On the one hand, two wars—Russia in Ukraine and Israel in Gaza—are further dividing governments and reminding us that armies are responsible for 5.5% of the greenhouse gas emissions now heating up the planet, as estimated in a study by the U.K.-based organization Scientists for Global Responsibility. On the other hand, the climate emergency is no longer a prediction about the future but an immediate threat—temperatures this year reached record highs, as measured since 1850, the reference year used by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Caught between these two competing issues, representatives of the nearly 200 countries who are signatories of the UN Convention on Climate Change will gather between November 30 and December 12 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. In hopes of tipping the balance, Pope Francis, who in 2019 organized a meeting of Catholic leaders to discuss the Amazon and who has released two encyclicals about preserving “our common home,” had planned to be present for the first time at an annual climate conference, this one the 28th session, known as COP28. However, doctors have warned him against traveling to Dubai as he is recovering from a respiratory condition. President Lula will also attend the “high-level segment,” which brings together government leaders during the early days of the meeting.

If COP climate conferences have tended to be bubbles where negotiators hole up inside closed rooms, protecting themselves from the pressure exerted by those on the streets, the bubble will have additional layers in the UAE, a country that restricts freedom of expression, association, and assembly, according to human rights organizations such as Amnesty International. In a statement released in August, the local government promised there would be space for climate activists to “make their voices heard.” Thousands of representatives of social movements and NGOs, including Brazilians, will be in Dubai to test this pledge, vying for space with lobbyists who act for the fossil fuel sector and other major polluters.

Mariana Belmont, a Brazilian journalist who for years has worked with the issue of environmental racism—the disproportionate impact of the destruction of nature on low-income and Black, brown, and Indigenous communities—attended last year’s COP and will go again this year. A member of the board of the Latin American movement Nuestra América Verde (Our Green America) and also of the Rede por Adaptação Antirracista (Network for Antiracist Adaptation), Mariana defines the summit in these terms: “It is a mostly white event, with white men, a lot of white civil society, where white men are in the decision-making rooms deciding for and about countries, without taking people’s lives into account.”

Stocktaking of the Paris Agreement is the crux of the conference

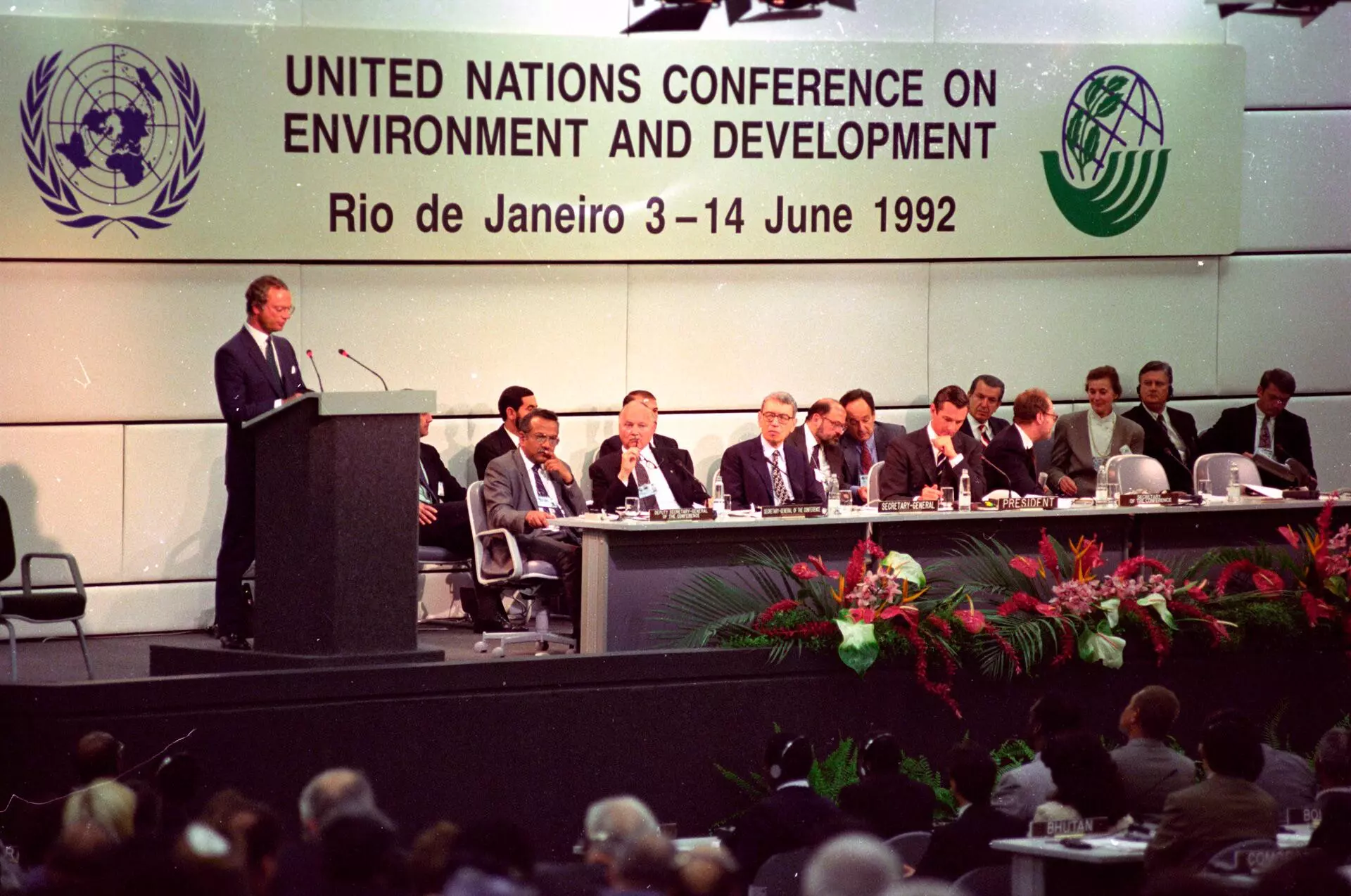

The Framework Convention on Climate Change was approved at the UN in 1992. The document, which pledged to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic [i.e., human-caused] interference with the climate system,” entered into force in 1994, and COP climate conferences have been held since 1995.

First steps: 31 years ago, Rio de Janeiro hosted the Earth Summit, where countries signed the UN Convention on Climate Change. Photo: Luciana Whitaker/Folhapress

In 1997, the climate convention served as the basis for the first greenhouse gas reduction agreement, the Kyoto Protocol. The treaty set binding targets for 37 countries classified as “developed” but was never ratified by the United States, then the world’s biggest polluter. The most ambitious product of the climate negotiations was the 2015 Paris Agreement. Under this accord, all signatory countries agreed to establish national greenhouse gas reduction targets, called National Determined Contributions, or NDCs.

In the text of the Paris document, countries pledged to hold the increase in the planet’s average temperature to “well below 2oC” and to “pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels.” For scientists, however, it has now become clear that any increase of more than 1.5oC will have dire consequences. Yet given current targets for reducing emissions, temperatures are expected to rise 2.6oC by the end of this century.

The main challenge at COP28 will be to approve a document called the Global Stocktake, or GST. Negotiations over the text are based on a technical report released in September, which advised that phasing out oil, gas, and carbon is “indispensable” to fulfilling the Paris Agreement, since the burning of these fossil fuels for transportation, power generation, and industrial purposes is responsible for releasing into the atmosphere most of the gases that cause global heating. In the GST, countries will assess compliance with the Paris Agreement and propose new actions. But so far it is not known whether or how the elimination or reduction of fossil fuel consumption will come into play in the document.

The assessment will underpin important decisions to be made at the next two COPs. In 2024, a new financing structure will be defined for tackling climate disruption and, in 2025, when the Paris Agreement turns ten, countries will have to present bolder targets for reaching net zero, that is, the state when the level of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere is balanced by nature’s absorption of them.

Brazil aims to build bridge to Belém

In two years’ time, Brazil will host COP30 in Belém, in the Amazon. To ensure the success of coming conferences, Dubai must reap good results, and so the Lula administration has put itself forward as a mediator at this year’s gathering, bearing in mind that COP documents must be adopted by consensus. “Brazil is absolutely determined to be the country that wants to lead, talking to everyone and trying to unblock negotiations as much as possible,” said André Corrêa do Lago, Secretary of Climate, Energy, and the Environment with Brazil’s Foreign Affairs Ministry. Brazil will be the “champion of 1.5 degrees,” Lago said. “A lot of people are discouraged, but we don’t want anyone to get discouraged.”

Brazil has made an official proposal for the GST called “mission 1.5,” very much focused on “positive incentives”—read “money.” At the 2010 COP, materially wealthy countries pledged annual funding of $100 billion to help other countries transform their economies so they could emit less greenhouse gas while fighting poverty. This promise was never fulfilled. If everyone is to present more ambitious, feasible targets in 2025, it is necessary to think big, according to Túlio Andrade, head of the Climate Negotiation Division with Brazil’s Foreign Affairs.

“If science says the risk is existential, it doesn’t make sense to work with limited resources. There has to be an unprecedented mobilization, as in other emergency moments, such as the pandemic and after World War II, with the Marshall Plan,” said Andrade, referring to U.S. aid for the reconstruction of European allies.

Brazil updated its climate targets this November, committing to cut emissions by 48% by 2025 and 53% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

Race against time: devastated forest in Autazes, in Amazonas state, in September. Deforestation rates began falling in 2023, but Brazil needs to do much more. Photo: Michael Dantas/AFP

Government positions itself like an ostrich on fossil fuels

If deforestation is a cursed inheritance that the Lula administration is beginning to deal with, the big thorn for Brazilian negotiators is the matter of fossil fuels— in practice, the main subject at COP28. Civil society organizations, scientists, and the UN secretary-general, António Guterres, from Portugal, have been pushing for a phase-out plan for oil, gas, and coal.

Starting with the United Arab Emirates, most countries that are major fossil fuel producers or consumers seem intent on beating around the bush, without truly committing to a phase-out. Instead, they talk about tripling the use of renewables and doubling energy efficiency, that is, achieving the same results, like manufacturing a product or lighting a house, with half the energy.

Brazil is the world’s ninth largest oil producer, and the Lula administration plans to boost production, not for domestic consumption but for export. With the COP discussion at hand, however, Brazilian negotiators have decided to make like ostriches, burying their heads in the sand in hopes they won’t be noticed. “Brazil is not a key player when it comes to oil; oil countries look at us and don’t even put us on the list,” said André Corrêa do Lago, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Pink badges and much ado for little

The official Brazilian delegation to COP28 will have around 2,000 members. Of these, some 400 will be federal authorities and public agency staff. Others will include governors, mayors, representatives of NGOs and social movements, scientists, scholars, and business people.

The composition of the official delegation is back to what it was before Bolsonaro, whose administration excluded most socioenvironmental experts and activists. This means even people who are not part of the Brazilian government’s negotiating team will receive “pink badges,” allowing them to enter closed-door negotiation rooms.

Toya Manchineri, head of the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB), will attend COP this year for the fourth time. COIAB received five pink badges from the official delegation but will have a total of 16 people at Dubai, compared with ten in 2022.

Toya says that, in addition to the financial burden of a trip that costs roughly $5,000 per person—“we have to look for several partners”—the Indigenous attendees face the linguistic barrier. Most of them are bilingual, if not multilingual, but neither Portuguese nor the languages of Brazil’s original peoples are official at the UN.

Still, Toya feels it is worth going. “It’s interesting for us because we’ll have more information when the Brazilian government starts implementing things here,” he said. The financing debate interests Toya, as does the carbon market, a source of forest conservation funds for both businesses and governments.

One of the problems is that money earmarked for confronting climate change takes a long time to reach communities, or never gets there. Toya cited the example of a $1.7 billion fund for forest peoples announced at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2021. The first year, only 7% of the $331 million that were disbursed reached Indigenous and community associations directly.

Another case in point is the project meant to direct funds to Amazon region governments as payment for avoided deforestation in their states; the money would come from the LEAF Coalition, another mechanism launched in Glasgow. Indigenous people want to have a say in how the money is spent. “Not that we’re going to stop doing what we already do, because Indigenous lands are our home. But if there are resources to strengthen our organization, our social system, and the economy within the community, it would be much better,” Toya said.

Initiatives like the LEAF Coalition are common at COPs, where many parallel events are held alongside negotiations. Groups of countries launch a variety of “commitments.” In Glasgow, for example, 105 countries, including Bolsonaro’s Brazil, promised to end deforestation by 2030. This year the Brazilian government and some 80 other countries with tropical rainforests are due to release a joint declaration. These pledges make headlines and have political repercussions but, unlike official COP documents, they don’t have the force of international law.

Despite her critical view of the conference, the journalist Mariana Belmont says that every year more people from the Black movement have organized to participate and try to influence negotiations. “The documents talk about poor people, people in situations of vulnerability, but they don’t say who these people are. They are women, youth, Indigenous people, Afro-descendants,” she said. “When negotiations get real close to human rights, they stop, but civil society, all over the world, has been pushing to change that.”

It’s a little bit like the tactic of slow but steady wins the race, yet patience is running out. “Sometimes people feel like it’s not going to work very well in the end. Several days are spent negotiating a decision, but implementation ends up postponed until the next COP. Meanwhile, people are dying; they don’t have time [to wait],” said Mariana.

Our coverage in Dubai is in partnership with Global Witness (@global_witness), an international NGO that has been investigating, exposing, and campaigning against environmental and human rights abuses around the world since 1993

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Layout and finishing: Érica Saboya

Editorial workflow and copy editing: Viviane Zandonadi

Director: Eliane Brum

Cries and whispers: demonstration by Extinction Rebellion during the COP conference in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2021. Decisions made behind closed doors disappoint. Photo: Pierre Larrieu/AFP