – when friends took him to an alternative bar in Belém, wearing a curly black wig and hippy-style clothes, giving Gaspar a chilled-out look.

Despite being told by friends he was relatively safe in Belém, he could no longer stand the confinement. In the Christmas week of 2005 he was taken to Capanema, in Pará, and from there took the bus to Fortaleza. “I didn’t want to be a weight, burden or responsibility for anyone, so I made the decision to leave,” he says.

That was when Elinette received a letter from her husband telling her to leave Anapu and come and live with him in Fortaleza. “I’ll never forget that day, when I had to leave behind the entire life we had built together: the house, the things we produced, my job as a teacher… My head was spinning. I left everything behind. I left my house in Anapu with just a bag and a cardboard box with some essential items,” she recalls.

Accustomed to rural life, where they could grow plants, breed animals, and have lots of space and the forest, Gaspar and Elinete started their life in hiding together in a studio apartment in Fortaleza. They looked for jobs, without success, until 2006. In early 2007, an acquaintance, the son of farmers from the Trans-Amazonian highway region, who worked for a sandal production company, got in touch and offered Magela Filho a job in the state of Maranhão.

Two years after the killing of Dorothy Stang, at the beginning of Lula’s second term as president, but still without any promise of justice, Gaspar began a life as a traveling salesman on the route to Imperatriz and neighboring towns.

Magela Filho uses a truck, bought on a long payment plan, in his job as a traveling salesman. His main customers are agricultural industry businesspeople. Photo: Adriano Almeida/Sumaúma

From agrarian reform activist to salesman — Life in the new city began in another studio apartment. Fearing capture, as the arrest warrant against him was still in effect, Gaspar would get nervous whenever he approached police checkpoints. When he arrived in Imperatriz, he switched his route to Araguaína, in Tocantins, but sales were low. He went through hard times, sold his motorcycle, bought a used truck on a lengthy installment plan and entered the street vendor business, selling dish towels, rubber seals for pressure cookers and other small household items that he added to the sale of sandals.

In 2010, through another contact, he became a boot salesman. During that time, he started building his own house, a major step for someone on the run using a false name. “It was a very important moment for me. We bought the land and started building, then moved in when there was still no plaster or floor. We were doing it little by little,” he says. In 2017, he risked using the name Geraldo Magela de Almeida Filho when he needed to register his own company to issue invoices.

Elinete celebrates two achievements: their new house, built through hard work, and, since November, the acquittal of her husband Geraldo Magela Filho. Photo: Adriano Almeida/SUMAÚMA

The truck in which he travels the roads of Maranhão and Tocantins has an inscription on the bumper: 12.02.2005, the day Dorothy Stang died. His main customers are traders in the agribusiness sector of Amazon towns and cities, the vast majority of whom are supporters of the extreme right, nationalists and “patriots”, and enthusiastic voters of Jair Bolsonaro. To avoid awkward questions, Magela Filho put a little Brazilian flag on his truck during the elections. “I only have two Lula-voting customers,” he says.

At home, the conversation is more progressive. Over coffee, Geraldo Magela, father (94 years old) and son (51 years old) discuss the war in Ukraine and related topics. The talk ranges far and wide, and Geraldo Magela Senior concludes that Brazil has only had two great presidents: “Getúlio Vargas and Lula, both fathers of the poor.”

Elinete Almeida has rebuilt her life as a teacher in Imperatriz, and is celebrating two achievements: the new house, built from hard work, and, since November, her husband’s acquittal. The family were delighted. “His freedom at the trial was the greatest joy of my life,” his father says.,kkk

On the bumper of his truck, Magela Filho has inscribed the date of Dorothy Stang’s death: 12.02.2005. He travels the highways of the Amazon selling country products to local businesses. Photo: Adriano Almeida/SUMAÚMA. Note: for reasons of security, his registration number has been removed by SUMAÚMA

Missing an ending — The trial and unanimous acquittal closed a chapter that no one would want to go through. Asked if he would do it all over again, however, Magela Filho doesn’t hesitate. “Yes,” he says. “Working with Dorothy Stang was a source of satisfaction, joy and pleasure. We did it for love. The death of the forest could be the collapse of the planet. That was the message she brought: valuing people who have this philosophy, the traditional populations who are not greedy to get rich at the expense of devastation. This is a lesson we will carry with us for the rest of our lives.”

Sitting on the porch of his home, surrounded by remembrances of Anapu, Magela Filho wears a necklace and bracelet from the Gavião indigenous people. On his constant travels through Amarante, a town on his sales route 70 miles (112 km) from Imperatriz, he made friends with a family and started to visit their village. Living together is a way of reconnecting with native peoples. “I miss the days when I lived in Anapu. For me, indigenous people are the guardians of the environment, that’s why I use their decorations. It isn’t gold, but something original, the result of hard work and knowledge,” he explains.

The murder of farmer Alberto Xavier Filho, or Cabeludo, remains unpunished. The two most firmly believed theories among members of the region’s social movements are that he was killed because he was a witness, or to incriminate Magela Filho. “Cabeludo’s family was destroyed. His wife and children are struggling,” says Sister Jane.

Anapu it is more violent today than in Dorothy Stang’s time. The international outcry over the murder of the US missionary meant the State strengthened its presence in the region, making criminal activities more difficult. Not that this brought an end to the illegal mining and commercial exploitation of wood – simply that the region’s crime bosses knew that further killing would damage business, and bring the State closer to them. As a result, there wasn’t a single murder over land conflicts in Anapu between 2006 and 2014. With the weakening of Dilma Rousseff’s Workers’ Party government during its second term, however, followed by the impeachment that put Michel Temer in power, the killings returned. The predatory exploitation of the forest was once again given the green light, a shift that culminated in Jair Bolsonaro’s deliberate incentivizing of the destruction of the Amazon. Between 2015, Rousseff’s last year in power, and 2019, Bolsonaro’ first year as president, there were 19 deaths, according to the Pastoral Land Commission.

During the government of Brazil’s right-wing extremist Jair Bolsonaro, Plot 96, in the area of Gleba Bacajá, in Anapu, became the principal target of land grabbers in the region, while this year families have been taken hostage by gunmen, and had their homes and the community school set on fire. Plots 96 and 97 were even named Settlement Dorothy Stang, until pressure from land grabbers blocked the process at the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform. Since Bolsonaro’s first year as president, camponese leader Erasmo Theofilo and his partner, the quilombola Natalha Theofilo, and their four small children, have already had to flee six times to save their lives.

While Magela Filho was acquitted, the Theofilo family have become exiles within their own country, made refugees to escape death. It is likely they will remain in exile until Lula takes office in January – and even then there is no guarantee of safety in Anapu. All the leaders in the region who live under threat fear an explosion of violence before the end of the year. The Brazil that forced Magela Filho to become Gaspar persists. And it’s worse now than then.

Translated by James Young