A gesture that left a mark on history. A gesture that expressed ideas and passion with the movement of hands, arms, head, and body. A gesture associated with a tireless struggle to defend the rights of the forest, the rivers, and its peoples. A gesture that will be forever associated with one woman: Tuire Kayapó, a member of the Mebêngôkre people.

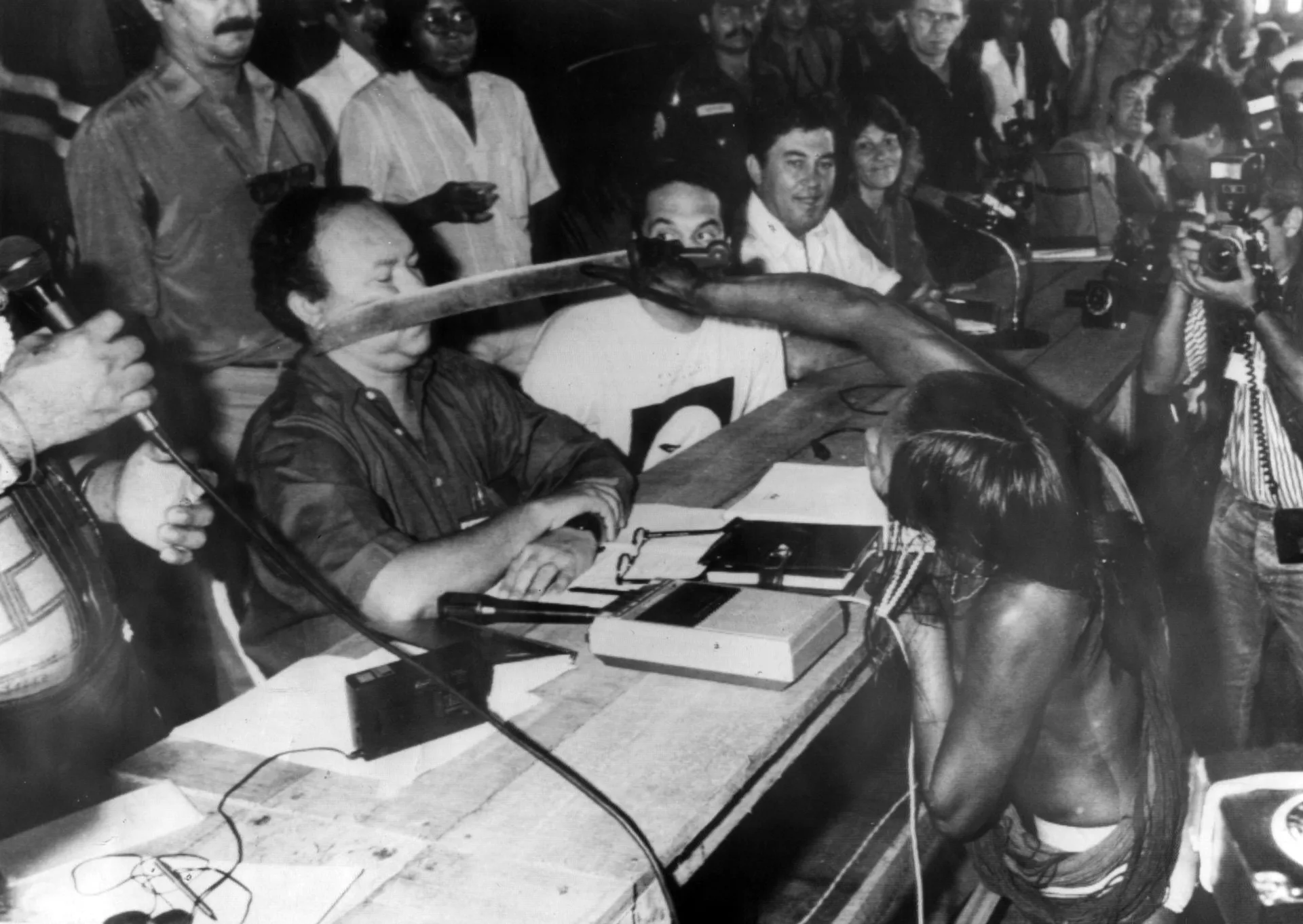

Tuire’s gesture was to lift a machete to the cheek of José Antonio Muniz Lopes, the general coordinator for the CEO of Eletronorte, in 1989. This powerful expression of defiance and opposition was aimed at the construction of the Kararaô Hydroelectric Plant, which would later become the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant, which currently pilfers and enslaves 70% of the water flow in the Xingu River to generate electricity. Tuire’s 19-year-old arm deterred a dam.

At 19 years old, Tuire put a machete to the face of an Eletronorte representative after hearing the government would build a hydroelectric plant on the Xingu River. Photo: Protásio Nene/AE

So many lives were contained in that one gesture! Tuire Kayapó’s revolt against the Kararaô hydroelectric project was not an isolated or individual act. Tuire’s machete-wielding arm carried and carries the original peoples’ insurrection against their dispossession from the time of the European invasion of the Americas. Tuire’s arm represents the blood and the memory of hundreds of years of pillaging, colonization, and territorial and cultural weakening of Amerindian collectives, expropriated from themselves by the developmentalist, sexist, slavery-supporting, and capitalist practices that continue to impact Brazilian national policy and its egotistical regime of excluding diversity.

“Not in our name,” I hear it when I look at the picture of Tuire’s gesture in 1989. A chorus of voices of the peoples of yesterday, today, and tomorrow is imposed upon the gesture of this Kayapó woman. A multitude-gesture, a multitude-people. “Not in our name,” screams the Xingu River against Kararaô and Belo Monte, those engineers of death and confiscation of life’s creative energies and creators. Tuire’s multitude-people-gesture neither begins nor ends in 1989.

This gesture starts before recorded history in the mythic narratives of time immemorial, conveyed and refined through the generations by Mebêngôkre women and men, including Tuire. This is expressed as iarem tum, [“ancient speech from ancient people” in the Mebêngôkre language]. In this time, communication abounded between what we have agreed to call different species – animals, humans, plants, rivers, winds, stones. In certain situations, people could alter their bodily forms, alternating between these different bodies. People becoming animals becoming people becoming plants becoming animals becoming people, becoming. This conversion marks Tuire’s people’s knowledge and respectful relationship with the forests, animals, plants, rivers, winds, rains. A plethora of conversations were held with the fish-people who gifted Tuire’s ancestors with beautiful names, songs, and dances for the ritual festivals. The children with these beautiful names had to be celebrated. The children had to be celebrated. Life had to be celebrated and defended.

The Mebêngôkre, like Tuire, do not grow alone. They are made by women’s hands: by the hands of their mothers, aunts, grandmothers, by the hands of formal friends, ones who act as godmothers, people who draw closer to one another, creating bonds of mutual affection, respect, and care. As the people grow, drawings are frequently applied by painting their bodies with an ink of genipapo and achiote. Black and red ink applied symmetrically. This continual process of body manipulation begins a few months after birth and carries on until a person’s physical death. It is seen on the hands of the painterwomen, blackened from their continued use of genipapo ink: the art of acceptance and the body’s beauty belongs to them, the ones responsible for continually strengthening the bodies and souls of all the people around them. We look at the picture of Tuire’s gesture in the city of Altamira, in 1989: it is her genipapo-blackened hand that holds the machete.

I never spent time with Tuire Kayapó, but it is as if I had. Her presence is in every Indigenous person, in collectives of Ribeirinhos and Quilombolas. Her presence is in those who step with respect across the forest’s ground. Her presence is in those who defend the socioenvironmental cause and know the weight of the term climate emergency. Tuire’s presence is in all my friends of the Mebêngôkre-Xikrin people of the Trincheira Bacajá Indigenous Territory. Tuire’s existence was, is, and will continue to be shared, extended, and spread. A multitude-existence. So much so that many times I feel I could nearly touch her hair.

In 2012, when construction began on the Belo Monte dam wall splitting the Xingu River, I had this feeling. I felt Tuire’s hair close to my hand. I was in the company of some of my Mebêngôkre-Xikrin friends in Bacajá Village, now called Pukatum (old land, old ground). We were in a canoe, with an outboard motor on the back, navigating along the Bacajá River. We navigated to a part of the forest. We were looking for the bark of a tree used for charcoal to make the genipapo ink used to apply drawings to bodies. Mopkure, one of my formal friends, patiently cleaned out her pipe, clogged with the remains of the previous night’s tobacco. At our side, along the riverbanks, dozens and dozens of yellow-spotted river turtles of all sizes were sunbathing. Some on top of the others, they balanced on fallen tree trunks along the riverbank. Two baby turtles seemed to be playing. Irekà, a wife, grandmother and an auntie to many children, stared at that scene: baby river turtles free, with no knowledge of the tragedy, the catastrophe, the disaster that would lay waste to them when Belo Monte imposed a perennial drought on the Volta Grande do Xingu – the river’s big bend region. How much is life worth? How many kilowatt-hours is life worth?

“We’re going to hit the [Belo Monte] dam boss and we’re going to cut his ear. We’re angry. We’re not playing. Let’s talk tough against the dam. We’re going to take the keys to the [Belo Monte’s] machines and we’ll never give them back,” said Irekà one of my Mebêngôkre-Xikrin friends. I told this story in my doctoral thesis; I wanted people to hear these words. Irekà also said the “dam is punure [ugly, horrible], the river turtles will die, their babies will die, the water will dry up, there will be no more water for bathing. The dam is punure, the women don’t want the dam.”

Irekà’s frightening vision became a sad reality. More and more of the Bacajá River’s yellow-spotted turtles are disappearing year after year. I learned from a collaborative research collective called Mati (or the Independent Territorial Environmental Monitoring group) that the turtles’ disappearance is an important scientific indicator of serious environmental disturbance. People like Tuire and Irekà always knew this.

May we increasingly join the uprisings of women against the dispossession of life. We stand with Tuire, machetes in hand. What will remain for our daughters, our sons, our grandsons and granddaughters? What life will be left from the plundering perpetrated by white men and their greedy monochromatic uniforms?

On that day, inside a canoe on the Bacajá River, in the company of some of my Mebêngôkre-Xikrin friends, I nearly touched your hair, Tuire. You were there. You’re still there. You will always continue to be there, in that canoe and in thousands of other canoes, machete in hand against the greed and selfishness, together with so many people’s arms, with the arms of those who, like you, know that tough talk is needed against Belo Monte.

Thais Mantovanelli lives in Altamira, Pará, almost at the edge of the Belo Monte reservoir, where the Xingu River’s waters are enslaved. She is an anthropologist with the Xingu Program at Instituto Socioambiental and completed her PhD in the Social Anthropology graduate studies program at the Federal University of São Carlos. She has been following the struggle of Indigenous peoples and Ribeirinhos against the impacts of the Belo Monte Dam since 2011.

Tuire (middle) and her fight became a symbol of Indigenous women’s resistance. Photo: Carl de Souza/AFP

Text: Thais Mantovanelli

Editing: Eliane Brum

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Douglas Maia

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation:Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation:Sarah J. Johnson

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum