On July 18, SUMAÚMA reported that an Indigenous woman of the Kokama people had been raped routinely by at least four military policemen and a civil guard for more than nine months. With her baby by her side. The raping continued to be inflicted on her in the jail at the Santo Antônio de Içá police station in Amazonas state until the child was ten months old. Think about this: instead of learning to walk and talk, this baby watched his mother being raped, watched his mother bleed, watched his mother scream, watched his mother being humiliated and destroyed. And all of this took place at facilities belonging to the government, which had a responsibility to protect this woman and this child, and it was also done at the hands of state agents, who had a responsibility to protect this woman and this child.

The exclusive report by Rubens Valente forced authorities at various levels of power to stop pretending that what happened hadn’t happened. But until SUMAÚMA published the story, all of these institutions remained silent, for at least two years. And they would have maintained their silence, perhaps forever, if the crimes hadn’t been brought to light, with national and international repercussions. It was only after publication of the report that three policemen and a civil guard were arrested, the State raised its initial offer of roughly 6,200 dollars in damages to around 54,000 dollars, and K was switched to semi-open confinement.

To understand how two years of silence was possible, connections must be made. If they aren’t made—despite the broad disclosure of these crimes, from sexual violence to omission on the part of the authorities—what is now determining our extinction will stay hidden. And please note: “extinction” isn’t a metaphor here; it’s a fact.

It is important that part of Brazil and the world be shocked and moved by a crime like this. It is crucial that K—as SUMAÚMA calls this Indigenous woman to protect her identity—receive justice and all the assistance she needs to recover as much as possible from the lasting physical and psychological damage inflicted on her, along with her child. It is essential that the series of violent acts suffered by K—which began with serial rape and persisted with the silence and complicity of the authorities and institutions involved—serve as a watershed, prompting new public policies to be crafted and existing laws to be enforced. Because if laws had been enforced, K would not have been raped.

But all this is far from enough.

The annual report “Violence Against Indigenous People in Brazil,” published on July 28 by the Indigenist Missionary Council, shows that cruelty against this population increased in 2024 while victim age fell. Of the 20 episodes of sexual violence documented in the report, 14 were committed against children and adolescents aged 4 to 16. Additionally, 211 Indigenous people were murdered in 2024, and 922 children aged 0 to 4 died, many from preventable causes such as malnutrition and infectious disease.

The Makira-E´ta Network of Indigenous Women of Amazonas State has called attention to data that signal a brutal upsurge in violence against Indigenous people in Brazil. In ten years, from 2014 to 2023, violence against Indigenous women soared 258%, exceeding the 207% increase in the national average of violence against women as a whole. Worse yet was the growing sexual violence; while overall figures rose 188%, the rate was 297% among Indigenous women. These numbers come from a survey by the Brazilian website Gender and Numbers, based on reports of violence against Indigenous women compiled by the health ministry’s database, DataSUS.

K is not alone when it comes to the horrific violence perpetrated against incarcerated females, who are often celled with men in Brazil. The intellectual Carla Akotirene, cited by philosopher Djamila Ribeiro in her column for Folha de S.Paulo, made the trenchant observation that a prison is a microstructure of a society of captives. Carla said technologies of oppression—patriarchy, racism, ethnocide, capitalism—intersect and materialize inside prisons. A jail cell is thus colonialism reincarnated. “A cell becomes a domestic environment,” Carla said, “where men enter and rape, and when women try to scream for help, they’re punished for indiscipline.” According to Carla and Djamila, this constitutes systemic institutional failure, where omission, complicity, and the naturalization of violence join forces against racialized bodies.

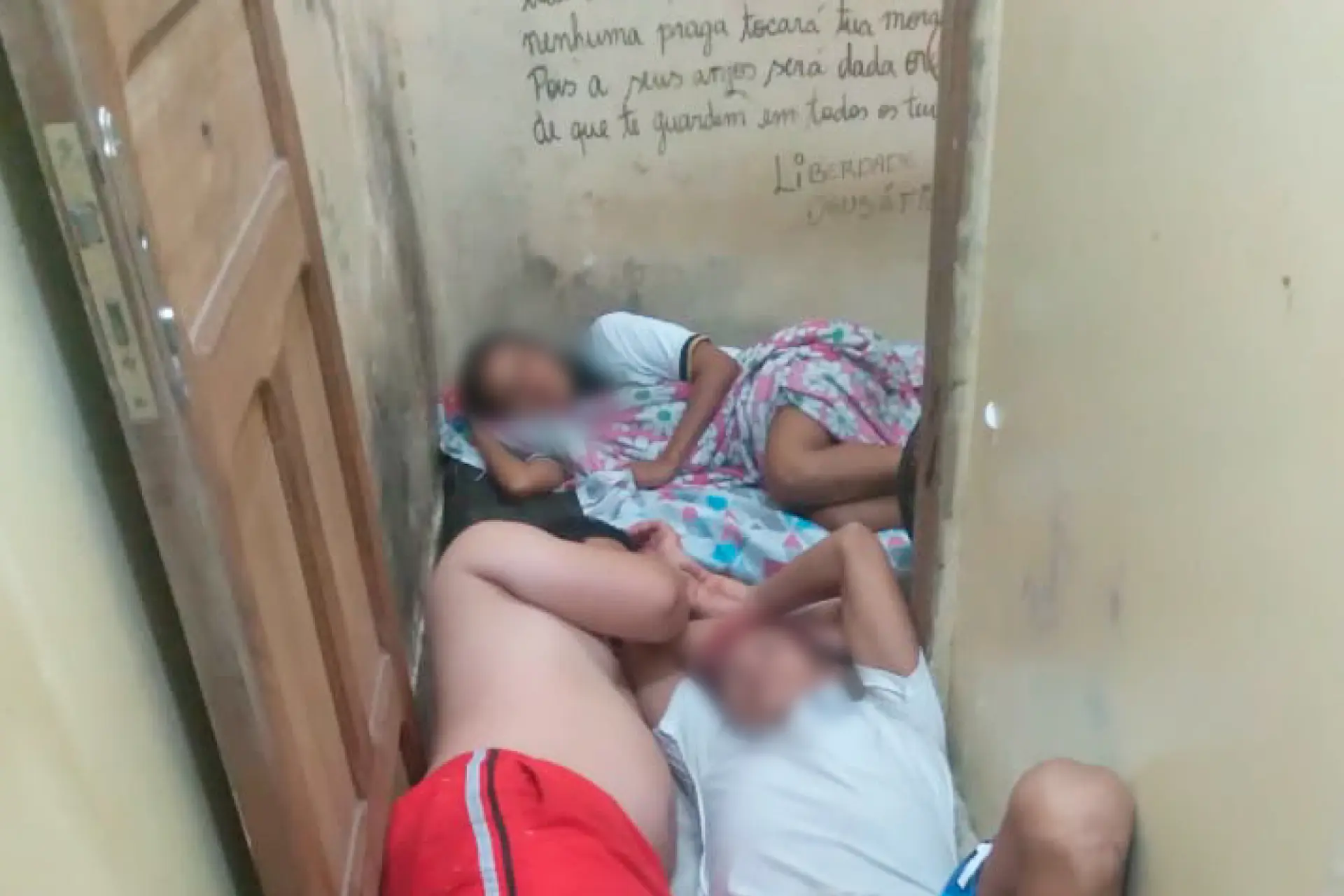

Santo Antonio do Içá, Amazonas: an Indigenous Kokama woman was imprisoned together with men and raped by agents of the State. Image courtesy of attorney Dacimar Carneiro

SUMAÚMA was envisioned to do journalism from and about the Amazon and its peoples, covering the collapse of the climate and biodiversity, an issue that necessarily intersects with the markers of race, gender, class, and species. In our co-training program for forest-journalists, we strive to practice journalism that accompanies the movement of Nature, where everything is connected and interdependent, not compartmentalized and pigeon-holed into boxes and news departments, following the logic of those who—as thinker Ailton Krenak puts it—have separated themselves from Nature.

All efforts to halt the growing number of rapes of Indigenous women will not be enough if Indigenous lands are not demarcated. I have been writing and repeating for many years now that it isn’t possible to understand the advance of deforestation—clearing land for the monoculture of soy and livestock—without understanding the role of the patriarchy. The same logic that violates the body of the Amazon Forest, other tropical Rainforests, the oceans, and all the biomes is the same logic that violates women’s bodies. The Forest’s body and women’s bodies have been converted into objects-bodies to be invaded, dominated, violated, and depleted.

Those who combat violence against women must combat violence against Nature. It is not a matter of one debate here and another there, one struggle here, another there—they’re all one and the same.

This is why Brazil’s Congress has taken aim at the demarcation of Indigenous territories. It is territories-bodies that are at stake. Without demarcation, biomes-bodies will be subjugated just like what happened when the European invaders arrived in 1500 and what continued in subsequent centuries, with the incursion into Indigenous lands and the conversion of Nature into commodities. With demarcation, violation becomes harder. Demarcated bodies will be less subject to rape in Brazilian jails as well. What is demarcated is not subjugated.

For those of you currently looking in puzzlement or derision at the screen where this text is displayed, consider the memorable words of Jair Bolsonaro, the former president who is now on trial for his alleged involvement in a coup attempt following the 2022 elections. In 2019, during his first year in office, Bolsonaro said, referring to the Forest and to Europe’s supposed greed for the Amazon: “Brazil is a virgin every foreign pervert wants.” The brutality of the far right is enlightening.

Only intersectionality with race, gender, and class allows for a deep understanding of the Brazilian Congress’s recent attacks on Marina Silva, minister of the environment and climate change. Originally from the traditional Amazon people known as Ribeirinhos, having learned to read and write when she was 16, this Black woman occupies the most challenging political post in Brazil today, embodying resistance to the escalating devastation of the planet’s largest tropical rainforest and all other biomes, both inside and outside the Lula da Silva administration. It is her body more than any other that stands between the chainsaw and the Forest.

When Marina was verbally ambushed in the Senate, on May 27, where she had been called before the infrastructure committee, members of both the opposition and the administration left her to bleed. The scene, which went viral, exposes the intimate relationship between the patriarchy and the violation of Nature that has led to the collapse of the climate and biodiversity.

Let us remember this.

“She deserves respect as a woman but not as a minister,” declared Senator Plínio Valério—the same senator who some time ago said he would like to hang her. Committee chair Marcos Rogério, an ally of Jair Bolsonaro, cut Marina’s microphone whenever she tried to defend herself from the attacks. Eventually the chair roared, “Know your place!”

They hate the minister because Marina has hindered—less than she would like and much more than Lula wants—the advance of efforts to exploit the Amazon and all other biomes. They hate Marina for what she is trying to prevent from happening, and they express this hatred because she is a woman. They hate the idea and violate the woman.

Marina Silva embodies resistance: her very body stands between the chainsaw and the Forest. Photos: Andre Violatti/Ato Press/Folhapress and Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

The violence endured by Marina Silva because she has resisted from a position of power—where her body (infected with Leishmaniasis and contaminated by mercury) is the one that blocks the offensive on the Forest-body—is key to understanding this moment. In the Amazon and all other biomes, leadership of the fight to defend Nature lies with women, just as young women are also the leaders of the climate and humanitarian movement started by Greta Thunberg, another woman harassed even by self-proclaimed progressives because she denounced the connection between the genocide produced by Israel and the fight against the climate collapse. When Greta pointed out that you can’t call yourself an ecologist unless you combat the ecocide being committed by Israel, she was butchered on social media and in opinion articles and videos. Women are always at the forefront of the fight against extinction, and this is no accident.

The collapse of the climate and biodiversity, which will condemn vast segments of the population to death if it isn’t halted, has a gender. It was caused by men, and today it is still mostly men who make the decisions now accelerating the catastrophe, as left blatantly clear by the Brazilian Congress. It also has a color, since both the colonialism and capitalism that produced it were white men’s projects. It is no coincidence that resistance to this force of destruction also has a gender, and that in recent decades non-white women have come to play a growing leadership role in global struggles.

This relationship is rendered invisible in scientific reports, by a science that is likewise white, largely dominated by men, and yet defines the course of events. At this very moment, oppression is destroying our planet-home. And confronting misogyny and sexual violence, just like confronting racism, means saying no to projects that destroy Nature.

Let us also remember the racist attack by Deputy Kim Kataguiri (Brazil Union) against the Indigenous Deputy Célia Xakriabá (Socialism and Liberty Party) during the vote on the Devastation Bill, the greatest assault on Nature and on our present since Brazil’s military-business dictatorship (1964-1985). “The peacock is an animal from over in Asia; it has nothing to do with Indigenous tribes [sic] here in Brazil. But some people seem to like cosplay,” said Kataguiri, clearly addressing one of the few Indigenous deputies in the history of Brazil. Célia, with the words “legislated ecocide” and “futuricide” written across her chest, was wearing a headdress of peacock feathers. “Cosplay” is the practice of wearing the costume of a fictional character. “This was a sacred headdress worn by the Fulni-ô people,” Célia replied. “I have no problem knowing where I come from. And [calling this cosplay] is televised racism,” added the first Indigenous woman elected federal deputy for the state of Minas Gerais.

Indigenous Deputy Célia Xakriabá, wearing a headdress, in Congress: “This is televised racism.” Photos: Luciano Candisani/SUMAÚMA and Bruno Spada/Chamber of Deputies

Accusing Indigenous people of faking their identity is a common ploy. A few years ago, it was fashionable in Brazil to call them “Paraguayan Indians,” a twofold racist attack—against the Indigenous and against Paraguayans. Sometimes they’re accused of pretending, other times they are told they weren’t on their lands in 1988, the year Brazil enacted its latest Constitution, and therefore have no right to the territory, as argued in the law that established the historic cut-off point—an unconstitutional law that deliberately ignores the fact that, if an Indigenous people wasn’t occupying their territory right then, it was either because they had been driven off it or they had to flee to avoid extermination. It is worth remembering that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bolsonaro government only registered people as Indigenous if they lived in officially recognized territories. The thousands who were in un-demarcated territories or in cities were counted with the general population—and thus deprived of their identity and their rights as Indigenous people. The strategy is clear: don’t demarcate territories, do destroy biomes, and anyone who lives in a city and claims to be Indigenous is faking it. This goes against the Constitution, but they’ve already taken a chainsaw to the charter.

Minutes before he attacked Célia Xacriabá, Kim Kataguiri had this absurdity to say: “Well, I’d also like them to build a hydroelectric dam next to my house; I’d also like a highway next to my house.” He was suggesting that Indigenous people were opposed to the Devastation Bill out of an alleged economic interest, because under it they would lose their right to compensation for the irreversible damages major construction projects have wrought on Indigenous territories. “It’s about money, about dough, it’s a scam,” he said, mocking all victims and all destruction produced by big hydropower plants and highways, especially in the Amazon.

It should be borne in mind that Kataguiri is a founder of the Free Brazil Movement, the digital militia that since 2013 has embraced the worst characters in Brazilian politics, from Eduardo Cunha to Jair Bolsonaro, and whose lies have resulted in death threats against some people. This is the same mold that shaped Arthur do Val, who said about the women of Ukraine, attacked by Russia’s despotic Vladimir Putin: “They’re easy because they’re poor.”

It was against this revolting backdrop that the Devastation Bill—which dismantles the system for protecting Nature-body and permits the rape of territories-bodies—was approved by a Congress whose majority represents the interests of big corporations operating in soybeans, meat, mining, ultra-processed foods, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and weapons.

The town of Sinop, Mato Grosso, doesn’t even look like the Amazon: part of the Forest-body has been destroyed by soy monoculture. Photo: Diego Baravelli/SUMAÚMA

It should also be noted that patriarchal relations are entrenched, even in the progressive camp. The law recently passed by Congress was dubbed the Devastation Bill to convey the true scale of what it represents. It has another nickname, likewise popular—“the mother of all stampedes”—an allusion to the words of Ricardo Salles, environment minister under Bolsonaro, who, during a meeting between the then president and all ministries, said that since the press was busy covering the pandemic that was killing thousands a day, it was a good time to “open the gates and let the cattle through”—in other words, proceed apace with the dismantling of the legal framework meant to protect Nature. That’s basically what Congress has just done.

But why the “mother” of all stampedes? There is no mother in this story written mostly by men. A much more appropriate criticism would be the “father” of all stampedes. The distinction might seem trivial, but a cliché is a cliché because it represents something. The devil is truly in the details.

Movements in the Amazon are now connecting struggles, and women know fighting violence against their bodies is fighting violence against the Forest-body. In the Middle Xingu, Antonia Melo, one of the main voices speaking out against Belo Monte and the violence inflicted on women, is an example of a leader who has always connected battles. Antonia Melo knows it’s not one struggle here and another there, but one same fight.

For most urban movements, this isn’t the case. Torn from Nature, organizations and activists seem to have a harder time re-establishing connections in the city. Even for the urban environmental movement, gender issues rarely enter the debate. Separating out the so-called environment and assigning it to its own niche is a terrible political strategy that allows the traditional press as well as politicians of various stripes to say “environmentalists are against” this or that, as if the questions didn’t concern the population as a whole and as if the set of players weren’t much broader. Disconnection and compartmentalization are the logic of capitalism. In Nature (and not in “the environment”), all bodies are connected and interdependent.

At the global level, movements such as Me Too and their offshoots, which broke the silence surrounding rape culture, must go a step further and expand their understanding and actions: the fight will only be complete if a connection is made between women’s bodies and biomes-bodies, now undergoing accelerated destruction that could culminate in the extinction of life. Confronting gender violence means confronting the destruction of Nature-bodies. Unless this is understood, women like K will continue to be violated, because their territories were violated before they were. To end the rape of women, we must also end the rape of Nature. And unless the rape of Nature is stopped, we will continue toward extinction at an accelerating pace.

Protesting the Devastation Bill: it is impossible to understand the advance of deforestation without understanding the role of the patriarchy. Photo: Lela Beltrão/SUMAÚMA

Text: Eliane Brum

Collaborator: Rafael Moro Martins

Art Editor: Cacao Sousa

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Castilian translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum