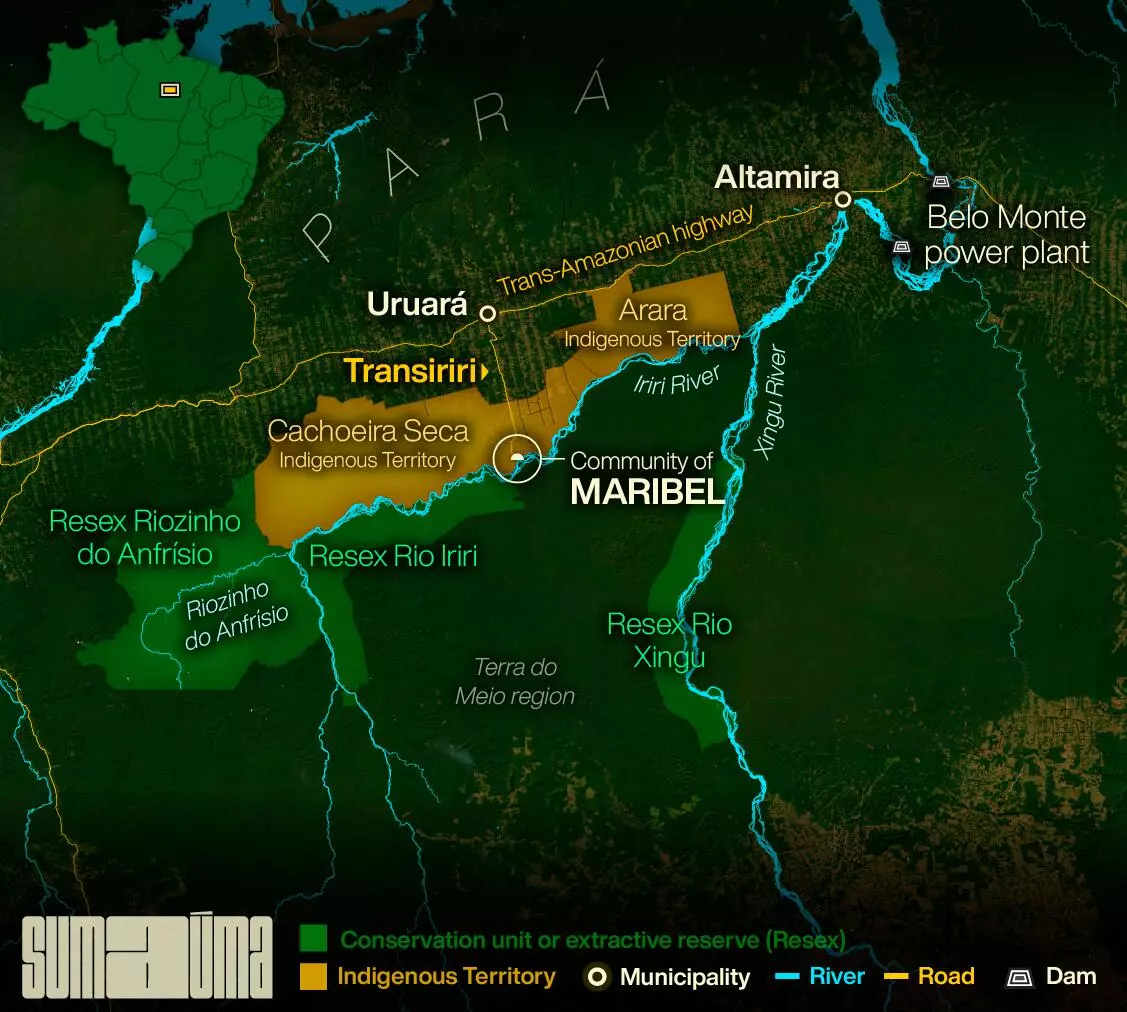

When they told him the land where he raised his family was Indigenous territory, Josamir Bacabeira didn’t believe it. He had found no trace of previous inhabitants when he planted his first Brazil nut trees in Maribel, a community of people who live off fishing and the artisanal extraction of forest resources on the banks of the Iriri River, in Pará state. “We were sure it was fake news. Something they made up for no reason, something time made up,” he says, referring to 1985, when the federal government designated the area as the future Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory—and the community where Josamir’s family had lived since the 1940s fell inside its borders. While the government’s decision was the first step toward guaranteeing the Arara people their rights, it put a traditional community of more than 55 families at risk of expulsion. “For beiradeiros [members of traditional forest communities living along rivers of the Amazon], there’s no land without a river. Can you imagine a fish living out of water?” says Josamir, a 55-year-old man with sun-weathered skin and traces of the Canela Indigenous people. Josamir, father of this article’s author, is afraid he may have to leave the land where he was born and raised.

During World War II (1939-1945), Josamir’s grandfather heeded an appeal by the Brazilian government and moved from his arid homeland in Ceará state to Pará. Under the federal project, he became a “rubber soldier,” the term used to describe the workers who left the poorest areas of the Brazilian Northeast and settled in the Amazon, where they extracted rubber for export to the United States and its allies for use in the war effort. In the planet’s largest tropical rainforest, Josamir Bacabeira’s ancestor put down roots, working the soil, building a house, and raising a family.

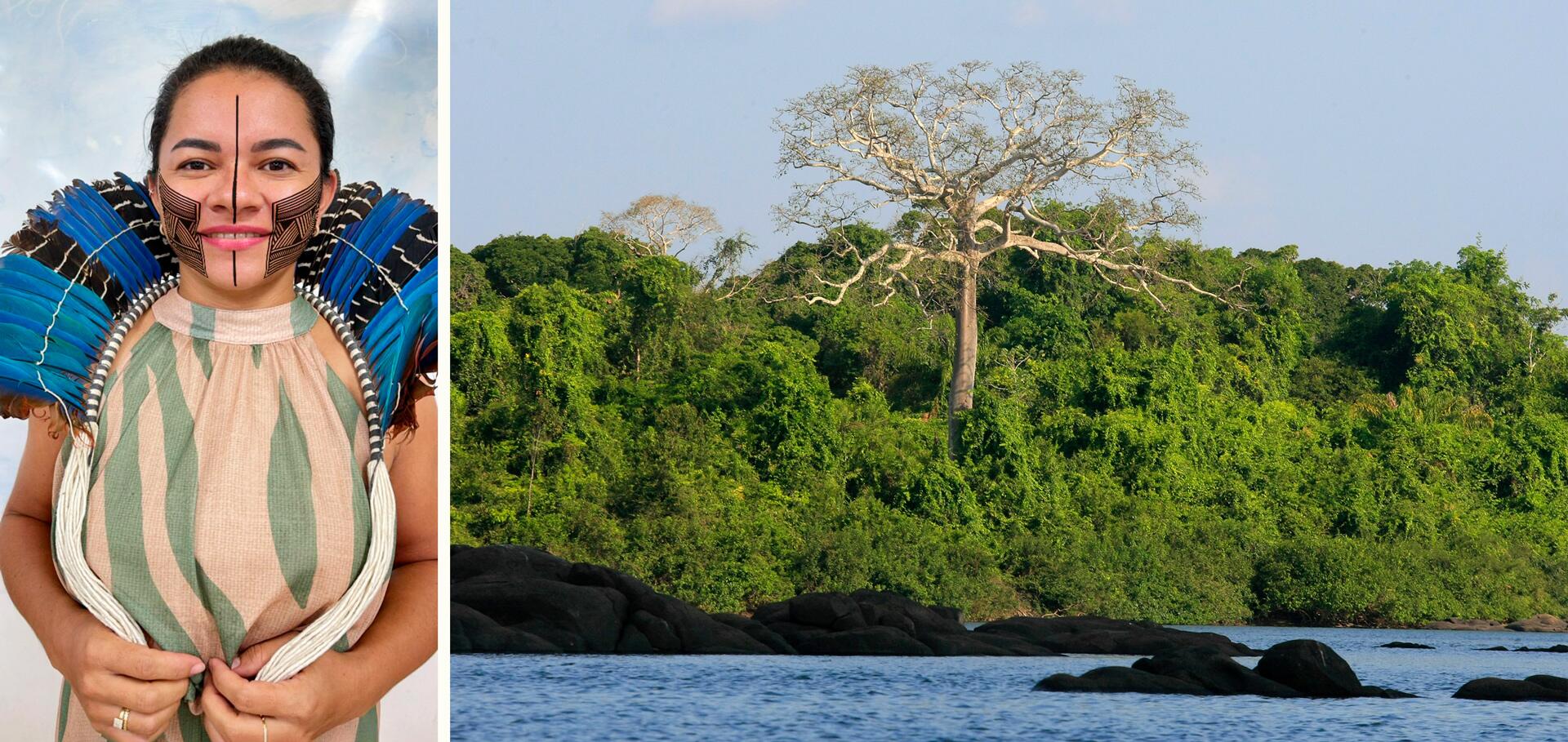

Born in Maribel, skipper Josamir Bacabeira fears he’ll die without knowing if his children and grandchildren can enjoy a childhood like his on this land. Photo: Soll/SUMAÚMA

The Arara—who Josamir came to know only later—had their first contact with non-Indigenous people around 1850. According to “Indigenous Peoples of Brazil,” a publication of the Socioenvironmental Institute, a reference to the Arara appears in official records in 1853 and one of their subgroups was mentioned in 1896 by the voyager Henri Coudreau, who undertook an expedition along the Xingu River.

In 1940, when the beiradeiro’s ancestors settled in the village now called Maribel, the Arara were thought to be extinct, which may be why Josamir Bacabeira was unaware of their existence. They were no longer seen after battles with other original peoples, such as the Kayapó and Juruna (Yudjá), and especially after massacres promoted by rubber bosses. But they reappeared when Brazil’s business-military dictatorship (1964-1985) built the Trans-Amazonian highway. The group that inhabits the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory was only contacted in the late 1980s and has suffered a series of abuses, culminating in the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant, which had a major impact on their way of life.

There is no doubt the Arara people have inhabited these lands for centuries, although official recognition of their territory came late. But when Josamir Bacabeira was born in the beiradeiro village, the Indigenous people had experienced multiple attacks and possibly made themselves invisible to save their lives. So in 2016, with several generations having lived on these lands, the family was shocked to find out the news from 1985 hadn’t been fake: Maribel was really inside the Indigenous territory.

