Ecuadorians will go to the polls on August 20 to elect a president, a vice president, and members of congress. Early elections were called in May after Guillermo Lasso, the current president, dissolved the National Assembly while facing impeachment. On this same day, electors will also vote on an unprecedented referendum, to decide whether to stop oil exploration in an environmentally sensitive zone of the Amazon.

The referendum will end a civil society court claim that has been ongoing for ten years now at Yasuní National Park, a jewel of Amazonian biodiversity that is occupied by Indigenous peoples. The case of the park is just one example of how countries in Latin America are still resistant to giving up fossil fuels. One argument that comes up over and over is that exploration is important to economies and energy independence. It’s just that nobody let the planet know about this.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the world cannot afford to authorize any new fossil fuel projects if there is to be a chance of keeping global warming to 1.5ºC, as set forth in the Paris Agreement. From the USA. to the Arab world, from Norway to Russia, every major oil and gas producer is solemnly ignoring the agency and ramping up production. Most of Latin America is following suit.

According to a report by the Energy Information System of Latin America and the Caribbean (sieLAC), the region holds the world’s second largest oil reserve (19.5%), trailing only the Middle East (47.8%). Brazil, Argentina, and Guyana are indicated as the countries leading production in the region. The World Energy 2023 report found that crude oil production in Brazil grew by 3.9% from 2012 to 2022, for example. Argentina had a 0.6% rate of growth in that same period. While Guyana has just recently discovered oil reserves.

Blackmail

Ecuador has been exploring fossil fuels for fifty-one years, with most reserves located in the Amazon. The Yasuní National Park, covering an area of around 3,800 square miles, lies in this region and is home to thousands of species of trees and animals.

In 2000, environmentalists reported that oil companies were causing environmental damage to the park. Years later, social organizations expressed their concern about Brazil’s Petrobras being granted a license to explore a block in the park – this authorization was later suspended by Ecuador. In 2019, the Waorani people successfully lobbied the courts to block exploration in one of the oil blocks.

In 2007, then-President Rafael Correa introduced a plan to stop oil extraction from starting up in Yasuní fields. This initiative consisted of the creation of a US$ 3.6 billion fund with the help of wealthy countries to compensate the country for lost exploration opportunities. At COP13, the climate conference held in Bali that same year, this move was seen as blackmail by Ecuador and the amount stipulated was not raised. In 2013, Correa ended the program, arguing that the world had failed the country.

The president’s next move was to get Ecuador’s National Congress to authorize exploration of the area. “The Constitution [of Ecuador] prohibits exploration in national parks, unless it is declared as being in the public interest. That is why it has to go through Parliament and Correa has a majority in Parliament,” explained Juan Crespo, a research coordinator with the Cuencas Sagradas Amazónicas alliance of Indigenous organizations.

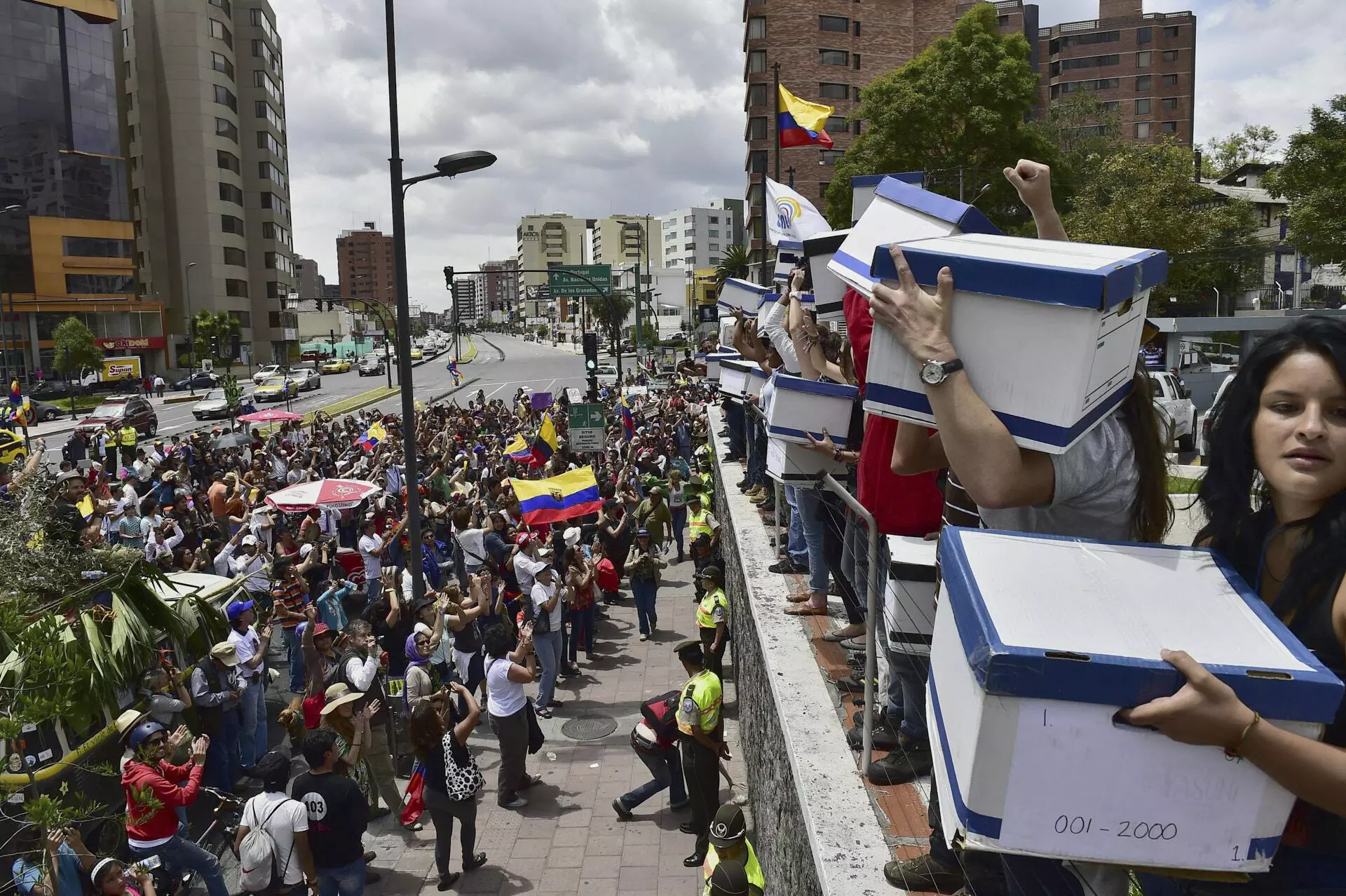

Waorani people and members of the Yasunidos group at a protest in Quito against oil exploration in Yasuní National Park. Photo: Rodrigo Buendia/AFP

In light of this about-face, the Yasunidos collective emerged, starting a campaign in 2013 to gather enough signatures for a popular consultation to decide whether one of the park’s blocks should be explored. Following a series of problems, including the National Electoral Council’s rejection of signatures, the dispute landed in Ecuador’s Constitutional Court. It was only in May of this year that the right to hold the referendum was upheld. Amidst this conflict, oil extraction began in 2016 in the Tiputini field, also known as Block 43.

A majority vote of “yes” to end exploration would mean that state-owned Petroecuador will have one year to leave the block – the country’s fourth largest oil block, responsible for 15% of total national oil production. If the public halts production there, Ecuador will still continue to extract oil from other blocks. Even so, Crespo believes that suspending exploration will be a huge win. “The fact that there is a country, no matter how small, that can do this through a democratic process, which is very symbolic to me, I think that it could somehow encourage replication in other countries,” he says.

Ilan Zugman, Latin America managing director for 350.org, underscores the strength of the popular movement in getting the referendum on the ballot, but stresses that a more robust shift on fossil fuels will depend on who wins the presidential election in Ecuador.

The Brazilian Amazon at risk

The saga of the Amazon is not restricted to Ecuador. In Brazil, Rio de Janeiro-based Eneva, a private natural gas operator, opened its Azulão Gas Treatment Unit in September 2021, located between Silves and Itapiranga, in the state of Amazonas. This area is near the Mura peoples’ territory. Their leader, Jonas Mura, told the InfoAmazonia website that game animals and fish began to leave after the company started its operations.

The Environmental Protection Institute of Amazonas (Ipaam), a state government agency, approved Eneva’s construction license in 2019. Its operating license was granted in 2021. Nevertheless, the Environmental Impact Study, an essential document in the licensing process, dates to 2013 and was drafted by Petrobras, the field’s former owner. In May, the federal courts in the state of Amazonas suspended these licenses based on reports of problems in the licensing process and insufficient consultation with Indigenous peoples. A few days later, the company was able to lift a preliminary injunction to resume exploration.

Far away, but still in the Amazon, the trouble is with Petrobras. In May, Brazil’s environmental agency Ibama denied the company an environmental license to look for oil in the Foz do Amazonas basin, off the coast of the state of Amapá. The technical report that served as the basis for the agency’s decision indicated the study submitted by Petrobras did not cover all of the undertaking’s environmental impacts, it did not include adequate mitigation of any impacts on marine life from oil leaks, and it did not establish coastal monitoring actions. Brazil’s Equatorial Margin, as the oil frontier that goes from Amapá to Rio Grande do Norte is called, has stoked Brazil’s ambitions to place the country in a higher position among the world’s largest producers of fossil fuels – the head of the Ministry of Mines and Energy, Alexandre Silveira (Social Democratic Party for the state of Minas Gerais), wants to see the country shoot up from the ninth to the fourth largest producer. According to its 2023-2027 Strategic Plan, Petrobras is planning to spend US$ 64 billion on exploration and production, with US$ 3 billion allocated to the Equatorial Margin. Silveira says the region could be the next pre-salt oil region and that it doesn’t make any sense for Guyana to attract investments and wealth while Brazil stands still.

The Mines and Energy Minister’s mention of Guyana refers to reserves containing 11 billion barrels that were discovered there by the US-based ExxonMobil in 2015, which could make the country one of the world’s biggest oil producers. Exxon is still the only company carrying out exploration, but in June Canada’s CGX Energy announced it had found more oil in deep waters off the Guyanan coast. Guyana will also auction off exploratory blocks, which should raise the number of companies in the region. Petrobras is not ruling out the possibility of taking part in the auction if it is unable to obtain licensing to explore Block 59 in Brazil’s Equatorial Margin.

With an eye on its neighbors, Petrobras said it is looking at resuming investments in Venezuela, which holds one of Latin America’s largest oil and gas reserves. The Brazilian state-owned company also intends to renew investments in Bolivia to obtain natural gas, with production having fallen so much that in 2015 then-President Evo Morales issued a decree to open up gas exploration in environmentally-protected areas. In April, under the leadership of President Luís Arce, Bolivia announced an investment plan to carry out eighteen fossil fuel exploration projects, which includes oil in areas located in the Amazon.

“Bolivia has decided to expand its oil frontier and make environmental and social norms flexible. Additionally, it has included the Amazon as an exploration zone,” laments Jorge Campanini, a researcher with the Documentation and Information Center of Bolivia (CEDIB), who points out that the country has no effective energy transition projects. Campanini notes that Bolivia should lose more market share as a result of the vast reserves in Vaca Muerta, in neighboring Argentina.

Fracturing Patagonia

Argentina: an area with toxic waste from fracking, a technique where chemicals are injected into the ground to remove fuel. Photo: Greenpeace

Vaca Muerta is a geological formation occupying areas in the provinces of La Pampa, Mendonza, Rio Negro, and Neuquén, in Patagonia. According to Argentina’s government, it is the world’s second largest gas reserve and the fourth largest reserve of unconventional oil, which gets its name because it is contained in small pores within rock, instead of being in a reserve, which prevents extraction by drilling. The government says that the fossil gas in this region will guarantee abundant and clean energy for Argentinians, while also affirming that it is changing the energy situation in the country.

Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is needed to explore the Vaca Muerta reserves. This consists of a technique where large amounts of water, sand, and chemicals are injected into the ground to break apart rock, allowing fuel to reach the surface. “Fracking requires more energy than conventional extraction methods,” explains Juan Antonio Acacio, a researcher with the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Institute at National University of La Plata (UNLP).

Acacio says that the Argentine government’s biggest efforts have gone toward promoting the idea that natural gas is important to the transition. The “National Energy Plan for 2030,” published by the government in May, reinforces natural gas use as an energy source. Decrees issued in 2020 and 2022 have also been favorable to this fuel.

Peru is using the same argument to finalize work on its Integrated Gas Transport System. However, a 2021 report from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) points to holes in the idea that natural gas could be a bridge to transition, because burning natural gas emits less carbon gas than coal. The report says that growth in the gas supply could delay decarbonization, since the amount of methane leaked during gas production is usually underestimated. Although there is a small amount in the atmosphere compared to CO2, methane is twenty-eight times more powerful when it comes to holding in heat.

In July, Argentina opened the first stretch of a pipeline to move gas produced in Vaca Muerta. Brazil may help to finance the second stretch. “Rather than thinking about a gas pipeline, it would be good to think about regional policies for energy transition,” Acacio says. Another country interested in backing the project financially is China.

‘Self-sufficiency’

Mexico is another country working to maintain the fossil fuel industry. “There is no medium- and long-term plan to reduce and remove fuels from the economy. The government’s priority has been to reduce fossil fuel imports,” says José Maria Valenzuela, a Mexican researcher at the Institute for Science, Innovation and Society at the University of Oxford, in England.

In a March interview, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador raved about “rescuing the oil industry” to build a path to energy self-sufficiency. Mexico is the number two oil producer in Latin America, yet it imports nearly 80% of its fuel. López Obrador’s management plan aims to boost production, turning it into gas and diesel within the country itself by 2024. To accomplish this project, the government has overhauled six refineries, it has purchased Deer Park in the United States, and it has built a refinery in Dos Bocas, in the state of Tabasco.

Oil drilling in deep waters in Mexico, sixty miles off the coast of the state of Veracruz. Photo: Prometeo Lucero/Greenpeace

According to Sandra Letícia Guzmán Luna, the founder and director of the Climate Finance Group of Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC), the country could invest in an energy transition, but it prefers to maintain a polluting resource. “There is a chance for investment, but this will only happen when we have a long-term view and we understand the complexity of the climate crisis, which this government simply does not understand,” she says.

The company leading the government’s projects is state-owned Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), an accident-prone institution. The latest tragedy occurred on July 7, when a natural gas platform exploded in Campeche, with over 300 workers on it. At least two died and five were injured.

Despite government investment in Pemex’s domination of the fossil fuel industry, international oil companies continue to hold contracts in the country. Italy’s Eni, for instance, has been in Mexico since 2006 and in March it announced the discovery of a new reserve in deep waters in the Sureste Basin, holding an estimated 200 million barrels of oil.

While Canada’s TC Energy is planning to build a new 770-kilometer long gas pipeline that will go from Texas, in the U.S.A., to Veracruz, Mexico, with the promise of increasing natural gas imports by 40%. The country is the top importer of natural gas from the United States.

Mexico is also betting on coal, the most polluting of all fossil fuels. Although it is not Latin America’s biggest coal producer, Mexico was the biggest emitter of CO2 last year because of its coal use, according to the World Energy 2023 report. In 2020, Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission (CFE) announced it would purchase two million metric tons of coal by the end of 2021, mostly from micro and small producers. In 2022, the CFE said coal acquisitions had been successful and it would expand the program by 2024.

While the CFE is singing the praises of the program, it doesn’t talk about its problems. In August of last year, ten workers died when they were trapped in a mine located in Sabinas, in the state of Coahuila. They were working on a nearly 200-foot-deep well when a jet of groundwater softened the walls. Another five were rescued and survived.

Family members of the ten workers who died after being trapped in a mine located in Sabinas, Mexico. Photo: Pedro Pardo/AFP

Mexico is responsible for 1.35% of all emissions, making it the 14th biggest emitter in the world. However, this does not exempt the country from changing its energy mix. Valenzuela feels Mexico needs to have an effective policy to keep the fossil fuel industry from expanding and coal could be the first thing to go, since it accounts for less than 10% of the country’s energy mix. “Prioritizing investments in other sectors starts making it so that this will grow smaller.”

The wrong way for Petro

When Gustavo Petro was sworn in as Colombia’s president in August 2022, it was with an environmental discourse. In February, the president introduced his National Development Plan, which highlighted the environment and contained a proposal not to allow new concessions for large-scale and open-pit mining of coal.

However, environmentalists thought the measure was weak, since it would keep concessions that were already in effect. Although watered down, it was defeated in congress. Despite criticism, the plan contains articles on developing the bioeconomy, on diversified production in mining districts, and on investments in green hydrogen, in addition to other actions to lower pollutant gas emissions.

Colombia’s president was also able to pass an anti-fracking bill in the Senate, but it is facing opposition from senators. Ecopetrol, a Colombian company whose biggest shareholder is the Colombian government, stopped fracking last September because of the discussion on the bill. The company also does not use fracking to extract fuel in operations outside of the country.

Coal mine in Colombia; the country is one of the few on the subcontinent whose president, Gustavo Petro, has an environmentalist discourse and advocates for an energy transition. Photo: Tenenhaus

Petro continues to be critical of coal and in a June speech he noted that the growth of this fossil fuel makes neither economic nor environmental sense. Álvaro Pardo, the president of the National Mining Agency, had already reiterated that Colombia wants to overcome an economic dependence on fossil fuels and make a socially just energy transition, calling on international cooperation for help.

Early in the year, Petro challenged wealthy countries by proposing that external debt be written off in exchange for effective environmental services to deal with the climate emergency, and in June he suggested an international financial fund be created to fight climate change. Colombia is also planning to join an alliance where countries make donations or provide loans for other countries to make progress in their energy transitions.

“There are still not many concrete things, but we’re seeing the effort [by Colombia]. It is going beyond discourse. There are things happening, but in the country’s own time,” says Ilan Zugman, pointing out that Colombia faces a huge challenge, since the country’s economy is still highly dependent on fossil fuels. Finally, Petro asked President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to think about the exploration of fossil fuels in the Amazon at a meeting earlier this month in Letícia, Colombia, a city that lies on the border with Brazil “Are we going to allow hydrocarbon exploration in the Amazon jungle?” he asked. Lula deflected the question.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photography editing: Mariana Greif

Page setup: Érica Saboya

Lula and Petro in Leticia, Colombia. Photo: Andrea Puentes/Office of the President of Colombia