On Sunday, February 11, day two of Brazil’s five-day Carnival extravaganza, the Yanomami people will be honored at the samba parade by Salgueiro, one the oldest, most venerated samba schools in Rio de Janeiro. Entitled Hutukara—a reference to the ancestral sky that fell over Earth in primordial time, forming the virtual forest covering our planet today—Salgueiro’s theme song is possibly one of the loveliest, most moving Carnival anthems in recent times. And for anyone who has followed the escalation of the humanitarian crisis in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, the song is a balm for the soul.

One line of the Salgueiro refrain is sung in Yanomae, one of the six languages of the Yanomami family: “Ya temi xoa, aê, êa! Ya temi xoa, aê, êa!”—which can be translated as “I am still alive.” The word temi not only means to be alive but also to enjoy good health, physically, mentally, and emotionally. This powerful refrain underscores the immense resistance of the Yanomami people and their determination to fight back against the genocidal project conducted by non-Indigenous society for decades—an endless war since first contact, one that has grown more dramatic with the rise to power of the contemporary far right.

Because a Public Health Emergency of National Concern was declared one year ago in Yanomami Indigenous Territory (YIT), the hope for 2024 was that the samba would ultimately be sung in celebration of a new cycle of well-being and prosperity for the Yanomami people, with the forest effectively protected and full recovery of the health of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana (Indigenous people who inhabit part of Yanomami lands in Brazil and Venezuela). Unfortunately, this is not yet the case.

The latest data presented by the government on the health picture in YIT leaves no doubt: the administration has not kept its pledge to restore dignity in Yanomami lands. Sadly, the December bulletin of the Health Ministry’s Center for Emergency Health Operations registers numbers similar to those of the previous government. From January 1 to November 30, 2023, 308 deaths were reported in YIT, most from preventable health problems and diseases, such as diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria. While numbers are still not in for December 2023, it is likely that the statistics for the last year of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro’s term and Lula’s first will be close. In 2022, 343 deaths were recorded through the end of December.

Of the 308 deaths from January 1 through November 30, 2023, 52.2% were children under the age of five. There were more than 25,000 cases of malaria, an average of 2,000 per month. The Lula administration has clearly not done enough to change this situation, which took shape during the criminal management of Indigenous health under Bolsonaro.

Aerial view of an illegal mining site in Yanomami Indigenous Territory, February 2023. Photo: Alan Chaves/AFP

The current administration’s health indicators suggest there is still a serious lack of care, largely echoing what happened in the previous four years. Basic flaws in the healthcare model are being repeated, including the lack of regular visits to villages by healthcare providers (exacerbated by security issues), supply and structure problems at Basic Indigenous Healthcare Units, and faulty epidemiological surveillance work.

What explains such a remarkable failure? Obviously, the government knew it would be held accountable for its promises to the Yanomami people. So I don’t believe it failed intentionally. I trust that President Lula, given what he saw in the state of Roraima, has been truly moved by the Yanomami plight. But, as we know, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. It is not enough to want to change a situation; you have to get to know it. Particularly a situation as complex as the one in YIT.

The first, and perhaps most important, mistake made by the government was not to create a body with the power to coordinate the emergency response across government agencies. We know that the root of the Yanomami crisis lies in the interrelation between two major concerns: (1) the advance of illegal mining operations and (2) the weakening of the healthcare system through the political and administrative destruction of the Special Public Health District for the Yanomami Indigenous Land, two problems that feed off each other, intensifying the impacts of both. To stabilize the public health and political picture in these communities, the government would ideally: (1) enforce operations to neutralize illegal mining; (2) support vulnerable communities through the provision of regular food assistance, farm tools, and seeds; (3) send in healthcare missions; and (4) re-establish regular healthcare services. As reasonable as this sequence of actions may be, no such coordinated initiatives were undertaken in any of the more sensitive regions of YIT. Consequently, rates of socioeconomic and public health vulnerability are high across most of the region, accompanied by a lack of adequate emergency support and regular healthcare.

The Executive Office of the President could have played this role but failed not only to coordinate these actions efficiently but did not even properly monitor the progress of plans. The office’s indifference to the Yanomami is visible in the administration’s interministerial plan, a document with no targets, indicators, detailed timetable, budget, or assignment of responsibilities. So if an initiative missed the mark, the government’s top management would not even be in a position to assess progress and propose any needed corrections.

The lack of effective coordination also resulted in human resources and time being wasted on the production of diagnoses and studies that did little to solve the real challenges in YIT, that is, logistics, the fight against malaria, protection strategies, infrastructure development, and so on. A prime example is the absence of a logistics study to help efficiently plan and then fine-tune the dispatch of supplies and personnel to healthcare posts. The aircraft fleet used by the Special Office of Indigenous Health is so disorganized that it astonishes someone who has followed this matter for more than ten years.

Logistics, as a key issue in Yanomami lands, should have formed the backbone of any plan to restructure the State’s presence in the territory. Yet, to the contrary, it became the subject of a tug-a-war between the Indigenous health office and Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs Funai, with neither of the two agencies managing to offer a coherent solution. It took months to reach an agreement about refurbishing five airstrips, while more than forty airfields are in urgent need of maintenance and expansion. To give an idea, some communities that had previously been served by small planes now rely exclusively on helicopters, aircraft that are nearly four times as expensive in terms of flight hours.

These logistical deficiencies left the government in the hands of the Armed Forces, which spent millions of dollars dropping packages of food staples into villages and clearings, following no particular criterion. Not to mention the tons of food abandoned in city warehouses because the military spent the funds available for air freight before it distributed the target number of food parcels stipulated by Funai.

In fact, anyone who has studied a little about the recent history of the Amazon would know that the Armed Forces have never exactly been allies of the Yanomami and that relying on their goodwill to solve a problem they helped create, by commission or omission, would be a risky bet to say the least.

In the first half of 2023, a small group from Brazil’s environmental protection agency Ibama, acting with the support of the federal police sometimes and of the Federal Highway Patrol’s tactical group at other times, took heroic action against several illegal mining operations spread across the Yanomami forest. Along with other proposals aimed at disrupting the illicit mining sector’s logistical operations, Ibama managed to drive out a large part of the invaders, significantly reducing the number of deforestation alerts issued through June 2023.

Starting in August, however, Ibama staff were moved to other regions, and the Army began playing a greater role in the repression of illegal mining activities and the control of river channels. Initiatives gradually grew both less regular and less effective, sending the criminals a message that the government was running out of steam.

The Yanomami Indigenous Territory soon saw a new wave of invasions. The Yanomami reported that illegal miners were resisting or returning by river, land, and air in at least 15 regions of their territory. From October to December of 2023, the Yanomami of the Palimiu community observed the daily traffic of miners passing through a makeshift barrier on the Uraricoera River. While soldiers were sleeping in their tents along the Palimiu landing strip, far from the river they were supposed to be guarding, every morning between 4:30 and 6:30 the miners religiously made their way under the steel cable that supposedly restricts entry to the region.

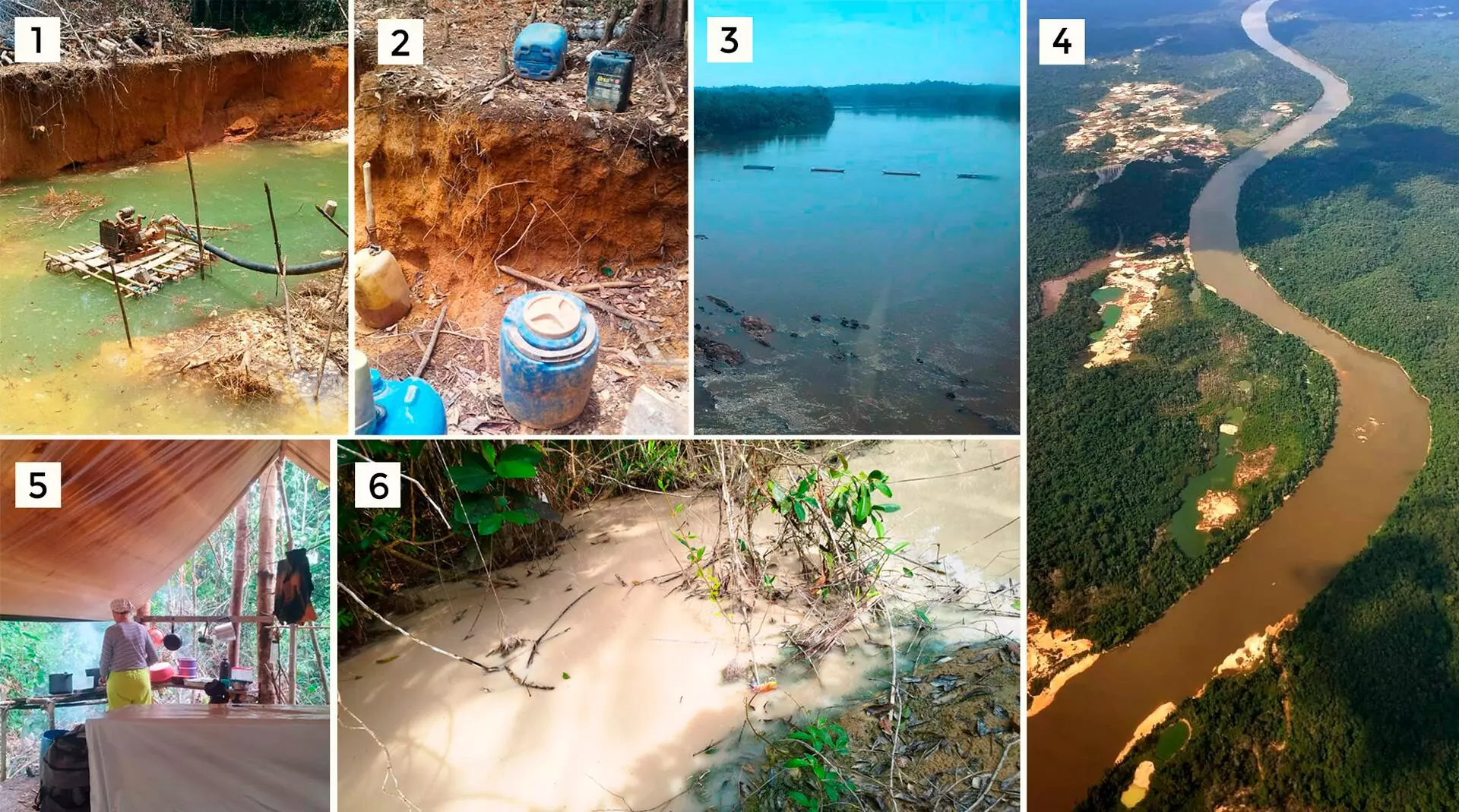

1, 2, 5, and 6: Signs that illegal miners have returned to the Papiu region, where operations had decreased in the second half of 2023. Photos: Yanomami people. (3) Makeshift barrier on the Uraricoera River, November 2023. Photo: Marcelo Moura. (4) Active mining operations on the Uraricoera River. Foto: Evilene Paixão/Hutukara

Some of the boats went upriver to supply camps of miners with known ties to organized crime. At no point during the YIT public health emergency did criminal factions withdraw from their gold and cassiterite operations in the area, where they also provide regional logistics and armed security.

A little downriver from Palimiu lies a community called Korekorema. Its leaders have reported that malaria is running wild there and children are dying because healthcare teams haven’t made any regular visits in months. For their part, healthcare agents claim they can’t reach the community by boat because the river is controlled by criminal factions and so they fear for their lives.

Meanwhile, in Brasilia, Funai is arguing in court that security considerations keep it from building a Protection Base on the Uraricoera River, even though a court ruling has been in place since 2018 requiring the Brazilian State to do so. (Well, there’s no security because there isn’t a base, not the other way around.)

Over the course of the first year of the public health emergency, a kind of paralysis took hold of the Brazilian State, while the crisis festered away, an open sore for all to see.

As the lights went out on the sad year of 2023, Davi Kopenawa, shaman and chief leader of the Yanomami people, journeyed to Brasilia to take part in yet another meeting of Lula’s Council for Sustainable Social and Economic Development. The shaman had hoped to bring this state of paralysis to the president’s attention and exact a recommitment to the pledges made in January 2023. Unfortunately, Lula arrived at the event too late and Davi was unable to convey his concerns face to face. On our way to the airport for his return flight to Boa Vista, capital of Roraima, I asked Davi if he was tired of making so many trips with such frustrating results. He paused before answering and then replied: “Ma! Ya temi xoa.”—“As long as there are Yanomami, I will keep on fighting.”

Estêvão Benfica Senra is a geographer who holds a doctorate in Sustainable Development from the University of Brasilia. He has worked with the Yanomami people for over ten years. He is currently a researcher at the Socioenvironmental Institute.

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editors: Viviane Zandonadi (editorial workflow and copy editing), and Talita Bedinelli (editor-in-chief)

Director: Eliane Brum