This was when then-president Dilma Rousseff (Workers Party, 2011-2016) had ratified the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory, the final step in legally establishing these as the lands of the Arara people—leaving Maribel in limbo as a traditional Brazilian community now lying inside an Indigenous territory, its residents at risk of eviction under law. In addition to living with this threat, the beiradeiros of the Middle Xingu have also been neglected by federal policies. Because they are non-Indigenous inhabitants of an Indigenous territory, they are tossed back and forth like hot potatoes by federal bodies such as Brazil’s agency of Indigenous affairs Funai and the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, the agency in charge of conservation units.

“We live in constant worry. If the federal government would look into our origins, we wouldn’t have to leave this land, because we’re founders of these areas. I’ve told the folks at Funai [Indigenous affairs agency] that if they want to pull us out of here, they’ll also have to pull out the land that has died, where my mother and other family are buried,” says Josamir. Beiradeiro and motorized canoe pilot, Josamir was born and raised in the region of the Iriri River, a tributary of the Xingu, where he learned to survive by hunting, fishing, and extracting forest resources. He says he has been navigating the Xingu, Iriri, and Riozinho do Anfrísio rivers since he was 12. His mother, who according to Josamir was Indigenous, was born on the Iriri; when his ancestors reached these parts, she was already there. She died at the age of 98 and is buried in Maribel, along with Josamir’s other relatives.

Josamir’s greatest fear is that he will be expelled from the land he works. “When you take a fish out of a lake and throw it on dry ground, it dies. Because a fish, if thrown on dry land, dies of thirst. And us, if we’re thrown into some other corner, outside the river, we’ll die of thirst the same way. If they move us off the riverbanks and dump us in the middle of the woods; older people will die of sadness,” says Josamir, who knows the river’s regions like few others. His biggest dream is to raise his children and grandchildren on the same land where his parents raised him, but he worries he could die without knowing for certain whether this will happen.

In Riozinho do Anfrísio during the 2023 drought, beiradeiros (traditional riverside dwellers) had to push their boats to reach Maribel, where they could access Altamira by land. Photos: Renata Carneiro

If the menace of eviction has haunted these beiradeiros since the 1980s, the situation worsened last year. On September 25, 2023, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security published an administrative ruling in its official gazette that brought despair to Maribel. The document authorized the National Public Security Force to provide backup to the Indigenous agency Funai “with services indispensable to preserving the public order” within the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory.

The beiradeiros interpreted this document as an official move to expel them, but Melania Gonçalves, president of the Iriri River-Maribel Extractive Association, obtained information about the matter that reassured them. According to Melania, a staff member at Funai in Altamira said the National Security Force was not being called in to remove people from the territory but to help build a base there. The base, one of the conditions demanded by Funai as a counterpart to the construction of Belo Monte, a hydroelectric power plant inaugurated in 2016, is meant to protect Arara lands, among the most heavily deforested Indigenous territories in Brazil. Residents of Maribel breathed a sigh of relief—but not for long since the threat of expulsion still looms over them.

When contacted by SUMAÚMA, Funai said that in 2023 it had “requested credit to pay compensation to the non-Indigenous people affected by the legal recognition of the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory” as part of the federal budget for 2024. The agency, however, did not confirm whether Congress had approved the credit. It also said it had conducted studies in the region between 2011 and 2016 and “identified 1,173 non-Indigenous settlements eligible for compensation for property improvements.” Further, according to Funai, the agency submitted an official letter to the Chico Mendes Institute “in order to strengthen inter-institutional dialogue, with a view to relocating these people to another extractive reserve.” Funai is also asking Brazil’s agrarian reform authority INCRA to help resettle the beneficiaries of agrarian reform. In a note sent to SUMAÚMA, the agency said “the Arara of Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory are considered recently contacted Indigenous and so are particularly vulnerable.”

Rubber tapper José Moreira da Silva, nicknamed Simbereba, keeps the family tradition as a descendant of a “rubber soldier.” Photo: Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA

In 2012, Funai delineated the criteria for distinguishing “good faith” occupants, who have the right to compensation for property improvements, from “bad faith” occupants, who simply have to leave. As the agency defines it, a “bad faith” occupant is someone who “knew or could have known that it was Indigenous territory” but nonetheless settled there, who committed violence during the act of invasion, or who causes environmental destruction.

“The love we feel for this land where we live can’t be repaid at any price,” says 56-year-old Melania, who was born on the banks of the Iriri River and devotes herself to defending her community’s rights. “Our life story is here, our childhood memories. We have families who have died and are buried here. Sometimes we hear a bird singing, and we remember when we used to walk the rubber tree trail with our father or mother. There’s no amount of money that will erase all this, pay for it, replace all this love, all our living experience with this land. This land is much more than money to us,” says the association leader, whose father also came to the Amazon from Ceará as a rubber soldier, like so many others in Maribel.

With sad eyes, Melania says if they’re evicted, it will be hard not only for those in Maribel but also for others in Terra do Meio—a mosaic of protected areas between the Xingu and Iriri rivers—and for the Indigenous of Cachoeira Seca themselves. This is because the community of Maribel—originally settled by two rubber soldier families, the Bacabeiras and the Semberebas, in the 1940s—is the only place in the region with road access to the municipality of Uruará, located along the Trans-Amazonian highway.

A lack of public policies affects residents of Maribel. Beiradeiro here are carrying a man stung by a scorpion to a place where he can get help. Photos: Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA (Melania) & Paulo Sérgio

In the Amazon winter, people living upstream from Maribel depend on the Iriri and Xingu rivers for their livelihoods and transportation. In the dryer summer period, from June to December, the rivers are too low for vessels to reach Altamira, the nearest major city. As the only place from which community products like fish, Brazil nuts, babassu flour, and copaiba oil can reach market, Maribel is especially busy at this time of year and even provides logistical support to patients in need of medical services. While the road is helpful to residents of Terra do Meio, it also serves landgrabbers and illegal loggers.

Melania says she has often been woken up in the middle of the night and asked to help out residents of other beiradeiro communities and even Indigenous people from the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory. “If the Indigenous had to depend on Funai to survive, they would have died. One night I had to rush an Indigenous man to the hospital in Uruará. Thank God he didn’t die.”

‘For us, public policies are like a dog watching a chicken roast—on TV’

Because the Maribel beiradeiros live inside an Indigenous territory but aren’t considered Indigenous, they don’t benefit from public policies aimed at traditional populations, and neither the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation nor the Indigenous authority Funai usually provide services to the community’s residents. The only type of assistance comes from nongovernmental organizations, such as the Socioenvironmental Institute and community associations in Terra do Meio.

Beiradeiros live by planting, hunting, and fishing while maintaining a traditional way of life and preserving the forest. Photos: Joelmir Silva (fishers & fish) & Paulo Santos (river)/SUMAÚMA

Since construction of the Belo Monte hydropower plant began in 2011, Maribel has been excluded from government benefits at least twice. The first time involved a licensing stipulation defined by Brazil’s environmental authority Ibama in 2015, requiring the hydropower project to compensate Terra do Meio families for the negative impact of dam construction on the region’s fish population. Prior to 2022, Maribel beiradeiros had been part of the negotiations. That year, however, the Chico Mendes Institute took over the process and Maribel was crossed off the list of future beneficiaries, precisely because it now lies inside an Indigenous territory.

Francinaldo Lima, a biologist and advisor to community associations in Terra do Meio, says he has always included residents of Maribel, Terra do Meio Ecological Station, and Serra do Pardo National Park on the list of future beneficiaries. But when the Chico Mendes Institute took charge of the process in 2022, it ruled that the benefit would apply only to families within the federally ratified Riozinho, Xingu, and Iriri extractive reserves. Francinaldo laments the decision. “I was in a really delicate position because, directly or indirectly, it looked like I was complicit in excluding a community I know to be a traditional one,” he says, stressing that today his “hands are tied.” According to the current list, 330 families from the extractive reserves are due to receive compensation but Norte Energia, the consortium that owns the concession for Belo Monte, has yet to pay.

Maribel fishers say that before Belo Monte, they didn’t have to travel very far from their communities to fish and so they spent less on fuel. They feel the arrival of “development” has cost them.

Damásio is a short man with a firm, honest look who has known the region’s rivers and fishing spots since childhood. He says they used to catch tons of fish in Maribel, but since the dam was built, they’ve had to travel farther to get their staple food. Many have turned to illegal activities to make a living. In his words, “as time went by, our river turned black” and the bottom can no longer be seen through once crystal-clear waters. “Before [the Belo Monte dam], everything was easier for us. But there was this big change, this impact, and we weren’t recognized as fishermen. I’ve had my fisherman’s Work Card since 2013, but I’ve never received any subsidies,” Damásio says. “The whole time, they’ve been dragging their heels, and we’ve never received anything. And things got tough.”

Natália Assunção, a beiradeira who monitors the daily fish catch, also reports problems. “Fishermen face the challenge of having to go farther and farther away to fish, but there’s also the issue of price. According to them, fish are fetching the same price, but their costs go up every day,” she says.

When contacted by SUMAÚMA, the environmental agency Ibama said the “community of Maribel, located upstream from the plant’s main reservoir, is not is not influenced by the reservoir.” As to the residents of Terra do Meio extractive reserves, the agency said Norte Energia and environmental bodies have not reached a consensus about the impacts of the hydroplant but that discussions are advancing. “ICMBio [Chico Mendes Institute] has concluded that the way of life and fishing activities of residents of [these extractive reserves] were impacted by the construction and operation of the Belo Monte power plant, while Norte Energia claims these impacts cannot be attributed to the plant.” In light of this dispute, Norte Energia filed an appeal, which was rejected by the environmental authority in 2020. Negotiations have since resumed.

When questioned about the matter via email, Norte Energia declined to comment.

Aerial view of the port of Maribel, on the banks of the Iriri, in the region of Altamira. Photo: Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA

The other situation in which the residents of Maribel were excluded was the “Light for All” program. In 2017 the Chico Mendes Institute did a preliminary study for the electrification project. “But since the institute limits itself to conservation units, which are its responsibility, the survey was only conducted [within them],” says the advisor Francinaldo Lima. Under the program, solar energy panels would be installed in the Xingu, Iriri, and Riozinho do Anfrísio extractive reserves. Similar to what happened with the requirement to pay compensation for fishing losses, Maribel was left out once again. And as in the first case, nothing has come of the plans yet.

In a note sent to SUMAÚMA, the Ministry of Mines and Energy said that according to the law, Funai must issue prior authorization before any electrical services are provided to communities inside Indigenous territories. The ministry also said 369 customers will be served within four conservation units in Terra do Meio: Terra do Meio Ecological Station and the Iriri, Xingu, and Riozinho do Anfrísio extractive reserves. “The aforementioned communities are being included in the current Works Program, following talks between the MME [Ministry of Mines and Energy] and ICMBio [Chico Mendes Institute].”

Equatorial Pará, the state energy distribution company, said that “for the community of Maribel to be served by the project, the MME [Ministry of Mines and Energy] must prioritize it.” It also said that if these families are approved as beneficiaries, authorization would be needed “from Ibama [the environmental agency] and Funai before the project is executed, since future connections would be on Indigenous lands.”

The Chico Mendes Institute was contacted 11 times by email and telephone but did not reply.

In addition to the compensation paid for the decreased fish population and the solar panel program, residents of Maribel say they have been sidelined from other public policies. “The other day, I saw a healthcare team passing my port [Solidade, which is part of Maribel]. They were doing registrations, something called the ‘citizen’s desk,’ but they didn’t include us, just the folks in the extractive reserves. They didn’t even have any vaccines for us. They always say the program isn’t for us. Sometimes we get the leftovers,” says Lúcia Helena, who works with forest medicinals. Lúcia Helena is a strong, wise woman of 66 who is saddened by the government neglect. “Does Funai think we’re landgrabbers? Sometimes I don’t even know who we really are, because it’s just too much,” she says. Lúcia Helena describes the people of Maribel as “neither invaders nor Indigenous.”

Lucia Helena, longtime resident of Maribel, makes forest medicinals that are used to heal her people. Photos: Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA

Association president Melania Gonçalves isn’t satisfied: “It upsets me, seeing these rights violated, knowing the only lights we have today are battery-powered lanterns or oil lamps. It’s like a dog watching a chicken roast on a spit on TV—he can’t eat it. That’s how government policies work for us,” the leader says.

Living in the worst of all worlds

Maurício Torres, a professor at the Federal University of Pará, worked in Maribel from 2007 to 2014. He opposes the idea of reducing Indigenous territories in Brazil but, on the other hand, understands that Maribel’s situation is unique. “Today, you [extractive producers of Maribel] and landgrabbers alike are treated like invaders, but you’re not. You’re the victims of inaction on the part of the State. The State doesn’t act and leaves you in the worst of all worlds: it doesn’t relocate you and doesn’t let you stay on your land,” the researcher says. He is in favor of relocating Maribel residents and compensating them for the time they lived in this territory and for their property improvements. But the beiradeiros heard by SUMAÚMA don’t want to be relocated or paid compensation.

Maurício points out that Maribel beiradeiros have rights. “In the first place, not to be treated like invaders. In the second place, to have your situation legalized,” he says. An alternative, according to Maurício, would be an agreement with the government that guarantees the community a provisional land document until a decision is made on relocation and compensation.

A number of specialists heard by SUMAÚMA were in favor of establishing this type of agreement with the government. The anthropologist Márnio Teixeira-Pinto has been researching the Arara people since the 1980s and was involved in the process of officially recognizing the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory in 1994. He spent months talking to beiradeiros and Indigenous in the region and has always believed the people of Maribel could remain there, under an agreement. “[The idea has always been that] these communities should have the right to remain, under conduct agreements for example, as long as their lifestyle was traditional. This means preventing the continuation of travessões [illegal local roads that traverse protected areas, specifically, the Transiriri, which links Mirabel to Uruará]. The anthropologist, who is a researcher and professor at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, says the Arara and Cachoeira Seca Indigenous territories were always intended to be continuous. Today, the Transiriri road out of Maribel divides the two territories and, according to Márnio, hampers the movement of the Arara between them. “The Transiriri has always represented an environmental and social threat to Indigenous life in the long term,” Márnio says.

Márnio recalls the countless hardships experienced by the Arara people both before and after their first contact with the non-Indigenous, between 1981 and 1987. “They still live in a climate of great conflict, threatened by various waves of invasions, land grabbing, and timber theft. There are Indigenous people in Laranjal village with bullet marks in their backs,” he says. Even today, illegal invaders are destroying the forest there. As part of a process related to the construction of the Belo Monte hydropower plant, Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory was a deforestation leader in 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2020, according to data from the Socioenvironmental Institute drawn from the National Institute for Space Research’s Amazon Deforestation Monitoring Project.

Beiradeiros in Maribel send their products to market on the Transiriri (left), a road also used by landgrabbers and illegal loggers. Photos: Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA

The local road mentioned by Márnio is currently the subject of a political dispute. During election season, there are those who take advantage of the land issue to defend the so-called historic cut-off point, that is, the argument that the only Indigenous people with land rights are those who effectively occupied their territory in 1988, when Brazil ratified its newest Constitution.There are also politicians who advocate the reduction of Indigenous territories, using current occupants to ground this unconstitutional narrative and promising to cede them land. This is the position endorsed by both Senator Zequinha Marinho (We Can-PA) and Uruará municipal councilor Matheus Sousa (Liberal Party-PA), who were at Kilometer 185 South of the Transiriri road, inside Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory, on February 10. In a video posted on his social networks after the visit, the senator called for a new anthropological study “to determine that there are actually no traces of Indians [sic] who have lived there, either in the present or distant past.” This narrative is meant to appeal to people living along the Transiriri and to those who would like to see Indigenous territories reduced—a position championed by far-right former president Jair Bolsonaro and his supporters.

When contacted, Senator Zequinha Marinho said, “My fight is for the families of Pará who face the threat of losing their land. The rural farmers in the region have occupied the area for decades.” Over the course of three days, SUMAÚMA called and sent WhatsApp and email messages to municipal councilor Matheus Sousa through the communication channels of the Uruará Municipal Chambers and the councilor’s phone. The councilor did not respond to requests for an interview.

Representatives of the Arara people were contacted but, for reasons of security, preferred not to comment.

A monkey and Rita Mariah, a beiradeira whose face has been painted by the Arara, have fun during a community assembly. Photo: Francinaldo Lima

According to association president Melania, the Indigenous of Cachoeira Seca and the longtime beiradeiros of Maribel currently enjoy a relationship of mutual respect, and land issues have not divided them. “I don’t see the Arara as enemies. There aren’t any quarrels, conflicts, or issues between us. On the contrary, we’re really close. We have great respect for them, and them for us. The land issue hasn’t damaged this friendship and the respect we have for each other,” she says.

While nothing gets done and government agencies continue to play their game of hot potato with the beiradeiros of Maribel, young people in the community experience the anguish and anxiety of not being sure if they can remain on the land. Gisele Cardonha, activist, granddaughter of an Indigenous couple, and daughter of a rubber tapper, was born and raised in Maribel. This young forest-maker and mother of twins is studying ethnodevelopment at the Federal University of Pará. She hopes in her heart she’ll be able to give her children the same childhood her ancestors gave her. When SUMAÚMA asked Gisele for an interview, she replied with this poem:

What if I leave here?

I live in the community of Maribel

on Iriri River, and sometimes I find myself wondering

What if I leave here?Here we have our beautiful river,

where we can swim and fish.

It gives us fun, it gives us food.

Any time of day,

we can go paddle.Have you ever thought about the art

of balancing in a canoe?

Not everyone can,

but this art is known to beiradeiros.What if I leave here?

What about my friends and relatives?

Will we be together,

or will they separate us too?Belo Monte has shaped us,

shaped uncertainty,

the uncertainty of losing the land who raised me

and the river where my children might no longer swim.

The white clay embankment

they’ll no longer slide down.Oh, childhood, such a shame,

the uncertainty of not seeing a new cycle begin again.

What if I leave here?

Will they give me another Iriri?

What if I leave here? What if I leave here?

‘Here we have our beautiful river where we can swim and fish. Any time of day, we can go paddle,’ Gisele Cardonha says in a poem. Photos: Joelmir Silva (Gisele) & Paulo Santos/SUMAÚMA

Joelmir Silva is the great-grandson of a “rubber soldier,” grandson of an Indigenous woman, and son of a rubber tapper. He was born and grew up in Maribel, a traditional Amazon community located within an Indigenous territory, and therefore runs the risk of being evicted from his land. Now home to 55 families, Maribel was built in the 1940s by migrants from the Brazilian Northeast, drawn by the government to the planet’s largest tropical rainforest to work as rubber soldiers, as they are called. These men tapped rubber for export to the United States, where it was used in vehicles and tanks during World War II. In 2016, the Brazilian government legally recognized the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory as belonging to the Arara people, and the community of Maribel ended up inside these protected lands, where they no longer have the legal right to reside.

Joelmir became literate at the age of 17 and now participates in Mycelium, SUMAÚMA’s Forest-Journalist Co-Training Program. He is an elementary school teacher in Terra do Meio and is studying for a bachelor’s degree in ethnodevelopment at the Federal University of Pará, Altamira campus. As a beiradeiro—member of a community of traditional forest peoples in the Middle Xingu— Joelmir started the communication collective Voices of the Xingu, a space where forest-communicators take the reality and challenges of the Amazon to the rest of Brazil. The group, which includes both Indigenous and beiradeiros, uses such platforms as podcasts, videos, photographs, and amateur radio to show the world how life is lived in the many Amazons that exist and how traditional forest peoples relate to the forest and rivers. Because he defends the Amazon and maintains a traditional way of life in harmony with nature, Joelmir considers himself a forest-maker. Like the Yanomami, he believes his beiradeiro people hold up the sky.

***

The Mycelium-SUMAÚMA Forest-Journalist Co-Training Program began in May 2023. Fourteen young people from the Middle Xingu—four Indigenous youth, three youth from traditional forest communities, one from a quilombola community, one small-hold farmer, a fisherwoman, an Indigenous health nurse, and young people from urban communities in the city of Altamira—participate in gatherings in the forest and the city. The youth are guided by senior journalists at SUMAÚMA, known as “seed-mentors,” who are in turn guided by the youth, since co-training is an exchange. The seed-mentor of this special report on the dire situation of the Maribel community was Ana Magalhães. Joelmir Silva, beiradeiro and participant of the Mycelium program, offers an in-depth news story that encompasses diverse viewpoints and respects the rules of professional journalism, based on an exploration of the author’s own geopolitical and affective territory, making this narrative a testimonial as well.

Coordinated by Raquel Rosenberg, co-founder of Engajamundo, the teaching method used by Mycelium-SUMAÚMA, deliberately eschews any type of orthodoxy. Conceived by Eliane Brum (likewise responsible for supervision and content) and Jonathan Watts, the program maintains the rigor, responsibility, and accuracy of traditional journalism.

Micélio-SUMAÚMA also includes psychoanalyst Ilana Katz, providing care consulting, and producer Thiago de Sousa Leal. Mônica Abdalla is responsible for managing the Program’s finances, with administrative and financial assistant Marina Borges and financial consulting from Mariana Zahar. Micélio-SUMAÚMA receives funding from the Moore Foundation and the Google News Initiative.

Report and text: Joelmir Silva

Editing: Ana Magalhães and Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Célia Arruda

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Editorial workflow, copyediting and finishing: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum