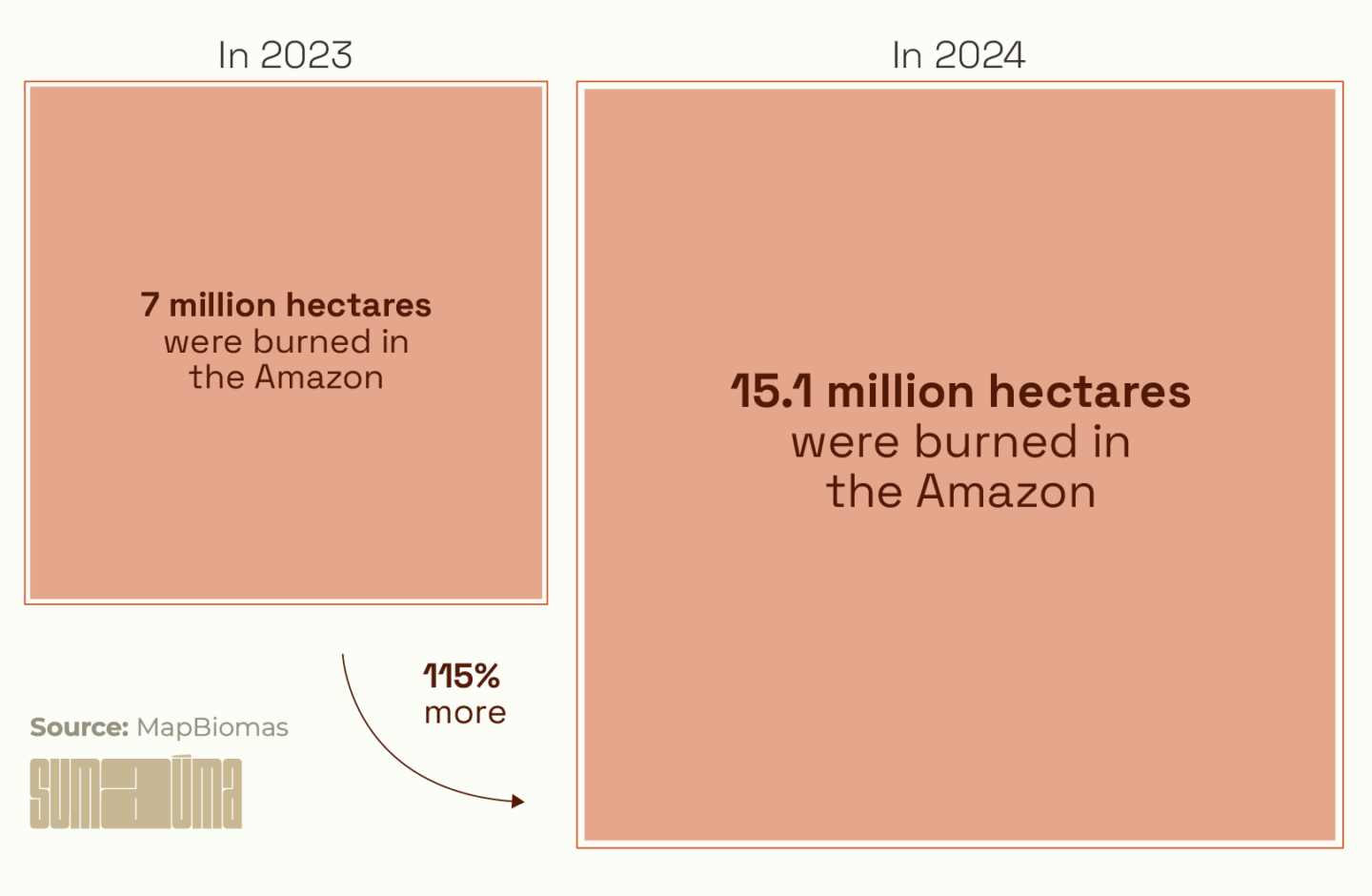

The area burned in the Brazilian Amazon in the first ten months of this year would cover a space equal to 100 times the size of São Paulo, Latin America’s most populous city. From January to October, over 120,000 fires destroyed 15 million hectares in the biome, according to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research. Despite a record number of blazes and certainty that human action is what caused them, only a few dozen people have been arrested, as found in a SUMAÚMA survey of federal and state police departments. There are cases like São Félix do Xingu, Pará. In this municipality, which holds the country’s largest herd of cattle and the record for most area burned in 2024, nobody has been punished for a single fire thus far.

The numbers illustrate how weak the laws are and how difficult and insufficient the investigations are in the Amazon, leading crime to continue rising. This year, the area lost to fire in the Amazon grew by at least 114% compared to 2023, according to the MapBiomas organization’s Fire Monitor. Police, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, and environmental authorities have a hard time obtaining evidence that would lead to a criminal prosecution of the people behind the fires. And when this happens, forest arsonists receive a slap on the wrist: their entire sentence can be served with work release or in home confinement.

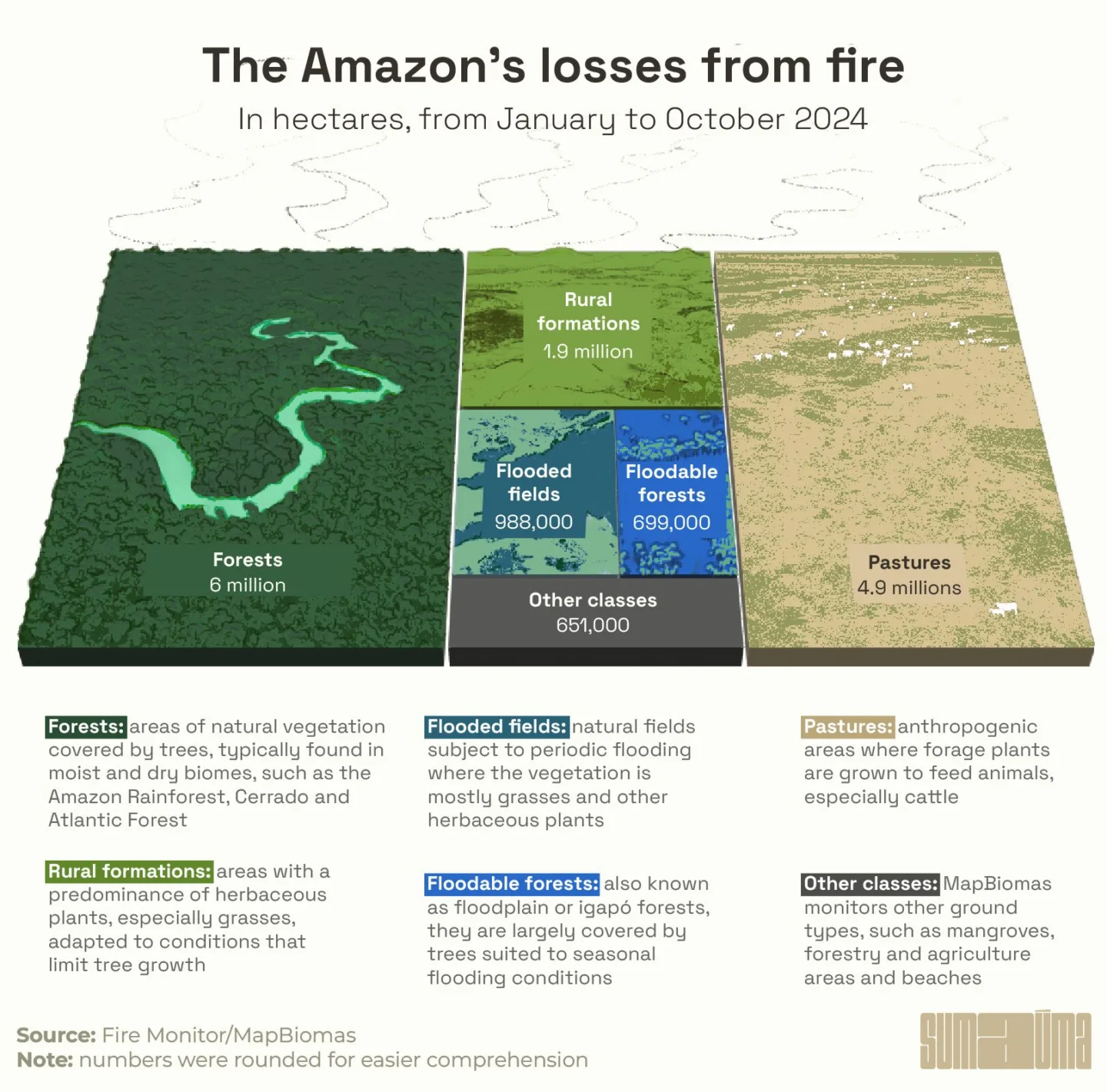

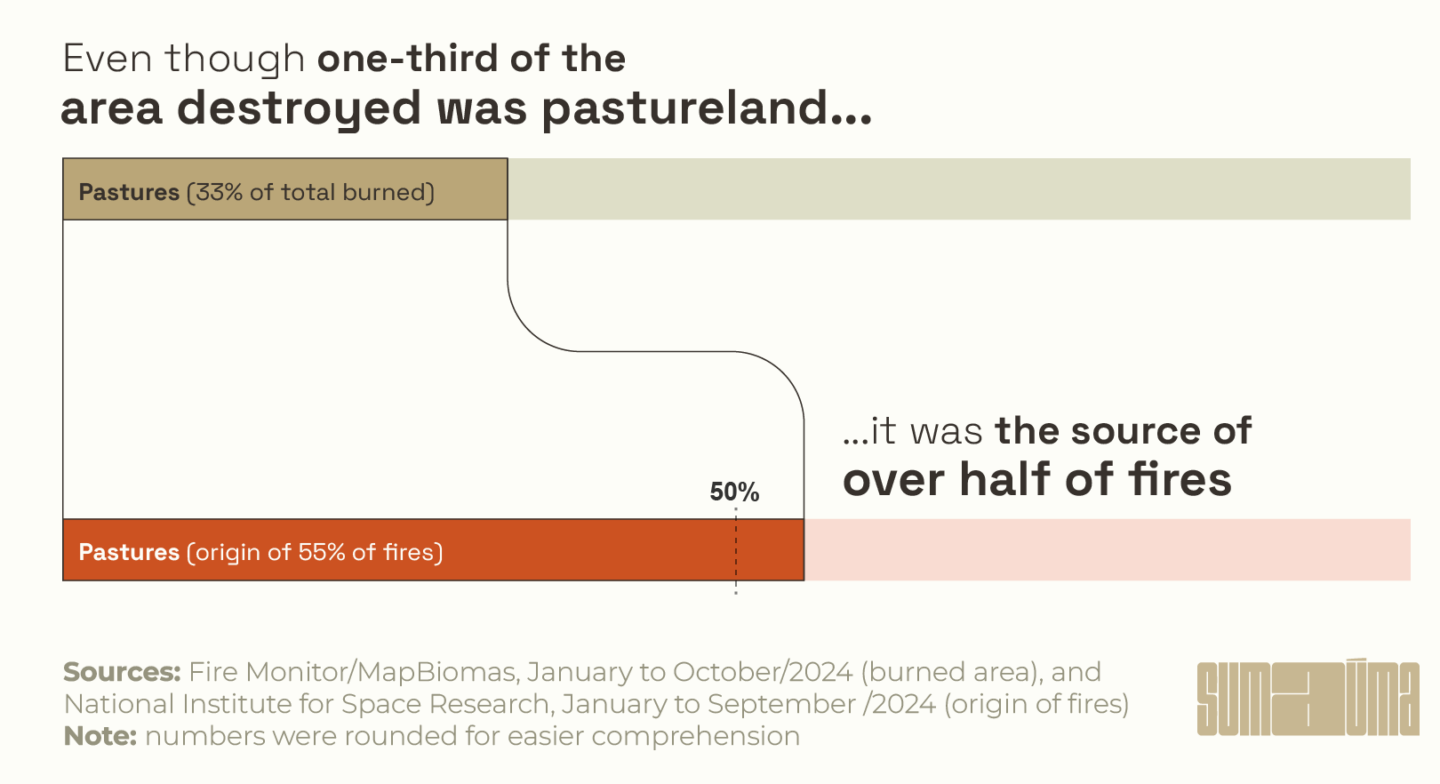

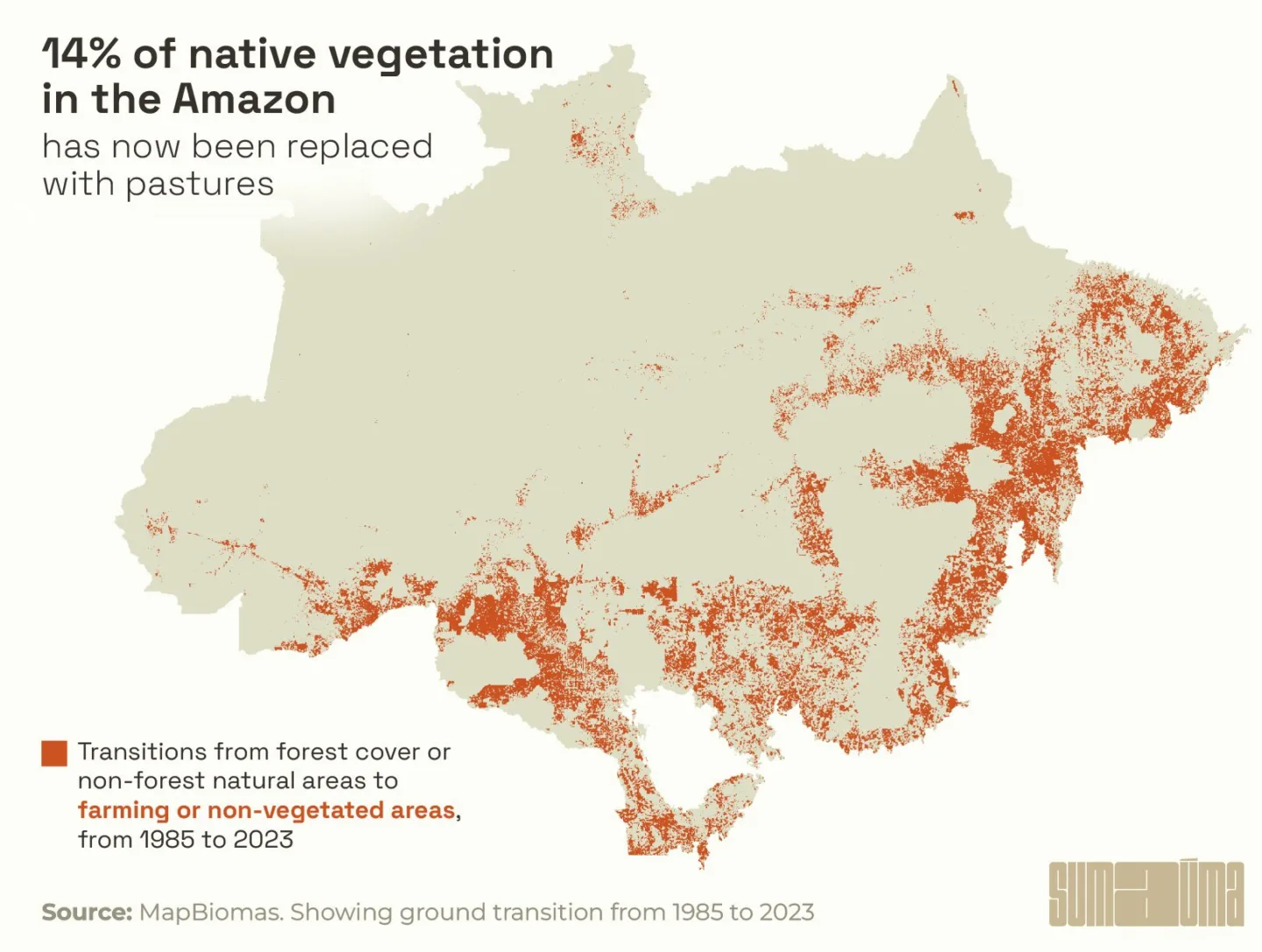

According to the Fire Monitor, most of what burned in the Amazon from January to October 2024 was forest. Yet over half (55%) of fires started in areas where cattle are farmed – the vast majority (86%) of which were cleared after 2015. This means that most of the fires began in regions where there are agricultural activities, but they spread to native vegetation areas. At this point, 14% of the Amazon’s forests have been replaced with pasture.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida/SUMAÚMA

That is why it is no surprise that the few suspects arrested and charged with causing these fires are ranchers and land-grabbers who use fire as a tool to remove native vegetation and clear space for their cattle. That is what investigations by the Federal Police and Civil Police in Mato Grosso and Pará have found.

According to the Federal Police, 112 investigations were opened to look into fires that happened in 2024 in every region of the country (there is no Amazon-specific data). Seven people were arrested and ten were formally charged after sufficient evidence was found to file a criminal complaint. Some of these investigations led to operations like Dracarys, which is targeting those responsible for the deforestation of 1,672 hectares and for setting fire to 2,368 hectares of forest located on public land in the municipalities of Boca do Acre and Pauini, in the southeast of the state of Amazonas – burning an area equal to 15 Ibirapuera Parks, the city of São Paulo’s largest urban green area. According to the Federal Police, “the leader of the criminal scheme” and the “main financial backer and articulator of illegal operations in the two cities in Amazonas resides in an upscale condominium in Campinas [in the interior of the state of São Paulo].” His name was not disclosed.

“In various cases [as with Dracarys] we have signs of planned and coordinated criminal activities, aimed at a subsequent crime, the theft of public lands for livestock farming,” Humberto Freire, a chief of police and the Federal Police’s director of the Amazon and Environment, told SUMAÚMA. Another two police operations in the state targeted public forest arsonists. One of them is looking into fires that ravaged 5,000 hectares of forest to create pastures. Although the crime was committed in Apuí, in southeastern Amazonas, one of the suspects lives in Novo Progresso, in the state of Pará. Two sources in the city told SUMAÚMA the Federal Police were looking at a rancher involved with illegal mining and deforestation in the Jamanxim National Forest, where 17% of the plant cover has already been illegally cleared by land-grabbers in the region.

Distance crime: a public area burned in the Amazon and a mansion in Campinas belonging to the person suspected of ordering the destruction. Photos: Press photos/Federal Police

“The motivation [for the fires] is eminently economic and individual, and the typical criminal is a rancher or logger,” says chief of police Iuri de Castro, a member of the Civil Police of Pará’s Secure Amazon task force. Four people were arrested in the state and eight were charged with arson between 2023 and 2024. Two of those arrested were land-grabbers operating in the Triunfo do Xingu Environmental Protection Area, the most deforested in the Amazon. One of them had deforested and burned 10,000 contiguous hectares of forest. The other suspect had burned 7,000 hectares, despite claiming to “own” an area of “just” 2,000 hectares.

In Mato Grosso, 21 people were arrested during the commission of a crime by the Civil Judicial Police and charges were filed against 149 suspected arsonists between January and September 2024. “Normally it’s the owner [of the land] that does the clearing [of vegetation] and sets a fire to make pastureland. Then the fire comes, and their excuse is that it was somebody else, or it was the wind [that blew in the flames],” explains Liliane Murata, a chief of police whose expertise is the environment. Because each investigation is run by the police station in the region where each fire occurred, and there is no centralized data, she can’t say whether there are any indications of organization among suspects. “We were unable to outline a profile [of the criminals]. If it were centralized at a single precinct, then we could do this,” she argues. Mato Grosso is the third largest state in Brazil in area. Its governor, Mauro Mendes, a member of the União Brasil party, is a staunch defender of agribusiness and has even placed blame – wrongly – on Indigenous peoples for the fires in the state.

SUMAÚMA also asked the police in the states of Acre, Amazonas, Maranhão and Rondônia for information on investigations into forest fires. We received no response. The Civil Police in the state of Tocantins said it had executed “29 procedures related to arson” and made ten arrests during the commission of a crime, but provided no details on the cases.

Crime in command: a brigade of firefighters were driven from Almir Surui’s land. Photo: Ton Molina/AFP and Observa Rondônia

Shots fired at firefighters

The unprecedented drought affecting the Amazon, draining rivers and leaving forest growth much more susceptible to the spread of fire, helps to explain the record number of fires. “This drought, which began in 2023, greatly impacted the forest’s structure. When plants are exposed to moisture stress, they drop their leaves, as part of a protective mechanism to keep them from losing the little water they have. This opens more space for dry wind, radiation, and at the same time increases the amount of combustible material on the ground,” explains geographer Ane Alencar, who researches climate change and forest deforestation and is the science director at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute.

Nevertheless, not even the “extreme climate conditions,” as Ane defines them, provide natural causes for the fire. “It was people who started the fire,” the scientist says. In other words: in 100% of cases, the Amazon was the victim of fires caused by human action.

The case of agronomist Douglas Jobim Vieira is notable. He was caught on September 9 of this year while he was setting fire to a farm in Sorriso, Mato Grosso. Located 420 kilometers to the north of Cuiabá, Sorriso is Brazil’s soybean capital – it was recently named by the Agriculture Ministry as the most prosperous city among Brazilian agribusiness’s 100 wealthiest cities. “Why would an agronomist go around setting fire to properties at the heart of agribusiness in Mato Grosso? Either he’s crazy, or he was fired and they didn’t pay him, or he was given an order,” posits the special secretary of deforestation control and territorial environmental order at the Environment and Climate Change Ministry, André Lima.

He says that some of the fires are suspected to have been set in reaction to renewed initiatives being carried out by organizations like the environmental agency, Ibama, to repress environmental crime. “There are several signs [of this],” he told SUMAÚMA. “We had firefighters being driven out of the area [burning] under gunfire. And explicit announcements [of intent to set fires to exhaust the government], in the case of Jamanxim National Forest,” he adds.

André Lima, of the Environment Ministry: ‘There are several signs’ of fires as retaliation against actions to protect the environment. Photo: Diogo Zacarias/Environment Ministry

An Ibama fire brigade fighting fires in the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Territory, wedged between the states of Mato Grosso and Rondônia, was attacked while combating blazes that started in October. “They started to hear shots being fired. It was a hostile act,” says Jair Schmitt, Ibama’s director of environmental protection. “We had to move back the team, ask for security support, because firefighters can’t be put at risk. It’s not just there. It happens in lots of other Indigenous Territories.” Home to the Surui Paiter people, Sete de Setembro is the target of frequent invasions by land-grabbers and illegal logging operations.

In Novo Progresso, where Jamanxim National Forest is located, a farmer promised to use fire to retaliate against the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation’s seizure of illegal cattle in the region. “I’m going to encourage setting fire to everything,” the land-grabber told the Folha do Progresso newspaper last July. “Here’s the plan. We’re going to move forward with this idea and let the government put it out, let them come and protect their forest.” Novo Progresso was where coordinated forest fires started on Fire Day, in August 2019, when hundreds of fires were set simultaneously by public land thieves, farmers and ranchers, in a “sign of support” for then-president Jair Bolsonaro, of the Liberal Party. The scenario was again repeated right before October 2022, when the far-right president and enemy of environmental conservation was seeking reelection.

“There’s a reaction to the change,” Lima argues. “Environmental policy is operational again. And, obviously, clandestine, criminal activities feed the local economies [in the Amazon] in a way. This starts generating revolt,” he says, before pointing to some data. “[For 2024] we are finding that more than 35% of all burned area sits inside of the [Amazon] forest. Historically, this has never surpassed 15%. This obviously has to do with the drier and more vulnerable forest. But this fire did not necessarily come from the outside in.”

The Surui Paiter’s main leader, Cacique Almir Narayamoga Surui, suspects political motivation is behind the fires in his people’s territory. “It was arson. And they didn’t let [the firefighters] go there. Because [the fire] was supposed to happen,” he says. The fires in the Sete de Setembro Indigenous Territory are now under control. Over 6.9 million hectares were consumed by fire in Indigenous Territories across Brazil like Sete de Setembro between January and October 2024, according to the Fire Monitor. This is growth of over 155% as compared to 2.7 million hectares in the same period in 2023.

Chief of police Humberto Freire is cautious when asked about any political motivation or articulation between the different cases. “It can be found at a later time. That’s why we’ll continue the investigations.” A favorite target of land-grabbers, undesignated public forests – areas belonging to the government, but whose use has yet to be determined – saw the area destroyed by fires nearly triple in 2024. According to a technical note from the Amazon Environmental Research Institute, fire destroyed over 870,000 hectares from January to August, compared to 315,000 for the same period in 2023. This is a 176% spike.

Fire and drought: in Boa Vista, the Branco River dropped so low you can walk along sandbanks that used to be riverbed. Photo: Suamy Beydoun/Folhapress

Impunity reigns

Douglas Jobim Vieira, the agronomist suspected of arson, was released by Mato Grosso’s Civil Judicial Police one day after being arrested. His bail was set at R$ 15,000 by Justice Emanuelle Chiaradia Navarro Mano. Yet he left after paying just R$ 800 to the court – a 95% discount. The Office of the Public Defender of Mato Grosso, which is representing him, claimed Vieira was unable to afford the full bail – and the judge agreed. Days later, on September 17, he was charged by the police. SUMAÚMA requested an interview with the chief of police responsible for the case, but he declined because the investigation had already ended. The case is now with the State Public Prosecutor’s Office. The prosecutor given the case has asked for additional findings in the investigation and also did not want to grant an interview. The Office of the Public Defender, which is representing Vieira, said it will “only speak through court records” on the case, which are under seal. A request to speak with Vieira also went unanswered.

Vieira’s case did not go unnoticed by the Federal Police. “This crime is so serious that it deserved higher bail and not a reduction,” says police chief Humberto Freire. “Unfortunately, we’ve seen that at a broader level, the legislation is quite meek and occurrences are oftentimes dealt with condescendingly.” The 1998 law on environmental crimes establishes a maximum sentence of four years in prison for anyone who “causes a fire in a forest or in other forms of vegetation.” This is less than the six years set forth in the Criminal Code, enacted in 1940, for anyone who “causes fire, putting another’s life, physical integrity or property in danger.”

In an attempt to tackle the problem, the federal government put together a bill to raise the maximum penalty for forest fires to a six-year prison sentence. The bill additionally stipulates that in cases of environmental crimes with participation by criminal organizations, “special techniques” can be used in investigations, such as undercover agents and plea bargains.

“Penalties are [currently] very low. All of the agencies working to combat environmental crimes are unanimous on this point,” agrees the secretary of legislative affairs at the Justice and Public Security Ministry, Marivaldo Pereira. “No matter how serious the crime is, it hardly results in prison time. It’s absolutely disproportional in relation to other crimes. For example: setting up an illegal mining operation, with barges, destroying the river, has a lesser penalty than larceny, which is a non-violent crime with no serious threat.”

Legislative foot dragging

The bill with these changes is in Congress now, but a rapporteur has yet to be determined. Instead, Marivaldo Pereira is negotiating with lower house members who report on similar matters, so they can pick up the suggestions proposed by the government in the final report. For any bill to pass, it needs to be put to a vote in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate. It would only impact crimes committed after the new law takes effect.

Even if a stricter law took effect, it would still be hard to catch and arrest arsonists. “It’s a sneaky crime,” says André Lima, of the Environment and Climate Change Ministry. Deforestation done using chainsaws and tractors is noisy, it demands weeks of work, and it is detected by radars and combated in a timely manner by environmental enforcement. While setting fire, during a drought like in 2024, requires no more than a box of matches.

A common view in the government is that fire is used as a tool of deforestation by public land thieves. “With the low humidity and the prolonged drought favoring the fire’s spread, why [would the criminal] use heavy equipment [in deforestation], which is easier to identify?” asks Humberto Freire. “There may be a change happening in the criminal strategy to devastate native vegetation to steal public lands later. This has been recurrent in investigations.”

This argument makes sense, says Ane Alencar, of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute. “The people who want to occupy public lands know the government is more present, making their action riskier. A land-grabber won’t invest in a chainsaw, in hiring people, because they know the Federal Police or [environmental agency] Ibama could come knocking. With the climate leaving the forest highly flammable, it’s much easier to just start a fire.”

Lima compares this with cell phone theft in large cities. “You don’t catch the thief in the act, in São Paulo, stealing a cell phone. The guy walks by, breaks the [car] window, and leaves. This is in a metropolis, with hundreds of witnesses. Imagine [setting fire to the Amazon forest] without any witnesses. Maybe you’ll recover the cell phone, through tracking, find the person who received it [the stolen object’s buyer]. But you don’t catch the thief. And the fire? Who is receiving the fire? The ‘victim,’” he says. Put another way, the person setting the fire can claim to be its victim to the authorities, since it is virtually impossible, in remote regions of the Amazon, to identify who started the fire.

This view is shared by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Federal Police. “The existence of the crime, the fire, is evident. But the perpetrator is almost always very hard to establish. And it isn’t resolved overnight. It requires investigation, which is something slow,” says prosecutor Luiza Frischeisen, the coordinator of the 4th Chamber of Coordination and Review at the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, which is responsible for crimes against the environment. “It is a very large number of cases. We don’t have any way to investigate each outbreak of fire,” says chief of police Humberto Freire.

This opens a window of opportunities for criminals, who know they are at even less risk of being caught. “With so many cases, the strength is drained from the government’s response. And then there may be people who take advantage of the moment to clear an area, using fire, who had never done it before, out of fear,” the police chief explains. An agent experienced with fighting environmental crimes sees another possibility, referred to in criminal jargon as a copycat crime. “It’s normal for crimes with repercussion and visibility to be replicated elsewhere, whether because of notoriety or ideological motivation. January 8 [in Brasília, when Jair Bolsonaro’s voters vandalized the Praça dos Três Poderes because they were frustrated with the lack of a coup against Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva taking office] is a typical example, inspired by the invasion at the US capitol,” says this source.

Or rather, those who wanted to see the Lula administration in a tight spot because of the forest fires could also be driven to strike a match and toss it into a dry thicket somewhere. And there is no reason, so far, to believe it will be different in 2025.

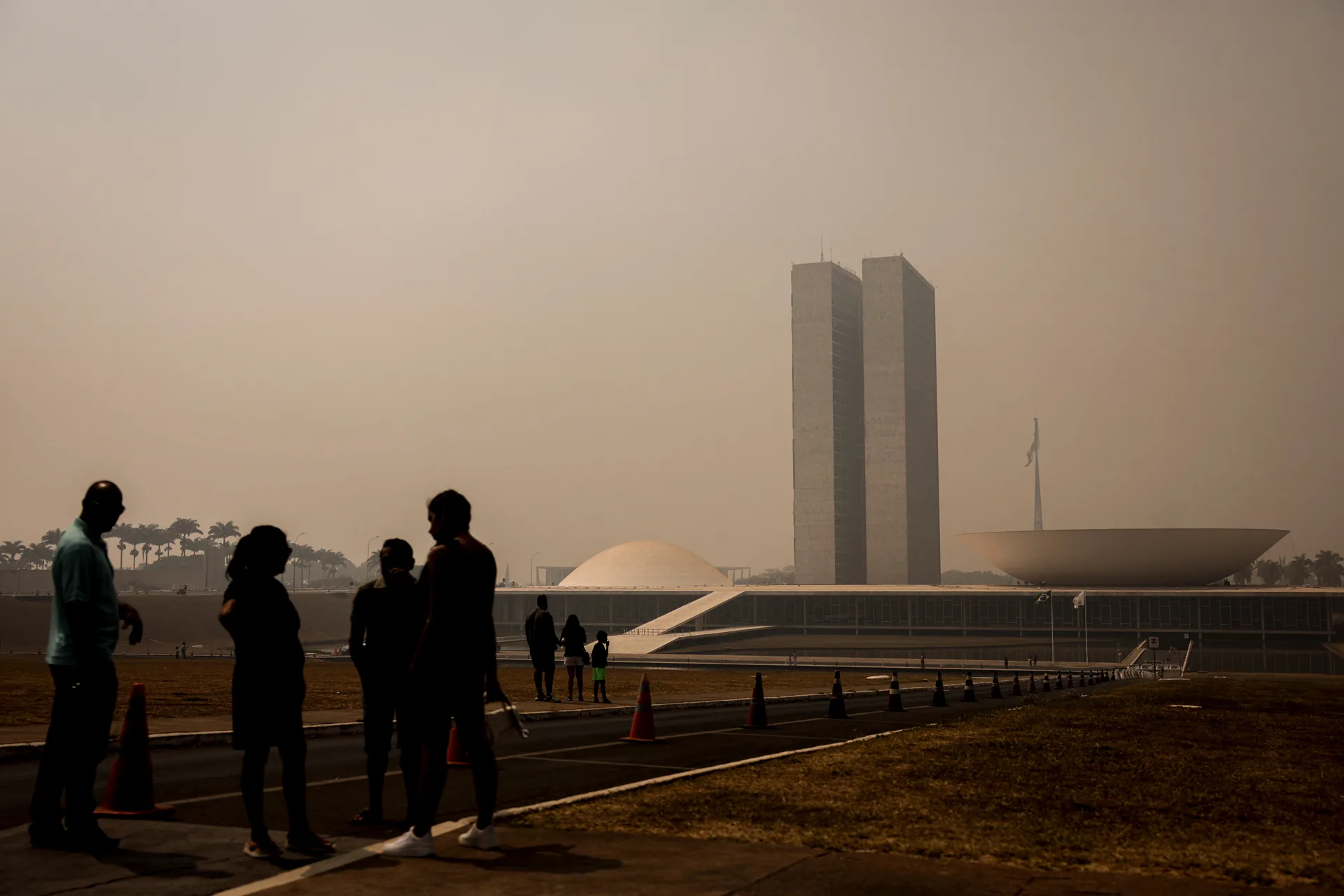

In Brasília, just like the Amazon: smoke from forest fires also blanketed the nation’s capital in August and September 2024. Photo: Marcelo Camargo/Agência Brasil

‘Running from one fire to another’

“Forest fires are now one of our biggest challenges to achieving zero deforestation [in the Amazon],” says André Lima. He is referring to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s promise to create conditions and policies that will lead to zero deforestation in the biome by 2030.

In this scenario, fighting the fires is as important as finding those responsible. The Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation, responsible for conservation units like parks and national forests, has a total of 95 fire brigades, made up of 1,270 people, at press time. Environmental agency Ibama, which works within undesignated public forests and Indigenous Territories, has 65 fire brigades made up of 1,445 agents in Amazonian states. It is little manpower for a scenario like 2024.

“The big challenge is stopping ignitions [of new fires]. We’re doing the fighting, but 50 large new fires emerge each week in the Cerrado,” says Lima. “And we don’t have 50 new teams to send to these new fires, because they’re already putting out current fires. The guy would need two days to rest before going to the next one, but there are folks who’ve gone three months practically sleeping in the truck between one fire and another.”

This is why he believes that firefighting needs to be planned “from the bottom up,” building what are called fire-resilient communities. “If each rural property had two fire extinguishers, we would have 200 people to put out fires in a 50-kilometer radius, connected by WhatsApp. Today we don’t have a fire brigade with 200 people anywhere in Brazil,” he argues. Rural property owners need to join the effort. “That club that caught fire in Rio Grande do Sul [the Kiss nightclub, in Santa Maria, causing the deaths of 242 people in 2013] had to have a range of measures against fire. But it didn’t have them, and had to be punished for this. In a hotel, restaurant, shopping center, any economic endeavor where there is a risk of fire, the developer is required to take preventive measures. Why isn’t it so on rural properties?” he asks.

Fires on large rural properties nearly tripled from January to August 2024, according to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute. Over 2.8 million hectares burned on large landholdings, compared to a little over 1 million in the last year. Nevertheless, the powerful ruralist lobby reacted and is promising to overturn a federal government decree punishing farmers for failing to act against fire. If they sustain their position on the bill to harden penalties, the Agriculture Parliamentary Front will be contributing to a repeat of the frightening fires of 2024 in the Amazonian summers to come.

Uneven fight: firefighters put out flames in Guajará-Mirim, Rondônia, in August 2024. Photo: Mayangdi Inzaulgarat/Ibama

Report and text: Rafael Moro Martins

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Art editor: Cacao Sousa

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia and Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum