Photos: Pablo Albarenga

THE YANOMAMI WOMAN SITS ON A WOODEN BENCH, SWATTING AWAY RELENTLESS MOSQUITOES. A necklace of long yellow beads crisscrosses her naked breasts and drapes over her pregnant belly. As her four-year-old snuggles up, she laments how skinny he is. “He’s been eaten away by malaria,” she explains. In a forest invaded by mining interests that now control the area, children like him die of disease after days or weeks of high fever and persistent vomiting. Malnutrition has been a reality for several years, and it has worsened in a number of villages. In territories under the control of illegal mining, Yanomami children vomit out worms. Medicine is slow to arrive, if it arrives at all. Then the woman starts telling us what she fears more than hunger or malaria, even more than children throwing up worms. She tells us what the miners do to the women.

Foto: Pablo Albarenga. Imagens: mulheres Yanomami

The body of the world’s largest tropical forest, a major regulator of the planet’s climate, has been violated and invaded by some twenty thousand illegal miners in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, an area of over 37,000 square miles (96,000 square kilometers) between the states of Roraima and Amazonas in northern Brazil, close to the Venezuela border. The invaders open craters in the ground, dig up riverbeds with their huge dredges, and dump vast amounts of human waste, mercury, gasoline, and diesel fuel into the forest waters. Some are equipped with military-grade weapons, and organized crime factions are involved in some regions—narco-mining. Moreover, the miners are advancing, since the Jair Bolsonaro administration seems intent on deliberate omission.

In March of this year, one hundred miners in search of gold reached the vicinity of this Yanomami woman’s village and anchored their six barges an hour from her home. A young man from the community went to the mining site with his wife. Their eyes on the wife, a group of miners goaded the man into drinking so much that he fell down drunk. “He was drunk, passed out. That’s why they screwed her,” she says. And the raping went on. A seventeen-year-old girl was enticed to one of the barges by another young Yanomami man, who was working there as a boatman. “He told her ‘We’re going to get a rifle for your father [to hunt with]; I want to get a motor [for a boat]!’” When the two of them reached the barge, the miners gave the girl some cachaça liquor—and one of them raped her. And then another did. And then another. “There were so many, like this,” she says, gesticulating a quantity she cannot count.

After this collective rape, the teenager’s family was given packages of rice, black beans, pepperoni, flour, and sardines. There is no one to report the crime to. Even if a formal complaint were filed, locating men who move in and out of the forest illegally, when and how they want, would be problematic. In a territory demarcated exactly thirty years ago and now under the constitutional protection of the Brazilian state, there are regions controlled by illegal mining forces where mining bosses have supplanted the state. During the nearly four years that Jair Bolsonaro has been in office, the situation has deteriorated further, as public authorities have failed to take any consistent or truly efficacious action. Under international pressure, the government has engaged in ostentatious one-time operations, during which they spend two weeks destroying machinery and aircraft. This yields good photo opportunities but changes nothing. Three such operations were conducted in 2021. This year saw only one, in early August, and the miners are already back.

The woman eventually asks us in her language, pain and outrage in her voice: “Why do the miners screw Yanomami women?”

Why? How do we respond to this question, asked by a woman who has been witnessing the destruction of her world ever since the first napëpë [white, foreigner, enemy] set foot in the forest? Where do we start?

The Indigenist expert and anthropologist Ana Maria Machado is accompanying me. She is among the few translators and interpreters of one of the six languages spoken by the Yanomami and has maintained close relations with some of their communities for fifteen years. She was asked to join the team because we were after precise words; we wanted to understand what the Yanomami people are experiencing, in their own terms. But even Ana was not prepared for what she heard and witnessed. Young girls she has known since they were toddlers have been raped and prostituted; teens she knew while they were growing up lure their friends into prostitution in return for cell phones. It is a world that is falling apart, and Ana knows these marks will remain even if the miners leave, because what is changing is a way of being forest and of being in the forest, as the great shaman Davi Kopenawa Yanomami makes clear in another article in this issue. Like the Amazon rainforest, the Yanomami may be approaching the point of no return. This ongoing process of extermination is not merely physical, produced by guns, disease, and contamination; it is the extermination of a way of life that planted part of the forest that is now being trampled.

We knew it would be extremely hard to reach the regions dominated by illegal mining interests because these criminals control not only the ground but also the air. They have information on everybody who arrives, and even healthcare teams have trouble providing services. We have watched the forest become a territory controlled by a kind of militia, much as what has happened in favelas and communities in Brazil’s big cities, such as Rio de Janeiro. We have seen Indigenous adolescents ensnared like the Black youths in urban communities, first by drug trafficking and then by militias, composed of former members of public security forces. This is happening now. Given the meager response on the part of public authorities, the main resistance has come from leaders like Davi Kopenawa, organizations like Hutukara Yanomami Association, and socioenvironmental activists.

