Wenatoa Parakanã left her daughters, ages two and 16, in her village in the Brazilian state of Pará to travel 12,000 kilometers to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, where she was able to personally deliver her request for the government to remove invaders from the Apyterewa Indigenous Territory to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Their removal began in early October, by order of the Federal Supreme Court, but it is facing opposition from local politicians while it drags on. The Parakanã, who are hunters, can now only circulate in around one-fifth of their territory. “Our grandparents hunted by staying in the forest for weeks with their families, but today we no longer do this, because the invaders are taking everything,” says Wenatoa, at one of the debates she took part in at this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, the COP-28, held in Dubai from November 30 to December 13.

Like Wenatoa, Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva, the head of the Brazilian delegation, and her team of negotiators faced a daunting meeting in Dubai. During the conference, they bent Brazil’s position on a topic that has, over the last 31 years, since the Climate Convention’s approval, been the elephant in the negotiation rooms: ending the production and use of fossil fuels, the main culprit behind the planet’s heating. If by mid-November Brazilian negotiators were avoiding the subject and claiming it was not on the official COP agenda, in Dubai they were talking about “confronting” the issue and working to include it in the Global Stocktake, the main document approved at the conference.

In a December 9 speech, Marina proposed creating an instance within the Climate Convention for negotiating a timeline to “take our foot off the accelerator on fossil energies,” with “developed countries leading this deceleration process.” On December 11, two days before the conference ended, she said that it was necessary to “assimilate this undeferrable theme:” “We don’t want a tidal bore of pressure at COP-30 of something that was not digested during the process,” she said, referring to the conference to be held in Belém, in 2025.

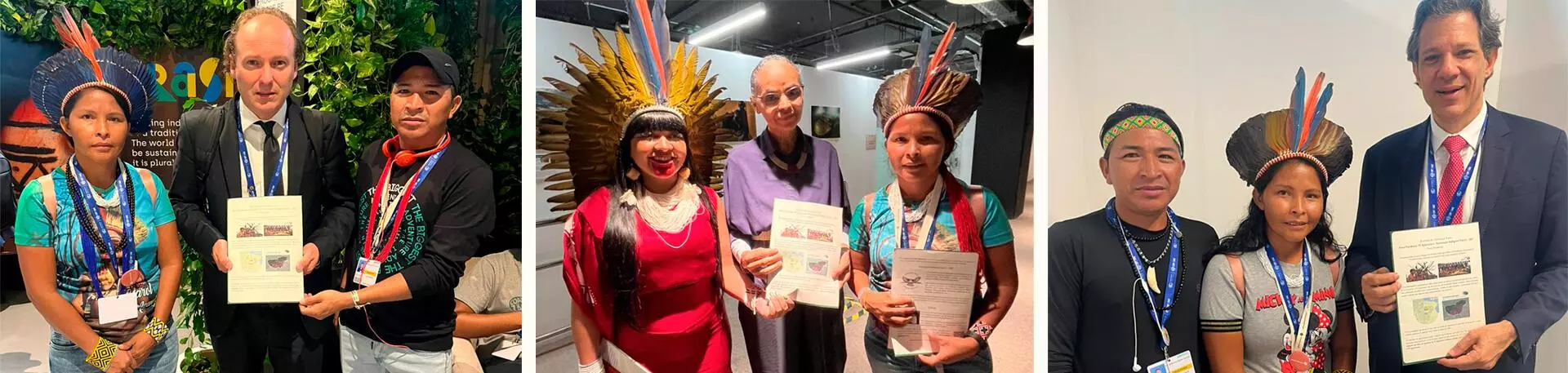

WENATOA PARAKANÃ HANDS A REQUEST TO REMOVE INTRUDERS FROM THE APYTEREWA TERRITORY TO RODRIGO AGOSTINHO (REPRESENTING BRAZIL’S ENVIRONMENTAL AGENCY), ENVIRONMENT MINISTER MARINA SILVA, AND TREASURY MINISTER FERNANDO HADDAD. PHOTO: TATO’A INDIGENOUS ASSOCIATION

It is, however, most likely that tidal bores will surge forth in the two years leading up to Belém.

The Dubai agreement “calls” on countries to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.” The language in the text is intentionally vague, opening the way for endless tugs-of-war. It establishes no clear guide for making it possible to reach 2050 with a radical reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, funds for countries with fewer resources to make the energy transition will only be discussed in 2024.

Domestically, the Lula administration will be under growing pressure to show internal coherence and to set aside a project of pumping “every last drop of oil.” Indigenous people are demanding that policies to demarcate and protect their territories be included in new targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that Brazil, like all countries, will need to submit by 2025. The newest idea floated by the government in Dubai – the creation of an international fund that pays for tropical forests – was presented in its very early stages and will need to be put into practice.

Marcio Astrini, the executive secretary of the Brazilian Climate Observatory, points to an incoherence between the meager mandates in the Dubai agreement and the need, which the text recognizes a multitude of times, to keep the planet’s temperature from rising above 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to preindustrial levels. Exceeding this limit, which many climate scientists feel is already certain, could make life unbearable. “The commitments won’t be fulfilled by just hoping countries have good sense. If there isn’t a growing movement in public opinion, in civil society, holding those with more responsibility to account, and that includes Brazil, it will never become a reality,” says Astrini.

SHIRLEY KRENAK, SILVINHA XUKURU, AND INGRID SATERÉ MAWÉ AT THE COP, WHERE INDIGENOUS REPRESENTATION WAS MOSTLY FEMALE. PHOTO: DANIELE GUAJAJARA AND KEILA GUAJAJARA/ANMIGA COMMUNICATORS

The creation of the instance suggested by Marina to discuss ending fossil fuels was not approved. However, the Global Stocktake tasks the hosts of COPs 28, 29 and 30 – the United Arab Emirates, Azerbaijan and Brazil, all oil-producing states – with coordinating and implementing the Dubai conference’s decisions, in what is called the “Road map to Mission 1.5.” It’s an almost impossible mission. Kevin Anderson, a professor of energy and climate change at the University of Manchester, in the United Kingdom, points out that if the world were to maintain current emissions levels, it will heat by more than 1.5 degrees in the next five to eight years. “Even if we seriously began to cut emissions from the start of 2024, and there’s no such requirement in the new [Dubai] text, then we’d still need zero fossil fuel use, globally, by around 2040,” he told British website Science Media Centre.

The Lula-Marina double-act

By setting the tone for Brazil’s positions in Dubai, Marina Silva has taken something Lula said and stuck to it as if it were a lucky charm: “It’s time to confront the debate on the slow pace of decarbonization of the planet and to work for an economy less dependent on fossil fuels,” the president said at a speech on December 1, the first of two days at the COP dedicated to speeches by government leaders.

This was how the minister indirectly responded to the news that had blown up on the eve of that same day, coming from Minister of Mines and Energy Alexandre Silveira, that Brazil would enter OPEC+, a group of countries allied with the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. “The question of fossil fuels is at the heart of everything we’re facing in the world, and President Lula had the courage to bring this topic up at the start of the conference,” Environment Minister Marina Silva said.

When asked by SUMAÚMA at the end of the COP whether Lula said this at her suggestion, she said no: “He said that, but it’s not detached from the work done here. It’s not something we invented here.”

The minister was not, however, able to respond to the many questions she was asked about not only the country joining OPEC+, but also about plans to explore oil off the Amazonian coast and about the mega auction of exploration blocks held in Brazil on December 13, the last day of the COP.

In these cases, the most she had to say is this debate would take place from here on, when “the public and private sectors will have to translate the commitment we undertook in their actions and their planning.” She said that in the case of the government, the debate “needs to be held by the National Council on Energy Policy, which will certainly consider what was approved here.”

The Council, on which sixteen ministries hold seats, is headed by Mines and Energy Minister Alexandre Silveira, who is keen to increase oil and gas production. On November 30, in Dubai, he said he was opposed to Council discussions on the pace of oil exploration. “I’m extremely opposed to prohibition by the National Council on Energy Policy of oil exploration,” he said. “The national policy is well-defined in this sense, provided it complies with environmental law, provided it stays in an area that can be explored,” he added.

Bucket of cold water

On December 2, Wenatoa Parakanã was with Lula in Dubai. At a meeting between the president and representatives from 130 civil society organizations, she handed him a leaflet in which Apyterewa Indigenous people ask for support to “restore their sovereignty” over the territory that has been named “the most deforested in the Amazon.” At the meeting, Minister Márcio Macêdo, the Secretary General to the President, made a promise in front of everyone that the removal of the invaders will be completed.

LULA, HELD TO ACCOUNT AT A MEETING WITH CIVIL SOCIETY, FIRED BACK WITH HIS OWN CRITICISM AND THREW A ‘BUCKET OF COLD WATER’ ON THE AFFAIR BY CONFIRMING THAT BRAZIL IS JOINING OPEC+. PHOTO: RICARDO STUCKERT/PR

At the meeting, there were many other demands from civil society but the president was curt. One participant described the responses and the decision to join Opec+ as a “bucket of cold water.”. In a packed room, before young people, Indigenous peoples, activists from the black movement, and environmentalists, Lula heard an appeal from the Brazilian Climate Observatory’s Marcio Astrini to bring a timeline proposal to the negotiating table to gradually eliminate fossil fuels. The president answered that “getting rid of fossil fuels is a desire, but it’s a war, a fight.” And, after a suspenseful pause where he started by saying that “Brazil will not be part of OPEC,” he made his final decision: “Brazil will be part of OPEC+.” He claimed the nation would join to convince the group’s countries that “they need to reduce fossil fuels” and invest in renewable energies in Latin America. Nobody was convinced.

Two days later, on December 4, Brazil won the Fossil of the Day, a satirical award given out by the Climate Action Network, whose members include over 1,900 socioenvironmental organizations in 130 countries. The network recalled that Lula had promised to be “a climate champion”, but his administration appears “to have mistaken oil production for climate leadership.” A civil society observer with access to the negotiations said that the satirical award was a “reality shock” and contributed to the shift in Brazil’s diplomatic position.

At the meeting with Lula, it was up to Dinamam Tuxá, the executive coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Apib), to vocalize this group’s demands. “You signed a commitment with us,” he recalled, asking for rapid demarcations of territories and support to prevent Lula’s vetoes of the historic cut-off point from being overridden by Congress. The president had an ask of his own. He said the social movement should mobilize to elect a less conservative legislature.

It was as if he were predicting his defeat on December 14, one day after the COP ended, when Congressional members overrode his vetoes. Based on the “Marco Temporal” law, the thesis of which was ruled unconstitutional by the Federal Supreme Court, demarcation can only happen in territories that were already occupied or disputed by Indigenous people as of October 5, 1988, the date of the Constitution’s enactment.

Because they demand to be treated as participants, with decision-making power, Indigenous participants are waiting to see how references to them in the COP-28 documents will be translated into practice. Chief among these is the Global Stocktake, which makes nine mentions of the rights and participation of native peoples. The biggest new aspect in relation to previous UN texts is recommendations for countries to take the Indigenous vision of the world and Indigenous values and knowledge into account in policies to stop climate change.

Shortfall in forest funding

On December 8, at a COP debate on the role Indigenous territories play in preserving biodiversity, Wenatoa Parakanã made an appeal: “Our trip here to COP is to ask for support in recovering what has been destroyed, so our animals live well afterward, like us human beings. (…) Planet Earth is like a mother who is pregnant. For the child to be well, the mother must be well. Our planet must be well for us to be well. If the pollution, deforestation, water contamination continue, there will be no future for human beings.”

At a conference marked by the issue of fossil fuels, preservation of forests like the Amazon took a back seat – even though the two issues are closely connected. According to climatologist Carlos Nobre, who was in Dubai, if the planet’s temperature rises by 2.5 degrees, the forest will pass the point of no return, degrading until it loses its ability to absorb carbon gas and regulate the climate.

In the Global Stocktake, the two paragraphs discussing forests boast the unprecedented inclusion of a goal to reach zero deforestation by 2030. The language, which uses verbs like “notes” and “emphasizes,” is weaker than the proposal from Brazilian negotiators, because it does not result in a firm commitment from countries. For the first time, the document also connects the conservation of biodiversity and the forest. This is important because during climate negotiations forests tend to only be seen for their ability to absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

Ruth Davis, a specialist from the Smith School of Enterprise and Environment at Oxford University, says that passages on forests could have been improved if they had established a program to finance forest conservation. She did the math and concluded that all the commitments on tropical forests announced in Dubai added up to just US$ 400 million. This is far short of what is needed. In 2022, the 15th UN Biodiversity Conference, held in Canada, estimated that US$ 200 billion is needed annually for nature conservation.

Ruth says that Brazil’s proposal to create an international fund to compensate countries with tropical forests is welcome. The fund, which aims to avoid carbon market logic, would be called the Tropical Forests Forever Facility. The idea, presented at the COP by Garo Batmanian, the director of the Brazilian Forest Service, is to make fixed-sum annual payments per hectare of forest. “The forest is more than carbon; it’s climate regulation, it’s the people that live there,” Garo said. For Ruth, the “hard work” of getting the fund up and running starts now. “Brazil needs to do a good deal of diplomacy to build support before the COP-30,” she says.

Despite mentioning the forests, the documents approved at the COP failed to touch on the extensive livestock farming and agricultural monocultures that are at the root of deforestation. The Global Stocktake cites the goal of reducing emissions of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, but in the context of the energy transition and without mentioning the gas released by cows belching. The agricultural sector trails forest destruction as the second largest source of emissions in Brazil, releasing 27% and 48% of emissions respectively in 2022.

Belém: More lobbyists or back to basics?

The Dubai COP was gigantic. The most recent numbers from the UN tallied 85,000 participants, over 3,000 of whom were Brazilians. The conference was a huge trade show, with 2,456 lobbyists from the fossil fuel industry, according to a count by a network of NGOs that go by the name Kick Big Polluters Out, and 340 representatives from agribusiness companies, as counted by the website DeSmog, including Brazilian company JBS.

Susana Muhamad, Colombia’s environment minister, hopes that the COP-30 is a Latin American COP, where ‘the power is nature’s.’ Photo: Thaier Al-Sudani/Reuters

The economy in Dubai, one of the seven Emirates, is increasingly based on business events, upscale tourism, and the second home real estate market. The COP was held in Expo City, a theme park intended to simulate a “city of the future” that opened in 2021. The bathrooms and internet connection were unimpeachable. Ty’e Parakanã, a cacique, noticed that “despite the pollution” in the city’s air, the streets were free of litter and there were no wires hanging from light posts. “Clothes stay clean,” he said.

Belém, with its precarious hotel and transportation infrastructure, will be unable to replicate this model. But it’s not just a Brazilian problem. In one of its Eco newsletters, released daily during the COPs, the Climate Action Network argued that holding smaller conferences could be feasible for more countries, which need to use the money they have to confront the climate crisis.

Tasneem Essop, a South African and long-time socioenvironmental leader who serves as this international network’s executive director, said that it will be great if Brazil “wants to go back to basics, discuss the climate crisis, and not hold an expo.” The symbolism of this could affect how the environmental emergency is treated. “A COP that goes back to basics should discuss the people affected by climate change,” Tasneem said.

Our coverage in Dubai is in partnership with Global Witness (@global_witness), an international NGO that has been investigating, exposing, and campaigning against environmental and human rights abuses around the world since 1993

Report and text: Claudia Antunes

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Julieta Sueldo Boedo

English translation: Sarah J. Johnson

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Malu Delgado (news and content), Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (editor-in-chief)

Director: Eliane Brum