For a child to vomit worms, their bodies have to be infested by so many parasites that their lungs are affected, their breath becomes short, their temperatures reach the level of a fever and they feel persistent intense pain. For a doctor with even rudimentary skills, Loeffler syndrome is easy to diagnose and treat with a course of pills. But in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, children have been dying with these symptoms in recent months because healthcare professionals cannot access their land due to criminal mining activity.

Add to this fatal cases of diarrhea and pneumonia, and at least nine children have died from treatable diseases since July in Brazil’s largest indigenous region, according to a report by Hutukara Yanomami Association, the main representative body of the ethnic group. They say this demonstrates how the area’s already fragile healthcare system has broken down under the assault of illegal miners, who criminally invade a territory that is officially under the protection of the state.

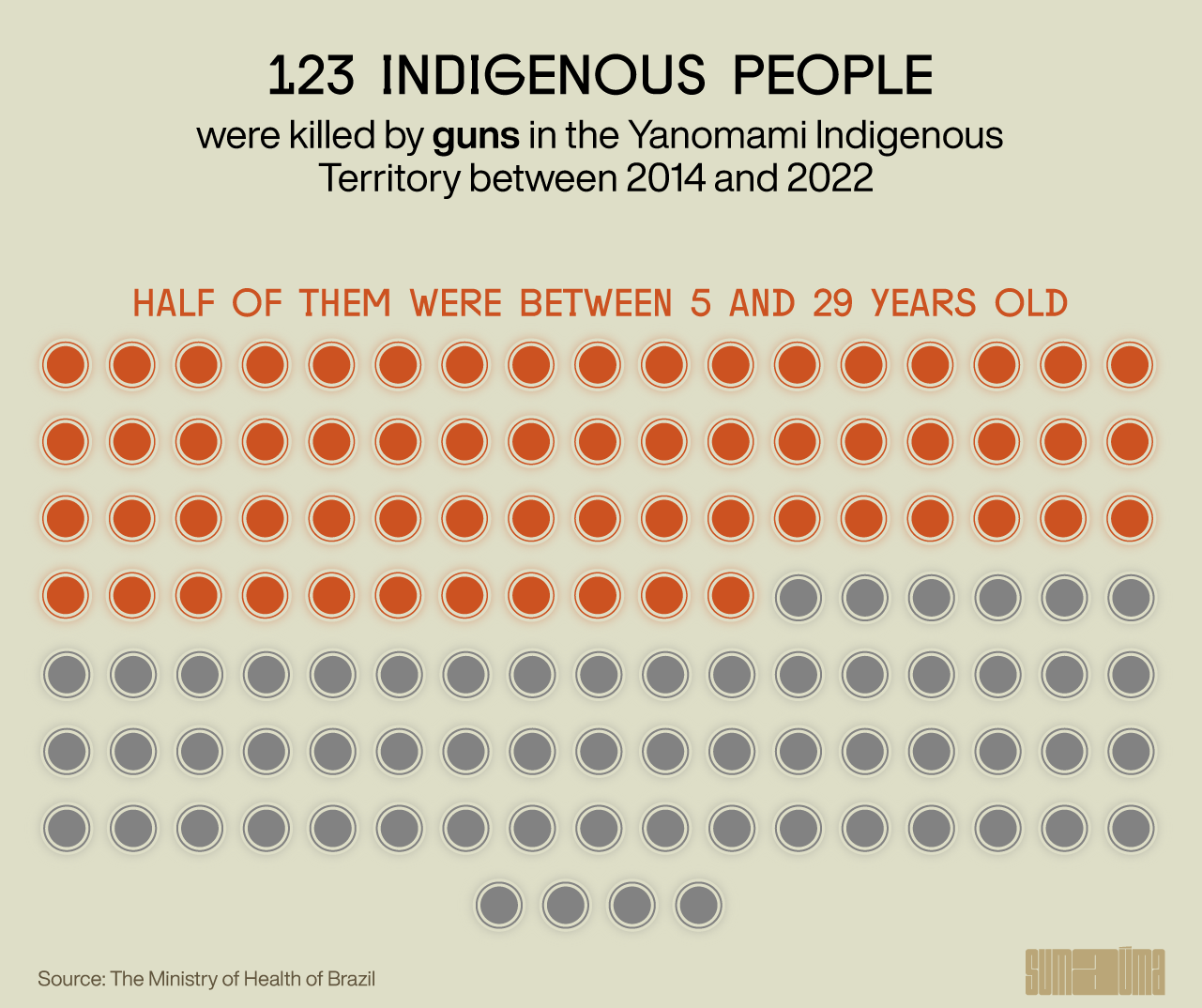

“The situation is absurd. We always had seasonal epidemics, such as pneumonia and viral infections. But without assistance, children are dying of preventible diseases, from basic causes”, explains healthcare professional who acts in the area and asks not to be identified. “The miners give drinks and guns to the Yanomami. They drink and kill one another. There are a lot of armed miners going here and there. The healthcare teams get scared and leave. How can someone work in a place like this without any safety?”

Since July 2020, the invasion of around twenty thousand miners has forced indigenous health centers to close 13 times, according to data obtained by the Information Access Act. At this moment, five are closed, one of them for 11 months. A sixth one, that was closed for four months, was only re-opened with support of the National Force. Without doctors, communities who live in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, in distant regions over an hour from the state capital Boa Vista, are denied regular healthcare.

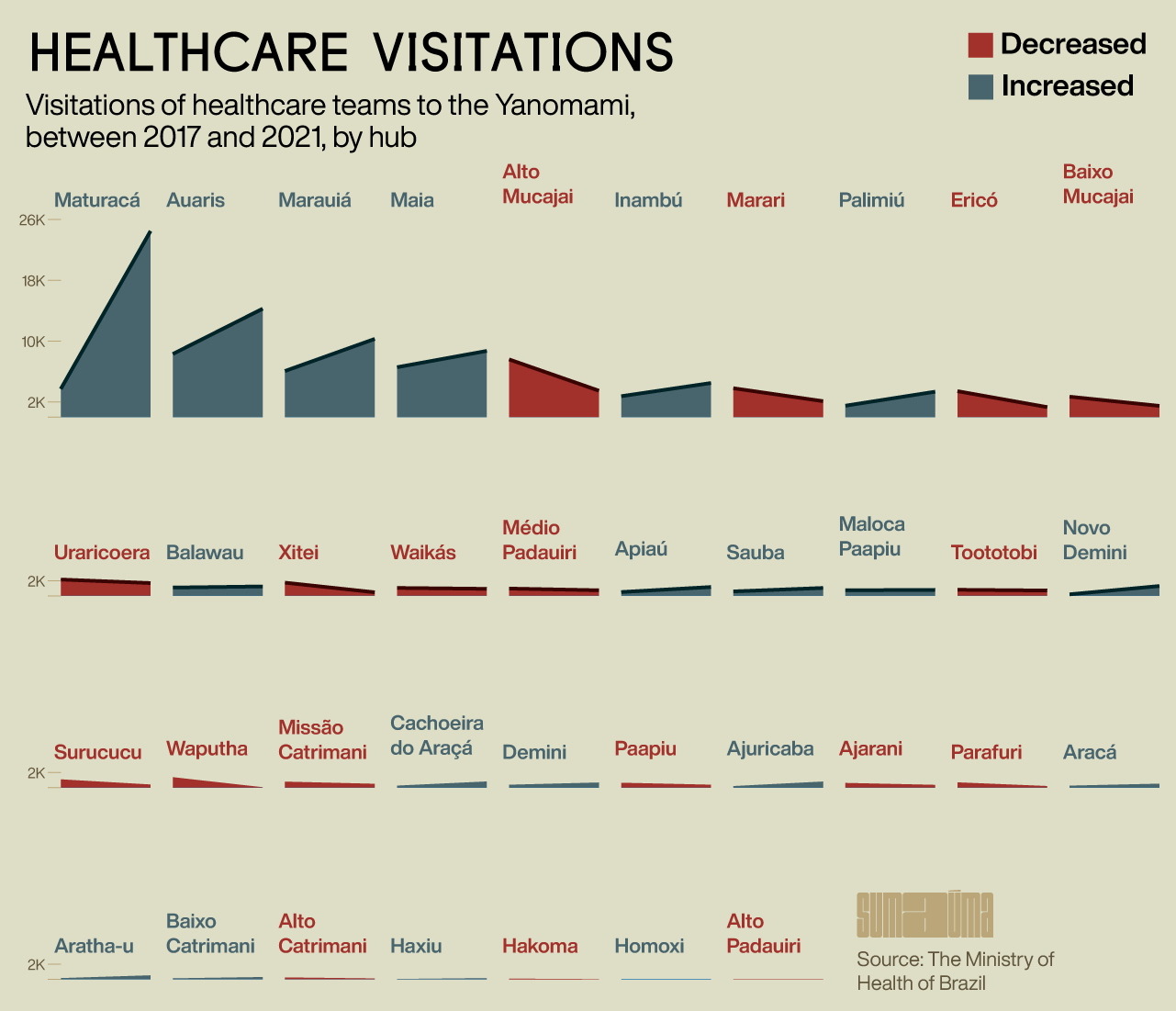

Even in the centers that remain open, mining activity has caused a negative impact. In 18 out of 37 units, visits by healthcare teams decreased between 2017 and 2021, according to public data. Worst affected are children whose health is already debilitated by malnourishment. Figures show 52.7% of Yanomami children below five years old show signs of a nutritional deficit, which is defined by a weight that is below or far below the weight expected by that age.

In the Xitei region, where 2,049 indigenous people live and where deforestation associated with mining rose 1,100% between December 2020 and the same month 2021, two children died in July with signs of Loeffler syndrome. This happens when cells responsible for acting against worms that multiply in the body attack the lungs, hampering breathing and leading to weakness. These two children would not have died if they had access to vermifuge tablets, but this treatment is lacking in the indigenous land. The Xitei center has been closed since April, when the healthcare team left after a conflict between indigenous people who were for and against mining. Five Yanomami in the region were murdered this year by guns that their leaders say were brought to the area by miners.

When the indigenous people become gravely ill in places where there are no medical teams, they need to use the miners’ internet hubs to make mobile phone contact the Special Secretary of Indigenous Health and ask for an emergency evacuation to the city. In the last year, emergency evacuations from Xitei were carried out 47 times, compared to just 26 in 2017. On many occasions, however, no one in the community has a mobile phone to ask for help.

After being taken to Boa Vista, the indigenous people who leave the hospital and continue under treatment are taken to a CASAI (Casa de Saúde Indígena or Indigenous Health House), a run-down building that is becoming a disease vector. “Feeble, feeble, feeble”. This is how one mother of Xitei region describes the condition of her son, still a baby, who she brings on her breast. The baby had pneumonia in a village lacking doctors and was taken to the city. In the CASAI, he caught a virus that provoked serious diarrhea, leading to a new hospitalization.

Hutukara believes the situation in the territory is even more serious than the public data shows. “It is very likely that many more deaths are not being notified, due to the discontinuation of the consultations”, the organization affirms in a document to the government obtained by Sumaúma. “Death certificates, once filled in by healthcare agents, are left without notification [in the system] because there is no signature of a physician”, says the document which appeals to the Brazilian authorities to solve the humanitarian crisis. The healthcare professional mentioned above confirms that deaths are likely to be underreported: “Doctors do not want to sign certificates of deaths they did not see, as they were not there.”

At the time of publication, the Ministry of Health had yet to respond to questions sent by Sumaúma on 29 August about the sanitary collapse in Yanomami Territory and asking what they planned to do to re-open health centers closed down by criminal activity.

TEXTO: Talita Bedinelli

TRANSLATION: Thiago Leal