Salgueiro’s samba song at this year’s Carnival parade includes a number of terms from Yanomami cosmology that tell us how this Indigenous people conceive of the world, the land they inhabit and their relationship with the forest, and other beings of nature and napëpë, or non-Indigenous people. SUMAÚMA has put together a glossary to help our readers better understand the show to be presented by Salgueiro in Rio de Janeiro’s Sambadrome arena. The glossary draws from the books The Falling Sky (Belknap Press) and The Spirit of the Forest (Companhia das Letras), both co-authored by the Yanomami shaman, thinker, and leader Davi Kopenawa and the French anthropologist Bruce Albert. The two men began their collaboration almost 50 years ago, and their books are grounded in deep friendship, a political commitment to the life of the Yanomami, and Bruce’s honest, rigorous dedication to rendering Davi’s thoughts faithfully when he translates the shaman’s words to other languages-worlds.

Yanomami

The Yanomami people inhabit lands in Brazil and Venezuela and today form one of the largest Indigenous groups in Brazil, with a population of some 31,000 in the states of Amazonas and Roraima. They sustain themselves by hunting, fishing, gathering, and planting and, in some villages, by purchasing food from the city. Ratified as a territory in 1992, their lands extend across 37,000 square miles, [DG1] making theirs the largest Indigenous territory in the country.

The word “Yanomami” derives from a simplification of Yanomamɨ tëpë, which means “human beings.” Some groups living in the western part of the territory apply the term to themselves. “Yanomami” has now come to define the entire ethnic group, while within the six languages making up the Yanomami linguistic family the word for “human being” corresponds to the name of each ethnic group: Yanomam, Yanomamɨ, Sanöma, Ninam, Ỹaroamë, and Ỹanoma.

According to their cosmology, the Yanomami people were created by Omama after their long-ago ancestors, the yaroripë, lost their original form as both humans and animals. Their vital images—or utupë, a constituent part of all beings—entered the cast of entities that are visible only to shamans: the xapiripë. Their skin, however, was transformed into forest animals, or yaropë, who continue to display human characteristics, such as subjectivity and sociability.

Omama and Yoasi

Omama is the creator of the Yanomami, who are the children of Omama and his wife, Thuëyoma, “a fish being that let itself be captured in the appearance of a woman,” as Davi says in The Falling Sky. “Omama had a lot of wisdom. He knew how to create the forest, the mountains, and the rivers, the sky and the sun, the night, the moon and the stars. It was he who made us exist and established our customs in the beginning of time. He was also very beautiful,” says Davi. Omama will be featured near the front of Salgueiro’s parade, represented by a 65-foot-high statue.

In the beginning, there was only Omama and his brother, Yoasi, who “came into existence alone,” without a father or mother. Because Yoasi was jealous, he became Omama’s antagonist. He put malevolent entities on earth to wreak destruction. The origin of death, disease, and all evils is attributed to Yoasi. Omama, on the other hand, wanted people to be immortal, like the sun-being, Mothokari. Davi has often credited Yoasi for the emergence of the napëpë, or non-Indigenous. According to the lyrics of Salgueiro’s samba song, Yoasi thinks he is “righteous,” a veiled allusion to the far-right Bolsonaro movement, which worships guns and despises the forest and its peoples.

Hutukara

The title of Salgueiro’s samba theme song is the word used by Yanomami shamans to refer to the first sky, which fell in ancient times to form today’s earth. The first sky tumbled down after the ancestral yarori pë had committed a series of transgressions. Given the destruction and pollution of the planet by non-Indigenous people today, the Yanomami fear the sky will fall again. Omama, creator of the Yanomami, shaped a “more solid” earth. He planted “huge pieces of metal” from the old sky deep inside the new earth to keep it from collapsing as well—and the napëpë should not dig these out.

Hutukara is also the name of one of the ten Yanomami associations. Founded in 2004 and now led by Davi Kopenawa, the Hutukara Yanomami Association fights for the rights of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana peoples, both inhabitants of Yanomami Indigenous Territory. The association’s logo depicts the present-day world, with its forests, mountains, land, and rivers. On each side of this image are two adornments of macaw feathers, symbolizing the shamans, who are responsible both for protecting the land-forest, or urihi a, and for holding up today’s sky so it won’t fall again.

Hutukara logo. Headed by Davi Kopenawa, this is one of the ten Indigenous associations in Yanomami territory

Urihi a

Urihi a designates the forest and its ground, or the land-forest. It can also refer to a person’s specific birthplace or current home. The land-forest is a living being, so it shouldn’t be treated as a commodity. “What you call ‘nature’ in our language is urihi a, the land-forest, and also its image seen by the shamans, Urihinari a. It is because this image exists that the trees are alive. What we call Urihinari a is the spirit of the forest,” Davi says in the book The Spirit of the Forest.

The shaman explains that the forest has në ropë—the power of fertility—which is its wealth. There is also a “vital breath,” or wixia, which lends plants the power to grow and gives them their vitality. The land-forest feels pain when its trees are cut down or burned to be replaced by dry, arid, hot land.

In a narrower sense, urihi a signifies the concentric spaces connected by the trails that extend from the Yanomami’s collective houses to the places where they hunt, gather, and farm, sometimes closer, sometimes farther from their homes. As defined by Bruce Albert, the Yanomami territory is “transportable,” because the model has been reproduced over the course of this people’s migrations. Invasions by illegal miners and loggers threaten the lives of the Yanomami because these criminal activities restrict, contaminate, and destroy the spaces where they hunt, gather, and plant—spaces where life moves in interwoven ways.

Xapiripë

Omama created the xapiripë at the request of his wife, Thuëyoma, who was worried about how to heal children. The xapiripë are summoned to cure disease and regulate the rhythms of nature, dictating the seasons of rain or drought and ensuring the world is in balance. Shamanic healing confronts evil entities, “who see humans as their prey […] and therefore take possession of their vital images to devour them,” as Bruce Albert writes in The Spirit of the Forest. In the words of Davi Kopenawa, “The xapiripë are the masters of nature, of the wind and rain. When the children and nieces of the wind spirits play in the forest, the breeze flows, and it is cool. […] If the xapiripë are far away in the sky, and the shamans don’t summon them, the forest gets hot. Epidemics and evil spirits come closer. Then humans keep falling ill.”

In the samba arena, the xapiripë will be represented by the group of grand marshals that traditionally opens every school’s parade and will also appear on Salgueiro’s floats. According to the shaman, the xapiripë “are as tiny as light dust,” miniature people exhibiting bright, colorful adornments. “They dance atop huge mirrors. Their songs are magnificent and powerful. Their thought is straight, and they work hard to protect us.”

There are countless xapiripë, and they never die. They correspond to the original vital images of the Yanomami’s ancestors, the yarori pë, and the ancestors of all beings. Every being has a xapiri, from great trees like the kapok (or sumaúma), to animals, stones, leaves, waters, the moon, the sun, and thunder. Even the non-Indigenous napëpë have their xapiripë. “The xapiripë have defended the forest for as long as it has existed. They were always at the side of our ancestors, who for this reason never destroyed it,” says Kopenawa. Shamans, who both have and see xapiripë, are called xapiri thëpë.

Yãkoana

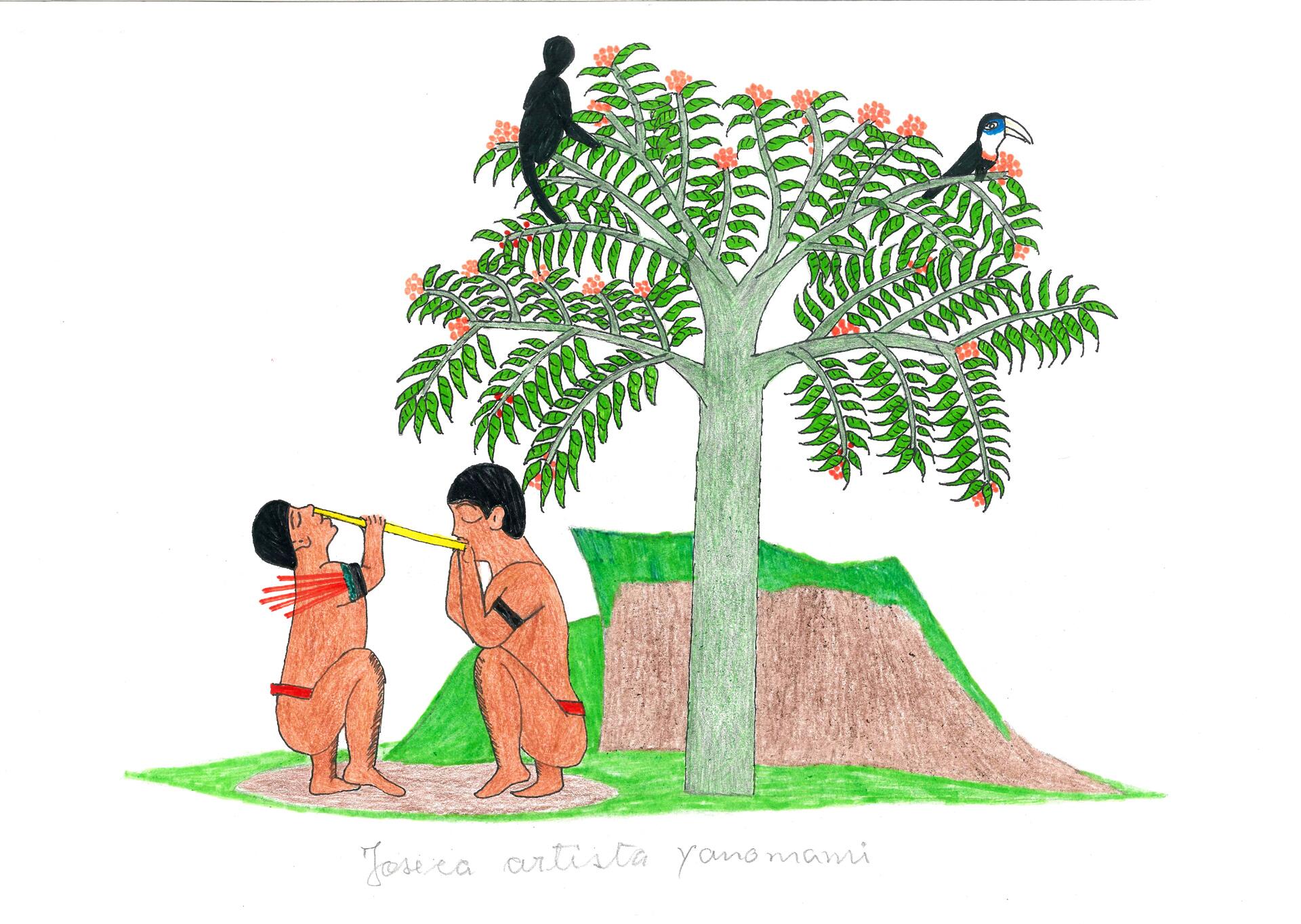

Yãkoana is a powder made from the resin of trees of the genus Virola. It is one of the most common hallucinogens employed by Yanomami shamans to contact and summon the xapiripë. The xapiripë are in turn nourished by yãkoana. Another man blows the powder into the shaman’s nostril through a two- to three-foot-long tube made from the hollowed stem of a palm tree or a tall cane grass known as caña flecha[DG2] .

Davi Kopenawa has promised to take some shamans to the Sambadrome, where they will perform the ritual. In The Spirit of the Forest, Davi says he is concerned that young Yanomami “worry too much about commodities and white people’s talk,” and they don’t want to be initiated as shamans. “Some are even afraid of the power of yãkoana powder, and they sometimes refuse to become shamans. They’re frightened of the spirits and fear their hostility,” he writes. If younger generations don’t see the xapiripë and listen to what they say, the words of the ancients will be lost, and the forest and its people left unprotected.

“When the yãkoana seeds are born, toucans and spider monkeys feed on them. We, Yanomami, also use them in our shamanism.” By Joseca Mokahesi (2018)

Napëpë

In the Yanomam language, napë means someone who is not Yanomami or is an enemy or foreigner. When the suffix pë is added to form the plural—napëpë—the term can be applied to enemies, whites, or foreigners. After nearly all of the Yanomami’s neighboring ethnic groups vanished in the early 20th century, following the white people’s invasion of their lands, the word napëpë came to refer mainly to the non-Indigenous. Davi Kopenawa also calls whites “commodity people.”

Xawara

Xawara means “epidemic.” The Yanomami believe disease spreads in the form of smoke, or xawara wakixi—epidemic smoke. Their first contact with non-Indigenous people came in the early decades of the 20th century, when the intruders brought in successive waves of disease. Since then, this smoke has been associated with gunpowder and metal tools, such as the machetes traded to the Yanomami.

Contact was initially made by religious missionaries and the former Indian Protection Service, and it increased under the business-military dictatorship (1964-1985). The regime began building the Perimetral Norte highway through Yanomami land but never finished the project; it also initiated mineral exploitation in the forest, an activity that then continued in the form of illegal wildcat mining. With the invasion of some 40,000 miners, the late 1980s and early 1990s saw a dramatic expansion of criminal mineral extraction. Even after the Yanomami Indigenous Territory was ratified in 1992, the invasion went on. A new surge of miners came in 2016, and the situation worsened greatly under the Bolsonaro administration (2019-2022).

As Davi Kopenawa explains, “epidemic smoke” also rises when the metal and oil that Omama hid in the “underworld”—the ancient land below Hutukara—are extracted. The Yanomami believe it was Yoasi, Omama’s jealous antagonist, who informed the non-Indigenous of these ores. “White people grew very numerous, and they started destroying the forest and dirtying the rivers. They manufactured great quantities of goods. They built cars and airplanes so they could rush faster. And to manufacture all this, they dug into the earth to rip out things that have been there since Omama hid them. That’s how they began spreading the epidemic smoke that has destroyed the earth and made its people fall ill,” writes Kopenawa in The Spirit of the Forest.

Ya temi xoa

The refrain of Salgueiro’s samba song can be translated literally “I’m still alive,” but in its broader sense, it means a person enjoys good physical, mental, and emotional health. One of Davi Kopenawa’s requests was that the creators of the school’s central theme not portray his people as victims but as resisters. The Yanomami are the people who hold up the sky and sustain life in the forest and on the planet.

Lyrics to Salgueiro’s samba theme song

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Meu Salgueiro é a flecha pelo povo da floresta

My Salgueiro is the arrow for the people of the forest.

Pois a chance que nos resta é um Brasil cocar

The only chance that’s left us is Brazil with a headdress.

É Hutukara, o chão de Omama

It’s Hutukara, ground of Omama,

O breu e a chama, deus da criação

darkness and flame, god of creation.

Xamã no transe de yãkoana

The shaman in the spell of yakoana

Evoca xapiri, a missão

will summon xapiri for their mission.

Hutukara ê, sonho e insônia

Hutukara ê, dreams and insomnia,

Grita a Amazônia antes que desabe

cries Amazonia before it falls.

Caço de tacape, danço o ritual

Hunting with my bludgeons, dancing my rites,

Tenho o sangue que semeia a nação original

it’s my blood that seeded our original nation.

Eu aprendi o português, a língua do opressor

I learned Portuguese, the language of my oppressor,

Pra te provar que meu penar também é sua dor

so you will know that my torment is also your lament.

Falar de amor enquanto a mata chora

To talk of love although the forest is weeping

É luta sem flecha, da boca pra fora

is to fight without arrows, pay lip service only.

Falar de amor enquanto a mata chora

To talk of love although the forest is weeping

É luta sem flecha, da boca pra fora

is to fight without arrows, pay lip service only.

Tirania na bateia, militando por quinhão

Tyranny of panning, armies after gold,

E teu povo na plateia vendo a própria extinção

while your people on the sidelines watch the extinction of their own.

Yoasi que se julga família de bem

“Yoasi,” you consider yourself to be “righteous”—

Ouça agora a verdade que não lhe convém

Listen to the truth, though you don’t want to hear.

Yoasi que se julga família de bem

“Yoasi,” you consider yourself to be “righteous”—

Ouça agora a verdade que não lhe convém

Listen to the truth, though you don’t want to hear.

Você diz lembrar do povo Yanomami

You say you think of Yanomamis

Em 19 de abril

on Indigenous Day,

Mas nem sabe o meu nome e sorriu da minha fome

but you don’t even know my name and you laughed at my hunger

Quando o medo me partiu

when my fear cut me in half.

Você quer me ouvir cantar em yanomami

You want to hear me sing “Yanomami”

Pra postar no seu perfil

for you to post to all your friends,

Entre aspas e negrito, o meu choro, o meu grito

putting quote marks and bold letters ‘round my sobbing and my shouting—

Nem a pau, Brasil

No way, Brazil!

Antes da sua bandeira, meu vermelho deu o tom

Before your flag came along, it was my red that set the tone.

Somos parte de quem parte, feito Bruno e Dom

We’re all part of the departed, like Bruno and Dom.

[Reference to the Indigenous specialist Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips who were murdered in Javari Valley, in the Amazon, in June 2022]

Kopenawas pela terra, nessa guerra sem um cesso

Kopenawas for their land in this war that never ends.

Não queremos sua ordem, nem o seu progresso

We don’t want your “order” or your “progress” either.

[An allusion to Brazil’s national motto]

Napê, nossa luta é sobreviver

Napë, we’re fighting to survive.

Napê, não vamos nos render

Napë, we will not give up.

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Ya temi xoa, aê-êa

Meu Salgueiro é a flecha pelo povo da floresta

My Salgueiro is the arrow for the people of the forest.

Pois a chance que nos resta é um Brasil cocar

The only chance that’s left us is Brazil with a headdress.

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Malu Delgado (news and content), Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (coordination)

Director: Eliane Brum

Omama fishes out Thuëyoma, daughter of Tëpërësiki, the being of the bottom of the waters. The first Yanomami came from the love between Thuëyoma and Omama. By Ehuana Yaira (2023)