Brazil’s equatorial margin, the ocean region around the country’s northern coast, is extremely rich in fish and home to 80% of the country’s mangroves, while its currents and beds, especially in the basin at the mouth of the Amazon River, remain little studied by science. Yet in this extremely sensitive area, where fears abound over the possible consequences of an accident, the country’s state-owned petroleum company Petrobras is seeking to drill a well in search of oil, in so-called block 59, 159 kilometers from the Oiapoque region. Opposing interests within the Brazilian government have turned the project into a key test of the environmental commitments of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, and Brazil’s Environment Minister Marina Silva.

Case documents from Brazil’s environmental protection agency, Ibama, seen by SUMAÚMA, reveal the licensing process for the project is close to the point of no return. Pressure from Petrobras intensified during the death throes of the Jair Bolsonaro government, with the company choosing to overlook its own history at the mouth of the Amazon, where a drillship, while drilling, was dragged away by the current 11 years ago. Although an Ibama license will give the project the green light, the agency’s powers are limited, as it examines only the direct impact of a project on its immediate area, as though it were isolated from the wider socio-environmental environment. Often, then, an environmental policy ruling is required from the government, which is why the Petrobras project represents a direct challenge to Lula and Marina Silva – especially at a time when they are promising urgent efforts to save the Amazon forest from irreversible degradation, and after Brazil’s president has committed himself, even prior to assuming office, to delivering measures that seek to replace fossil fuels, to prevent global warming from reaching a catastrophic level.

When questioned by SUMAÚMA about the Foz do Amazonas (which means “Mouth of the Amazon”) project, Petrobras and Brazil’s Environment Ministry issued, through their respective press offices, responses which reveal the clash between the two sides.

Petrobras stated that, under new president Jean Paul Prates – a Lula appointee – it has no intention of abandoning drilling in the area. “The exploration of new reserves is essential to maintaining the oil and gas business, even in a scenario of energy transition which will naturally lead to the prioritization of clean energy sources. These exploration and production activities are carried out under strict social and environmental responsibility protocols, in line with the company’s Strategic Planning, and are submitted to external control from inspection agencies,” the company said.

The Environment Ministry, meanwhile, in a joint response with Ibama, drew attention to an extract from the agency’s most recent technical statement on the project, dated January 31, which states that “the absence of a strategic environmental assessment, such as the Sedimentary Area Environmental Assessment [an instrument established in 2012 that would allow for a broader assessment of the entire region affected by an oil industry venture], and other environmental management instruments, significantly hinder decision making on the environmental viability of the project, which is in an area of well-known socio-environmental sensitivity, and represents a new frontier for the oil industry”.

As the statement from the Ministry says, Petrobras’s proposed drilling in block 59 – up to an estimated depth of 2.8 kilometers – could represent the opening of a “new frontier” for oil for the company. The decision whether or not to grant the license, which would potentially open up a flood of permits, lies at the heart of the region’s future, the fate of the forest, and also of Petrobras itself: will the company remain focused on oil exploration for short-term gains for shareholders and government coffers – what a specialist from the Lula government’s transition team called a “kamikaze strategy” – or will it use its technical capacity to focus on the green fuels that will dominate beyond 2030, including biomass, green hydrogen and ocean wind farms?

Suely Araújo, who chaired Ibama between June 2016 and December 2018, and is now a public policy specialist at Brazil’s Climate Observatory (a network of civil society organizations interested in the protection and conservation of the environment), says an oil spill in the Foz do Amazonas region would cause a tragedy. “Petrobras should be using areas that have already been opened up, rather than investing in new explorations of ecologically fragile areas,” she says. “Under the Bolsonaro government, they tried to obtain a license for an area close to Abrolhos, near Fernando de Noronha, and at Atol das Rocas. The mouth of the Amazon region hasn’t been studied, nobody really knows what kind of biodiversity there is, while its characteristics, with the great quantity of sediments from the river, are unique around the world. What’s really there? We have clues, but we don’t know for sure.”

AN OIL SPILL IN THE REGION OF BLOCK 59 WOULD PUT NATURAL ECOSYSTEMS SUCH AS THE AMAZON REEF AND THE MANGROVES OF FRENCH GUIANA AND BRAZIL AT RISK. PHOTO: ELSA PALITO/GREENPEACE

The Great Reef

Edmilson dos Santos Oliveira, of the Karipuna people, is coordinator of the Council of Chiefs of the Oiapoque Indigenous Peoples, which has 67 members. He, like other parentes (the Portuguese word for familial relative, used by indigenous people to refer to one another), fishermen and women, environmentalists and federal prosecutors in the field of the environment, is upset and uncertain about what could happen to Oiapoque, a region of mangroves and flooded lowlands that is home to three indigenous territories and two national parks and environmental protection areas.

“Petrobras’s projection doesn’t show the oil slick reaching indigenous territories, it just shows it going towards the French [Guianese] side. It’s unbelievable, because we know that, from the moment the tide turns, the tide rises, and the current comes towards and into the rivers. We’re very concerned, because our rivers are full of floodplains and açai groves from which we make a living, and lakes. If there’s an accident, we will lose a great deal,” he says. “All this is our life. Without the river, we don’t exist.”

Edmilson is referring to one of the most controversial points of the environmental licensing process currently in progress at Ibama. The scenarios for an eventual oil spill provided by Petrobras do not include the possibility of the oil reaching the Oiapoque coast. Instead, the scenarios are based on the strength of the North Brazil Current, which tends to carry spilled oil to the waters of French Guiana, Suriname and Guyana, even reaching Caribbean islands such as Martinique, Trinidad Tobago and Grenada – an alarming prospect in itself.

While recognizing the premises behind such a hypothesis, people from the region, like Edmilson and oceanographer Ricardo Motta Pires, head of the Cabo Orange National Park, which protects the ecosystem at the mouth of the Oiapoque River, have grave doubts, stemming from their experience on the ground. “In Cabo Orange, the tidal range averages 4.5 meters. There is an island to the south, Maracá-Jipioca, another protection area, where the tide reaches 11 meters. For comparison, in the southeast of Brazil, it’s about one meter. The terrain is soft mud, which can go up to your knees. The vegetation is siriúba [a type of tree], which breathes through millions of tiny surface tubes. If a slick reaches the coast at high tide, it will travel over a kilometer inland. When it settles, it will be the end of the mangrove. There is no way to clean these tubes, or recover anything,” says Ricardo, who has been in charge of the park for 20 years.

Because of this and other concerns, the licensing process, initiated by the British company BP, which controlled operations in block 59 until 2020, has been dragging on for nine years. Petrobras, which subsequently took over the operation (although BP remains a partner) sought to accelerate the process in the second half of last year. Ibama – responsible for licensing all oil exploration projects on the Brazilian coast – is currently close to setting a date for the so-called Pre-Operational Assessment of the Individual Emergency Plan submitted by the company, in which it demonstrates its ability to manage accidents. If the simulation passes the test, the approval of the Individual Emergency Plan occurs almost automatically, paving the way for the issuing of the operating license. At a meeting between the two sides on January 31, Petrobras proposed scheduling the Pre-Operational Assessment before Carnival begins on February 17, but Ibama said it considered this “unfeasible”, as the company’s Individual Emergency Plan has yet to be approved.

The equatorial margin is divided into five basins, starting in Rio Grande do Norte and reaching as far as Foz do Amazonas. Of these, the exploration of oil is only being carried out off the coast of the northeastern state of Rio Grande do Norte. At Foz do Amazonas, previous drilling in shallower waters failed to find oil. In 2011, in a warning of the risks of exploration in the region, a Petrobras drillship was carried away by the current when trying to find oil 110 kilometers off the coast of Oiapoque. The company ended up abandoning the well.

In 2013, just two years after the accident, Brazil’s National Petroleum agency conceded nine blocks in the Foz do Amazonas basin. So far, none has obtained a license to operate. In 2018, the French company Total, which had been seeking to drill in a block close to number 59, withdrew from the basin, after failing to obtain a license from Ibama – in an area where the winds are always strong and the north current runs extremely fast, it had been unable to demonstrate it could contain an oil spill. At the time, Total found itself under great pressure from environmental groups, as well as facing new European Union directives to reduce the use of fossil fuels.

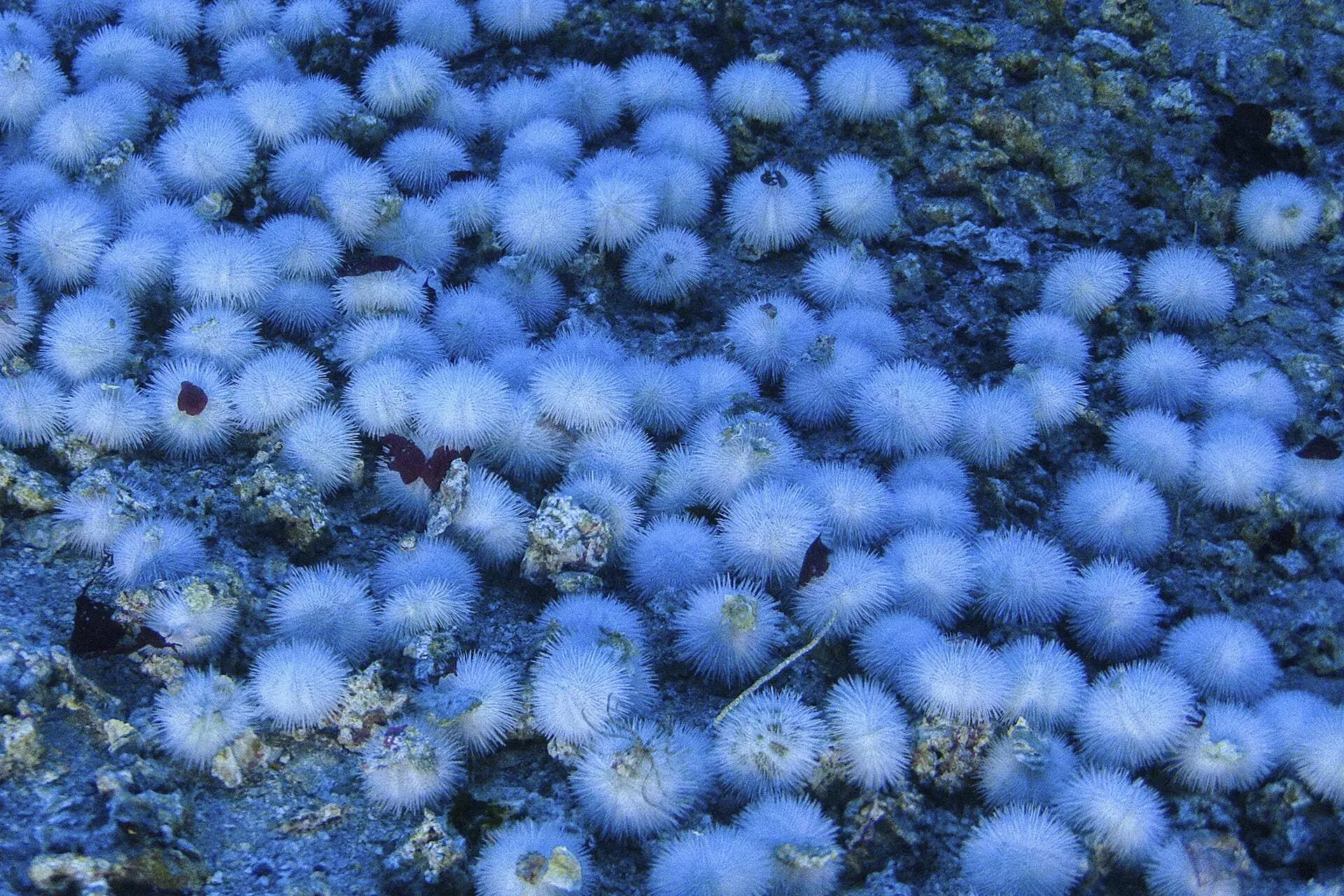

Additionally, in 2018 a Greenpeace expedition took previously unseen images of what scientists call the Great Amazonian Reef System. Around 200 kilometers from the coast, the formation was described in detail for the first time in 2016. It contains sponge banks and deep-water corals, where the “Amazon plume”, as the feather-shaped area of the sediments released by the river is known, permits light to enter. While its size and structure are still being debated by the scientific community, this reef system is another major concern for environmentalists, who are calling for more studies of the region.

WHITE SEA URCHINS AND RHODOLITHS (CALCARE ALGAE) FOUND IN THE AMAZON REEF ON THE COAST OF AMAPÁ. PHOTO: GREENPEACE

“The richness of the area’s fish population is due to the combination of the Amazon estuary and the great Amazon reef system. The carbon capture of this ecosystem is still the subject of academic study,” said biologist Vinicius Nora, a senior conservation analyst at WWF-Brazil. “In such a scenario, with numerous gaps in knowledge and a number of factors of socio-environmental importance, we must question whether it is the right place to advance the frontier of oil exploration, at the end of its time [as a resource].”

In the second half of 2022, when Petrobras presented its strategic plan for the years 2023 to 2027, the company planned to spend half of the six billion dollars (about 30 billion Brazilian reais) allocated for the discovery of new oil deposits in the equatorial margin. The idea set out in the plan was to drill 16 wells in the region, a large number compared to the 24 planned for the already in production pre-salt region [an offshore reserve below a 2,000m-thick layer of salt off Brazil’s southeastern coast].

The motivation behind the greed for the north coast region of Brazil is the experience of Guyana, a country of 800,000 inhabitants next to Venezuela, where large deposits were discovered in the sea by the American company ExxonMobil, from 2015 onwards. In neighboring Suriname, reserves were also discovered, though not on the Guyanese scale, and the start of oil exploration at sea was postponed to 2027. In French Guiana, there was a sequence of failed drillings, and Total suspended its operations in 2019. France’s decarbonization plan banned fuel exploration fossils from 2040, with the country already making extensive use of nuclear energy, controversial in itself.

Aside from financial and logistical calculations, Petrobras frequently cites its expertise in disaster prevention. However, when it comes to oil, a single accident can have lasting consequences, poisoning fish, birds and plants. To cite just one example, in 2000, a leak of 1.3 million liters from a pipeline at the Duque de Caxias Refinery spread over 40 square kilometers and contaminated the entire mangrove of the inner part of Guanabara Bay. Despite the effort to recover the area, almost 20 years later there were still oil deposits in the mud.

ROCKET REMAINS FOUND IN CABO ORANGE NATIONAL PARK, IN THE OIAPOQUE REGION: A SIGN THE CURRENT CAN CARRY AN OIL SPILL TO BRAZIL. PHOTO: PUBLICITY/ICMBIO

Chasing the rocket’s tail

In early November 2022, Petrobras acted to remove what has been the main obstacle to obtaining an operating license for block 59: the prediction of oil dispersion scenarios in the event of an accident. The “modeling”, as the computer-based study that underpins the Individual Emergency Plan is called in technical jargon, was delivered to Ibama by BP in 2015.

BP’s modeling was questioned by the agency. In a number of documents, Ibama states that the creation of a “hydrodynamic base” (or hydrodynamic modeling) was needed to obtain a precise scenario, which more accurately represented the coastal dynamics of the region, including the possibility that currents other than the North Brazil Current would carry oil residues to the coast of the state of Amapá. Such a modeling has not yet been completed.

In March last year, 28 environmental and indigenous organizations petitioned the Brazil Attorney General’s offices in Pará and Amapá, asking for the Public Prosecutor’s Office to intervene at various points in the licensing process. In the document, they referred to a study by researchers from the Institute of Coastal Studies at the Federal University of Pará, which notes five weaknesses in the 2015 modeling.

Among other concerns, the study states the projection used “outdated” nautical charts and failed to detail areas which were not relevant for navigation. It also says the projection fails to consider the complexity of the local coastline, “which has indentations, estuaries and mangroves with widths ranging from 100 meters to a few kilometers.” And it points out that, in this type of system, the tidal currents that flow towards the coast are more efficient at “pushing” materials from the sea to the land than the currents that flow from the land to the sea, and carry materials in the opposite direction.

The University of Pará study is echoed by the experiences of Ricardo Motta Pires, the head of Cabo Orange National Park. He recalls how in April 2014, his team was told the “remains of an airplane” had been found in the mangrove. After a five-hour search, supported by firefighters, they found several pieces of a rocket, which was later confirmed to have been launched the previous month from the Kourou Space Center, in French Guiana, from where the majority of European satellites are launched. In this type of launch, parts of the rocket that carries the satellite into the Earth’s orbit become detached on its journey.

According to Ibama itself, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, which manages the park, consulted with its partners in French Guiana, who estimated the rocket debris fell in an area 350 kilometers east of block 59, far from the coast of Oiapoque. “If we assume this part fell there and reached the park, it’s because of the current that carried it to the coast. Normally it would have floated to Guyana and Suriname, so there must be a current that forms and disperses, appearing only from time to time. This is the big question mark over what they [from Petrobras] have presented,” says the oceanographer.

He says that, during his time in charge of the park, he came across a boat from a rowing competition between Dakar, Senegal, and Cayenne, whose occupant had fallen ill and been rescued by helicopter. He has also found drift buoys for scientific studies launched in the state of Maranhão.

Despite such concerns, the Ibama documents seen by SUMAÚMA reveal the agency agreed not to wait for the creation of the “hydrodynamic base” to advance the licensing process. In an online meeting in September last year, the Petrobras representative appeared to take it for granted that the creation of a completely new model for the potential dispersion of leaked oil from block 59 would not be required. Instead he promised to provide a complementary study, with more up-to-date information about the maritime area, anticipating there would be no “major changes” in relation to the document presented by BP in 2015.

In fact, the study that Petrobras describes as “complementary modeling”, finally presented in November last year, states “there were no significant changes” to the environmental risk analysis. The document reiterates that no spilled oil would reach the Brazilian coast, though admits that without rapid containment action, it could reach the coasts of neighboring countries in ten days. “Petrobras confirms the new modeling results corroborated the behavior indicated in the previous study, that is, they confirmed the trend that the dispersion of an eventual oil spill would follow a northwesterly flow, influenced by the North Brazil Current, consequently moving away from the Brazilian coast, and flowing towards international waters, with a time to landing on the coast of countries neighboring Brazil greater than 10 days,” says the document, concluding that the assumptions of the Individual Emergency Plan, “remain accurate and do not require technical adjustments.”

At the end of January, Ibama issued a technical statement on the “complementary modeling”, which even mentions the rocket found in Cabo Orange Park and asks Petrobras to clarify certain questions. However, it also states such questions do not “at this moment impede the approval of the new study.” The opinion also refers to the licensing process for other blocks, including 57, which neighbors 59, recommending they wait for the updated modeling suggested by the agency, “especially as it is an extremely sensitive, little-studied area, with major logistical challenges, both for emergency situations and routine activities.” In the near future, Ibama’s analysis states, the “hydrodynamic base” for the equatorial margin will be ready, “opening the way for further improvements.”

Suely Araújo recalls how, in 2018, the Total project failed to receive a license because, among other reasons, the company was unable to prove it could prevent the arrival of oil in the waters of French Guiana. “In less than six hours, according to the report, the oil had already left Brazilian waters. You’d be opening up an area that will interface with another country. Imagine if it leaks. What would happen?” she asks. In the case of block 59, Petrobras calculates the oil would arrive in the waters of the French territory in ten hours, and says meetings took place last year with representatives of both it, Guyana, and Suriname. Although the Brazilian company did not report what was agreed at these meetings, Ibama considered the requirement of “communication with other countries” to have been met.

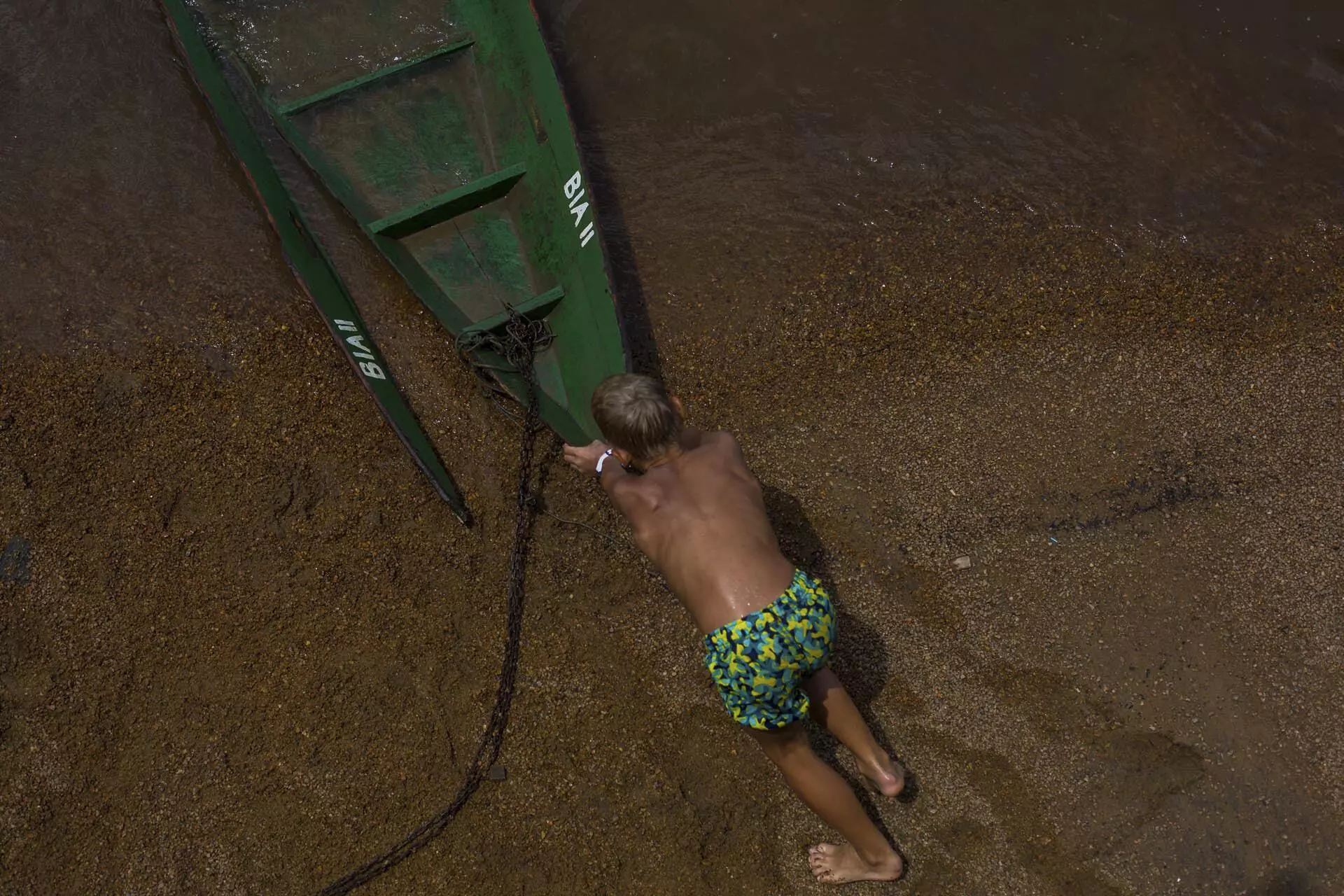

A RESIDENT OF CABO ORANGE NATIONAL PARK AND HER SON, IN THE OIAPOQUE MUNICIPAL REGION: OIL EXTRACTION CAN HARM BOTH A WAY OF LIFE AND THE ECOSYSTEM. PHOTO: DANIEL BELTRÁ/GREENPEACE

Manufacturing expectations

The preparation of Petrobras’ strategic plan for this year and next coincided with the intensification of the company’s presence in the city of Oiapoque. At the September meeting, the company presented a timeline which showed it expected to obtain its operating license by November. In December, it sent a drillship, the ODN II, to the region and even announced in the media that an emergency situation simulation would be carried out later that month. At the time, Rafael Chaves, Petrobras director of institutional relation, told the Diário do Amapá newspaper that “The dialogue with Ibama is great. With the Ministry of the Environment too. Everyone understands the importance of this for the region in terms of job creation, income generation, and increased investment.”

Ibama’s licensing protocol in relation to communications states that applicant companies must avoid generating expectations among the populations of areas of potential ventures. But declarations like that of Chaves – likely to leave the Petrobras board now the company is under new management – show why unrealistic expectations flourish in the region. Between October and November, the company held “informative meetings” in 18 municipalities in Amapá and Pará, including two larger hearings, one in Oiapoque, where it plans to install the project’s air base, and another in Belém, where the naval base would be located. At such meetings, in which Ibama officials took part, there were frequent questions about jobs, the training of local personnel and the payment of royalties.

The Petrobras spokespersons present, however, were more reticent. They said it would only be possible to talk about royalties and personnel training during the production phase, if oil is found. But, they added, the refurbishment of the local airfield by the company, which is already underway, will be “a legacy” for Oiapoque. The small airport, however, has already caused an impasse: the city’s landfill site lies on the route of the aircraft that would take work crews to block 59, and the original plan was to remove it. The replacement site chosen, however, is close to a village and a number of streams that are breeding grounds for fish. The case has yet to be decided.

“The arrival of Petrobras has generated great expectations for the city, they say it will bring wealth, improvements, employment. There are a lot of people, a lot of businesspeople, getting prepared,” says Cacique (Chief) Edmilson. “We get looked at and spoken about badly, too, ‘because indigenous people are against progress’. But we try to make it clear indigenous people aren’t against progress. What we want is to find a way to avoid risk.”

Also in relation to expectations in Oiapoque, Ibama’s most recent technical report on the licensing process, dated January 31, includes a number of unusual considerations, which may be interpreted as a request for help from the Environment Ministry. The text laments that the requirements of the environmental licensing process do not include mandatory assessments of the suitability of an oil production chain in the region where the project is to be carried out. The licensing process “is not capable of assessing the socio-environmental transformations caused by the installation of a group of ventures. It cannot predict whether oil is a suitable economic vocation for the region, compatible with its other vocations. Therefore, it is not capable of answering a fundamental question: is a certain region suitable for the development of oil exploration and production, considering the entire chain involved? And under what conditions?”

THE ARRIVAL OF PETROBRAS IN OIAPOQUE ALMOST MOVED THE CITY’S LANDFILL CLOSE TO AN INDIGENOUS VILLAGE AND STREAMS HOME TO FISH BREEDING GROUNDS. PHOTO: VICTOR MORIYAMA/GREENPEACE

Fishing to eat

Of the 28,000 inhabitants of Oiapoque, around 8,000 are from the Karipuna, Palikur, Galibi Kali´nã and Galibi-Marworno peoples. The three indigenous territories – Uaçá, Juminã and Galibi – represent 23% of the territory of the municipal region. Many of the 53 villages had to move because of the construction of the BR 156 highway, which connects Macapá to Oiapoque, a distance of almost 600 kilometers. Four major rivers dictate life in the region: in addition to the Oiapoque, there are the Uaçá, the Urucauá and the Curipi. In 2017, a bridge over Oiapoque was inaugurated, connecting the city to French Guiana.

Edmilson lives at Km 50 of the highway – his village was one of those relocated during the road’s construction. Now, its 75 residents live in houses of bricks and mortar, but only have electricity at night, when they can communicate via WhatsApp. The location is next to a branch of the Curipi River: there are plenty of fish, but no commercial fishing or hunting. “For dinner we eat the fish leftover from lunch, or catch more,” says Aniceia Forte, Edmilson’s wife. If someone kills a paca, an agouti or a tapir, they share it with other families. Only the surplus from the fruit and vegetable plantation can be sold, and the most common commercial activity is the production of flour. “We sleep peacefully at night, and don’t lock our doors during the day,” Edmilson says.

Which explains why there is concern about the arrival of people from outside, not just Petrobras employees, but “other adventurists seeking a better life”, as Edmilson puts it. When these expectations are frustrated, such individuals can turn to crime, as is often the case with major engineering projects. Lília Ramos Oliveira, or Lília Karipuna, elected two years ago as the first and only indigenous person among Oipoque’s 11 councilors, said the indigenous people organize themselves into “cleaning teams” in the reserves, to monitor illegal fishing and wood removal. Lília, from Brazil’s Republican party, said last year there had been signs of an invasion of illegal gold miners, who were trying to attract people from the villages, before the communities successfully persuaded the police and Funai, Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs, to take action.

THE OIL INDUSTRY REPRESENTS A THREAT TO THE ENVIRONMENT AND THE WAY OF LIFE OF TRADITIONAL POPULATIONS IN OIAPOQUE, IN THE STATE OF AMAPÁ. PHOTO: VICTOR MORIYAMA/GREENPEACE

No prior consultation

The petitioning by environmental and indigenous groups in March 2022 resulted in federal prosecutors in Pará and Amapá issuing a “joint recommendation” to Ibama and Petrobras in September 2022. In the document, three prosecutors requested the suspension of the Pre-Operational Assessment and operating license in block 59 until a new oil dispersion modeling was presented.

The prosecutors also mentioned the need for “prior, free, informed and good faith consultation with interested indigenous peoples and traditional communities”, in which “the consultation and consent protocols prepared by the impacted communities themselves” must be observed. In 2019, the four indigenous peoples of Oiapoque formally requested these consultations, provided for in Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, signed by Brazil and incorporated into domestic legislation in 2003.

In its response to the recommendation, Petrobras minimized the impacts of the first phase of the venture, claiming it simply intends to drill a well to discover if oil is present, and to assess whether it is worth exploiting, a process that could last more than a decade. If the decision to exploit the deposit is taken, said the company, it will need to obtain new production licenses. It is known, however, that, once the prospecting license has been granted, further exploration and production will be very hard to stop.

In the same response, Petrobras stated the possibility of oil arriving on the Brazilian coast had not been foreseen as the models do not carry out “reverse simulations” – that is, they do not outline scenarios of action based on hypotheses not foreseen by the models themselves. The company described the need for prior consultation, meanwhile, as “a stage already overcome”, as in 2016, when BP was in charge of the project, meetings were held with the indigenous and quilombola (residents of settlements originally founded by escaped enslaved peoples) communities of Amapá and Pará. “A few public hearings with the local community do not represent prior consultation, which should be carried out with each specific community,” says prosecutor Gabriela Tavares Câmara, one of the signatories of the Public Prosecutor’s Office’s recommendation.

While provided for in Brazilian legislation, Ibama does not consider prior consultation a requirement of environmental licensing. For the Council of Chiefs of the Oiapoque Indigenous Peoples, however, it is a question of rights and honor. “We demand consultation in any project that passes through or is developed close to indigenous lands” says Cacique Edmilson, who addressed the matter at a meeting with Brazil’s Minister of Indigenous Peoples, Sonia Guajajara, at the Funai headquarters in Macapá in late January. “They claim that for now it’s just a test to see what they find, but we’re concerned, because after the test they won’t carry out the consultation, they’ll go ahead and forget about it,” he adds. The impasse will be discussed at a meeting between indigenous representatives and Petrobras scheduled for February 14, after a meeting in December had to be postponed due to a Covid-19 outbreak in the Uaçá Indigenous Territory.

IMAGE OF THE DRILL SHIP ODN II, SENT BY PETROBRAS TO THE OIAPOQUE REGION TO DRILL A WELL AND SEARCH FOR OIL. PHOTO: PUBLICITY/FACEBOOK (OCYAN)

A growing impasse

After presenting its “complementary modeling”, Petrobras’ next step, in early December, was to announce the inclusion of four chartered ships – the C-Warrior, the C-Viking, the MS Virgie and the Corcovado – in its accident response plan. A fifth vessel, the Mr Sidney, had previously been inspected by Ibama in Rio de Janeiro and was considered fit for use on December 6. Yet just 11 days previously it had failed its first simulation of oil containment exercises.

The four new ships were inspected on the outskirts of Belém in mid-December. On January 24, Ibama delivered the inspection reports for the ships and the “advanced emergency base” in Belém: all were considered fit for the purposes of the Individual Emergency Plan, but the agency recommended more training for their crews, as well as the addition of supplies of spare equipment, requesting that any pending issues be resolved “before the eventual undertaking of the Pre-Operational Assessment”. In January, economic news agencies reported that Petrobras was spending a fortune, estimated at 5 million reais (around 985,000 US dollars) per day, on equipment used in the region: the drillship, three helicopters and the five emergency plan ships.

In the last few days, Petrobras has told the press the main pending issue for Ibama’s issuance of the operating license is the granting of a license for a De-oiling and Rehabilitation of Fauna Center, based in Belém, which must be done by the Secretary of Environment of Pará – a state governed by Helder Barbalho (of the Brazilian Democratic Movement party), who chairs the Legal Amazon Consortium and seeks to project himself as environmentally responsible, seeking to obtain financing to combat deforestation and produce green energy in the state. The center was initially to have been built in partnership with the Federal Rural University of Amazônia, but the partnership stalled, and a private company, Mineral, was contracted. The Secretary of the Environment for Pará has reported that the licensing request was filed in October, and that it has up to six months to analyze it. On January 19, it requested additional information from Petrobras. Ibama has scheduled an inspection of the center for February 14.

However, the modeling scenarios, including the potential repercussions in neighboring countries, are still considered the biggest obstacle to the licensing of the operation. In basic terms, there is little confidence in either the route an oil slick would take, or the argument that Petrobras would be able to control such a slick in the area of block 59. The transition in government will also play a part in any decision: in the next few days, the new president of Ibama, biologist and congressman Rodrigo Agostinho (of the Brazilian Socialist Party), will take office, followed by a director of licensing that he and minister Marina Silva will appoint. It is thought unlikely an interim director will be able to make such a delicate decision.

“I doubt I’d last more than a month at Ibama by saying no to everything seeking a license in Foz do Amazonas, but I’ve a feeling that’s what I’d do,” says Suely Araújo. “It is a difficult, complex, ecologically sensitive region. Just because something generates income for somewhere doesn’t justify the impact caused. It’s almost a curse, because the exploitation eventually comes to an end and everything goes back to the way it was. You create a dependency that will end at some point, and the prospect is that will be soon. Does Brazil want to be the last big oil trader in the world? Does it want this kind of headache? This kind of embarrassment?”

Translated by James Young