The banging of a hammer announces the building of a small wooden structure just over 10 feet square. It is being put together by Quilombolas—descendants of rebel slaves—in the community of São Rosário in the Brazilian Amazon state of Pará. In just a few hours, the structure will support a long-awaited Starlink antenna. José Carlos Galiza, of the National Coordinating Board for the Alliance of Rural Black Quilombola Communities (Conaq), receives a warm welcome from local traditional communities when he arrives with the antenna, which will link to one of multibillionaire Elon Musk’s SpaceX satellites. For people living in areas of dense forest and plentiful rivers and streams, strengthening connections to other communities and the state capital can mean “the difference between life and death,” in Galiza’s words. “Many of these places are medical deserts. There are no doctors, nurses, or even community health agents,” the Conaq leader told SUMAÚMA. Galiza works with Forest Peoples Connection, a civil society project focused on taking the internet deep into the Amazon.

Just as the internet may have the potential to improve healthcare access, the same may be true in education. Nazilene Andrade, 24, a single mother of three, believes internet access may change her and her children’s living situation. Nazilene received a full scholarship for a nursing course that requires attendance both in person and online, but her lack of internet access forced her to drop out. Then she discovered she had three months to resume her studies. “With the internet coming to our community,” she says, “I’ll be able to go back to studying.”

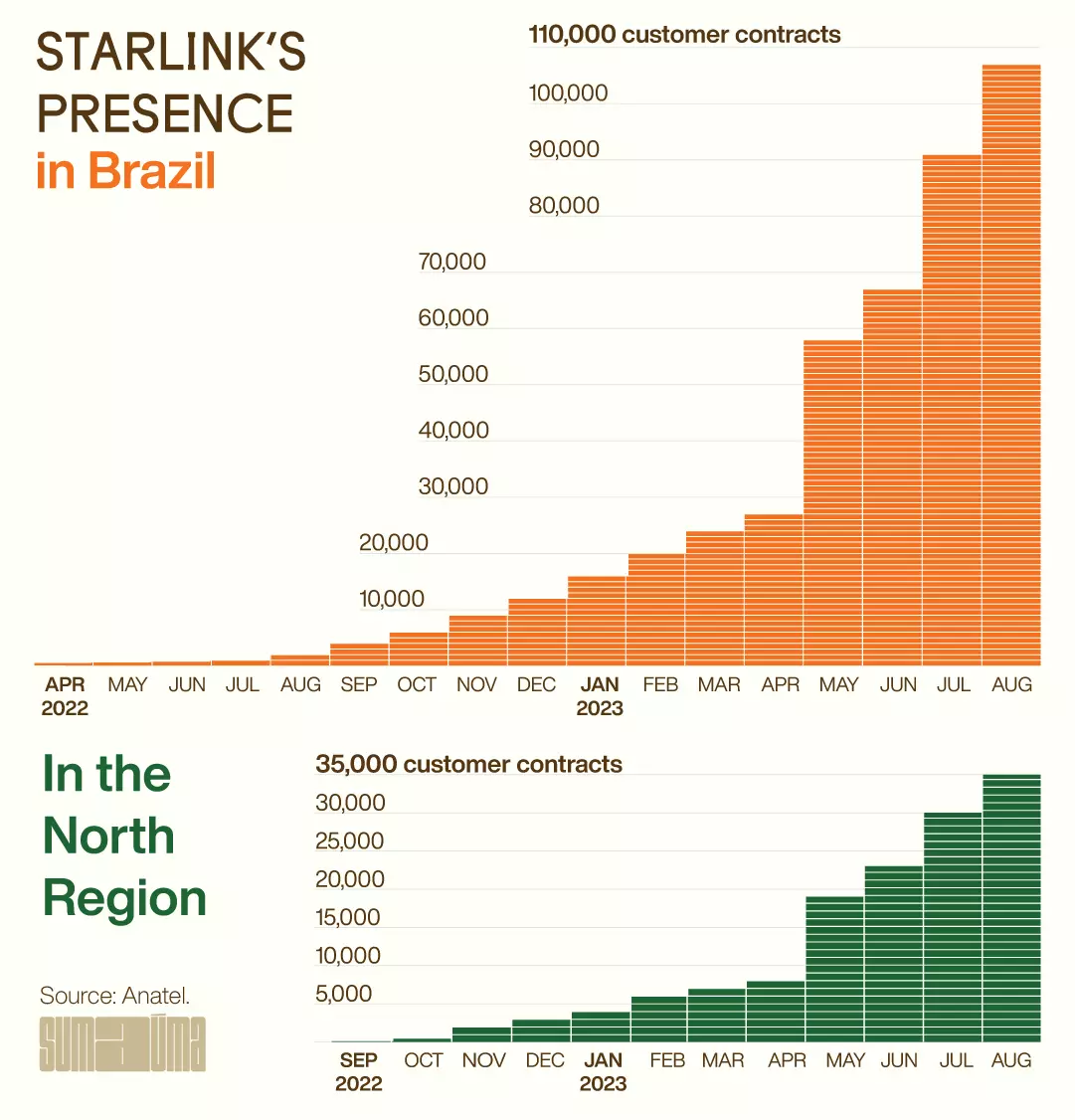

Before Starlink, internet services were rare in more distant corners of the rainforest. This scenario has changed rapidly since September 2022, when the company owned by Elon Musk, presently the wealthiest man in the world, began operating in what is known as the Legal Amazon (comprising the states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, Tocantins, and part of Maranhão). This new technology affords a stable internet connection in remote, hard-to-reach areas.

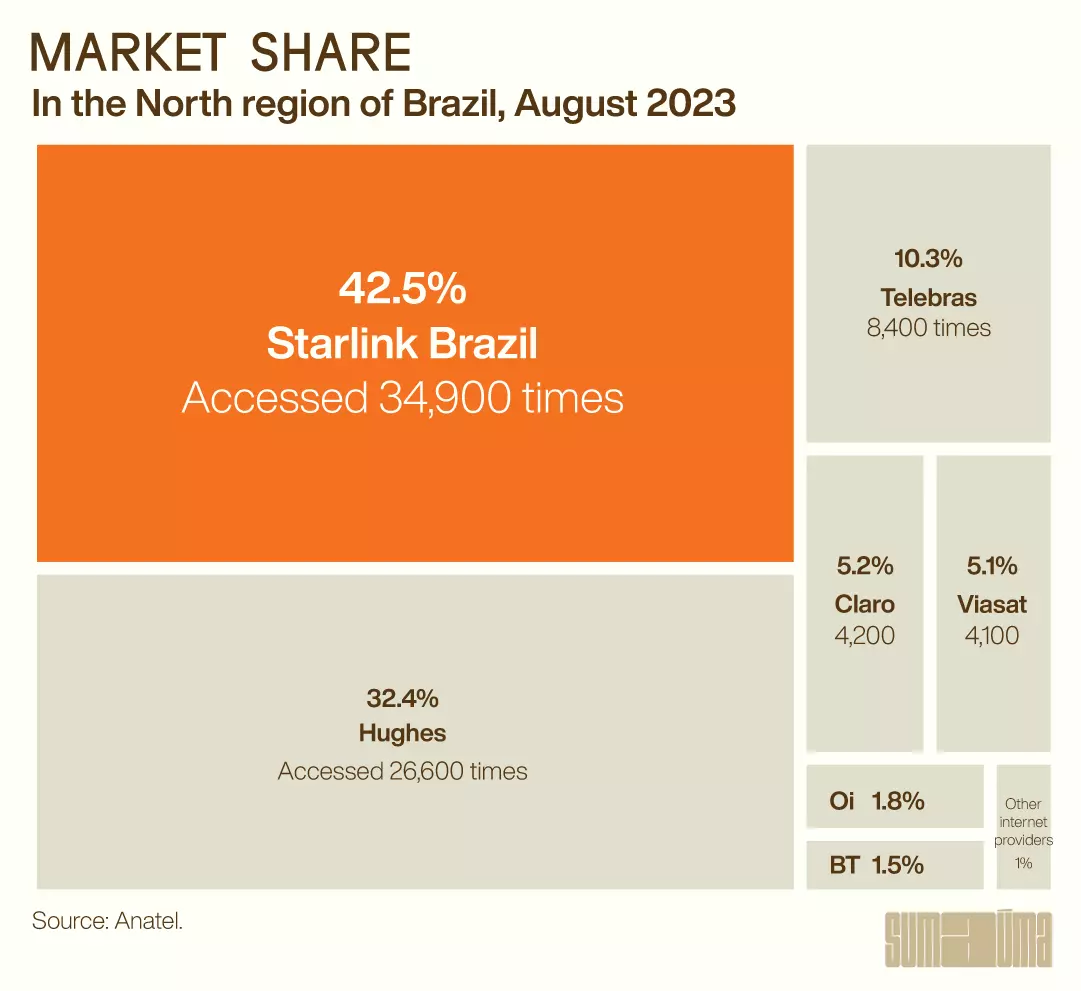

By the close of the first half of this year, according to data from Brazil’s National Telecommunications Agency, or Anatel, Starlink had become the most widely used satellite internet provider in the North. In August, the company held a 42.5% share of the region’s satellite market and 35,000 contracts. A survey carried out by BBC News based on Anatel data showed that Musk’s company now has private customers in 697 of the 772 municipalities in the Legal Amazon, which is 90% of the total.

Musk’s system has drawn the interest of Indigenous peoples, traditional communities, Quilombolas, Ribeirinhos (residents of traditional riverside communities), public agents working in oversight, education, and health, and activists in the Amazon region. For all of these people, the internet is a tool that can create opportunities in telemedicine, distance education, politics, business, leisure, and the fight against human rights abuses, legal violations and the destruction of nature.

The São Rosário quilombola community, in Pará state, was excited to get the antennas. Residents say the internet is essential for access to education and health. Photo: Filipe Bispo/SUMAÚMA

One of Galiza’s concerns is the lack of digital literacy in these communities. He has urged Quilombo residents to consume only trustworthy content on the web and to utilize the internet as a tool to monitor what is happening in the territory and also to combat land grabbing, deforestation, and burn-offs. His warnings make sense, particularly because a Starlink antenna is part of the basic toolkit of forest destroyers.

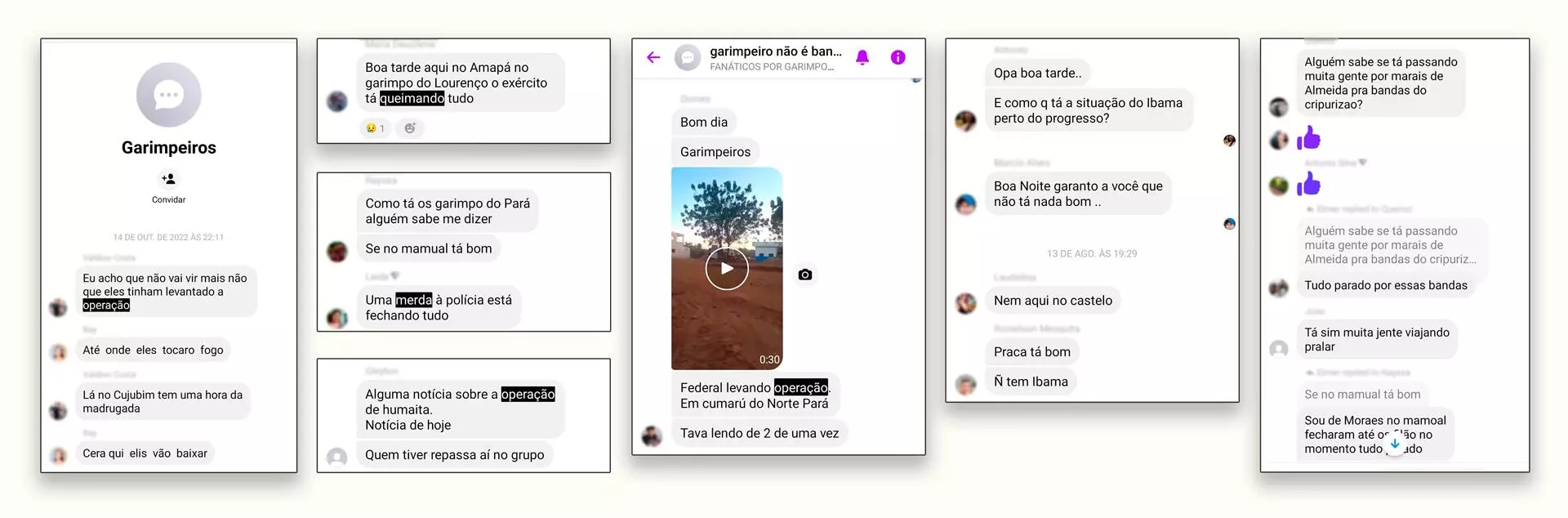

On the radar at the Federal Police and Brazil’s environmental protection agency Ibama, there is now ample proof that illegal miners have been quick to take advantage of the connected world offered by Starlink, relying on it in their criminal operations. They exchange advance information on probable operations against their criminal mining activities, do business while illegally extracting gold from protected areas, or simply post TikTok videos and talk with their families. They are joined by loggers, landgrabbers, and drug traffickers, along with large landowners and transnational mining companies. “Starlink wants to sell its product. Just like it sells to us Quilombolas and forest peoples, it sells to anybody. And there’s nothing we can do about it,” says Galiza.

Since the Jair Bolsonaro administration (2019-2022) authorized Musk’s company to begin operating in the country, the Brazilian State has failed to conduct a single study on the impact of Starlink’s presence in the Amazon, nor has it fostered a public discussion centered on the possible need for further regulations. Musk’s alignment with the global far right is apparent. In May 2022, Bolsonaro met with Musk in Porto Feliz, a town in rural São Paulo, where the billionaire was awarded a medal of honor. After a closed-door meeting, Bolsonaro called Musk “a hero of freedom” for having purchased Twitter.

Elon Musk’s alignment with the global far right is notorious. In Brazil, the multi-billionaire was received by Bolsonaro in Porto Feliz, in rural São Paulo state, where he was awarded a medal. Photo: Clauber Cleber Caetano/PR

Starlink has spread so fast there is a real risk it will become a monopoly, according to experts heard by SUMAÚMA. The company is owned by an erratic, untrustworthy foreign billionaire with clear political interests. Ultimately, a single player has concentrated a collection of sensitive data in his hands, such as information on geolocation and usage frequency—and precisely in a strategic region of the world. Finally, introducing the internet to traditional communities may lead to profound cultural changes, something public authorities should monitor.

Internet used to be expensive, rare, and bad

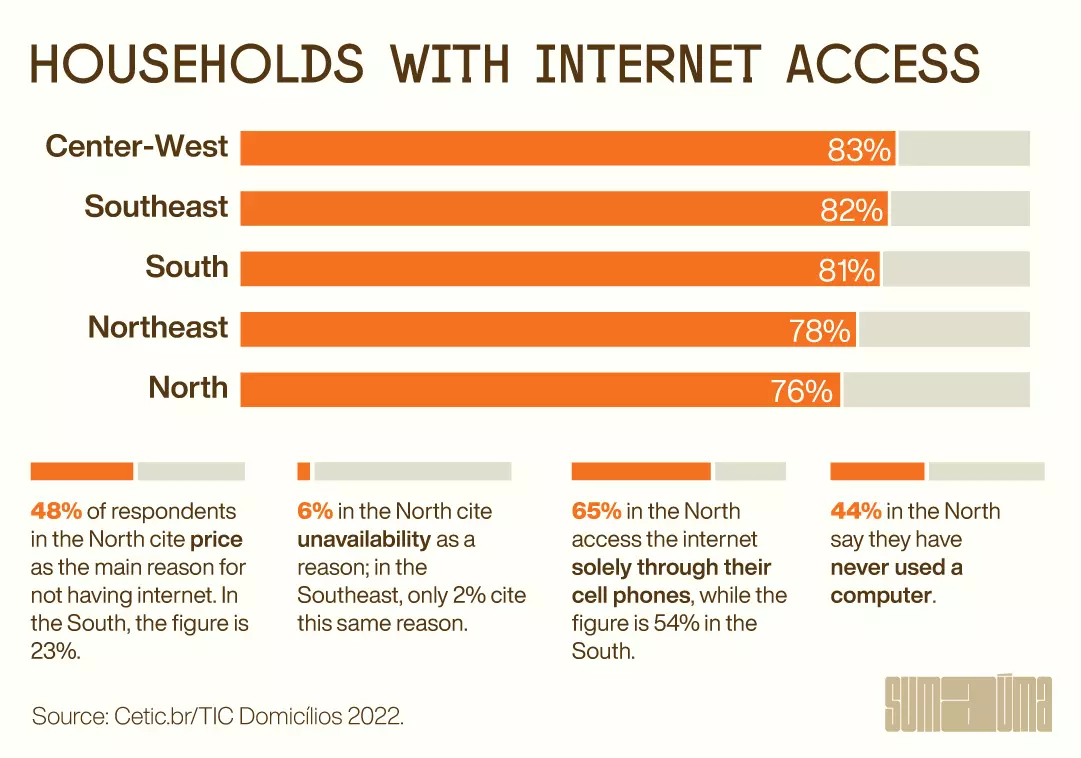

The North displays Brazil’s worst internet usage indicators, according to the Household ICT Survey for 2022, conducted by the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee, a multisector agency responsible for defining strategic guidelines on internet use and development in Brazil. Another study, by the Brazilian Consumer Defense Institute, has underscored that “poor connection quality, limited coverage, and exorbitant prices are the chief characteristics of internet access in the North.” Outside the region’s largest cities, internet access is generally expensive and poor.

“In Manaus, you pay 99 reals [roughly $20] for a speed of 350 Mbps. But in Coari [about 215 miles to the west], 10 Mbps costs 300 reais,” says Hemanuel Veras, who is doing his doctoral research on connectivity in the Amazon at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro’s School of Communication and is a member of the Public Center for Communication and Audiovisual in Manaus, capital of Amazonas state.

Before Starlink arrived, two federal programs were working to mitigate connectivity issues by installing Optical Transport Networks (OTN) along rivers in the Amazon. In 2014, the National Research Network and the Brazilian Army signed an agreement to undertake the Connected Amazon Project to serve residents in riverside towns. In 2016, this initiative brought fiber optic internet to Manaus; this was followed by a 136-mile stretch between the towns of Coari and Tefé, both in Amazonas. The project has been used primarily by the Army.

The other project, called the Connected North Program, announced in September 2021 under Bolsonaro’s administration, was meant to expand communications infrastructure in the Amazon region through fiber optic networks. Maintained by the Lula administration with no visible changes, Connected North will build eight OTNs along rivers with the goal of connecting public spaces like schools, universities, hospitals, and courtrooms. Total coverage is forecast at over 4,600 square miles with some ten million people served in 59 municipalities, at a cost of roughly $267 million, sourced from the 5G auction.

The Lula administration has continued the Connected North Program, devised by Bolsonaro. The president was in Santarém, Pará, in August to inaugurate an Optical Transport Network. Photo: Marco Santos/Agência Pará

“So far, these programs haven’t been very transparent about how this will reach the end user, the general public,” says researcher Hemanuel Veras.

The arrival of Starlink

The Bolsonaro administration demonstrated a clear interest in Starlink, claiming it would be impossible to connect the Amazon without satellites. The government then talked about forming a partnership with Musk to take the internet to 15,000 rural schools.

Starlink satellites differ from those deployed by the US companies Viasat and HughesNet, which are geostationary, that is, they appear fixed in the sky because their orbits accompany the earth’s rotation, at a distance of more than 22,000 miles. In contrast, Starlink employs many small satellites orbiting at only 342 miles. By October, the fleet consisted of 4,988 satellites, and the company has plans to reach 12,000 in the coming years. This has made more robust data packages available at better prices. A “Viasat Infinity” plan costs $100 to $120 a month for a data package of 160 gigabytes at a speed of 30 Mbps. On the other hand, Starlink currently charges a one-off price of $400 to purchase its equipment, followed by a monthly fee of $37—with seven times the speed.

Locals built a simple wooden structure for the Starlink equipment. The community is taking part in a project that urges conscientious use of the internet, which includes utilizing it to protect their territory. Photo: Filipe Bispo/SUMAÚMA

Four months after receiving authorization in January 2022, Starlink began operating in Brazil, first in the South and Southeast regions. At the time, Musk met with Bolsonaro and declared he was “super excited to be in Brazil for the launch of Starlink” for 19,000 unconnected schools in rural areas of the Amazon.

Super excited to be in Brazil for launch of Starlink for 19,000 unconnected schools in rural areas & environmental monitoring of Amazon! 🇧🇷 🌳 🛰 ♥️

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) May 20, 2022

Musk’s promises and apparent enthusiasm ended there. Besides the donation of antennas to just three schools in the state of Amazonas, as of June 2022, as part of a pilot program set to expire in September, no further public actions ever involved Starlink.

“Under the Bolsonaro administration, the communications minister [Fábio Faria] served as the facilitator of relations between Starlink and Anatel and expedited the authorization process, while another company [the British firm Oneweb] didn’t get a license as fast,” says Oona Castro, director of institutional development at the Center for Research, Studies, and Training (Nupef), a civic sector organization focused on the safe use of technology.

InfogrAPHIC: Rodolfo Almeida

Traditional communities tackle the State’s failure to act

For the time being, the Lula administration has pinned its hopes for the Amazon’s internet on the Connected North Program. SUMAÚMA reached out to Brazil’s communications ministry to inquire about the differences between the current program and the one implemented under Bolsonaro but did not hear back. In late September, the Lula administration also announced its National Connected Schools Strategy, which pledges to bring connectivity to all K-12 schools in the country by 2026.

Tasso Azevedo is the general coordinator and founder of MapBiomas, a collective of climate-focused nonprofit organizations and academic institutions; he is also one of the creators of the Forest Peoples Connection Network, a partnership between dozens of civic organizations and companies. The alliance intends to deliver broadband internet to 5,000 isolated villages and communities by November 2025. This is civil society’s most ambitious endeavor to bring connectivity to the Amazon region, in the face of the government’s historical omission and inability to do so.

The project took shape during 2022 and the first installation came in March of this year, under the pilot phase. Work began scaling up in June, and by late August the project had connected more than 200 villages and communities, registered over 5,000 people, and affected an estimated 15,000 individuals. Tasso explains its importance: “What are the two main demands of Indigenous, Quilombola, and Ribeirinho populations today? First and foremost, obviously, is the demarcation of their lands,” says Tasso. “Then comes connectivity. Because connectivity means improved security, access to health and education, and the ability to engage and organize.”

Júnior Nicácio Wapichana, an attorney with the Roraima Indigenous Council, says that a Starlink antenna has been installed in the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Territory. “It has made it much easier to report invasions. We’ve taught Indigenous operators to draw up denunciation protocols, and the document reaches the public security agency quickly.”

Ivo Macuxi, likewise an attorney with the Roraima Indigenous Council, points out that 99% of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory can only be accessed by air. “Internet communication is important in any kind of emergency,” he says.

Forest Peoples Connection sends communities a kit containing a customized router that creates a local network, connecting up to 300 people simultaneously, with data protection through a virtual private network (VPN). “The project wants to guarantee safe, conscious access to the internet,” says Tasso.

Each community defines their rules for using the network, and a facilitator is always chosen from among residents, someone who will be responsible for solving possible connection problems. Communities decide collectively what their rules for internet usage will be.

Illegal miners online

Ibama informed the SUMAÚMA reporting team that by late August, 32 Starlink antennas had been apprehended in illegal mining zones. There had previously been reports that criminal miners were relying on the antennas of providers like Viasat but never on this scale. When the federal police was asked how this use of the internet by miners might interfere with the force’s work and whether they were planning any actions in this regard, they forwarded the SUMAÚMA team an email stating that “it is not possible to reply, as this information could compromise the objectives of investigative actions.”

The geographer Estevão Benfica Senra, a researcher with the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), believes the transportability of Starlink antennas will tend to increase their utilization in illegal mining regions. Miners are reported to use the system especially to form networks of online groups to monitor enforcement operations and organize logistics. “Operations can no longer count on the surprise factor, so they become less effective,” says Senra.

Illegal miners exchange messages on WhatsApp groups–forest destroyers also rely on the internet, issuing alerts about surveillance operations by the Federal Police and environmental protection agency Ibama

Many offers of equipment for sale and jobs like miner or cook can be found on Facebook. Carolina Grottera, an economics professor at the Universidade Federal Fluminense, studies the mining chain in Baixo Tapajós, Pará state, in the Brazilian Amazon. She has found that “the internet contributes to the mining boom in various ways,” for example, by advertising jobs, equipment and products, and leisure opportunities. “The internet makes life in illegal mining areas more attractive because the miners can stay there for weeks at a time, while they’re not cut off from the world and their families. They can even send their families money via Pix [instant funds transfer]; they have entertainment,” Grottera says.

The internet abounds with ads in which Starlink antenna “dealers” hawk their wares. There have been reports of scams

Disinformation in the palm of your hand

In addition to concerns about criminals taking advantage of Starlink, there is also apprehension about the technology’s potential cultural impact in traditional communities. “Young people may get information that harms their family first and then their community. They might be influenced by violent content, or even recruited by organized crime. This risk is a reality. The community has to have internal control,” says Nicácio Wapichana.

Joaquim Belo, international relations secretary for the National Council on Extractive Populations, argues that this problem must be addressed. “Connectivity places us in a globalized world, and this interferes directly with the community’s life. What sustains the forest is people’s way of life, and we have to have generational concern for our young people, who are our future guardians.”

The anthropologist Fernanda K. Martins, director of InternetLab, a research center in the fields of law and technology, is beginning a study to assess the cultural and social effects of introducing Starlink in these territories. “We can’t talk about the transformations produced by the internet without talking about these impacts and without mitigating impacts that aren’t positive.”

José Carlos Galiza, quilombola leader, talks to residents of São Rosário about digital literacy: ‘Just like [Starlink] sells to us quilombolas and forest peoples, it sells to anybody.’ Photo: Filipe Bispo/SUMAÚMA

Forest Peoples Connection has a series of protocols for avoiding potential negative effects and encouraging communities to use the internet responsibly. The project has five work groups—health, education, territorial protection, entrepreneurialism, and culture and ancestry—each with its own strategies.

Concentrated in Musk’s hands

At present, Starlink operates virtually without competitors. “We’re talking about a highly concentrated scenario and a player who is not only an internet provider but who also flirts with political interests and a project of hegemony,” warns Oona Castro. The specialist cites data collection as a delicate area: “When you get on the internet via Starlink, at the very least you are providing data on access and frequency. While we have a General Data Protection Law, Elon Musk has already stated that he works with the data he receives,” says Oona Castro. “There is a set of strategic data. We’re talking about leaving these data with a private company.”

The project Forest Peoples Connections has brought the internet to 200 villages and traditional communities, positively impacting 15,000 people. Among beneficiaries is the Jabaquara quilombola community, municipality of Acará, Pará. Photo: Filipe Bispo/SUMAÚMA

Fernanda K. Martins, of InternetLab, doesn’t hide her “anguish” over the fact that Amazon’s digital infrastructure is in the hands of Musk: “By buying the former Twitter, he has demonstrated his lack of concern with issues very dear to Brazil, like climate change and the fight against hate speech.”

When contacted via email at its US address, Starlink did not respond to SUMAÚMA’s messages asking about the expansion of the internet in the Amazon. Nor did Brazil’s communications ministry.

Questioned about the possibility of blocking internet signals in illegal mining areas, Ibama said it had “started conversations with Anatel about the matter; however, no technical solution has been arrived at.” Sources within Brazilian oversight agencies confirmed to SUMAÚMA that this measure is under analysis. Anatel said “the use of satellite communications terminals in a given location does not in itself constitute wrongdoing from the standpoint of the provision of telecommunications services.”

Experts say the current law does not provide for the suspension of services and that data on access by illegal miners could instead be used in investigations. “The Marco Civil [law governing use of the internet] states that access logs must be kept for the purpose of investigating crimes,” says Ronaldo Lemos, chair of the Technology Committee of the São Paulo chapter of the Brazilian bar association, referring to the requirement that internet providers keep records of each internet access, including such information as date and time of each session.

In very isolated areas, Starlink satellites will remain the only option. Amazon, the company, plans to inaugurate Project Kuiper by the end of next year. Other satellite companies are vying for a slice of this market, including both Oneweb, which received operating authorization from Anatel in July, and Viasat, which launched a new satellite for the Americas, which hasn’t entered operation yet. Meanwhile, between euphoria and fear, Starlink continues its advance across the Amazon.

Report and text: André Duchiade and Catarina Barbosa

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Malu Delgado (news and content), Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (coordination)

Director: Eliane Brum

A resident of the Jabaquara quilombola community checks out her cell phone after installation of the Starlink antenna. Photo: Filipe Bispo/SUMAÚMA