Data we obtained under Brazil’s Access to Information Law indicate that healthcare hubs inside Yanomami territory have had to close their doors thirteen times since July 2020 due to threats to providers or armed conflicts, often instigated by miners in the territory. In Homoxi, miners kicked the healthcare team out and turned the place into an aviation fuel storage facility. Right now, five of the territory’s thirty-seven healthcare centers have shuttered their operations and have no providers. A total of 3,485 Indigenous people have been abandoned, left without medical care at a time of rampant disease.

When in urgent need of help, the Yanomami who have cell phones are forced to ask the miners’ permission to hook up to their internet hubs, installed by the criminals themselves. In despair, they turn to the Special Office of Indigenous Health (SESAI) for aid. The only helicopter assigned to provide the Yanomami with health assistance is sometimes out of commission, according to healthcare providers; meanwhile, dozens of miner-owned aircraft fly illegally through the skies, no problems. In the Xitei region, where the local healthcare post has been closed for five months—for the third time since mid-2020—official data show that seven children died from lack of medical care last year. In the Yanomami territory as a whole, 46 children under 5 lost their lives last year due to lack of diagnosis and treatment. According to Hutukara, in 2022, from the end of July until now, eight more children have died.

After the price of gold shot sky-high, criminal factions added this commodity to their illegal business portfolio and are advancing in regions like the Yanomami territory. They often count on the complicity of public employees and the support of a portion of the local elites, whose relationship with the forest is marked by predatory extractivism. While the Indigenous number twenty-eight thousand, there are some twenty thousand invaders, according to estimates by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)—and the figure for the miners is trending upward. Their weapons are capable of taking on the Federal Police and the National Public Security Force. The Illegal Mining Monitoring System, maintained by the Hutukara Yanomami Association within the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, has detected the presence of miners in areas affecting 273 of the 350 villages, impacting regions occupied by 56 percent of the Yanomami population.

What is left for the women, adult and child, the main victims of all wars? How can we begin to respond to the question asked by the Yanomami woman?

The woman is from the region of Missão Catrimani, an area that is part of Yanomami Indigenous Territory. It is not possible to reach the place she lives without jeopardizing our lives. Mining command now extends into this area as well and entry is restricted. In each region we had intended to travel to, people whom Ana Maria has known for over ten years warned us that if we entered, we might not come out. The Yanomami are under siege and their voices are increasingly silenced. We tried to figure out a way around this hurdle without falling victims ourselves— as happened to Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips, executed in June of this year in the Javari Valley, another Amazonian region invaded by organized crime. Ultimately, the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA)—one of Brazil’s largest NGOs—helped us fly witnesses and victims to Demini, the region led by the shaman Davi Kopenawa, where we could listen to their stories of what they were going through without running any risk. We launched a complex journalism operation in a territory under war—a war between such lopsided forces that a more precise term would be “massacre.”

We took another group of women to a house in the country, not far from the capital of Roraima, Boa Vista, a city where the main monument is a statue of a miner. There we asked the women to draw images of what they had heard, seen, and suffered. These are the drawings superimposed on pictures taken by the third member of the Sumaúma team, the photographer Pablo Albarenga. Since the women would have to return to the territory under criminal control, where they or members of their families or community might run the risk of execution, their identities had to be concealed. Pablo had the challenging mission of documenting in images the dramatic reality of life in Yanomami territory—without identifying the women. The solution was to juxtapose photographs of the women with their drawings. Each photograph in this story ties a woman to her personal interpretation of how illegal mining has affected her community. This is the image they reveal to the world, with faces they are forced to hide.

One of the women is wearing an old white T-shirt and short black skirt. At home, she always dresses in a wool loincloth and decorates her body with beads, but she is in the city for medical treatment right now. She makes a point of painting five red stripes of annatto paste across her face just minutes before her interview. This is a show of self-affirmation and affirmation of her indigenous identity, even though her full face cannot appear. Forest women use dye from this Amazon fruit to adorn and perfume themselves and also as sunscreen. Once the woman is ready, she does the opening drawing for this story: a nightmare sketched out as disproportionate-sized penises. She tells us she was pregnant five months earlier and had to be rushed from her village to a hospital in the city. “I lost the child in my belly. He was born dead in the hospital.” She shrinks into her chair. This is her third straight miscarriage in recent years. Before that, she had two children, now twenty and nine years of age. Such unwanted pregnancy losses are not common in the lives of women like her. Or at least they never used to be.

It is impossible to know exactly what caused the death of these women’s children without an investigation. But the mercury used in illegal mining operations to separate gold from the rocks can cause fetal malformation. “The metal contaminates aquatic animals and ends up ingested by people when they eat. Then it spreads throughout the body’s organs and tissues,” explains Paulo Basta, a researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz), one of Brazil’s leading health research institutes. In 2014, Basta led a study that detected elevated levels of mercury contamination in the bodies of Yanomami. Another Fiocruz study, released in August of this year, estimates that 45 percent of the mercury from illegal mining is being dumped into rivers in the Amazon without any treatment or precautions. In early 2021, researchers collected samples of fish from the Uraricoera, a river that passes through Yanomami territory and is one of the hardest hit by illegal mining. They found that six in every ten fish displayed mercury levels above those stipulated as safe by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Mercury poisoning can lead to hallucinations, seizures, persistent headaches, and visual and auditory loss. In addition to miscarrying, pregnant women exposed to the substance may give birth to children who present developmental delays. This damage will be felt by generations to come since mercury can remain in the environment for up to one hundred years. “What is happening with the Yanomami is an unprecedented public health and humanitarian crisis,” the scientist stated.

Here is another question we don’t even know how to begin to answer: Why was the woman who draws disproportionate penises condemned to have three miscarriages? Why is she condemned to fearing her next pregnancy as much as she fears the proximity of the men who possess the penises she draws? Who is going to keep these criminals from violating the bodies of women, rivers, and the forest?

A flight over Yanomami territory shows that the forest’s body is covered in open sores; its trees swallowed by huge muddy craters, brown encroaching on green. The image resembles the devastation left by an aerial bombardment. A single hole can extend over one square mile (2.5 square kilometers) of forest—to have a rough idea of this, imagine a patchwork of 422 official soccer fields. In August, the latest month for which data are available, illegal mining-related deforestation had reached seventeen square miles (44 square kilometers), the equivalent of nearly 6,000 soccer fields.

On the ground, this violence has an odor. “The water stinks,” says a Yanomami woman from the region of Parima. The miners are close to her village and throw their feces in the river where her community bathes, fishes, and gets their drinking and cooking water. “They crap in the water and we get diarrhea,” she reports. “When there weren’t any miners, we were fine. We’d catch good crab and fish, we drank very good water, but now it’s all gone bad. If they send [the miners] far away, if the water goes back to being clean, do you suppose the fish will taste good again?”

Fotografia: Pablo Albarenga, Desenhos: mulheres Yanomami

This wasn’t the first massive invasion of the Yanomami territory. In the late 1980s, 40,000 men spread across the region, bringing with them viruses, bacteria, and guns. Fourteen percent of the population was exterminated as a result. The main source of documentation on this era comes from the photographer Claudia Andujar, a central voice in denouncing the massacre of the Yanomami people to the international press. Xawara is the Yanomami word for the tidal wave of diseases that killed their people. The territory had not been demarcated yet, and the ensuing global uproar was decisive to ratification of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in 1992, seven years after the democratization of Brazil and four years after the country’s new Constitution recognized the rights of original peoples for the first time.

Davi Kopenawa—who lost his mother and part of his family to measles, a disease brought in years earlier by evangelical missionaries—became the voice of his people. The Falling Sky, co-authored by Kopenawa and the French anthropologist Bruce Albert, is a landmark text and a turning point in anthropology. The book is both the testimony of a shaman about the colonizing advance on the body of the forest and the body of forest beings as well as the testimony of a forest human about the climate collapse. Shamans hold up the sky, but shamans are being killed by napëpë and their xawara. Employing poetic expression consonant with the best science, Kopenawa shows how the action of the forest—this complex, high-tech being formed through constant exchange between so many other beings—is what “creates” the sky, that is, the earth’s atmosphere. If today’s accelerated destruction means the forest ceases to act as a forest, the sky will fall.

Following on the heels of 21 years of business-military dictatorship, which transformed the forest into a body open for predatory exploitation, the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory and democratization of Brazil represented the possibility that we might change how we treat both nature and the people who have never cut themselves off from it. But Brazil’s democratic governments were never able—or never wanted—to halt the destruction of the Amazon. In recent decades, the forest and its peoples have been attacked by illegal mining interests, large transnational mining concerns, agribusiness, logging companies, and grilagem (the theft of public lands), while they and their lands have also been usurped by major government projects like hydropower plants, highways, and railways. When Perimetral Norte federal highway was opened in 1973 under the dictatorship, prior to the mining invasion, once-sporadic contact with the Yanomami became incessant. Some Indigenous experts say the inauguration of this road signaled the beginning of a holocaust for one of the planet’s most complex cultures.

More than forty years later, Jair Bolsonaro, a notorious defender of the dictatorship, has magnified and accelerated the destruction of the forest at a moment when the climate collapse is triggering ever more extreme weather disasters, and he has done so with the collaboration of the current Congress, dominated by representatives of agribusiness and predatory mining. Bolsonaro, a prominent face in the new global far right, did his own illegal mining when he was in the army. After taking office as president in 2019, he oversaw the structural dismantling of the agencies charged with oversight of environmental crimes in Brazil, at the same time making public statements to incentivize exploitation of the forest. “For my part, I would open up mining. There’s a project to open up mining on Indigenous land,” he said in 2020. He had made his agenda abundantly clear during his campaign: “You can be sure if I get [to the Presidency], there won’t be any money for NGOs. If it’s up to me, every citizen will have a gun at home and not a single centimeter will be demarcated for Indigenous reserves or quilombolas [descendants of the enslaved rebels who settled in communities known as quilombos],” he declared at a public event. He has kept his pledge not to demarcate one more centimeter of Indigenous land, and Congress is currently studying the possibility of opening Indigenous lands to legalized mining.

During the pandemic, the International Criminal Court received official requests to investigate Bolsonaro for Indigenous genocide, based on the president’s actions. His veto of a measure to provide original peoples with potable water was among various decisions that hampered an effective fight against COVID-19 and resulted in the deaths of some of Brazil’s key Indigenous leaders—at least one of whom was the last elder of his people, the Juma. NGOs working to defend nature and its peoples were also driven from the forest by the pandemic, but the predators were not. Much to the contrary. The phrase “The destroyers of the Amazon aren’t working from home” gained circulation in a number of languages.

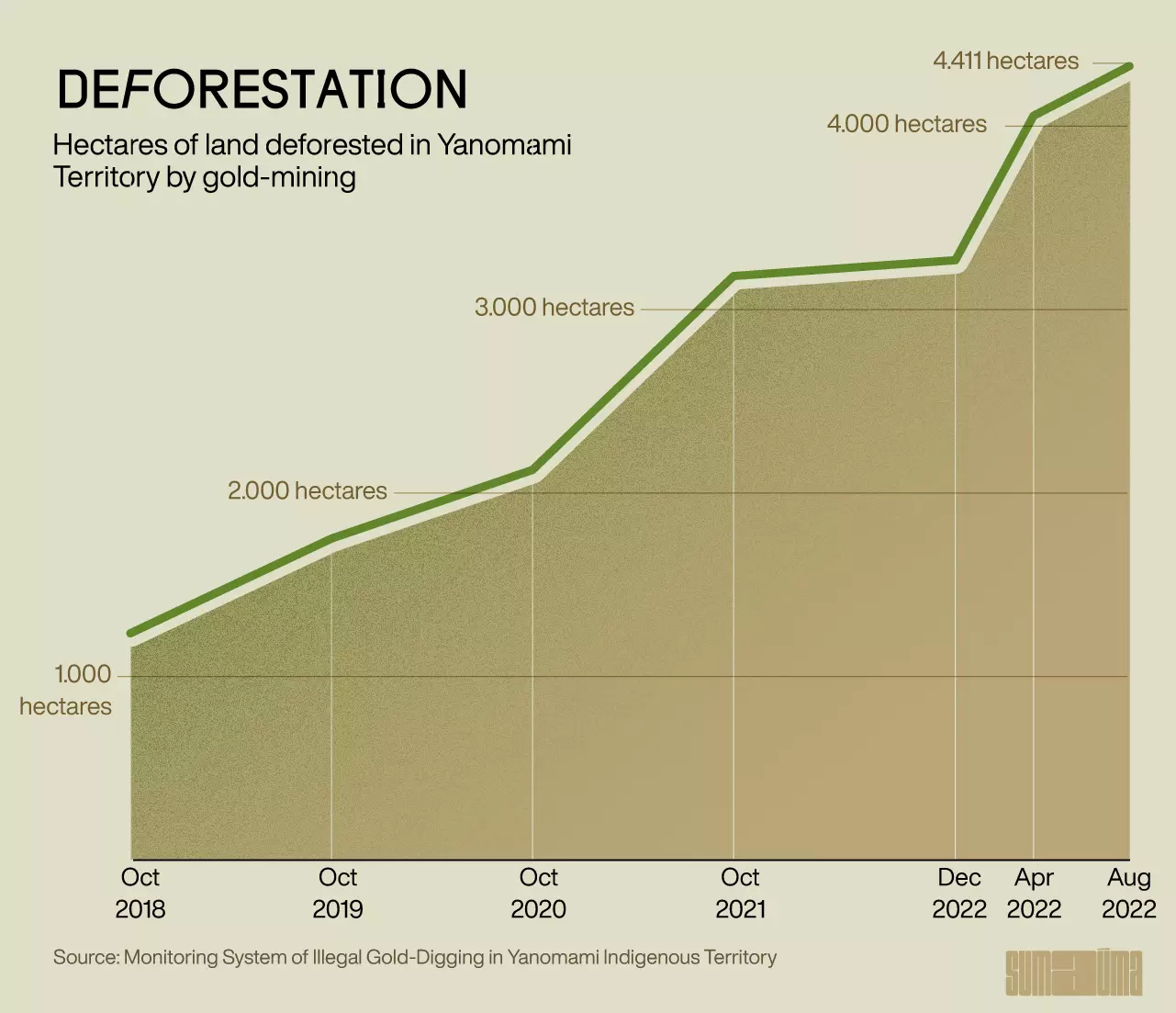

Pandemics like COVID-19 are linked to the deforestation of rainforests and other biomes because viruses previously confined to narrow stretches of woodland have lost their habitat, crossed boundaries and thus reached humans. In Brazil, the pandemic was used to expand destruction of the Amazon even further. In October 2018, two months before Bolsonaro was sworn in, the Hutukara project, which monitors mining-related deforestation, found that some 4.6 square miles of demarcated area had been devastated. By December 2021, almost two years after the first case of COVID-19 was reported in Brazil, this destruction had more than doubled, reaching 12.6 square miles (32.6 square kilometres). By August 2022, illegal mining activities had consumed another 4.24 square miles (11 square kilometres) of forest. Monitoring by the federal government indicates that in January 2022 alone, 216 deforestation alerts about mineral extraction inside Indigenous territory were issued, averaging nearly seven a day. There are even more alarming cases: in the region of Xitei, the deforested area soared 1,101 percent from December 2020 to December 2021.

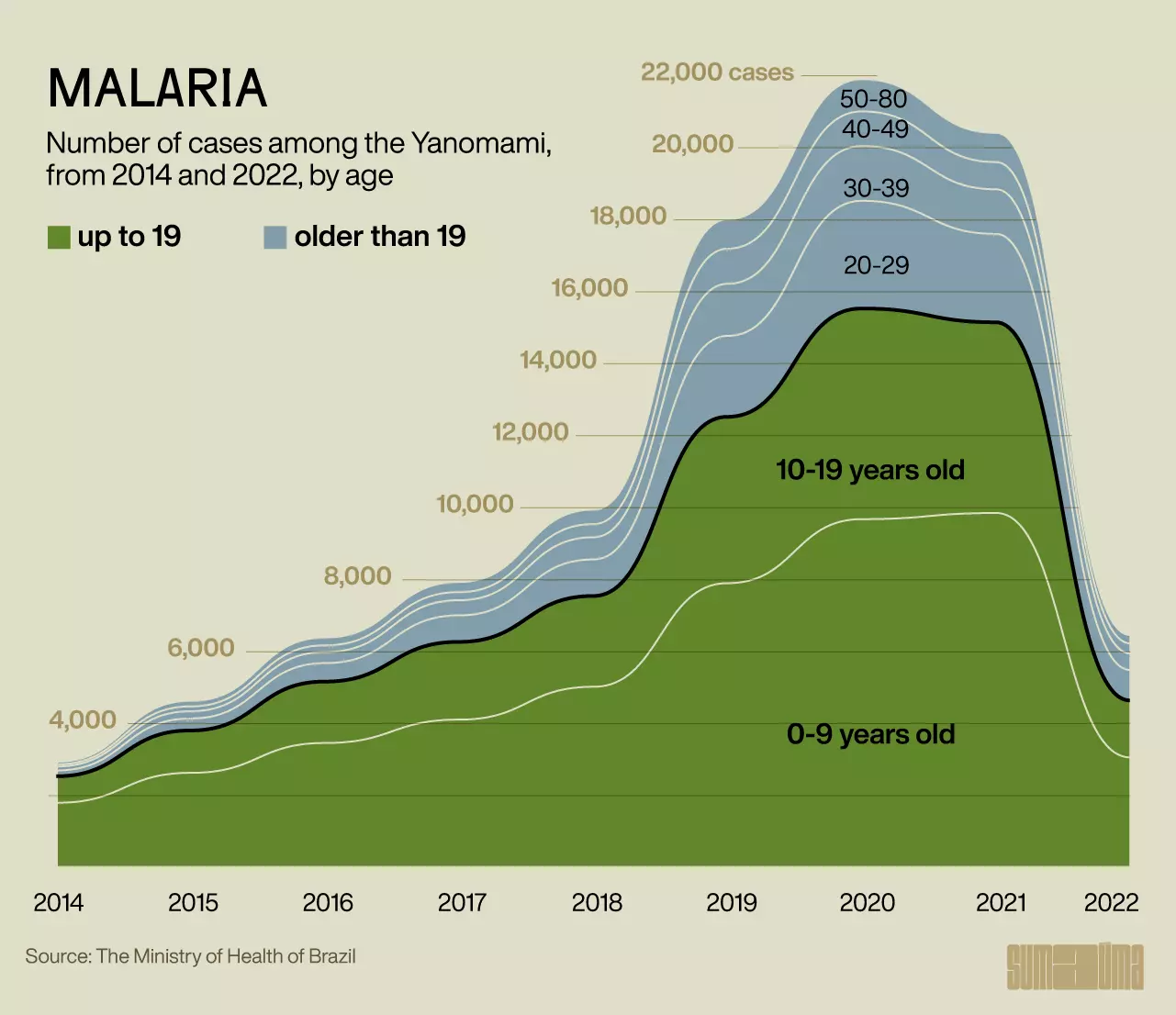

The incidence of malaria has risen sharply in Yanomami territory because miners act as vectors of various diseases. A woman from the Hakoma region crosses her arms over her chest, squeezes her eyes shut, and shakes her whole body to describe the plus-104-degree fever she had when she contracted the illness. She says she was “poremu,” meaning she was in a “specter state” because her vital essence was affected. She couldn’t do anything, not even get up out of her hammock. They medicated her in her village, and she recovered. A while later, she caught malaria a second time, her condition worsened, and she had to be taken to the hospital in Boa Vista.

From her home in the village, the woman listens all day long to the noise of the gold mining equipment inside the forest. “Pow-pow-pow-pow-pow-pow,” she says, pounding out with her fists a rhythm that is now part of their daily lives. The noise doesn’t stop even when night arrives. “Lots of planes land there. In the place where they’re digging holes, rifles, cartridges, bed linen, food, fuel, all those things are landed there,” she says. Data we obtained through Brazil’s Access to Information Law point to a steep climb in the incidence of this disease. From 2018—when the number of illegal miners in the territory skyrocketed—to 2021, cases of malaria rose 105 percent. While 2,928 cases were reported in 2014, the number surged to 20,394 in 2021. At least fifteen people died of the disease last year, ten of them children aged one to nine.

Brazil has run out of the medicine used to treat the disease, which is caused by the protozoal parasite Plasmodium viva. This information was admitted in a technical note by the Brazilian Health Ministry, signed in June of this year and obtained exclusively by the independent investigative journalism agency Amazônia Real. The medication in question is chloroquine, falsely touted by Jair Bolsonaro as an antidote to COVID-19 when taken at the onset of the disease. The lie spread by the Brazilian president himself not only conveyed a false sense of security during the pandemic but also led to a shortage of an essential antimalarial medication, aggravating the tragedy among the Indigenous. “The healthcare system has collapsed,” says Júnior Hekurari Yanomami, president of the Yanomami Indigenous Health District Council (CONDISI). “There’s no medication for worms, no chloroquine. Hunger is coming. Our history is being interrupted.”

Hunger and malnutrition come hand in hand with disease. In their traditional way of life, the Yanomami spend most of their time tending their gardens, gathering fruit and other forest foods, fishing, and hunting. When many of them fall ill at once, their garden produce is lost, and nothing is gathered. The contamination of fish and other river animals with mercury and other toxic substances has exacerbated food insecurity. When thousands of men invaded the forest, opening their camps by force, game animals disappeared. A people’s food system is being destroyed link by link, suddenly making their agelong way of life impossible. They are then forced to beg their tormentors for food, generally ultra-processed varieties. And always at an extremely high price.

“Our gardens were all flooded. There was a lot of water. Our cassava rotted. My grandson says he’s hungry,” another Yanomami woman tells us. “There’s no cassava, and so my husband and I went into town [to try to get government food assistance]. Our new gardens are still so small. All the children have lost weight, and it makes me so sad!” The woman lives in Palimiu, where deforestation grew 228 percent from December 2020 to December 2021. She also tells us the miners pump river water into the machinery that separates gold from rock and then discard the contaminated liquid in the forest.

In April 2021, a group of Yanomami from the settlement of Palimiu intercepted one of the invaders’ vessels when it was passing by the village and apprehended 261 gallons (1,190 litres) of fuel being transported to the mining site. Miners in another boat shot at the Indigenous. Nine other gun attacks followed through August of last year. During one of these confrontations, two children who were with their relatives got lost. They were found dead in the river, with signs they had drowned.

In other villages, however, miners have encountered no resistance. Men in the community are often the ones who invite them in. In the year 1500, when the first Portuguese invaders landed in Brazil, there was the classic swapping of trinkets, like mirrors, for gold. The same pitiful trading takes place now, more than five centuries later, in Yanomami territory and other regions of the Amazon. Indigenous youth ally themselves with the destroyers in exchange for the contemporary version of mirrors, anything from cachaça to cheap cell phones. More recently, the youth have also come to want gold. Davi Kopenawa often refers to whites as the “commodities people” because they like baubles and trade them for life. This taste for commodities is beginning to seduce Yanomami adolescents.

According to some reports, young Yanomami men are enticing newly menstruating young girls to have sex with miners in camp brothels. There are also growing reports of alcoholism among the Indigenous in mining settlements. The liquor is usually purchased with the money they receive for work with the miners. “When they want to buy cachaça [at the mining canteen], they buy it and come back drunk!” says one of the women we interviewed. These camps eventually turn into small settlements with a number of little stores and brothels. If the growth of these settlements mimics the colonization of Brazil and the state fails to block it, then small, completely illegal towns will soon exist inside Yanomami Indigenous Territory, an unprecedented affront to the Brazilian Constitution and international law.

One of the women we interviewed is actually still a girl. Her pink flipflops are a children’s size twelve (18 centimetres), typically worn by six-year-olds of normal height. Although she is eighteen, she is under four feet tall (1.2 metres) and speaks so softly it is sometimes impossible to understand her. She is in Boa Vista now but does not remember exactly how she got there.

The girl was living at an illegal mining site close to her village and sleeping on the verandah of a wooden house with three other Yanomami girls, two of them fourteen years old and one, thirteen. She says it was a brothel. A young man from her community persuaded her to run away from home, along with a female cousin, and she says she stayed for the food. Her fourteen-year-old half-sister had been taken there earlier. The girl would have sex with the invaders in exchange for rice, cookies, pasta, and sugar.

The non-Indigenous women slept inside, while the Yanomami teens hung their hammocks outside. The girl contracted malaria there. There was no help around; she lost consciousness and the miners abandoned her in her village. After her community called emergency services, she was flown directly to an intensive care unit in Boa Vista. And so she woke up alone in the city. A pink lollipop clutched in her hand, this small Yanomami girl does not admit she was prostituting herself; she just says the other women were. She has no idea condoms exist.

In the Demini village, the artist Ehuana Yaira Yanomami, who helped us out by interpreting other Yanomami languages, lives in a corner of the forest not yet reached by mining. The only photograph published here where the women expose their faces is the one of her and her two sisters. Ehuana listens to the sound of macaws and of leaves fluttering in the wind. She walks among trees she has known since she was a child, clearing the path with a machete to reach a stretch of river where fish still swim. She is accompanied by the women we have taken to this gathering, women from other regions laid waste by mining. Here they reencounter a lifeway that is slipping away; here they remember what has been torn from them. In the community, they organize a collective fishing expedition, using leaves from a woody vine known as timbo, gathered from their gardens. After crushing this toxic herb and mixing it with soil, they throw it into the river. Temporarily deprived of oxygen, the fish rise to the surface, where they can easily be caught. With their precise movements, these boys and men equipped with arrows and these girls and women carrying machetes and baskets guarantee their own food. They repeat the gestures of their ancestors, while the threat draws closer to Demini.

“When we wake up, a little before dawn, sometimes we think: ‘Do I need to dig up some cassava now, early? We don’t have any beiju [starch cake made from tapioca], we’re going to be hungry!’ Then we go dig some cassava. But first we eat a little, waiting for the day to get lighter. We eat a little bit of banana before we go out; we don’t go out hungry. When we go out to dig up cassava, we take our daughters; the men don’t go with us. Then we carry firewood home, so we can cook. This is what our thoughts tell us to do. If we want to go into the forest when we wake up, if we went to bed hungry and want to fish, we go into our gardens and pick some timbo leaves. We take the leaves and do our fishing. When we come back home with the fish, we cook it and eat it, and so our bellies are full and we lay down in our hammocks. After that, we go bathe ourselves and, at the end of the day, when it’s almost night, we feed our family again. If there’s any game meat, we eat a little.”

This is how the day goes, as narrated by a woman from Demini. Every day, she and other women from the village wear red wool loincloths that cover their sex; beaded necklaces crisscross their chests while their breasts hang free so their younger children can nurse whenever they want. Like almost all Yanomami women, they have an average of three to six children. They always go around with their youngest in a wool sling, held fast to their bodies, with their other little ones perpetually under foot.

Walking down the many paths through the forest near their community, these women know the name of every tree, plant, or insect. They hate it when they have to go into the city for health care, preferring the fresh air of the forest. Some have never left the woods. The forest is their home, food, medicine, water, light, and shade—a life that suffices because it is in constant exchange with everything alive. Here, families live together without any walls separating them. Chitchatting back and forth in their hammocks, the women roar with laughter. But they know their world is convulsing. And if it keeps on, the sky will fall.

There, in Demini, land of the shaman Davi Kopenawa, they are not at risk, not yet. But they are wary. Those who have come to tell them about the dangers advancing into the forest overwhelm them with omens. “In the future, the whites are going to finish us off,” says one of them. “The napëpë are ruining the Yanomami.”

The women of Demini look in fear at the visitors’ drawings of big moxi xawarapë—the Yanomami words for “diseased penises.” They know what the napëpë and their moxi xawarapë have reserved for Indigenous women. One of them says: “If the miners screw our asses, they’ll make us suffer. They’ll kill our children and screw our daughters.”

None of the women know how to respond to the question of why they screw Yanomami women, why they invade the forest and their bodies, why they rape them and the forest. Not a single answer, not even whispered. Only the napëpë understand this brutal mystery.

Editor: Eliane Brum

Yanomami translation: Ana Maria Machado and Ehuana Yaira Yanomami

Portuguese-English translation: Diane Whitty

Anthropological consultancy: Ana Maria Machado

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

* Sumaúma did this story with the support of the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA).

WHAT THE BOLSONARO GOVERNMENT SAYS:

The Fundação Nacional do Índio (Funai), the Brazilian state agency responsible for the protection of the country’s indigenous peoples, stated that the Yanomami territory has the support of five bases of ethno-environmental protection: Serra da Estrutura, Ajarani, Walo Pali, Xexena and Korekorema. “All of these units are responsible for permanent and continuous actions of territorial protection, investigation and surveillance, as well as curbing illegalities, controlling access, monitoring healthcare and other other activities,” they said.

However, the only one of these five bases that is not challenged by judicial action is Ajarani. The Federal Public Ministry (MPF) has launched lawsuits against the bases of Walo Pali, Serra da Estrutura and Xexena for failing to live up to their obligations. In addition, in March this year, federal justice authorities penalised Funai with a daily fine of 10,000 Brazilian reais ($1,900) for failing to reactivate the Korekoma base. Although Funai claims this base is operations, it is empty according to the prosecutor of the Republic Alisson Marugal, who is in charge of the Office for the Defense of Minorities’ Rights in Boa Vista. “Alongside healthcare centers and the Border Platoons of the Brazilian Army, the bases of ethno-environmental protection are the sole presence of the state in the Yanomami territory, and the only structures directed to the protection of the indigenous communities”, he said.

Funai insists its budget for the Yanomami Front of Ethno-environmental Protection increased 512% during the last three years, with around 3.4 million reais ($660,000) invested between 2019 and 2021, compared to 556,000 ($107,000) reais between 2016 and 2018. The foundation emphasizes that illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Land is a chronic problem “resulting from decades of failures of Brazil’s indigenist policy which, in the past, was led by underhanded interests, lack of transparency and strong presence of non-governmental organizations”, the organ alleged in a note.

“Against all of that, the new Funai has its activities guided by legality, legal certainty, pacification of conflicts, and the promotion of indigenous autonomy”, the office states. Marcelo Augusto Xavier da Silva, who took over the presidency of the organ during the term of Jair Bolsonaro, is a police chief and has been charged by the Public Ministry with administrative dishonesty. He has also been sued for failing to comply with judicial orders obliging Funai to further demarcate Munduruku Indigenous territory.

Funai states “many joint actions have been carried out together with environmental organs and relevent public security forces, especially in the Operational Plan of Integrated Activity of the Ministry of Justice and Public Security”. That operation, however, was only carried out after the Public Ministry legally obliged Funai to act. Last year, three operations were carried out, lasting around 15 days. This year, there was only one, in August.

“In 2021 and 2022, for instance, the operation Guardians of the Biome, supported by FUNAI, apprehended 147 aircrafts, 53.7 tons of ore (cassiterite, gold and mercury), 121,000 liters of fuel, 1,073 units of ammunition, 159 containers of gasoline and diesel, over 40 vehicles including ferries, tractors, cars and boats and 91 engines. Furthermore, inspections were carried out on 182 aircrafts, 87 airstrips, 135 retail posts, while 22 gas stations and 14 aircraft were suspended, 63 people arrested and 115 issued with notices of illegality”, says Funai’s statement.

“These operations last 15 days. They have very good results. But the miners re-establish themselves easily”, the prosecutor said. “The problem has grown to massive proportions, but it would be easy to fight back if there were a genuine effort. The government would have to deploy an aircraft for six months in order to suppress logistical hubs, as well as airstrips and inland ports. It is way easier to fight back against the strategic hubs than the mining sites within indigenous land”, he says. Usually, the stepping stones to mining activities are farms inside the forest, but outside the demarcated territory.

The Ministry of Defense and the Army, responsible for the surveillance in border areas like the Yanomami area that is close to Venezuela, affirmed in a statement that it performs specialized analyses to inform the actions of other public organs. Last June, the military launched the first satellites of Project Lessonia, which will provide images to support the campaign against illegal mining. Regarding claims of abuse against Yanomami women, the Ministry of Woman, Family and Human Rights affirmed the National Human Rights Commission is prepared to receive the complaints of traditional populations, including indigenous populations, and “has been acting continually to receive and forward demands from indigenous people and complaints of human rights violations that arrive at this organ”.

Translation: Thiago Leal