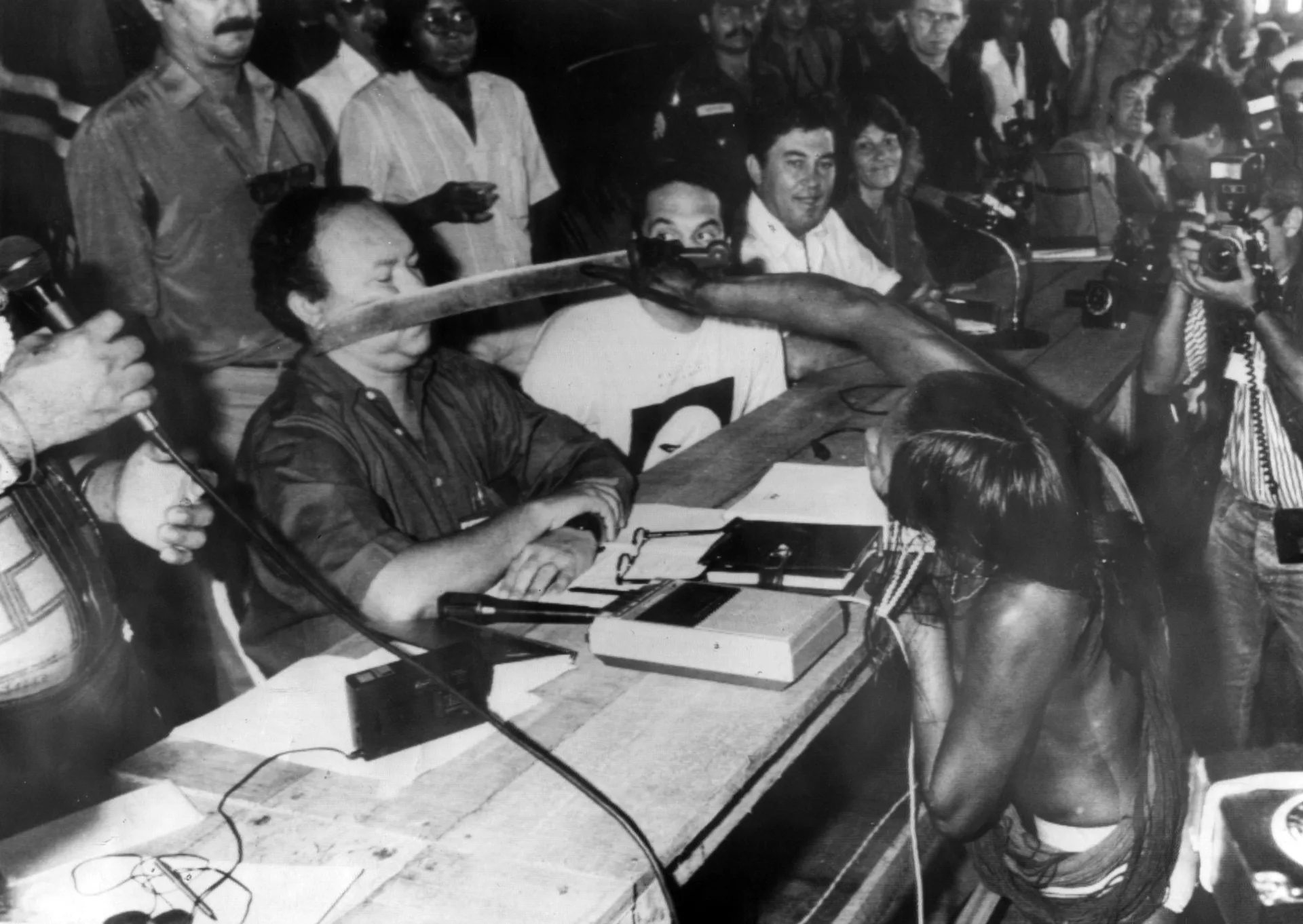

A gesture-image immortalised the defiance of an Indigenous woman in the fight for life. Tuire Kayapó Mẽbêngôkre was born a warrior. But it was when she was 19 years old, defending the forest and her land during the 1st Meeting of Xingu Indigenous Nations, in Altamira, Pará, that her cry echoed around the world. It was 1989 and Brazil was on the path to democratization after nearly two decades under a dictatorship. The scene that would symbolize the forest-peoples’ fight against Nature’s destruction was captured by many lenses and splashed across the pages of Brazil’s biggest newspapers and magazines.

Tuire’s strength to stand up to the white men and halt destructive projects like Belo Monte became a symbol of Indigenous resistance. Photo: Protásio Nene/Agência Estado

Protásio Nene, a photographer for O Estado de S. Paulo, snapped the moment when Tuire raised her machete to the face of engineer José Antonio Muniz Lopes. An Eletronorte representative, he had been appointed to the position by the José Sarney administration, tasked with circumventing Indigenous resistance to building the hydroelectric behemoth on the Xingu River, at the time called the Kararaô project. Paulo Jares, a photographer who spent most of his career covering land conflicts in the Amazon and the Indigenous struggle, also captured Tuire’s machete in the air. He was working for the Província do Pará newspaper. These two photographs, by Protásio and Jares, were circulated nationwide. Tuire died last August 10, at 54 years of age, from cervical cancer.

This Kayapó woman’s gesture halted the dam’s construction for at least two decades. The project was resurrected during Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s (Workers’ Party) first two terms in office (2003-2010), and in 2010 the Norte Energia consortium was the winner in a controversial bid. Thus began construction of one of the most disastrous human interventions since the end of the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985). The monstrosity damming the Xingu near Altamira was given the name Belo Monte and it continues to have devastating impacts to this day.

Symbol of a misguided vision of development, the hydroelectric plant brought together governments that were almost entirely irreconcilable. The first phase of operations kicked off under Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party), in May 2016. Years later, in November 2019, far-right Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party) arrived in Pará for a new landmark: this time the start of the “plant’s total power generation capacity.”

When she raised her machete in 1989, the Kayapó woman let it be known that no “white man” would take her forest, her land, and her rivers. Tuire was a critic of the Belo Monte Dam’s construction until she died – and she never quit defending her people.

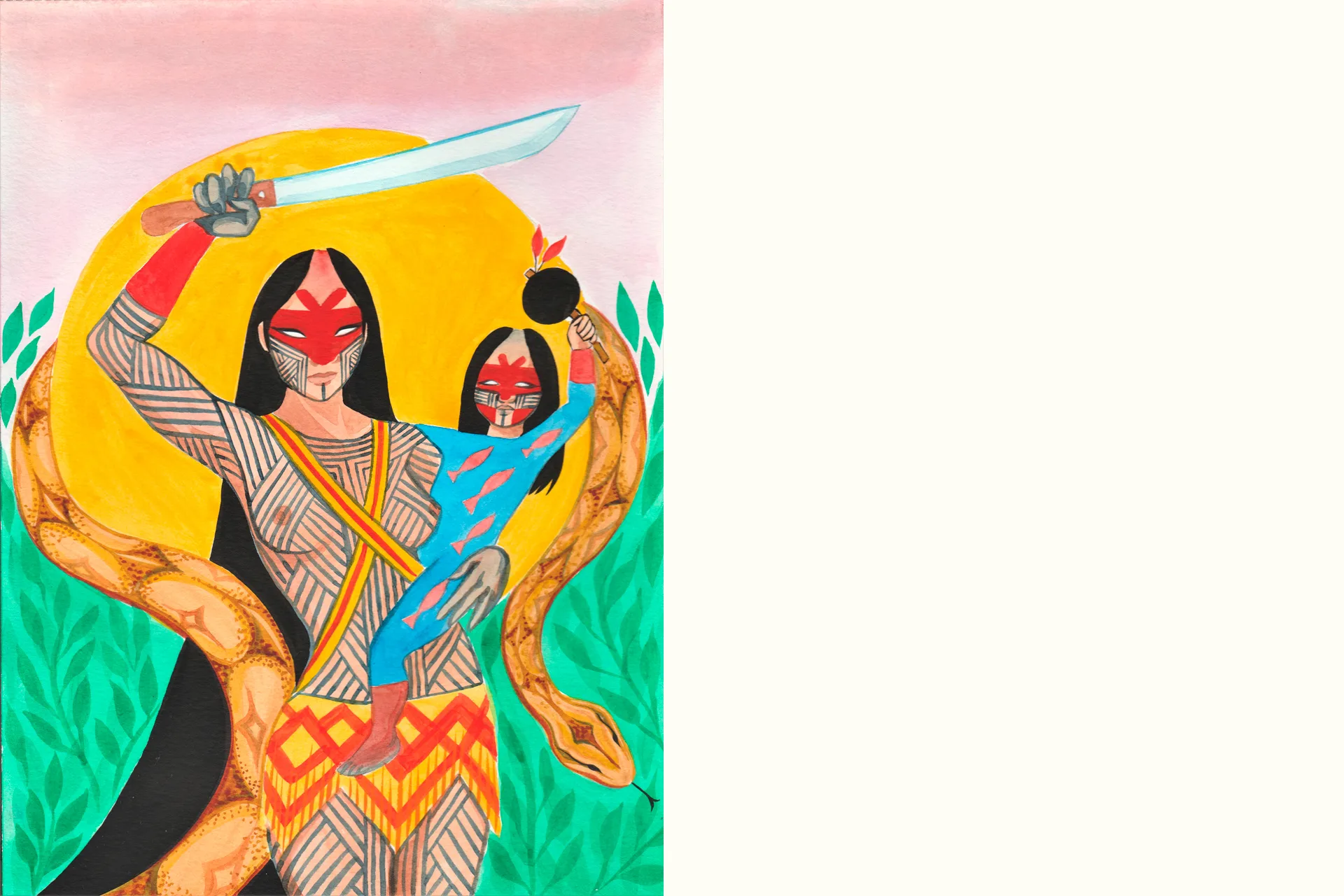

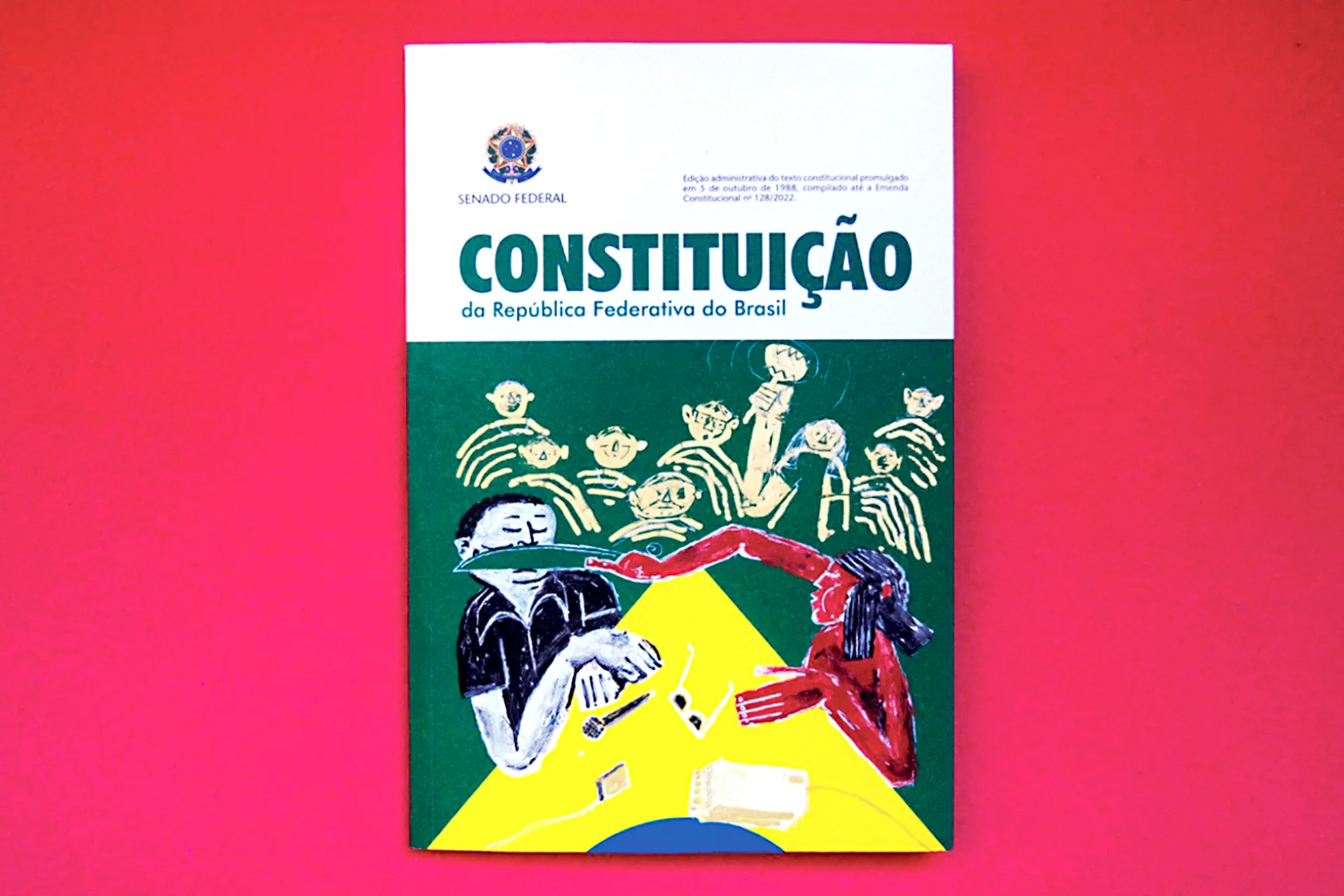

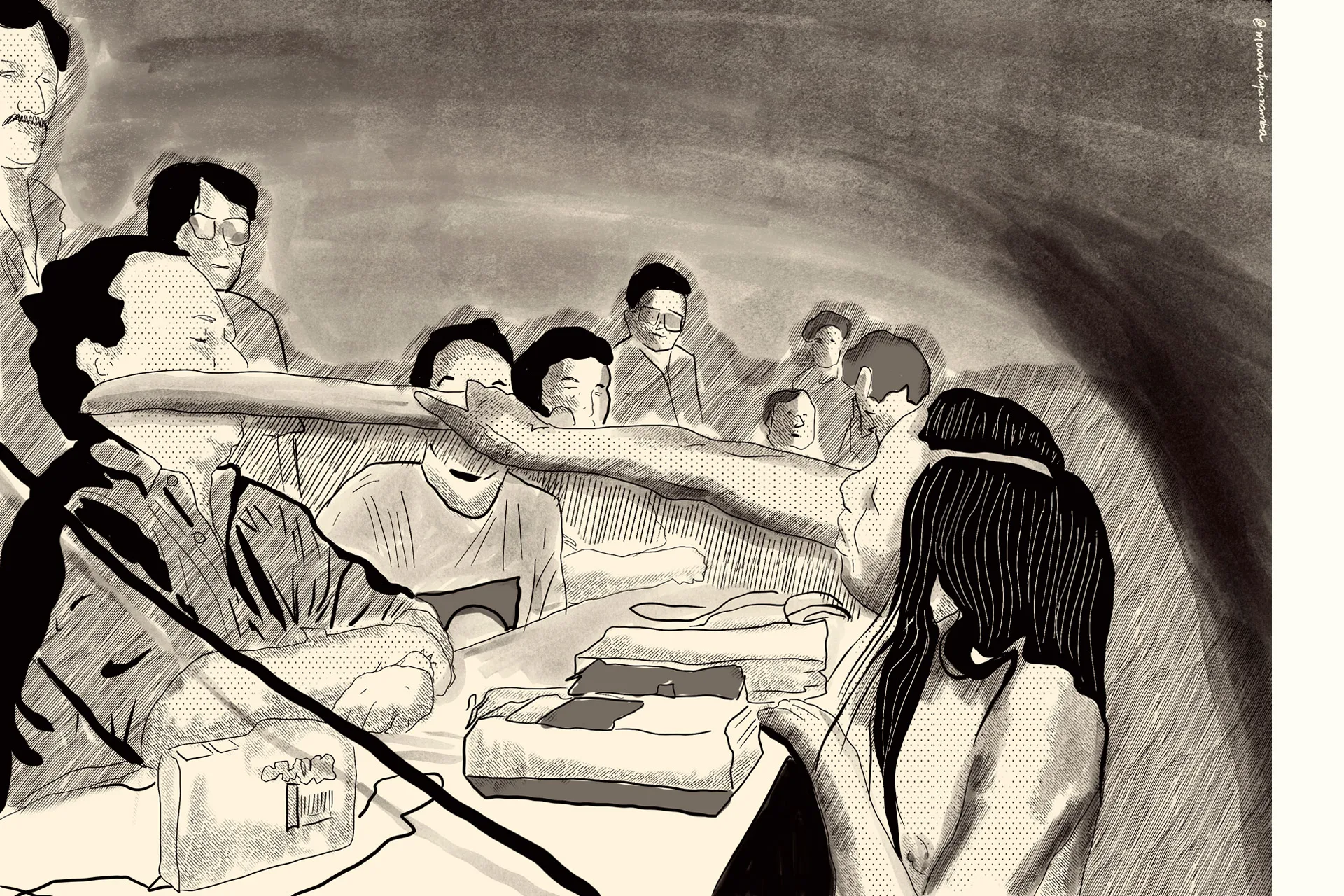

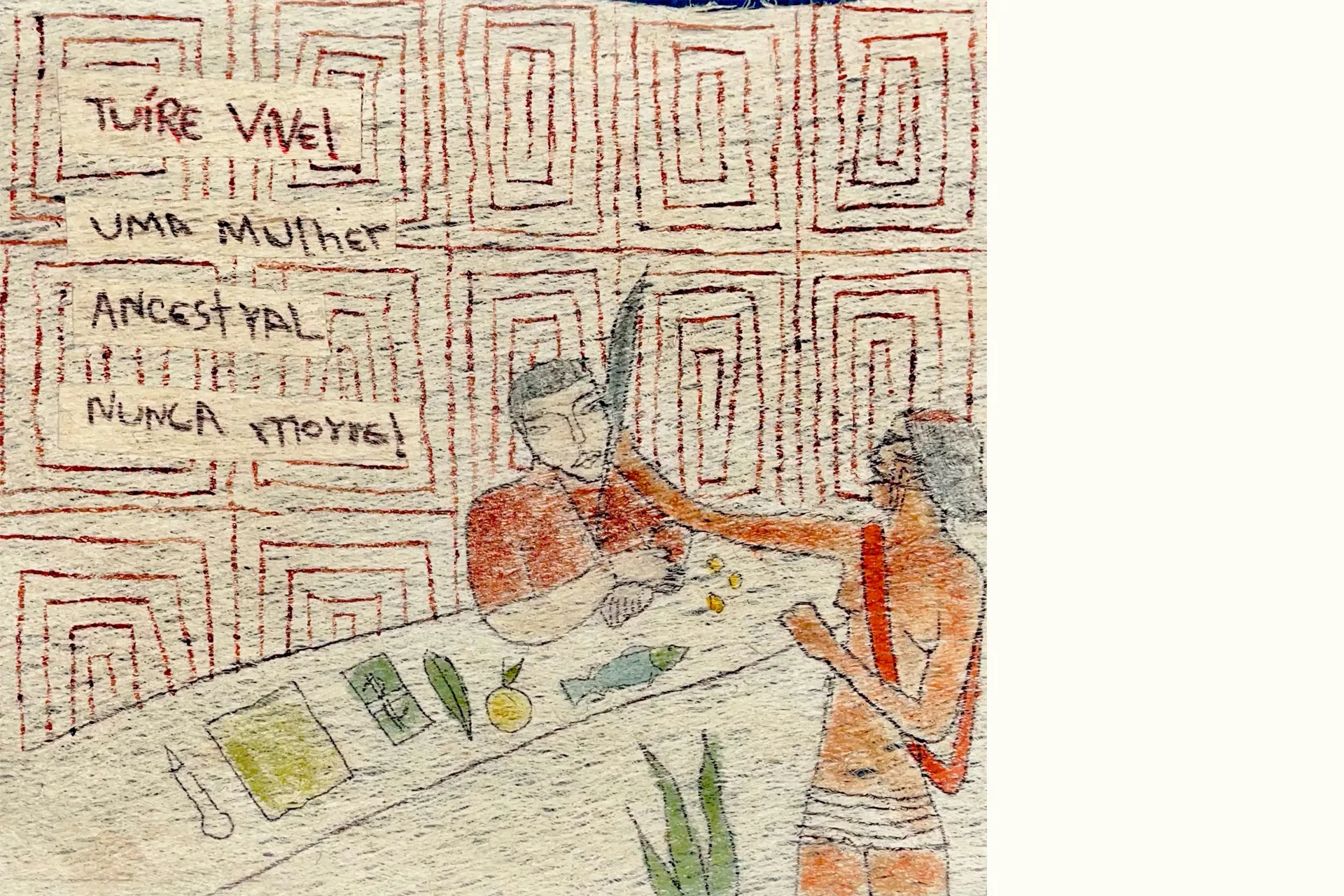

To pay homage to the Seed-woman, SUMAÚMA challenged Indigenous and Amazonian artists to reinterpret this scene that represents the struggle of the original peoples in the war against Nature waged by governments, businesses, and corporations. Tuire’s memory-gesture lives in each of them.

“Tuire is one of the Indigenous representatives who should be imprinted on the Constitution’s cover, reminding every citizen in Brazil that Indigenous rights are still being fought for and plenty still needs to be done to bring justice and dignity to Indigenous populations. This iconic image from 1989 shows the proportion of the struggles of the Indigenous movement. Our constitution is a mere 35 years old and, before this, Indigenous people were considered incompetent. Tuire is a symbol that goes beyond resistance: she represents Indigenous women’s strength and the fight for the land’s health.”

The Kayapó warrior raised the same machete, years later, to remember that her children, grandchildren and relatives embody the continued fight. Photo: Dida Sampaio /AE

Text: Malu Delgado

Editing: Eliane Brum and Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum