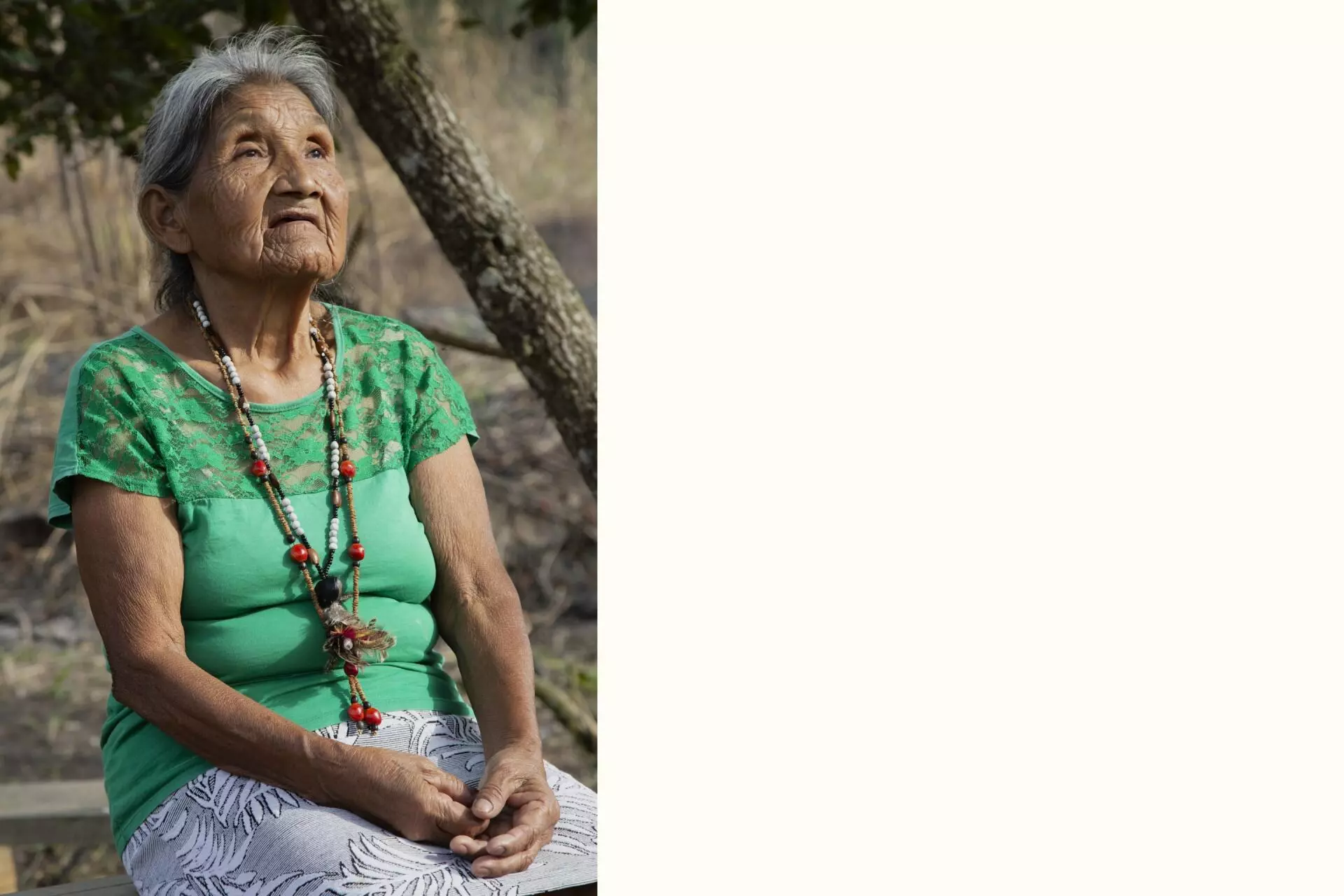

Isabel Cutschó, who is 77, is one of the elderly Xokleng and her face bears the scars of her people’s struggle. There you can see the marks left by the blade of a machete used by hired killers – the so-called “bugreiros” – who earned money from the state for chopping off the ears of Indigenous people and shooting others. She lives in the village of Sede, 20 kilometers from the center of the municipality of José Boiteux, in Alto Vale do Itajaí, in the state of Santa Catarina, in the southern part of Brazil. Sitting on a wooden bench, Isabel shows off the handicrafts she makes in the form of earrings, hair clips, necklaces, and colored bracelets. As she is doing this, the elderly woman says she has lost count of the number of times she has left the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory in order to take part in long meetings and noisy protests in Brasília or Florianópolis, which is the capital of the state of Santa Catarina. In 2021, she danced barefoot in one of the halls of the Federal Supreme Court in Brasília as a sign of protest. “It’s not that we want land, we want our land back,” says Isabel, who is married to a former cacique of the Patté clan with whom she has had seven daughters and numerous grandchildren. She will be with part of her family when she goes back to the federal capital, 1,700 kilometers away, to follow what Indigenous people regard as the ‘judgment of the century’.

Like her relatives, Isabel is anxiously awaiting June 7, when the Federal Supreme Court will resume its judgment on a case that will define the future of the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory. This judgment will establish whether or not the so-called “historic cut-off point” – a proposition that limits the rights of the original peoples by limiting demarcation claims to those who occupied their ancestral lands on the date of the enactment of the Federal Constitution, October 5, 1988. The establishment of a cut-off point for the recognition of the ancestral rights of the original peoples ignores the fact that many were expelled from their lands by land-grabbers or government projects, or were forced to flee from death threats.

Isabel Cutschó, who is 77, will follow the trial at the Federal Supreme Court, in Brasília. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

The history of the struggles of the Xokleng people spans generations. Apart from Isabel’s scars, it is also reflected in 5-year-old Sofhya Koziklã Teiê Priprá hugging a Brazilian sassafras (Ocotea odorifera) tree, which sprouted in the back of the Vanhecu Patté Kindergarten and Elementary School, in the village of Bugio. This species used to be abundant in the region, but because it had been used to such a great extent by the construction industry, in the early 1990s it entered the official list of Endangered Species of Brazilian Flora. Apart from its “hardwood”, the Brazilian sassafras exhibited another property that attracted lumber companies: its immense capacity to produce the essential oil safrole, which is used in the production of medicinal products and cosmetics. The tree gives its name to the Sassafras State Biological Reserve, created in 1977, with an area of 5,229 hectares, divided into two properties, in the municipalities of Benedito Novo and Doutor Pedrinho.

The struggle for this territory has been going on since the 1990s. The Xokleng have always maintained the land was theirs, but at that time their leaders were not clear on how to act. The movement got a boost from an anthropological report from the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai), in 1999, confirming the expansion of the area of the biological reserve. The case that is currently under discussion at the Federal Supreme Court began in 2009, with an action for repossession filed by the then Environment Foundation, which is now the Environment Institute of Santa Catarina. The area claimed by the Xokleng overlaps the reserve and has been identified as part of the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Land. The demarcation line of the territory began to be drawn, but the state of Santa Catarina filed a claim for repossession. Since 2013, the process has been at a standstill .

In 2019, things seemed to be moving toward an understanding based on a public conciliation hearing, at the Federal Supreme Court, mediated by Minister Edson Fachin. However, there was no agreement. At present the vote is tied, with the rapporteur Fachin voting against the requests of the government of Santa Catarina, whilst the Minister Kássio Nunes Marques, who was chosen by the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro when he was president, voting in the state’s favor.

Sofhya’s hugging of the tree that takes years to grow and can reach a height of 25 meters carries a hope that extends beyond the Xokleng’s territorial limits. This is because, in 2019, the Federal Supreme Court gave the case general repercussion status. What this means is that a judgment in this case will serve as a guideline for all the courts with regard to the demarcation of Indigenous lands in Brazil.

Sofhya Kozikla Pripra, who is 5, hugs a Brazilian sassafras tree, the species that gave its name to the reserve created in 1977. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

The Laklãnõ/Xokleng live in the northwest part of the state of Santa Catarina, in the Alto Vale do Itajaí region. To get to the Indigenous Land, which stretches across the four municipalities of José Boiteux, Doutor Pedrinho, Vitor Meireles, and Itaiópolis, you have to travel on dirt roads. The route is confusing: one minute you are on Indigenous land, and the next minute on non-Indigenous land with plantations of corn, tobacco and fruit trees. There are a lot of trucks transporting pine logs.

Roughly 486 farming families are in the conflict area, but they did not invade it. Most purchased the land legally from the State, with deeds attested in notary offices, under government projects that ignored the Indigenous people’s rights, which were only fully recognized in the 1988 Constitution. However, 150 of these families have no way of proving the legitimacy of their claim because they acted in bad faith by invading what they knew was Indigenous territory. As a result of this they should not be entitled to any compensation.

The Xokleng, who call themselves the ‘people of the sun’, number about 2,300 in nine villages, all of which have political autonomy. Leaders are chosen by direct vote at regular intervals. In one of the country’s coldest regions, the houses are built of bricks. To travel the dirt roads, most families have cars. Apart from the Xokleng, who represent the overwhelming majority, the territory is also home to families of Guarani and Kaingang, two other original peoples who live in the state of Santa Catarina with an estimated statewide population of 17,000.

For centuries they were nomads and lived as hunter-gatherers, occupying the forests that covered the mountain slopes, the coastal valleys and the edges of the plateau in the South of Brazil. During this long-gone past, they suffered competition from other Indigenous groups for control of the fields and pine forests. Later on, living on the slopes of the plateau and in the coastal valleys, they saw those lands gradually taken over by non-Indigenous people. Once “Independence” had been proclaimed Brazil began to favor the immigration of Europeans. During this process, the Indigenous people suffered the consequences of political and economic decisions that were implemented with extreme violence.

“The saga of the Xokleng is often confused with the history of immigration in the South of the country, particularly in the state of Santa Catarina, where there was a significant influx of immigrants of German origin. In the Alto Vale do Itajaí region, colonization was only affirmed to the extent that the Indigenous people were confined to the reservation,” wrote Sílvio Coelho dos Santos (1938-2008), who had a PhD in anthropology and was a professor at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, in his book The Xokleng Indians – Visual Memory (Os Índios Xokleng – Memória Visual).

Márcia Vaicomem Vei-Tchá Teiê with her daughter Sofhya Kozikla Pripra, in front of the replica of the underground homes formerly used by the Xokleng people to withstand the cold in the village of Bugio, in the municipality of José Boiteux. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

Who defends Indigenous children?

The tension leading up to the judgment on the ‘historic cut-off point’ in the Federal Supreme Court even affects the school community. Concern escalated after a video circulated in which political leaders and farmers from the region talked of “bloodshed” and “civil war” if the so-called “black cloaks” (the name given to the Ministers of the Federal Supreme Court), only look out for the interests of the Indigenous people. Narrated by the federal deputy Rafael Pezenti (Brazilian Democratic Movement party for the state of Rio Grande do Sul), the video stresses the importance of “private property” and the deeds issued to those who bought land, saying that it is “very bad when people’s history is thrown in the trash.” At no time whatsoever does the deputy mention what has been done with the ancestral past of the Xokleng people and their relationship with the land, which precedes the European immigrants’ relationship with it by several millennia. He ends by stating that if the Federal Supreme Court commits this injustice (against the historic cut-off point), there will be “bloodshed”.

In order not to spread panic, the leaders asked the Indigenous people not to share the content of the video. Nevertheless, many people watched it. The teachers are afraid of reprisals and are considering bringing forward their vacation, which is scheduled to start on July 15, to July 5.

Especially worrying is the situation of the kindergarten students, who need to go outside the Indigenous land. Every day, starting at 6 am, the bus with the students travels along the road that goes through the area of farmers involved in the conflict. Following the invasion and murder of four children in a daycare center in the city of Blumenau, on April 5, security was reinforced in the state’s public-school network. This is the case at the Laklãnõ Indigenous School of Basic Education, in the village of Pliplatõl, where security guards take turns and cones were placed at the main entrance. No one enters without being identified.

Even so, Indigenous teachers are afraid. “Our fight is not with the farmers, who are also victims of the State that sold them land that was not theirs to sell, but we know that in situations like this the children are always more vulnerable,” says the vice-cacique Jussara Reis dos Santos, who is 37 and the daughter of a Xokleng mother and a descendant of a European immigrant.

Women are particularly concerned. Some of them ask not to be identified. “In the countryside, everyone has a gun at home. We have always faced prejudice on account of our way of life, but the relationship with our neighbors was normal,” says a Xokleng woman. “The historic cut-off point has made things worse, and we, the mothers, are afraid because a lot of weapons have been registered by hunters. This talk reflects the women’s fear of the consequences of the Bolsonaro government’s encouragement of gun ownership throughout Brazil.

Handicraft classes at the village of Bugio’s Indigenous School, in the municipality of Dr. Pedrinho. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

At least 150 Xokleng are expected to go to Brasília for the vote. One bus will leave the city of Florianópolis with Indigenous students from the Federal University of Santa Catarina. There is a very strong desire in the villages to take part in this historic moment. So much so that each of the nine chiefs had to indicate who would be part of the group. According to Tucum Gakran, the main cacique (communal leader) who lives in the village of Coqueiro, the uncertainty about what will happen on June 7 has been taken into account. “You can’t leave the community unprotected, and that could happen if the voting carries on for a few days. We have sent a letter to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples with a request for federal police to be deployed,” he explains. The cacique said it was unlikely that school vacations would be brought forward, as that would require a formal request to the State Department of Education. “The government of the state of Santa Catarina is not on our side. Apart from the lawsuit that gave rise to the historic cut-off point, the current governor, Jorginho Mello (Liberal Party), has been bringing a lot pressure to bear in Brasília against the Xokleng cause. We have teachers with tenure and we are afraid that they will also suffer persecution,” Tucum says.

Community, gathered at the Laklanó Indigenous School, discussed the effects of the judgment of the historic cut-off point and determined which leaders would travel to Brasília. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

Risk of repeating the past

The attorney Rafael Modesto dos Santos is working in defense of the Xokleng people. The central argument he proposes is that the historic cut-off point is unconstitutional. According to Santos, the state of Santa Catarina is making a mistake by defending only one side of history. “The state of Santa Catarina defends the rights of the ruralists, when in fact it shouldn’t be defending anyone’s rights. It has chosen a side, in the same way that in the last century it paid hired killers, called ‘bugreiros’ to hunt down, drive off and kill the Indigenous people,” he says.

According to the attorney, the hired killers’ actions are a stain on Brazilian history that the state needs to recognize. Both the Brazilian State as a whole along with the state of Santa Catarina, which in the past was responsible for paying those who hunted the Indigenous people. In this case, he argues that the very least that should be done to repair this historical violence would be to return the entire territory to the Xokleng.

The defense lawyer speaks of monetary reparations – an inalienable right that does not expire no matter how much time passes – which can be discussed in court and requested from the federal government’s Amnesty Commission. “At the moment, we are hoping the territory’s return is done as a reparation mechanism, but of course this does not interfere with a possible discussion regarding the right to reparations on account of the violence committed by our institutions, in particular with the state of Santa Catarina, against the people who were hunted down and murdered.”

The lawyer’s assessment is that the approval of the historic cut-off point would result in “an enormous cultural loss to the country”. In addition, the Indigenous groups that are living on roadsides, on the edges of highways, in improvised camps or at the back of farms, because their lands have been invaded, would be expelled and as a natural consequence would be forced to fight for space on the outskirts of the cities.

Asked if he was of the opinion that this could cause a phenomenon similar to what occurred when the so-called Lei Áurea (Golden Law – which abolished slavery) was signed, on May 13, 1888, the lawyer is emphatic: “Just as the ‘end of slavery’ pushed poor populations without the conditions to survive to the outskirts of the cities, a vote in favor of the historic cut-off point will condemn the Indigenous people to a very similar situation.”

This opinion is not shared by the lawyer Márcio Vicari, who is the attorney general of the state of Santa Catarina. Until he took office on January 2, he had been following the historic cut-off point case from a distance. On May 15, Vicari took part in a public hearing in the state of Santa Catarina’s Legislative Assembly. “The state government is dedicated to defending Santa Catarina’s farmers,” he assured. The meeting was proposed by the Assembly’s president, Deputy Mauro de Nadal (Brazilian Democratic Movement party). Five deputies and nine representatives of entities, linked to agricultural or business federations, took part in the meeting. All of them declared themselves to be in favor of maintaining the historic cut-off point.

The attorney general refutes the argument that the state is biased. “The defense of the Indigenous people is handled by the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples (Funai), and by the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The state that I represent today is defending its own interests, as well as those of the Institute of the Environment (IMA), which is an autonomous state entity, and has maintained this position since the start of the process,” he claims. “It is not a position in favor of A or B, but to defend an area of environmental protection, the Sassafras Reserve.”

Extermination as a political strategy

The history of the original peoples in Brazil is defined by blood. The Xokleng are among those who have suffered the greatest number of atrocities. In 1956, the Indigenous Protection Service demarcated their territory. But with only 14,000 hectares – rather than the 37,000 hectares that had been recognized by the government of the state of Santa Catarina itself, back in 1914. The aim was obvious: while the Xokleng were restricted to that smaller area, the rest of the land was “sold off” to companies and settlers, who began to register it. Thus, we have a conflict situation which was generated by the public authorities themselves.

Almost 100 years later, the Xokleng people are still waiting for the ratification of the remaining 23,000 hectares. In the 1970s, under the military dictatorship that oppressed Brazil from 1964 to 1985, the federal government decided to build the North Dam, which is now the municipality of José Boiteux. The dam, which was a construction project designed to contain the rivers’ waters, took up 15% of the 14,000 hectares that had been guaranteed to the ethnic group, further reducing the Xokleng’s land. The largest structure of its type in the country, it was built to prevent flooding in the municipalities of the Vale do Itajaí.

The construction evicted people from their homes, totally ignoring the Xokleng’s existence and caused flooding to a large part of the Indigenous territory. There were a number of negative impacts for the Xokleng, including on crop cultivation, family coexistence, and education. By preventing the flow of the waters of the Hercílio River, the dam punished the community with successive floods. The family leaders then decided to look for other places to live, moving far away from their relatives. As a result, many Indigenous people migrated to urban areas, becoming paupers on the outskirts of the cities of the state of Santa Catarina.

Memories of horror

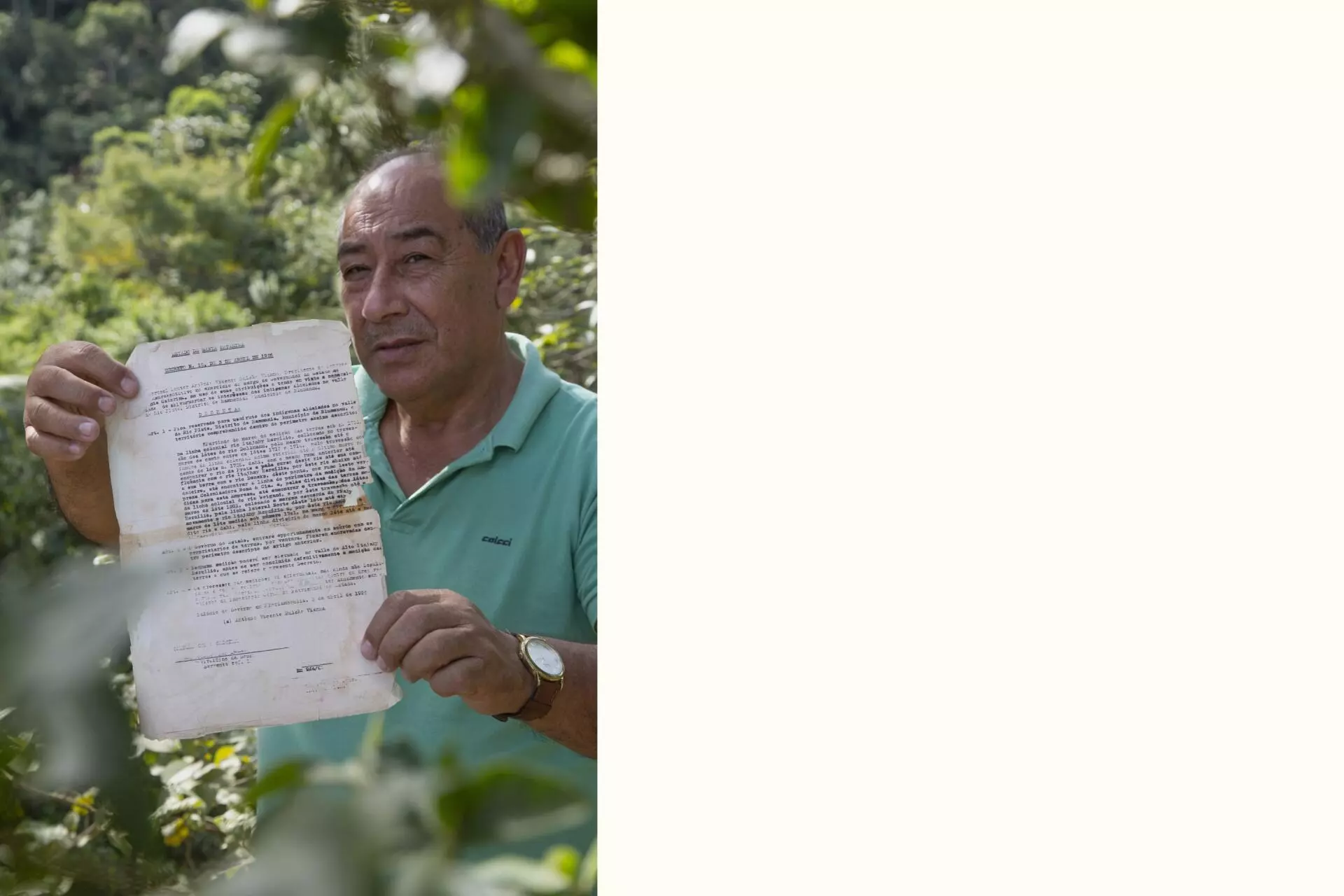

Brazílio Priprá, 65, lives in the upper part of the village of Palmeira. Without ever having been elected chief, the former Funai employee is one of the most knowledgeable people regarding the Xokleng reality. For at least 36 years he has accompanied the back-and-forth of his people’s ceaseless efforts in search of the definitive recognition of their ancestral territory. In the house surrounded by fruit trees and araucaria trees, which is a species that is typical of cold regions and that produces pine nut seeds, he keeps a document that he regards as sacred: a decree from the then governor of Santa Catarina State, Bulcão Vianna, dated April 3, 1926, including the area that is currently in question within Xokleng territory: “The farmers who bought the land knew, the logging companies knew, and the State knew: these lands belong to the Xokleng. The state, which sold the area to the companies and the companies to the farmers, should pay compensation to the families,” he states.

Even though he did not personally experience the atrocities of the past, he gets emotional when he talks about what he heard from his elders. One of the saddest episodes occurred in August 1904: children were thrown up into the air and stabbed with daggers. On that date, 244 Indigenous people were killed by the state. The episode was described in the now extinct “Novidades” (News) newspaper from Blumenau: “The enemies spared nobody’s life. After having started their work with bullets, they finished it off with knives. Nor were they moved by the groans and cries of the children clinging to the prostrated bodies of their mothers. Everybody was butchered.”

Priprá grew up listening to stories like this, “I cry at these atrocities. I am the grandson of people who helped bring the community out of the bush, to make contact (with non-Indigenous people). It’s been more than 100 years, but for our people it’s just like yesterday.”

Brasílio Pripra shows a document signed by the then-governor of the state of Santa Catarina, back in 1926, recognizing the 37,000 hectares of Indigenous land. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

These memories of so much violence still haunt the villages today. “The historic cut-off point case has made the people anxious. Our people carry a trauma with them from long ago, when our ancestors were almost exterminated,” explains Priprá.

This memory, observes the math teacher Abraão Kovi Patté, who has an Intercultural Indigenous teaching qualification from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), is reexperienced whenever he is in the municipality of Ibirama, 30 kilometers from José Boiteux and en-route to the Indigenous reserve. “On the roundabout on the main avenue, the monument commemorating the town’s one hundredth anniversary shows us how much prejudice is culturally ingrained in the region,” he points out. The educator refers to the small square made of stones with bronze sculptures in honor of the city’s founding groups. “The immigrants, represented in the figures of the farmer, the pioneer, and the worker, stand upright, and look imposing, while the image of the Indigenous person is smaller, in an inferior position compared to the others.”

Notwithstanding this, the Indigenous people’s presence in the “European Valley,” as they call it in the state of Santa Catarina, is strong. When it was founded, the village was called Hamônia colony, but had its name changed to Dalbérgia. In 1943, it was renamed Ibirama, which in the Indigenous language means “Land of Plenty”.

“I want to stay here until the land swallows me up”

“I have nothing left,” says Rosinei Pedroso, an Indigenous cook who lives on the side of the road that borders the former headquarters of the Sassafras State Biological Reserve. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

Rosinei Pedroso, or Rose as she is known is 47 years old and is the cook in a camp along the road that borders the former headquarters of the Sassafras State Biological Reserve. The Kaingang Indigenous woman is married to the Xokleng Ndili Kopakã, who together with other men works cutting pine trees. They have been living with their daughters and grandchildren in canvas tents for almost seven years. The proximity to land that is in dispute has a high price: sometimes their pots, dishes and clothes have been thrown to the ground. At least once this was done by police officers. “I’m not afraid of anything else. I don’t think I’m doing anything wrong except fighting. I want to stay here until the earth swallows me up,” says Rose, as she warms herself around the wood stove sipping a yerba-mate.

For 10 years, Natan Cuzon Crendo, 33, was a machine operator in one of the largest manufacturers of household linen products in the Itajaí Valley’s textile hub. Like most of the young people, he left in search of a job. But he came back to the village of Bugio, where he lives with his wife, who is pregnant with their second child. He says he was moved by a feeling that is common among others who have left and returned. “I can’t let the legacy of my ancestors die: I was with my mother when she was camped at the North Dam, a construction site that did nothing but harm to our people, and where she got sick and died. My son is one year old and every time I pick him up in my arms, the suffering of our people comes flooding back to me.“

Bugio, unlike the other villages of the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory, is 1,000 meters above sea level. Natan uses this geographical factor as a comparison to the challenges faced by a Xokleng: “Only God can push me down.”

In the same way that Natan wants his son to know the history of his ancestors, the Xokleng youth have already decided to stand up and be counted. In addition to a strong presence on social media, the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Land’s young people have taken the lead in the struggle. With dances, songs, painted bodies, round-table discussions and protests, they have taken the cry of the Xokleng to various different places. They have already been to the Federal Supreme Court, the Esplanade of the Ministries, the streets of the city of Florianópolis, and the Legislative Assembly of Santa Catarina.

Natan Cuzun Crendo and a relative from the village prepare for an assembly to discuss the judgment of the historic cut-off point. FOTO: DANIEL CONZI/SUMAÚMA

“All the elders have waited for the demarcation of the whole of our territory. We want to honor our grandparents, our ancestors and all those who passed away without being able to see this historic moment become reality,” says Kagdan Crendo, who is 16 and a communicator in the youth group. Ten days before the vote at the Federal Supreme Court, the high school student from the village of Plipatõl admits that he is so anxious regarding the decision that he is having trouble sleeping. “The historic cut-off point has brought our people together. Elders and young people, Catholics and Evangelicals. We have our differences, but right now nothing is more important than the issue of the land.”

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Mark Murray

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Érica Saboya