You may not feel it yet, but the world’s climate is in the midst of a jolt so far away from the norm that some scientists are looking at the data with a mix of disbelief and horror. Other meteorologists warn this is what we must expect now we have entered into another period of El Niño, the irregular climate phenomenon that boosts global warming for a period of several months or several years. The question for those of us who live in the Amazon – or depend on its rainfall regulating function – is how will the forest respond in the coming fire season?

The latest climate jolt was initially evident in uninhabited or sparsely inhabited places: the stratosphere, the Antarctic and the surface of the Atlantic Ocean. Since May, measurements of temperature or ice in these locations started to meander off the usual track in a disturbing fashion.

It is not just that the climate is warming or the ice is thinning. We have known that for a long time. It is now etched into our baseline expectations of the global climate. Sadly, the new normal is that the world is steadily getting hotter and more unstable.

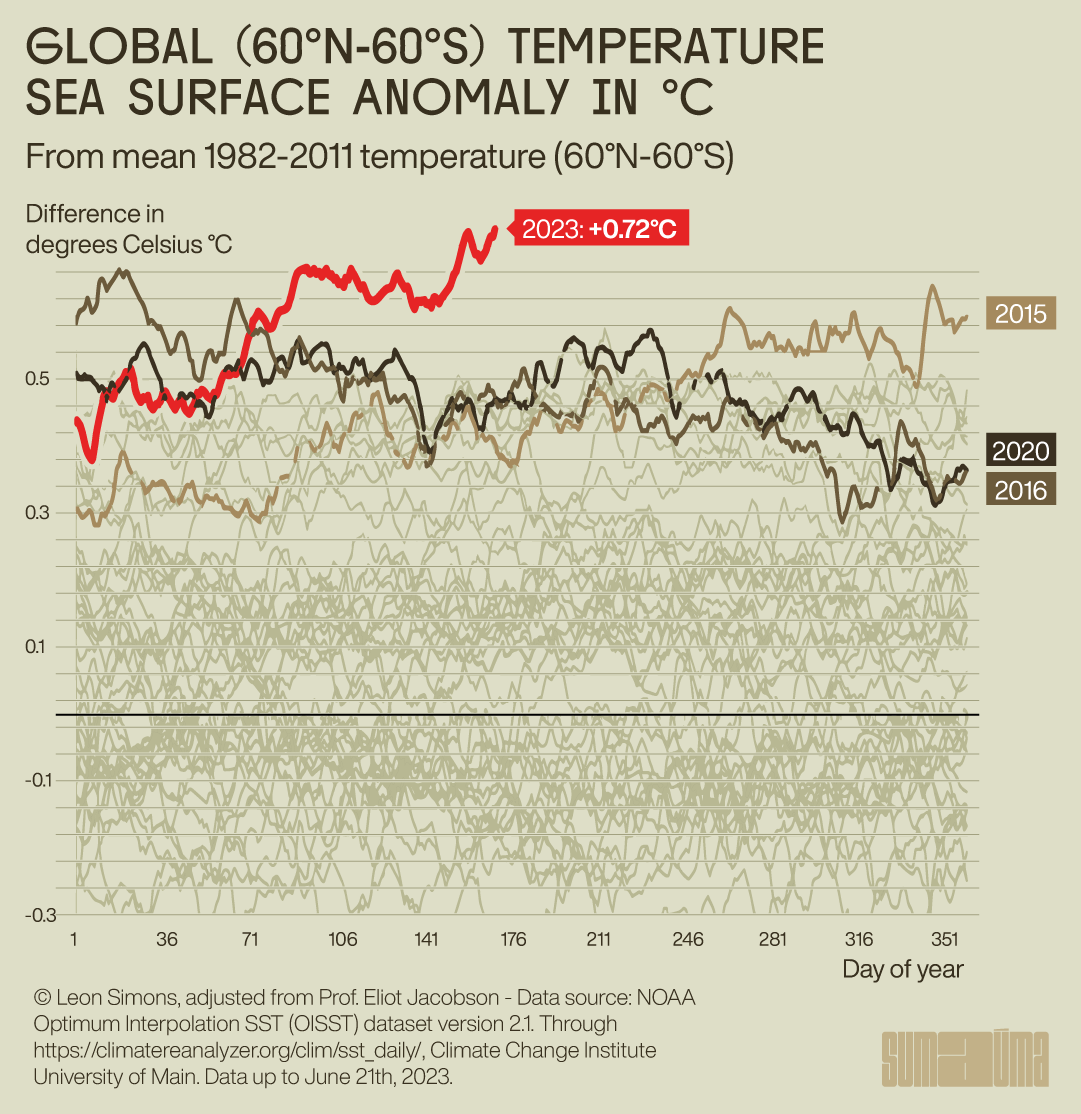

But the latest disruption was anything but steady. It took a different shape. The graphs looked as if someone had bumped into the measuring instruments and jerked the printer tip up towards the top of the page, like a bumped stylus scratching across a vinyl record.

Sea temperatures and ice-extent measurements usually form a gentle arc that stacks higher year after year according to the season and increasing upward pressure from human emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. But in May and June 2023, they seemed to lose their sense of direction and zag abruptly upwards into strange new territory.

I’ve been looking at climate graphs for more than a decade and I have never seen anything like this. I reassured myself that I am a journalist not a scientist so maybe I am over-interpreting, maybe this is not as unusual as it looks. So I checked on the Twitter accounts of scientists I follow.

Here we go again, a new record anomaly for North Atlantic sea surface temperatures.

Today’s anomaly is a full 1.15°C above the 1982-2023 mean for the day. I thought the previous peak was high, but I may need to extend the y-axis again soon!

Data: https://t.co/RxO8s5Y85O pic.twitter.com/J1eIMhuOHG

— Prof. Eliot Jacobson (@EliotJacobson) June 21, 2023

This is getting to be utterly unbelievable… the North Atlantic SSTs have just set a new record anomaly on June 20, beating the previous one from June 10. At an average temperature of 23.24°C, that’s 1.11°C above the 1991-2020 mean, or +3.87 standard deviations. 1-in-18,650. pic.twitter.com/N2OhZwaoMc

— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) June 21, 2023

US climatologist Brian McNoldy calculated that North Atlantic surface temperatures were so far above average on 10 June that it was “totally bonkers” and “people who look at this stuff routinely can’t believe their eyes. Something very weird is happening.” He calculated there was “a one in 256,0000 chance of observing what we are observing. This is beyond extraordinary”. Any hopes that this was a blip faded in the days that followed. The freak ocean heat

grew worse. McNoldy said the results questioned the very science of using past data to estimate the probability of extreme weather events.

Other, more influential, climate scientists such as Michael Mann and Zeke Hausfather say there is no need to panic because these sharp short-term increases can be explained by the shift from a La Niña cooling phase in the Pacific to a warmer El Niño, which generally brings hotter weather to large parts of the world. This relieves some of the mystery about the strange shape of the graphs, but it is not reassuring. They are confirming that an already bad situation is about to get worse because of El Niño. It will amplify global heating trends, which probably means more intense droughts and storms, and more widespread destruction and suffering.

Large scale fire in the municipality of Apuí, Amazonas. Photo: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real

Increase of extreme events

In many parts of the world recently, humanity has started to feel the effects of this initial El Niño jolt. Last month, the smoke from historic forest fires in Canada choked New York City. In Mexico in recent weeks, several cities have repeatedly broken the record for their hottest days ever, including Chihuahua, Nuevo Laredo and Monclova. Puerto Rica and many cities in Texas have suffered their worst-ever heat waves. The same is true in China, where more than twenty cities, including Shandong, Tianjin and Huairou have registered new peak temperatures. In Europe, the Austrian town of Oberndorf sweltered in a freakishly hot midnight temperature of 36.1C, one of the continent’s highest ever nighttime temperatures. In the Middle East, people are used to heat but they can normally expect some respite at high altitudes. That was not the case this week, when the Iranian town of Saravan experienced 45C – one of the hottest days ever recorded in the world at an elevation of more than 1,000m.

Storms are forming in the Atlantic earlier than normal as a result of the extra energy that is building up in the surface layer of the ocean. For the first time in June, there are now two simultaneous tropical storms in the Atlantic, Bret and Cindy. Making matters worse, there are also longer-term signs that global climate drivers – the water gyres in the ocean and the air currents in the atmosphere – are slowing down, which means weather systems get stuck. This causes heatwaves and storms to linger longer, causing more damage.

So, what does this have to do with the Amazon? Scientists have shown that the rainforest suffered unusually severe warming and droughts during the previous two major El Niño events (2014 to 2016 and 1997 to1998). The impact varied by region: In 2015, the heavily deforested Eastern Amazon was worst affected by drying, while the healthier forest in the Western Amazon had more rain. There is a strong risk this may be the case again. But this time, the forest is much weaker. Since 2015, many areas have suffered deforestation and degradation, which lessens the resilience of the ecosystem to fire and drought. Forest protection agencies have also been run down and many land owners and land grabbers have come to believe they will enjoy impunity if they clear forest with fire.

This is a vitally important moment. We must recognise that we are in an emergency within an emergency. All impacts will be amplified. The El Niño has just started. Past trends suggest it will grow more intense in the months and possibly years ahead. We don’t know yet how bad it will get or how long it will last but the early signs have been awful. If this proves a severe, protracted El Niño, then past experience suggests we could see an Amazon calamity on a scale never seen before.

What can be done? There is still uncertainty, but precautions make sense. Forest dwellers and local governments should prepare for severe drought and strengthen their fire response capacity. The central government needs to rapidly strengthen forest protection laws, enforcement agencies and punishments for those who cause fires. Even the agriculture-industry-dominated Congress needs to recognise the greater-than-usual risks now facing the forest, which is the main climate regulator in the region and the best bulwark against El Niño-type impacts. Without a strong Amazon, the risks of a drought elsewhere in Brazil will increase. The quicker everyone realises we face an exceptional risk the more likely we are to maintain a recognisable climate. This jolt must not just disrupt, it must energise.

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

Portuguese translation: Denise Bobadilha

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

Page setup: Viviane Zandonadi