The historic occasion when Kayapó chief Raoni Metuktire ascended the ramp of the Palácio do Planalto, Brazil’s seat of government, on January 1 this year brought hope to the Indigenous peoples of Brazil and their supporters: the relentless actions against Brazil’s original peoples by Jair Bolsonaro’s government, which would culminate in accusations of genocide, was over. For Dr Deise Alves Francisco, the symbolism of Raoni’s presence at the inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, better known as Lula, as Brazil’s president for the third time, was the catalyst for another sequence of emotions. In 1989, when Sting brought Raoni to the stages of Europe, the US and Japan to defend Indigenous rights, Deise, then a recent graduate, made a decision that would alter her life and career. “It was the end of the 1980s and I was in Spain, (traveling) between Madrid and Barcelona. My plan had been to do a post-graduate specialization course in acupuncture. When I saw Raoni, I told myself I had to go back to Brazil and work in Indigenous health. And so I did.” Cláudio Esteves de Oliveira, also a doctor, had discovered his vocation years earlier, when he took a trip to the northeast of Brazil with a copy of “Quarup”, a classic of Brazilian literature by Antonio Callado, in his luggage. After giving up a career as an engineer, and having passed the application process for a job in the Rio de Janeiro customs office, literature led him down an unusual path. “I really liked to travel, I was a backpacker, and when I read “Quarup” I got the idea that I wanted to get to know Indigenous people,” he says. “And the way to do that was to study medicine, which would be useful for them at that time. I would become a doctor and work with Indigenous people. And that’s why I studied medicine.”

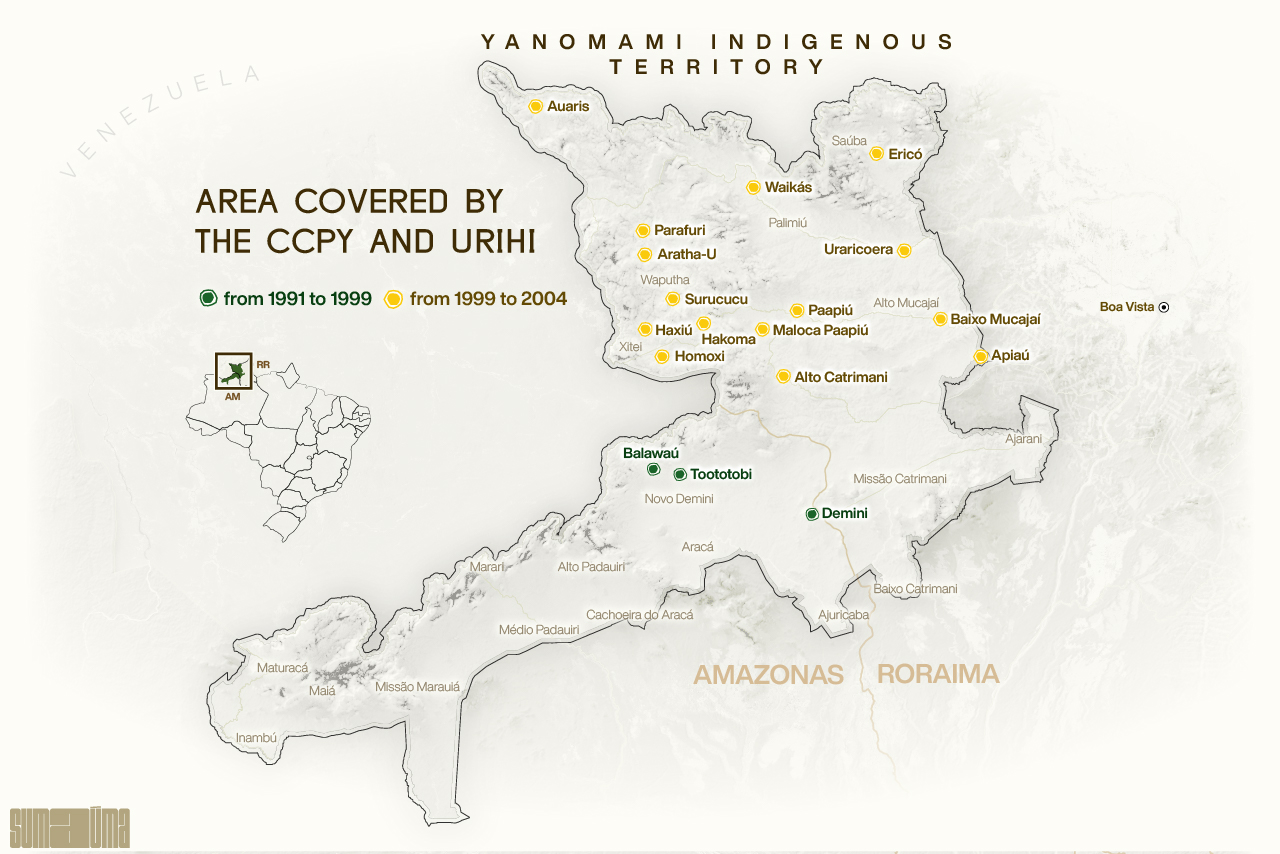

No conversation about Indigenous health in Brazil would be complete without mentioning Deise and Cláudio. Or rather, without the mention of the healthcare projects established in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, initially by the Comissão Pró-Yanomami (the Pro-Yanomami Commission, or CCPY), and later by Urihi-Saúde Yanomami (Urihi Yanomami Health, in English), in the 1990s and 2000s. In recent discussions between Indigenous leaders and the National Security Force of the Brazilian public health service, known as SUS, which has been performing emergency operations to prevent the Yanomami genocide, brought about by the advance of illegal mining encouraged by Bolsonaro, the words “we need to bring the Urihi model back to the villages” were frequently heard. For the Yanomami, Urihi is the forest, and the period when the NGO existed is invoked using an almost mythical symbology, of a time when there were no diseases and no evil, and when everything was good.

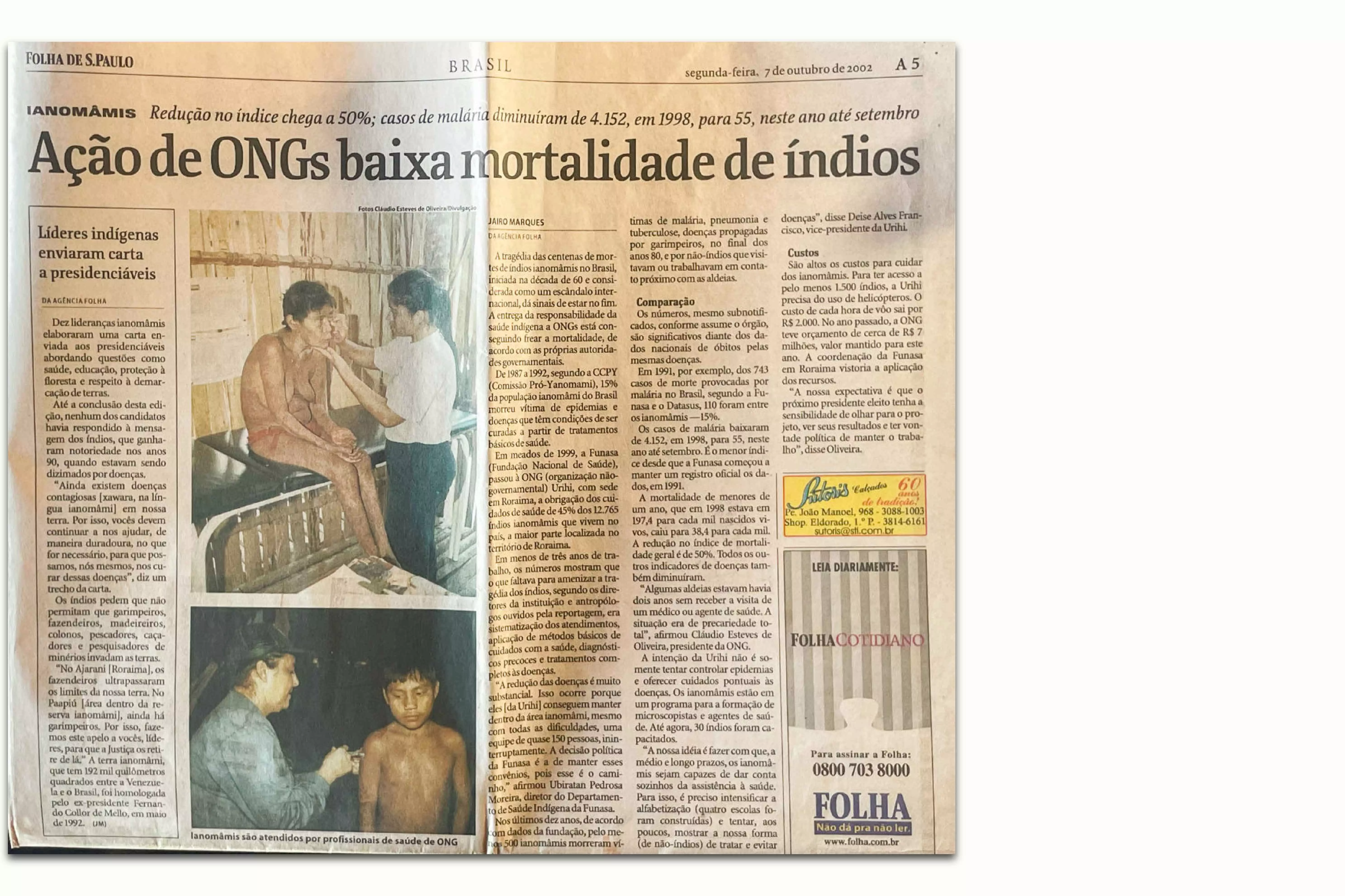

The Urihi-Saúde Yanomami NGO was created in 1999 to expand the effective, revolutionary care model in the region. Initiated by the CCPY, the model reduced deaths from malaria to zero, brought an end to infant mortality, and ensured the Yanomami population would grow once more, preventing the extermination of this people, who have existed for thousands of years, in the 1990s.

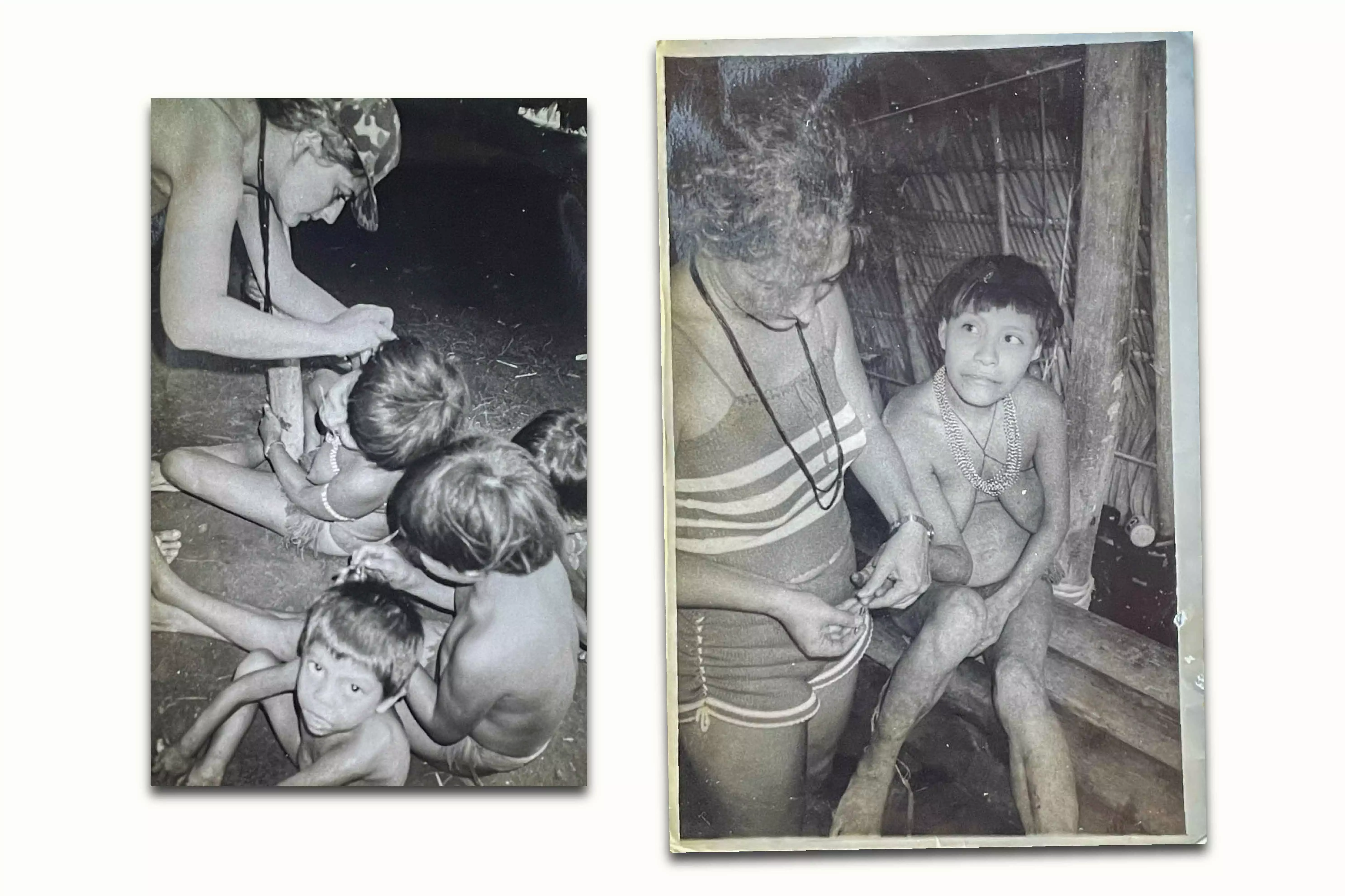

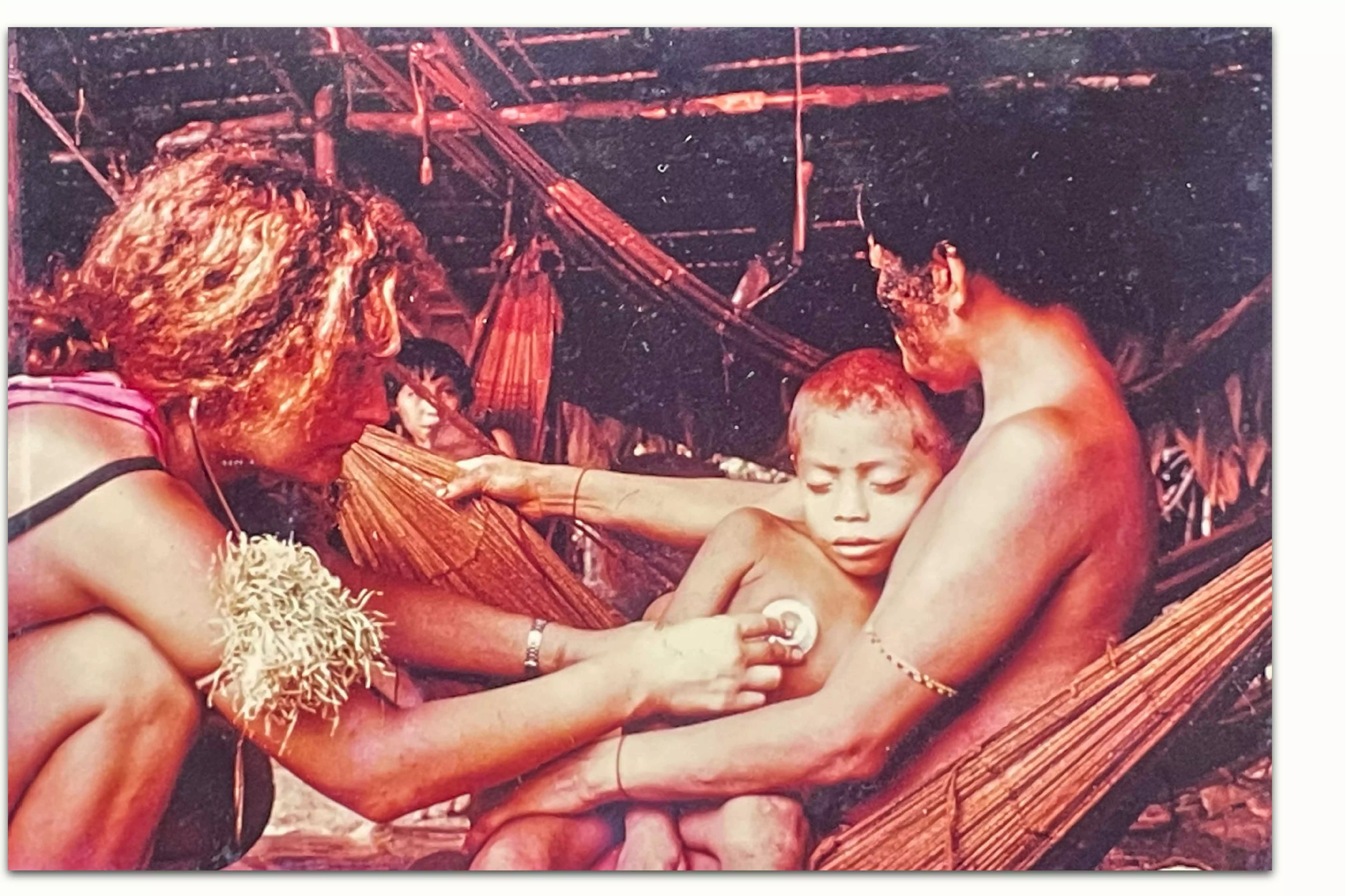

DEISE ALVES AT WORK IN BALAWAÚ: (L) PROVIDING MEDICAL CARE TO CHILDREN IN 1991; (R) COLLECTING BLOOD FROM A YANOMAMI WOMAN TO TEST FOR MALARIA IN 1992. PHOTOS: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/AUTHOR UNKNOWN. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

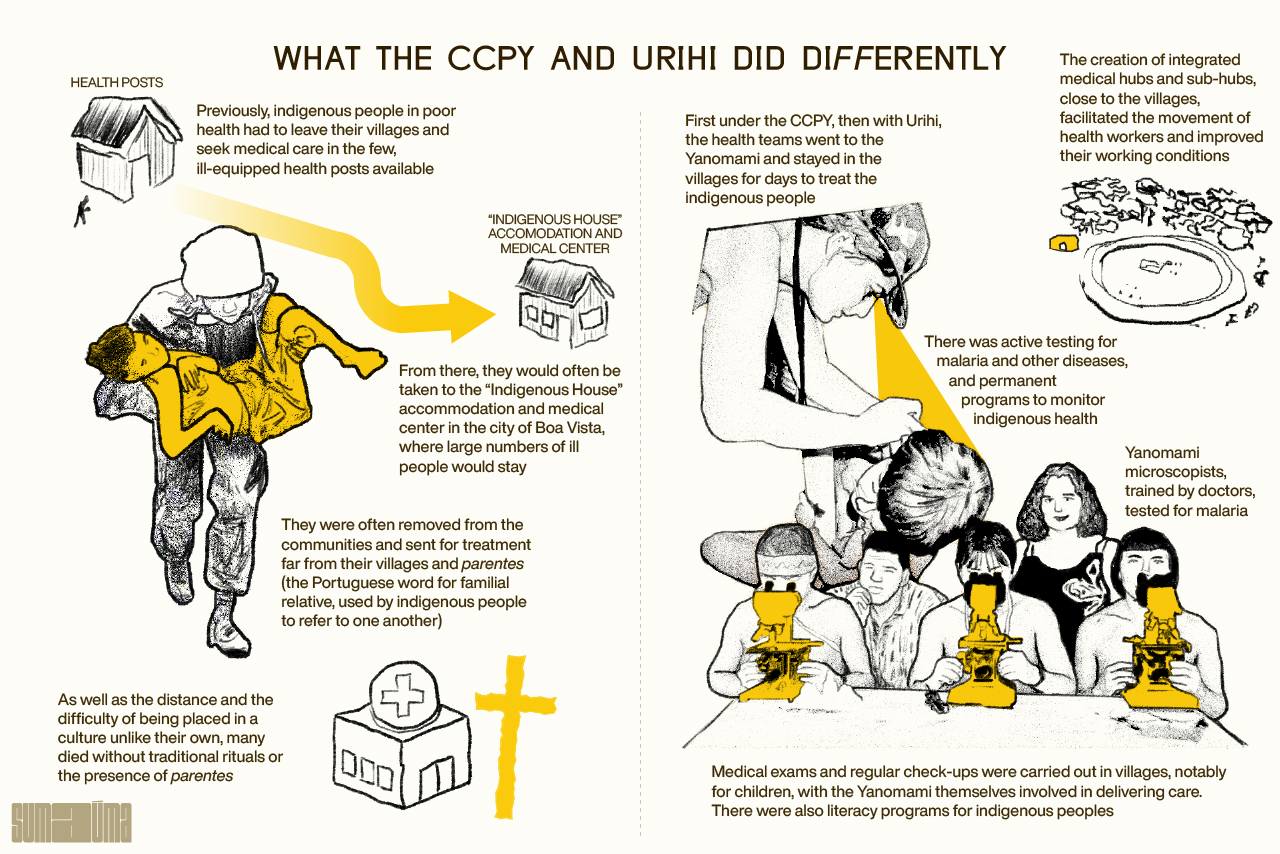

“It was a Copernican revolution,” renowned French anthropologist Bruce Albert, who worked with the doctors on both projects, says of the work the pair oversaw with Urihi, when they were responsible for the healthcare of 50% of the Indigenous villages in the Yanomami Territory. The reference to Copernicus, who showed that the earth and the planets revolved around the sun, rather than the other way around, is apt: in the almost 15 years Deise and Cláudio spent with the Yanomami in their lands, they proved that health professionals should travel to the villages to treat Indigenous people, not the other way around.

Significantly, the Yanomami themselves recognised this healthcare revolution in the 1990s and early 2000s and appreciated its innovative, autonomous, respectful and ethical model. But this did not spare Cláudio and Deise from a Kafkaesque fate, in which they became the victims of a legal case that mixed absurdity and surrealism, reality and fiction, and undermined the 15 years they dedicated to the Yanomami, robbing them of the chance of working as indigenist doctors and practicing their chosen profession.

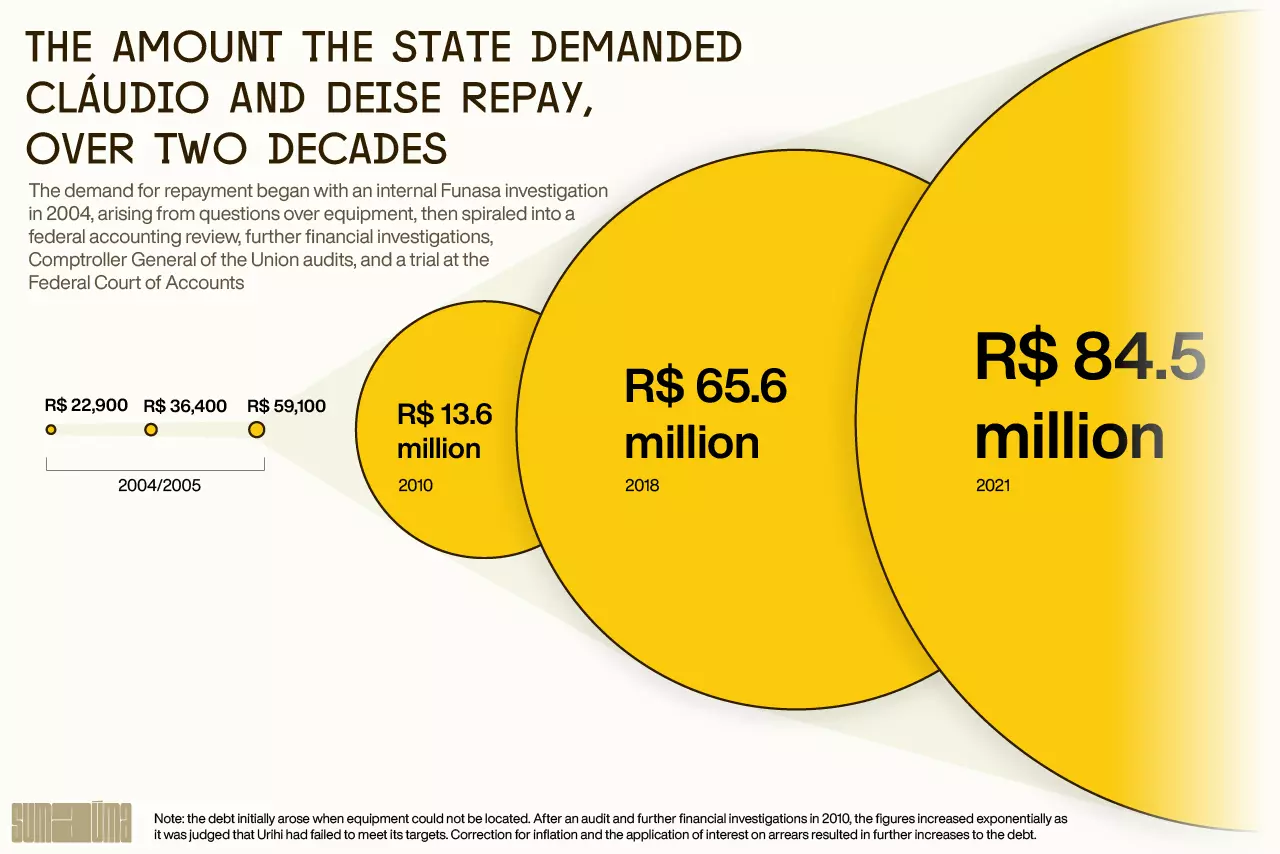

In October 2018, Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts, which audits the spending of public bodies, ordered Cláudio Esteves, as the president of Urihi, to repay funds to the country’s treasury, or in other words, to reimburse the federal government for the use of public resources. More than ten years after the end of Urihi and the medical services contract under which it operated in 2004, the court ordered Cláudio and the NGO to repay the money that had been provided to the organization by Brazil’s then National Health Foundation, or Funasa, to deliver healthcare to the Yanomami. The verdict ruled only against Cláudio and Urihi. All the former directors and presidents of Funasa were absolved by the Federal Court of Accounts.

In March last year, Cláudio Esteves received a call from his mother’s caregiver (who has since died), telling him that a financial demand in his name, sent by the First Regional Federal Court of the state of Roraima, had arrived at his mother’s house. He asked the woman to send him a photograph of the letter, as he had returned to Brazil just a few months before and was trying to start over, once again, this time in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. The contents of the letter left him stunned: he had five days to repay a debt of 84,557,766.49 reais (U$16,587,109.43), failing which he should provide a list of his assets to be seized. But Claudio doesn’t have any assets, apart from a 2021 Renault Kwid which he is still paying off. The debt in the millions he owed to the Brazilian state had been officially generated at the end of December 2019. A few days earlier the sum had been recorded as an executable federal debt.

But this is not simply a legal process (or rather, a collection of legal processes and administrative procedures over a 19-year period). Like Josef K. from Kafka’s “The Trial”, the doctors who created Urihi do not understand the reasons for the conviction, much less accept it. They were unable to defend themselves, were not given access to their files, and did not recognize many of the documents on which the case against them was built. They were stunned by the enormous amount owing, which neither of them considers a legitimate debt to the Brazilian state. During the course of a long administrative and legal journey, which passed through Funasa’s internal audits, financial investigations, federal accounting reviews, a declaration of default, an examination of the technical and financial reports of the medical services contracts, a Federal Court of Accounts audit and even a quasi-criminal case, Urihi’s alleged debt with the state leapt from 22,900 reais (around $4,500) to more than 84 million reais ($16.6 million). In the first years of their legal battle, Cláudio and Deise filed responses to each query raised by Funasa in relation to every aspect of Urihi’s medical service contracts and the materials it had acquired. They also provided a formal response to the Federal Accounts Court in August 2006, detailing the work of Urihi and the unique characteristics of providing Indigenous healthcare in the vast Yanomami territory. They had to defend themselves in the second parliamentary enquiry into NGOs in the Brazilian Senate in 2007 (the first was in 2001), after the media claimed Urihi was responsible for misappropriating millions of reais in Indigenous health funding, without any investigation of the work that had been carried out in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory. Cláudio and Deise were condemned and punished by the press first of all – most of the time without the right to a defense.

Without legal aid resources and with their careers tarnished, the pair say the following years left them drained. They moved from the north to the south of Brazil, as though distance from the Indigenous regions could alleviate their suffering. Exhausted and with few professional opportunities on the horizon, they sought a new life outside Brazil, where they would remain for almost a decade. But they never left the story of Urihi behind. Today, the two regret their naivety in refusing to believe the case against them would go ahead, as everything they had done in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory had been properly documented. And they feel a deep hurt. “Yes, I regret my naivety every day. When we saw that nobody would help us (in the defense of the case), that we would have to use our own money (to pay for a lawyer), I thought it was ridiculous… It was the state that invited us to sign the medical services contract (1999). We’ve always lived off our wages. It was money (for day to day expenses) for my daughters. We never imagined that no one would defend us. No one.”

Nineteen years after the end of Urihi, Cláudio and Deise have decided to tell, for the first time and exclusively to SUMAÚMA, the story of how their lives were destroyed, despite their work. The two believe what happened to Urihi to be a reflection of an economic scheme that, for decades, has been trying to occupy the Yanomami Indigenous Territory and destroy the Indigenous people, to allow the unfettered exploitation of gold and cassiterite. The creators of Urihi and activists working on behalf of the Yanomami who met the doctors and are aware of the projects they coordinated also believe there was political persecution of the NGO, as over the years it had denounced local pro-mining political interests. It also criticized the new Indigenous healthcare model that began to be trialed from 2004 onwards, warning of the risks to Yanomami health: financial irregularities and misappropriations, and potential corruption, which later proved to be true.

“This is the first chance we’ve had to talk about our experience, after everything that happened. It is our first moment of reconciliation with the whole story, which had an enormous impact on our careers, our professional and our personal lives. Being able to speak now is like being rescued,” says Deise, venting frustrations pent up for over a decade.

DEISE AND CLÁUDIO RECALL WORKING IN THE YANOMAMI INDIGENOUS TERRITORY. ‘BEING ABLE TO SPEAK NOW IS LIKE BEING RESCUED,’ SAYS DEISE, VENTING FRUSTRATIONS PENT UP FOR OVER A DECADE. PHOTO: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

Urihi’s case is emblematic – and not just for its historical significance and an understanding of the challenges and specificities of Indigenous healthcare, especially in the Yanomami region, an area of almost 9.7 million hectares that crosses the states of Roraima and Amazonas in the north of Brazil, and is the size of Portugal, and considerably larger than countries such as Switzerland and Belgium. The final verdict against Urihi is a catalog of intertwining Brazilian ills: it exposes the nefarious side of political divisions in coalition presidentialism, ideological errors over the role and action of the Brazilian state, the cyclical violation of the rights of native peoples, the policy of greed that destroys the forest and life itself, the ineffectiveness and sluggishness of government bureaucracy, the slow pace of the judiciary, the carelessness and irresponsible nature of the press, the often erroneous analyzes made by supervisory agencies, the difficult and delicate balance between the voluntary sector and politics, the obstacles to accessing justice in Brazil and, finally, the ease with which reputations and lives can be destroyed.

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, the most influential leader of his people, has for decades been trying to explain to the napëpë (non-Indigenous people) the meaning of Hutukara, the universe-world, and Urihi, the forest-land. A witness of the work of Urihi-Saúde Yanomami, he spoke to SUMAÚMA by telephone about this “very long history” that guaranteed the survival of his parentes (a term used by Indigenous people to refer to one another) and halted the advance of mining. The government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, he says, thought the work of the CCPY in the area was “beautiful” and offered funding “to take care of the Yanomami”. Davi stresses the money was for his people – “under my responsibility”. He recalls how at that time, the National Health Foundation spent rivers of money on Indigenous health, but did so inefficiently. “They couldn’t heal us and just brought the Yanomami to die here in the city. I didn’t like it. But Urihi Saúde provided treatment there in the community, in the Yanomami Territory. That’s how Urihi Saúde worked.” The work of the NGO, Davi testifies, was organized and effective, and brought an end to malaria and other diseases, using low levels of public resources in an efficient manner, with health workers “who liked the Yanomami people.” The shaman adds another point. “Dr Cláudio and Dr Deise were already working with the CCPY,” he says. “They coordinated (Urihi), they took on the responsibility. They aren’t politicians. That couple isn’t political. Isn’t that right? That’s why the health was good, to save the Yanomami people.” “Save” is a recurring word in the shaman’s recollections. “This is how Urihi Saude-Yanomami saved my Yanomami people, my little children, my children, from the Amazon and from Roraima. I’m trying to bring it back. But it’s hard. Public health doesn’t want to help. What we want is for Yanomami health to improve this year.”

“Urihi saved the Yanomami people,” agrees Junior Hekurari, current president of the Urihi Yanomami Association. Fourteen years ago, he learnt to read and write through Urihi Saúde-Yanomami. The village elders, Junior told SUMAÚMA, remember such days, and want health professionals like Deise and Cláudio to “save” the Yanomami people once again. As a teenager, he helped guide health teams from the old Urihi in the Surucucu region, in the uplands of the Yanomami lands, an area which is extremely difficult to access. Thanks to the Urihi project, Junior Hekurari has become an important figure in the new generation of Yanomami leaders, and played a key role in alerting the world to the Yanomami genocide under the Bolsonaro government. The association he created now bears the same name as the old Urihi organization, but because of the sacred meaning of the word, rather than the NGO. “Who is living in Urihi? The Yanomami people. Who defends Urihi? The Yanomami people. Who brings our resources? Urihi. That’s why we gave the name to our association in October 2022. Urihi is the forest, in the Yanomami language. So that Urihi won’t die, we used that name.”

“Copernican Revolution”: the origins of Urihi

When the young Deise returned to Brazil in 1989, Funai, the country’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs (then known as the National Foundation for the Indian, today renamed the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples), organized mobile health teams to provide emergency care in the Yanomami area. The Pro-Yanomami Commission, or the CCPY, one of the organizations that partnered with Funai, had been created in 1978, in defense of the territorial, cultural and civil rights of the Indigenous people, by the photographer Claudia Andujar, the anthropologist Bruce Albert, the Catholic missionary Carlo Zacquini and others who would become global figureheads in the struggle for the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory. Now 85, Carlo has been in contact with the Yanomami people since the 1960s, and accompanied Andujar on numerous missions to the territory inhabited by a people hitherto unknown to the non-Indigenous world. Since the beginning of the 1980s, Davi Kopenawa Yanomami had been working with the CCPY on projects that were fundamental to ensure the demarcation of the area, as well as in the implementation of a bilingual education project for Indigenous people, which, crucially, would allow the Yanomami themselves, years later, to denounce the continuous violation of rights in their territory by non-Indigenous people. The shaman’s help would also be fundamental in the operation of Urihi Saúde.

In 1991, for the first time outside Brazil, Davi Kopenawa spoke to the UN Inter-American Commission on Human Rights about the genocide of Indigenous peoples, brought about by the advance of illegal mining and disease. Even after the demarcation and ratification of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, in 1992, by Brazil’s then president Fernando Collor, the CCPY’s arduous struggle continued. “I was one of those contracted by the CCPY (in partnership with Funai),” recalls Deise. “I made two trips of a month, then two months, in which I stayed in the area. And the second time I came to the conclusion that there needed to be a more permanent healthcare solution in the Yanomami territory, because one-off mobile teams wouldn’t solve the problem. At the same time, the demarcation debate was taking place in 1991, 1992.”

DEISE ALVES AND MARCOS TEODORO DO CARMO, MICROSCOPIST AND INSTRUCTOR ON THE FIRST TRAINING COURSE FOR YANOMAMI MICROSCOPISTS, OBSERVE STUDENTS JOSECA, GÉRSON AND GERALDO, AT THE YANO HEALTH POST, IN THE BALAWAÚ REGION, IN 1995. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

In the early 1990s the situation in the region was tense. “Operação Selva Livre” (Operation Free Forest, in English), organized by Brazil’s Federal Police, Funai and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to remove illegal miners from the Yanomami Territory, had begun surveillance operations. Reports suggested 40,000 such miners had invaded the region, and there was strong international pressure to remove them, especially following the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. In 1993, at the height of the removal operation, came the horrifying news of the Haximu Massacre, when twelve Indigenous people – adults, teenagers, children and a baby – were killed by miners with guns and machetes. In the files of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, the events leading up to the killings are described as follows: “The conflict began when miners operating illegally in the region failed to fulfill promises they had made to Indigenous people in the area. On June 15, seven miners invited six Indigenous people to go hunting and, on the expedition, killed four of them. In retaliation, the Indigenous people murdered one of the miners. That was the trigger for the massacre that would take place days later.” In total, 16 Indigenous people were killed.

It was in the midst of this climate of tension that Deise and Cláudio moved to the state of Roraima. They met at work and, shortly after, fell in love and started a family. “I went to live in Roraima at the beginning of the removal of the miners. Then I proposed a permanent healthcare project to the CCPY, whose work at the time covered an area that was home to 10% of the Yanomami population,” explains Deise. From 1991 onwards, she was responsible for organizing the CCPY’s Indigenous health program, which relied on international funding, notably from Survival International. “It’s worth remembering that, at that time, the Ministry of Justice announced the area would be demarcated and ratified, and months later Bolsonaro (then a member of the Brazilian Congress) launched a draft legislative decree to revoke the demarcation ruling. This is a longtime personal project of his, to open up the area for mining,” she adds. Bolsonaro’s Draft Legislative Decree 365 was presented to the Brazilian Congress in September 1993 to “annul the Decree dated May 25, 1992, which ratifies the administrative demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in the states of Roraima and Amazonas.” The proposal was archived and recalled numerous times. In 2003, Bolsonaro tried to revive it again, before it was archived for good in 2007.

Cláudio arrived in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in 1991, shortly after Deise. Having obtained a medical degree, he had opted for a residency in clinical medicine at Rio de Janeiro Federal University. Dr Stella Lobo, who coordinated the residency, had been invited by the National Health Foundation (the Fundação Nacional de Saúde, or FNS) to carry out a field trip in the region. Aware of Cláudio’s interest in the Indigenous people, she invited the young doctor to join her team. Part of their work would result in the creation of the Yanomami Health District, inspiring the model of the Special Indigenous Health Districts which still exists today. There are 34 such districts in Brazil, with the Yanomami unit the first to be established.

On his first trip to the area, Cláudio would stay in the Auaris region for two months, accompanying a microscopist to detect cases of malaria. “We found a very similar situation to that which we’re seeing today. A high percentage of malaria, terribly debilitated Indigenous people who are unable to fight to survive, to hunt, fish or work in their plantations. And hunger. Two, three months in this situation, and they became skin and bones, just going back and forth, from the mines to ask for food, to the old health posts, which were still very basic, to ask for medicine. They walked along the trails, and we encountered row upon row of Yanomami people.” One day an Indigenous man who had walked more than ten hours from Tukuxim arrived at the health post where Cláudio was, begging for help for his parentes. “I don’t know how he got there alive. We got a Brazilian Air Force helicopter, which dropped us off on a runway that had been blown to bits. We found more than 300 Indigenous people there in a severe state of malaria and malnutrition.”

This trip was a turning point in Cláudio’s life. On the date the team were scheduled to go back, the air force pilot did not show up to rescue them. “They just left us there. There was no radio communication at all at that time, and we stayed 11 days after the allotted time. Our food ran out the day after they were supposed to come get us, and the Indigenous people had practically no food either. We spent ten days eating almost nothing, just what they gave us. We treated them all. One happy day we heard the noise of the helicopter and we ran out, because they were going to land and we weren’t on the runway waiting. I lost 11 kilos. I got malaria afterwards.” The moment was so transformative and defining of his career that, shortly afterwards, certain of his choice, Cláudio became medical director of the Casa do Índio (“the Indigenous House”, a healthcare and accommodation center) in Boa Vista. Like Deise, he was convinced an effective healthcare policy needed to provide permanent care to Indigenous people in their collective homes. It would be impossible to eradicate malaria whilst far from the villages. That was when the CCPY invited him to be a field doctor, in the project coordinated by Deise. Dissatisfied with the structure and vision of the FNS, he agreed to join the project. “After that, I got malaria about ten times,” jokes the doctor, who is now retired.

The first phase : 1990 to 1994

In the first years of the Indigenous healthcare project designed and coordinated by Deise, the CCPY looked after three areas – Toototobi, Demini and Balawaú – which accounted for 10% of the Yanomami territory, with teams working permanently in the villages. There was some resistance to the model within the indigenist movement, which feared the Indigenous people near the health service areas could become sedentary, as well as undue interference in their culture, which never occurred. There was a fear that “contact would change their culture and this would be bad for them,” explains Deise. This argument was defeated within the CCPY and Urihi thanks to the attentive anthropological vision of Bruce Albert. The main idea behind the project was to create small service infrastructures, but scattered throughout the area, with base and sub-hubs.

CLÁUDIO ESTEVES PROVIDES CARE TO THE YANOMAMI OF THE TUKUXIM REGION, IN 1991. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

The system was based on the logic of a decentralized service. From the base hubs, the health team would travel to the Yanomami – and not the other way around. “This was the great methodological contribution of our experience at the CCPY, which was later expanded with Urihi. The problem with previous permanent care was that it was fixed at one point and the Indigenous people had to go to the health post. Our idea was that it (the post) was just a reference point around which to organize the teams, who would travel to the malocas (Indigenous dwellings),” says Deise.

The CCPY project required teams to actively search for cases of malaria in each community. In addition, there were permanent programs for women and children’s health, prenatal care, vaccinations, weighing and oral healthcare, with regular scheduled visits. The teams needed to meet care targets. “We introduced social controls (carried out by the Yanomami themselves), because if a health worker stopped going to the malocas, we would hear the complaints from the Indigenous people. We always checked with them that the teams were actually visiting regularly. We brought everything, including microscopes, to diagnose malaria in the malocas,” recalls Cláudio.

“It seems obvious, but it was seen as a myth that you could treat the Yanomami in the middle of the Amazon rainforest, with their own health system. It was all something very new, but which later proved to be accessible,” says Deise. The results were spectacular, with marked differences between the epidemiological indicators of the three areas that the CCPY attended to and the rest of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory. “At the time we looked after 10% of the territory. The FNS took care of the other 90%, and it was a total failure: there was no plan, no method being followed, no nothing, there was no common program for the area, and no staff. Because what has always been the big question mark for the issue of the Yanomami Health District, and for all Indigenous health, is the issue of human resources. (The FNS) were occasional collaborators the entire time,” says Deise. The secret (of providing good healthcare in a challenging area) was to ensure good working conditions for healthcare staff to keep the system working, explains the model’s creator. “The CCPY had good results, permanent care, and a fixed staff with labor rights. The FNS had 120 public workers and 90 temporary workers. And they only had 30 people working in the area. This whole precarious structure led to a failure of execution on the part of the FNS (which would later be renamed Funasa).”

DEISE ALVES CARES FOR A YANOMAMI CHILD IN THE BALAWAÚ REGION. IN 1993. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

The second phase: the start of federal funding (1994-1999)

In addition to the pressure caused by poor health indicators in most of the Indigenous area, there was also the Brazilian government’s commitment to eradicate onchocerciasis, which it had announced on the international stage. “The Yanomami territory is the only place in Brazil with the disease called onchocerciasis, known in Africa as river blindness, which in fact arrived with the slaves. Nodules, which are the adult worms, form on the skin and procreate, and the non-adult worms migrate through the skin, causing itching, and eventually reaching the eyes, the cornea and the retina, and causing blindness. In the Yanomami territory there were no cases of blindness from onchocerciasis, but Brazil is one of the few countries in the Americas with the disease,” explains Cláudio.

(L) CLÁUDIO HELPS A YANOMAMI CHILD IN THE SIAPA RIVER REGION IN VENEZUELA, IN 1998. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. (R) DEISE BETWEEN JOURNALIST JAN ROCHA, THE YANOMAMI LEADER TOTO AND THE ANTHROPOLOGIST BRUCE ALBERT AT THE CCPY ANNUAL ASSEMBLY THAT GAVE RISE TO THE EDUCATION PROGRAM AND THE TRAINING COURSE IN MALARIA DIAGNOSIS FOR YANOMAMI MICROSCOPISTS, IN THE TOTO COMMUNITY, TOOTOTOBI REGION, 1994. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/CLAUDIA ANDUJAR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALC NTARA/SUMAÚMA

Faced with such a problem, and with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) watching on, expecting the eradication of the disease, the FNS approached the CCPY and suggested a partnership. “They proposed that we deliver the (Indigenous health) project with them, that our medical services contract be exclusively with the Brazilian government itself and that instead of having our own resources for the project, that we do it with federal funding,” explains Deise. “And that’s how we operated until 1999.”

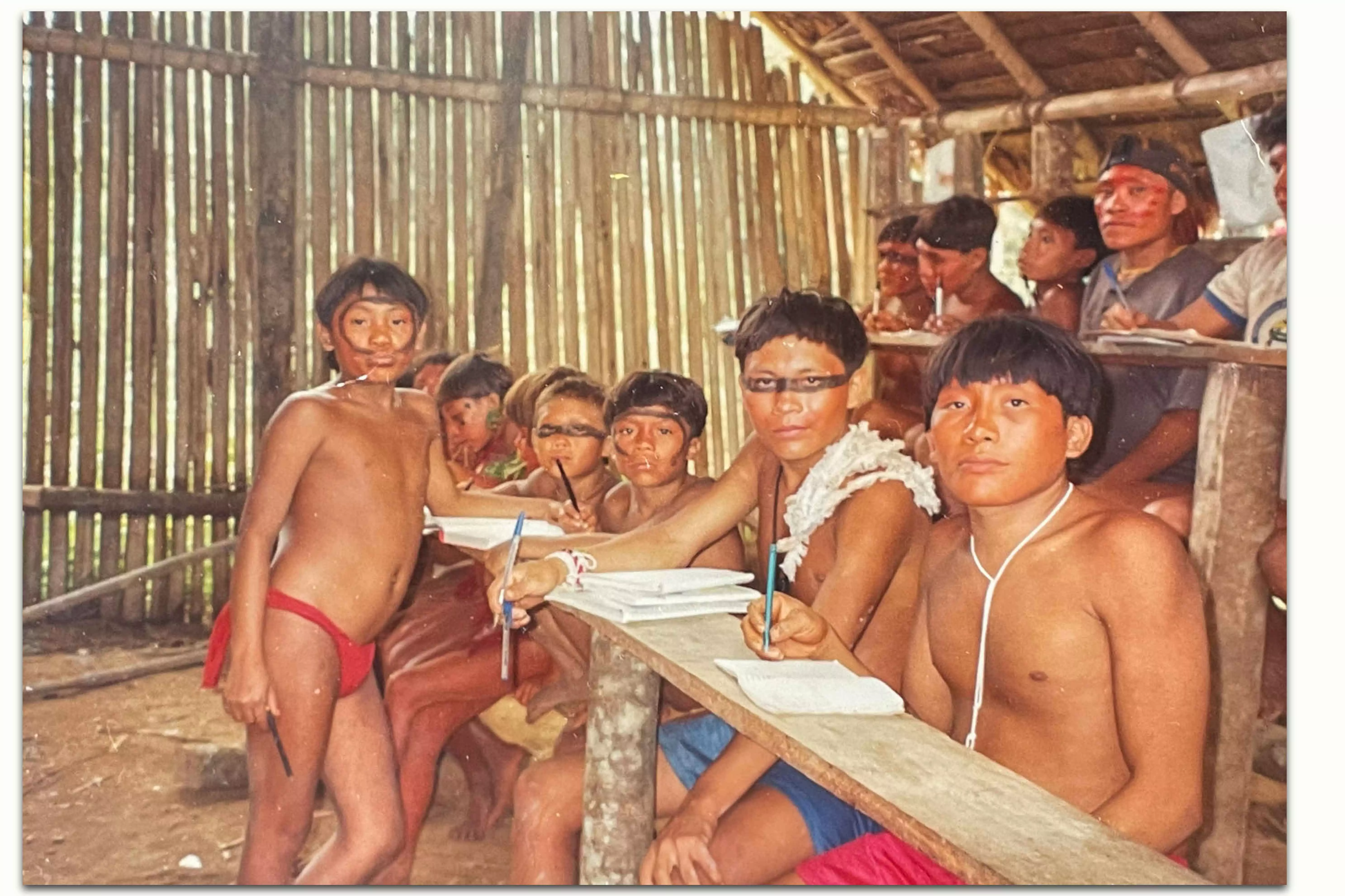

The project went far beyond healthcare. It also encompassed education programs, through literacy in the Yanomami languages programs for Indigenous people, and the training of microscopists – who would later become the first Indigenous health agents. This idea, according to anthropologist Bruce Albert, would be reproduced at the Urihi NGO years later, when the project was expanded. “The basis of the model was to train the Yanomami so they could take part in healthcare. The Yanomami’s social control over care would be permanent and effective, the Yanomami languages would be encouraged as much as possible, and we would take the Yanomami culture and society into account when developing the model. For example: the entire Yanomami system of the exchange of objects, economic exchanges, issues related to death and respect for the dead, and encouraging respect for, and research into, traditional medicines as much as possible. To a large extent the service was guided by the Yanomami.”

CLÁUDIO WITH YANOMAMI PEOPLE AND COLLEAGUES FROM THE PRO-YANOMAMI COMMISSION AND DOCTORS WITHOUT BORDERS, AT THE START OF THE EXPEDITION TO THE SIAPA RIVER, VENEZUELA, IN 1998. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

Deise recalls how Davi Kopenawa always played an active political role, encouraging permanent social control by the Indigenous people themselves. The model, in short, worked, even when facing unusual challenges, such as the building of an airstrip in Balawaú – which lasted two years – as medicines and the healthcare teams themselves had previously reached the areas through long 12-hour walks through dense forest. At the time, says Deise, the experience of the missionary Carlo Zacchini was fundamental. “Carlo was our focal point.” In the region, doctors were the first non-Indigenous people with whom younger Yanomami had contact. “The children ran away when they saw us, they were scared, they ran their hands over our skin, through our hair. That experience of first contact had a great impact on me. It was very intense work. We spent a lot of time in the area. And, on a personal level, it was perhaps the happiest time of my life, because that’s where our daughters were born. We have two girls, one born in 1994, the other in 1996,” says Deise.

The third phase: Urihi (1999-2004)

The Brazilian government decided to restructure Indigenous health in 1999, through a decentralized model, which is when the Special Indigenous Health Districts came into being. The epidemiological profile remained poor in most Yanomami areas. The FNS officially became Funasa. And it was in this context that the Brazilian government invited the CCPY to take the significant step of assuming responsibility for 50% of the Yanomami area. The political situation had also changed, with the congressional approval of the Arouca Law, named in honor of the public health specialist and congressman Sérgio Arouca, who helped create and pass the law in Brasília. Brazil’s president at the time was Fernando Henrique Cardoso, whose sociological and academic vision helped broaden the understanding of Indigenous life.

Luiza Garnelo of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, a specialist in Indigenous health, explains the political context that allowed the Brazilian government, at the time, to seek help from NGOs to provide healthcare for these populations. “The recognition that the Indigenous way of life has unique characteristics that must be respected and that the SUS (Brazil’s national health service) was not adequately prepared to meet their needs led to the proposal to organize a specific health system for Indigenous peoples…The proposal to create a subsystem of SUS prevailed, thus guaranteeing a hierarchical link between these levels (of care),” writes Garnelo in her book “Indigenous Health: An Introduction To The Topic”, published in 2012. With the passing of the Arouca Law, Funasa became responsible for all Indigenous health operations. But it had no staff and no experience. Contracting NGOs which already worked with Indigenous peoples was one solution, as Garnelo explains.

It was at this point that Funasa approached the CCPY. The decision was difficult, and led to a split in the organization, with some, including Cláudio and Deise, believing it represented an important step, as the service model could finally be expanded, and under the responsibility of the Brazilian state. Others, however, thought the massive inflow of government resources into the organization would take away its autonomy and independence, hampering its ability to denounce violations of Indigenous rights. On this side was, most notably, the photographer Claudia Andujar.

“We discussed it internally, and the CCPY decided it was too big a project, involving government funding. Claudia Andujar said at the time that it changed the nature of the organization. It was one thing to run a project in a small area, but something else again to take on a scheme with government funding, which went beyond the interests of the organization itself, beyond the independence needed to criticize the government. The CCPY saw fit to form a second organization, with full support, with its own people, who had more affinity with the area of health. It was me, Cláudio, Carlo Zacquini, Bruce Albert, and Alcida Ramos, an anthropologist from the University of Brasília. We created this organization, and set up a project that included a three-month preparatory stage,” says Deise.

Bruce Albert says Funasa’s proposal was “impossible to refuse”. “We spent years and years, decades and decades, working on the issue of health on a micro scale to create an exemplary project on how Yanomami health could be treated. And when the (federal) proposal to carry it out on a large scale arrives, how could we say no? It would be impossible. So we came up with the solution of creating an association that would be an emanation of the CCPY, but with a completely different legal and administrative framework, a health organization.” There was a great accumulation (of knowledge), says Albert. “I started in 1975, Claudia in 1974, Carlo in 1968, and Alcida in the 1960s too. So, in the 2000s, we already had some mileage in the subject, which really gave us legitimacy. We spoke the language, and we were permanently consulting with the Yanomami. I say this to give an idea of this revolution in care. We took the Yanomami, who had asked for treatment in their villages, seriously, contrary to the idea that you shouldn’t be there.”

Cláudio, says the anthropologist, made the system work and also took care of institutional and political relations. Deise “was Urihi’s epidemiological brain.” “She invented the entire Urihi data management system, to a degree of precision that really impressed me at the time. The system was so well done that, for example, if you had a nursing assistant who didn’t go to the malocas and kept inventing data, the data handling system that Deise invented would immediately detect an inconsistency. It was highly granular. It was extremely well organized and very well thought out. I have the greatest admiration for both of them. it was extraordinary.”

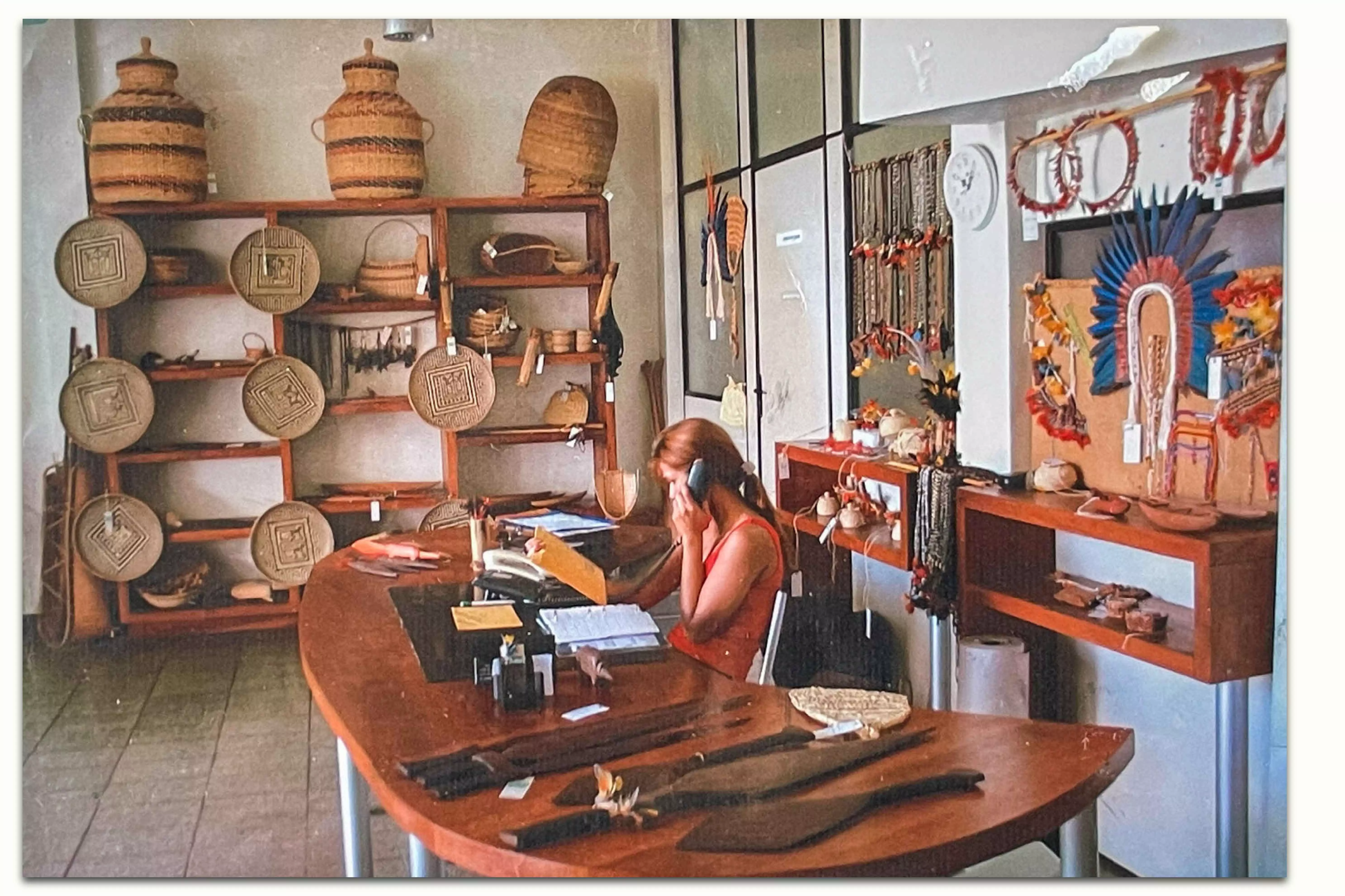

BOA VISTA, RORAIMA, 2000: URIHI-SAÚDE YANOMAMI OFFICES. THE NGO WAS CREATED IN 1999 TO EXPAND A REVOLUTIONARY, HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL HEALTH CARE MODEL INITIATED BY THE PRO-YANOMAMI COMMISSION. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

The anthropologist Alcida Ramos, a professor at the University of Brasilia until her retirement, sees Urihi as the “natural development of the CCPY experience”. “Through actions, albeit periodic, in the field of health, the CCPY contributed to expanding knowledge about the size and conditions of the Yanomami Territory. Urihi, through a highly professional approach, only reinforced the importance of the CCPY. I cannot praise Urihi’s work enough.” Alcida highlights the importance of the administrative management that allowed malaria to be defeated. The model, she says, “should be converted into a manual for other areas of Brazil and the world, such as Africa.” “I witnessed this work when I joined the medical teams in the Auaris river valley as an interpreter. In just four years, Urihi achieved the feat of ‘cleansing’ a large part of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory from the terror of malaria. It turned a health risk into risk-free health.”

Ecologist and geographer Maurice Seiji Tomioka Nilsson, who worked at Urihi, describes the NGO’s work in literacy and training programs for Indigenous people, carried out within the structure of a healthcare project, as “herculean.” “It involved taking people who didn’t know how to write, and teaching them to read and write in Yanomami, and to do math, all using the conceptual tools of our society. How to read a slide, and identify the gamete shapes that malaria takes in the blood, all of that.” Maurice arrived in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in December 2000. “In 2001 malaria was practically eradicated, and there were no deaths from it. For the first time, an emergency care condition changed entirely to a condition of permanent care. There were well-established health centers, generally made with bricks, with accommodation, pharmacies and spaces to attend to patients. And these health posts were always linked to a landing strip, or in other words, to access. When a nursing technician arrived, they got settled, and walked to the villages, which weren’t always next to the airstrip.” One of Maurice’s jobs at Urihi was to transform all the epidemiological information and data into maps.

A friend of Cláudio and Deise for 28 years, Dr Joan Tubau has known the pair since she worked for Médecins Sans Frontières in the Yanomami territory during the days of the CCPY. In the 1990s she and Cláudio went on a mission to Venezuela to investigate cases of malaria among the country’s Indigenous peoples, which was affecting the control of the disease across the border in Brazil. In 2002, Tubau was invited to join Urihi’s board of directors. The effect of the NGO’s work, she says, was “wonderful”. “They ensured staff were present at the health posts, went to the malocas, and respected the Yanomami patients. They made sure the staff understood how incredibly lucky they were to have contact with such a rich culture and people. It’s not about complex diseases. It’s about being there, caring with affection, constancy, concern, and ethics. That’s what Urihi did.” According to Tubau, who is currently back at Médecins Sans Frontières in Barcelona, Urihi introduced telemedicine into the Amazon rainforest. “The nursing assistant was on the radio 24 hours a day, in contact with Cláudio. It was a very effective, ethical and caring system.”

URIHI-SAÚDE YANOMAMI NGO SCHOOL IN THE HAXIU REGION, 2003. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

After Urihi was created, everything was re-scaled: logistics, human resources, qualifications and training, and the locations where the work was carried out. The NGO significantly expanded the care provided in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, but as Deise and Cláudio had experience in caring for Indigenous people, the challenge did not seem overly complex. Funasa gave Urihi complete autonomy. At first the doctors were afraid to take on responsibility for contracting flight hours, for example, which they knew was a hornet’s nest in Roraima, where all the pilots, without exception, had previously worked for the miners. But the Ministry of Health required them to deliver a complete package, as the CCPY had before them.

Recruiting staff wasn’t easy. Callouts for applications were advertised, with doctors mainly coming from the southeast of Brazil; nurses, from the northeast; and nursing technicians from the north itself. Before signing the medical services contract, Funasa management allowed the application specifications to be adapted to the unique characteristics of the Yanomami area. While working towards his master’s degree and doctoral research project in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, the anthropologist Rogério Duarte do Pateo established an informal partnership with Urihi. “Our relationship was logistical support in exchange for information. They took on an enormous region and the data was full of holes. There was no way of knowing who needed to be vaccinated and who didn’t. We had to redo the entire census, understand the relationship between the villages, count every single place. There were places that weren’t even on the list. Places where no one had shown up to distribute medicine for years. Then this routine began. They created base hubs and sub-hubs, smaller installations when the malocas were too far away. They made sure staff had at least some comforts. The sub-hubs always had radio communication infrastructure.”

THE CONTROL OF MALARIA IN THE YANOMAMI INDIGENOUS TERRITORY, BROUGHT ABOUT BY URIHI, REPORTED IN THE FOLHA DE S.PAULO, ONE OF BRAZIL’S LARGEST NEWSPAPERS, IN 2002. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALC NTARA

Rogério recalls the “gadgets” created by Cláudio, such as a mobile x-ray that was taken to the villages to help with the diagnosis of tuberculosis. He also mentions the manual for microscopists, written in three Yanomami languages under the supervision of Bruce Albert. “There was also an innovative system to monitor the medication expiry dates. Flights carried medicine from one hub to another. If they knew there was spare medicine in one place, within its expiry date, and it was running out, or expiring somewhere else, they took it so it wouldn’t expire and go unused … the logistical side of Urihi was very impressive. The strategy was to take as few Indigenous people as possible out of the forest, and to optimize procedures so that they could spend less public money and be more efficient.”

The training of the Yanomami themselves in healthcare made the eradication of malaria possible. “I started working as a microscopist in 1999, in the Urihi era. I took the course and started to monitor the health of the Yanomami. When Urihi started in 2000, the health situation became very good, because staff walked (to the villages), they sent them to work, they didn’t send them to remain at the health posts,” says Morzaniel Ɨramari Yanomami, who was a teacher in the CCPY literacy projects in Surucucu, before devoting himself to healthcare projects with Urihi, and training himself as an Indigenous health worker. “They sent them out to work in the communities, and sleep (there). They walked everywhere,” he says. “Malaria was eradicated, everything got better, the Yanomami were healthy, everyone really liked their work. I used to spend a lot of time with them, so I know the work of Urihi-Saúde Yanomami. At the time, the Surucucu region was a zone of conflict. Dr Cláudio and Dr Deise, who coordinated the healthcare, went into the forest, rather than stay in the city. They took care of the Yanomami themselves. Urihi trained a lot of Yanomami health workers, microscopists, to combat malaria. That’s when everything improved for the Yanomami.”

The indigenous people invited to work for Urihi, who trained as microscopists and health workers, at first weren’t paid in money. Culturally, it made no sense to them. Instead, they were paid in exchanges. In the Yanomami language, the practice is known as “matihipë”, the word Indigenous people use for objects they want to own, such as agricultural tools, machetes and knives, shorts, flip-flops, tools to help with fishing, planting, and hunting, or which bring everyday comforts. “Gradually we managed, towards the end, to pay in cash, with the proper documents, but (before) it was all in exchanges. You can’t imagine how many items there were in our warehouse… That’s why we couldn’t do large tenders for a specific number of fishhooks, for example,” explains Cláudio.

Every three months, Urihi prepared a project report, which included financial information and details of work carried out, and sent it to Funasa. There were also target reports. “We had an administrative sector, an administrator, an administration assistant. We ordered the spending. We signed everything,” says Cláudio. “Our tendering and purchasing procedure was never questioned. Never. We signed four Urihi medical services contracts. In order to receive the next installment, our accounts had to be up to date. This was all approved, and it was never questioned,” adds Deise. Urihi had 120 employees. Sixty percent of the resources from the medical services contracts were used to pay staff, she says. The NGO’s relationship with Funasa’s national directors in Brasília was direct and flexible. “But as time went on, we began to sense resistance from the local Funasa, from Roraima. The coordinators were political appointees, and there was constant hostility at District Council meetings. They were already clearly anti-Indigenous,” says Deise.

Epidemiological bulletins prepared by Urihi and later cataloged by Funasa show the incidence of malaria dropped by 99%, with no deaths from the disease registered in the villages where Urihi provided care between 2001 and 2004. The NGO trained 33 young Yanomami as microscopists. Infant mortality in the period reduced by 65%. Tuberculosis began to be diagnosed and treated in the malocas, whenever possible. The Yanomami children were vaccinated according to the Ministry of Health schedules. There were no more cases of malnutrition. “They really did a unique, exemplary job, which is not only proven by the numbers, but by how the Yanomami describe this period as the time of health, when they lived well, didn’t have to worry about illnesses, and could live their lives,” says the indigenist Marcos Wesley de Oliveira, who worked at the CCPY between 1997 and 2008.

During this period, population growth was 4% per year. “Davi (Kopenawa) used to say, in his village, over in Demini, these are Urihi’s children. Because infant mortality was very high, wasn’t it? Then children stopped dying,” recalls Cláudio.

The end of Urihi

The principal demand of Indigenous leaders was to have a say in the definition of public health policies. The Indigenous movement has long called for a department linked to the Ministry of Health to directly oversee Indigenous care, minimizing local political interference. But this would only become a reality in 2010, with the creation of the Special Office for Indigenous Health, or Sesai. And it was only in 2023 that an Indigenous person, Ricardo Weber Tapeba, became its director. Decades earlier, the existence of Urihi represented a challenge to the structuring of public policies in Indigenous areas, especially in the Yanomami territory.

EXHIBIT AND SALE OF YANOMAMI HANDCRAFTS IN RECEPTION OF URIHI OFFICES IN BOA VISTA, IN THE STATE OF RORAIMA, IN 2003. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

Tapeba, who is on the frontline of efforts to tackle the current Yanomami crisis, had not previously heard of Urihi’s work. Sesai, he says, “has many shortcomings” and the territory “of almost 10 million hectares, more than 350 Indigenous communities and a population of more than 30,000 Indigenous people” poses numerous challenges, especially in terms of access. “As I’m unfamiliar with the Urihi model, I can’t say if it will be replicated today,” he adds. He also stresses that there is a commitment from the current government and from President Lula himself that “the main areas of government which deal with Brazilian Indigenous policy will be occupied by Indigenous people.” “The less party political influence there is in these instances, the better it will be for Indigenous peoples. In the case of the Yanomami, the Special Indigenous Health District was entirely equipped by political groups from the state of Roraima, which allowed the existing health crisis in the territory.”

Davi Kopenawa says he is fighting to make the Brazilian government understand how vital it is that the Urihi methodology is revived. “We are trying to make a model like Urihi’s function, but within Sesai here in Boa Vista there are a lot of people (who support) Bolsonaro. So it’s hard to make it work. But we are trying, we are fighting. It would be much better, so much better.”

According to researcher Luiza Garnelo, between 1999 and 2004, 26 Indigenous associations entered into health services contracts with Funasa to carry out healthcare operations in the Special Indigenous Health Districts of the Amazon. These associations were forced to perform a “profound restructuring of their institutional model and even their political objectives, in order to properly fulfill a new role, that of providing public health services,” she explains. The challenge was not only to have qualified technical staff, but to manage “budget volumes much greater than those they had previously handled, creating great challenges for Indigenous associations,” explains Garnelo, in her book on the parameters of Indigenous health.

Urihi, according to Cláudio and Deise, underwent this process of adaptation, and its staff felt supported through a transparent, direct dialogue with Funasa and the Ministry of Health in Brasília. The relationship with local politicians, however, was never harmonious. In the doctors’ view, Urihi, by providing permanent healthcare in Indigenous areas, became an obstacle to mineral exploration interests in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory.

In 2003, with a change in Brazilian government, the Urihi directors began to sense an even more hostile climate in their relationships with the local political and economic elites. Two years earlier, the country’s senate had already carried out its first parliamentary enquiry into NGOs. At the time, Indigenous organizations warned of the risks of analyzing voluntary sector cooperation with the State in a generic manner, especially in Indigenous areas. At the time, one of the senators behind the enquiry, Mozarildo Cavalcanti – of the Liberal Front Party, the Brazilian Labor Party, and who in 2022 joined the Progressive Party – was identified by indigenists as aligning himself with the economic interests of the mining sector. In a 2001 report by the Folha de S.Paulo newspaper, Cláudio Esteves said the enquiry would help, if carried out in the proper manner.

In addition to the threat of the parliamentary enquiry, the associations working in partnership with the federal government in Indigenous areas were put under further pressure by a new approach to management, which became clear from 2004 onwards. “In 2004, under the Workers’ Party government, Funasa directors took a sudden and unilateral decision to review their priorities in the creation of partnerships,” explains Garnelo in her book. Two ordinances (No. 69/2004 and No. 70/2004), redefined the management structure, centralizing all purchases of supplies and equipment necessary for Indigenous health operations within Funasa. “In practice, the measure implied the removal of all the autonomy of the contracted parties in carrying out healthcare operations under their responsibility, restricting them to the mere role of hiring personnel to work in the Indigenous Health Districts.”

Before these two ordinances, signed by the Health Minister at the time, Humberto Costa of the Workers’ Party, NGOs such as Urihi had autonomy to define their own operations and make fast, flexible hiring decisions, adapting their spending to the reality of care. After them, however, such organizations would no longer have control over the management of healthcare programs in Indigenous territories, but would basically only hire personnel. When asked by SUMAÚMA to explain the reasons behind the change in the management of Indigenous healthcare, Humberto Costa, now a senator, failed to respond. According to his press office, the senator could not remember the reasons that led to the restructuring, and suggested asking former Funasa national director of indigenous health Alexandre Padilha instead.

BOA VISTA, 2000: CLÁUDIO REPORTS THE PRESENCE OF MINERS ON YANOMAMI LAND TO LOCAL NEWSPAPERS. THE CRIMINALS WERE ALLEGEDLY SUPPLYING WEAPONS AND INCITING CONFLICT AMONG THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

“When I took over as director of Indigenous health at Funasa, for about a year, half of 2004 and half of 2005, these two ordinances (69 and 70) had already been published, and were already in operation. I wasn’t involved in creating them. They came about at a time when it was important to have mechanisms through which Funasa could supervise the work of non-governmental organizations,” Alexandre Padilha explained to SUMAÚMA in writing. Padilha is now Minister of Institutional Relations in the Lula government.

He went on to stress that, at the time the management change was made, “actions by the Comptroller General of the Union and investigations carried out by supervisory bodies found misuse and poor management of resources by NGOs, and low quality of performance in multiple locations.” Padilha recognizes that knowledge of local conditions is important in such partnerships, but says this “wasn’t enough to guarantee good resource management.” The objective behind the new ordinances, he says, was to create monitoring and supervision mechanisms for the Ministry of Health. “This model was improved and superseded when we created, years later, a Special Office for Indigenous Health, which brought Indigenous healthcare into the Ministry of Health, which was expanded and strengthened during my tenure as minister.”

Padilha did not answer questions about the Urihi NGO, or say whether he was aware of the work of the indigenist doctors in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, or whether he knew about the cases or the current judgment against them. In 2007, the CCPY website published a statement by Padilha, who is also a doctor in public health, about the work of Urihi: “Funasa’s medical services contract with Urihi produced good results in reducing infant mortality and in controlling malaria in the regions where it worked amongst the Yanomami in the states of Roraima and Amazonas.”

Padilha also told SUMAÚMA that Funasa would not be recreated under the current government. “The Indigenous territory has many special characteristics, and the combination of the public structures of the Brazilian State with the experience of local organizations is fundamental. The best example of this combination was in 2011, and also through Mais Médicos (a government program to provide more doctors), partnerships with local organizations and agencies, or with universities. This was dismantled under the Bolsonaro government and today we have the major challenge of rebuilding the service for the Indigenous population.” The government will again invest, Padilha promised, in the training of Indigenous doctors, health agents, nurses and nursing technicians.

The beginning of the end for Urihi, say Cláudio and Deise, was when the Special Indigenous Health Districts, directly linked to Funasa, became the target of intense local anti-Indigenous political and economic interference. The NGO lost the autonomy to dialogue directly with Funasa in Brasília, and became a constant target of regional hostilities. “We had to go through the regional directors, and the hostility was total and absolute. They questioned everything we did (from 2003 onwards, especially). The quantity of paperwork was exhausting, there was so much administrative work, so much accountability, and we felt we weren’t doing anything (productive) anymore. We were being pressured to simply complete paperwork, to account for ridiculous things,” recalls Deise.

The doctors disagreed with the Ministry of Health ordinances and sensed a political siege developing. As well as confronting local political leaders, Cláudio also clearly expressed his concerns over the fact that Funasa was controlled by figures from the then Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, such as former senator Romero Jucá, who had never hidden his support for mining in Indigenous areas. Jucá even proposed a law in favor of mineral exploration in 1995, well before Bolsonaro would make it a focus of his government.

“From the moment they reduced the medical services agreements to basically hiring personnel, in 2004, we wanted to go,” says Deise, who left the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, after years of tireless work, with a sense of defeat. “It’s surreal, because I knew this was a political defeat. The fact that they didn’t use our experience to build what came next meant there had to be a split. This was symptomatic of how things would not turn out well. And they would not turn out well for the Yanomami.” Funasa even rejected Urihi’s proposal for a transition period to pass on their experience to the new health managers in the Indigenous territory. “It was a defeat, because there would be no continuity. We warned that the NGOs would be co-opted by the local political powers,” she adds.

Cláudio left Boa Vista with sadness, but with a different political perspective to Deise. “I had always thought what we did there could never be destroyed. That the experience was so successful it would be indestructible. Deise was always much smarter, especially politically, than I was. I thought there might be some real setbacks, but not that they would eliminate us, or destroy us completely. We were never forgiven for having denounced the presence of prospectors, which we did systematically.” Urihi’s nursing reports, explains Deise, were also territorial surveillance reports. In addition to epidemiological data, they included information about aircraft that appeared in the area, with their respective identifying prefixes. “As a healthcare system, we carried out surveillance of the airspace and of the mining area. We never neglected that aspect.”

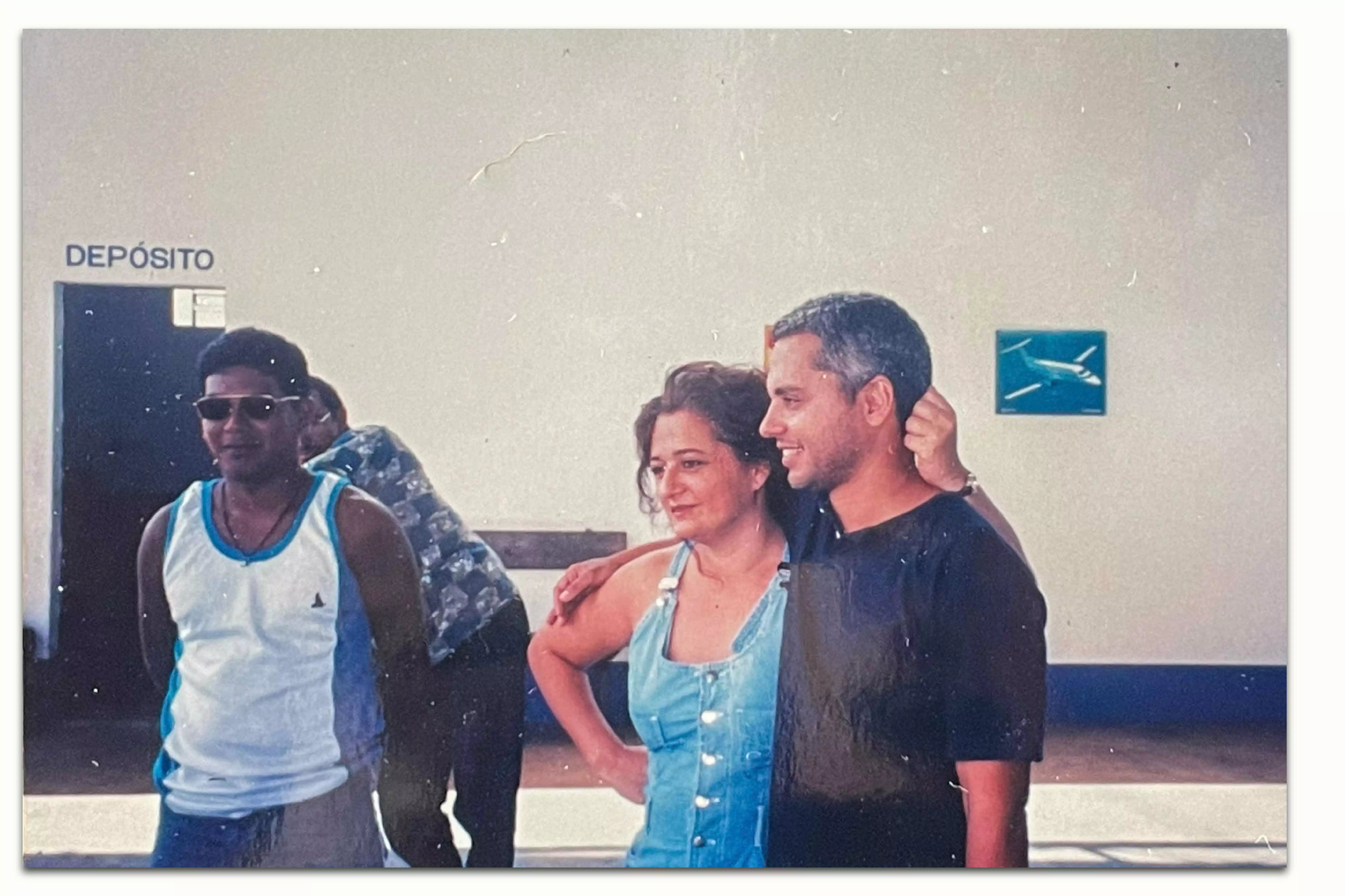

BOA VISTA, RORAIMA, 2003: DOCTORS CLÁUDIO ESTEVES AND DEISE ALVES (R) AND MARINHO (L), AN URIHI INDIGENIST, WAIT FOR A FLIGHT TO THE YANOMAMI TERRITORY. PHOTO: PERSONAL ARCHIVE/UNKNOWN AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

They departed Boa Vista on July 17, 2004. Urihi’s last medical services contract with Funasa came to an end on July 7 of the same year. The doctors decided to try life in Florianópolis in the south of Brazil. A friend had told them that the city had initiated a public hiring process for doctors. Before the move, Cláudio sat the exams and was selected. Adapting was not easy, however, and soon the difficulty of getting a job became clear. The doctors’ reputation at Urihi had already been tarnished by news reports of the first parliamentary enquiry into the Brazilian government’s contracts with NGOs in 2001. In 2007, when a second parliamentary enquiry into the matter began in the Senate, Cláudio and Deise willingly gave up their banking and tax confidentiality to the political authorities, in an attempt to avoid their names being associated with the misuse of public funds. In the same year, the explosive Operation Metastase investigation saw the arrest of 35 people, including Funasa employees and businesspeople, for tendering process fraud, formation of a criminal organization, embezzlement, active and passive corruption, money laundering and economic and tax offenses. Medical service contracts signed by Funasa after Urihi was shut down were investigated. In politics, however, separating the wheat from the chaff is a complex process – and the failure to do so is often intentional.

Despite having passed the application process in Florianópolis, it was two years before Cláudio was offered a job by the city council. He was forced to take shifts in nearby cities to survive, and to work in temporary positions. Deise couldn’t find a job. “I went to work as a doctor at the Banco do Brasil Employee Benefit Fund. People saw my resume, interviewed me, but never offered me the job. My background was very specific, but I had 15 years of experience as a doctor, and worked every day.”

Deise is a discreet, calm and organized person. During the days she spent talking to SUMAÚMA, she cried on two occasions, including when she described an episode involving her daughters. “Sometimes our daughters would come home from school and say ‘People said you work with the Indigenous and there are accusations against you’”. (People) wanted to know where we lived, what our house was like. It was very painful. I could never have imagined that after the work we did, we wouldn’t be able to survive or get a job, and would even have to explain ourselves over the only successful period in the history of Yanomami healthcare.”

Cláudio and Deise carried on, but they had lost their energy and joy. When they met with SUMAÚMA to tell the story of Urihi, a great many feelings resurfaced. At times they spoke enthusiastically about medicine and life with the Yanomami, at others they were overcome by profound sadness and anger. The experience of never again being recognized as qualified doctors, and having their images associated with the theft of public funds, has left deep scars not only on their souls, but on their bodies. Cláudio admits that “total disillusionment” led to depression, “which only gets worse with age”. He suffered constant crises of anxiety and insomnia. They have experienced feelings of disgust and indignation since leaving Roraima. But the worst of all, they both say, is seeing that the Yanomami are once again dying and being decimated.

In Florianópolis, the doctors looked after street dogs, trying to leave the past behind. But the story of Urihi was embodied in them both. To supplement his income, Cláudio also applied to be a doctor with the state of Santa Catarina. Funasa communications still reached them in Florianópolis, but after a while, they gave up following the developments of the case against them. “After being diagnosed with a serious heart disease, my pension as a doctor for the state of Santa Catarina came into effect in June 2014. For the same reason of health, I (officially) received my public pension, for my work at the Center for Oncological Research, in February 2017, after my medical exemption had to be renewed several times,” says Cláudio. When he began to receive his first pension, the couple, still utterly disillusioned, decided to move to Portugal with their daughters.

“We moved because we were tired of being in Brazil. After everything that happened, we couldn’t imagine any professional opportunities. We had government jobs, but it was a different life, every day was the same, and we were used to a little more adventure. We wanted a little more life. I had Portuguese citizenship, and my daughters could get it too, so we thought, why not?” explains Deise.

Cláudio and Deise lived in Portugal with their daughters from 2014 to 2021, taking their eight dogs, which they hadn’t been able to find homes for in Florianópolis, with them. They stopped paying for the Urihi website domain and no longer had access to the NGO’s email addresses. There was no further news of the case. But life in Portugal was not easy either. Being retired, Cláudio was unable to work, while Deise took temporary jobs. During the Covid-19 pandemic, she worked tirelessly on the front lines. She started a PhD in sustainability but was unable to find a thesis advisor. Even in academia, she believes, she suffered the consequences of the defamation caused by the Urihi trial in Brazil. Drained, they returned to Brazil in 2021, during the Bolsonaro government, and went to live in the coastal town of Porto de Galinhas, in the northeastern state of Pernambuco. Their plan was to leave medicine behind for good, and run a small, sustainability-based hotel. But now, after two years, they have realized being entrepreneurs isn’t for them, and are seeking a new direction.

The trial and the final acts

Before June 2004, when Urihi ended its contractual relationship with Funasa, the Brazilian government had never questioned the NGO’s accounts. As Deise explained, an enormous amount of bureaucracy had to be dealt with prior to the release of funds. While they aren’t specialists in public administration, Cláudio and Deise know they would never have kept the Urihi system running if they had had to follow the strict tendering rules established by Law No. 8666. And the Ministry of Health knew this too, so much so that a 1997 statute foresaw practices that would be analogous, but obviously not identical, to those of Law No. 8666. Urihi always made decisions, they both argue, guided by good practices and a commitment to public money. “We were buying as cheaply as possible from suppliers, trying to meet the goals of public administration, economy, efficiency and impersonality. Just like we used to do with the money that came to the CCPY from international organizations: they just wanted to know if it was spent properly. So much so that after Urihi left (the Indigenous territory) the Yanomami Health District budget tripled for the areas where we had been,” says Cláudio.

.

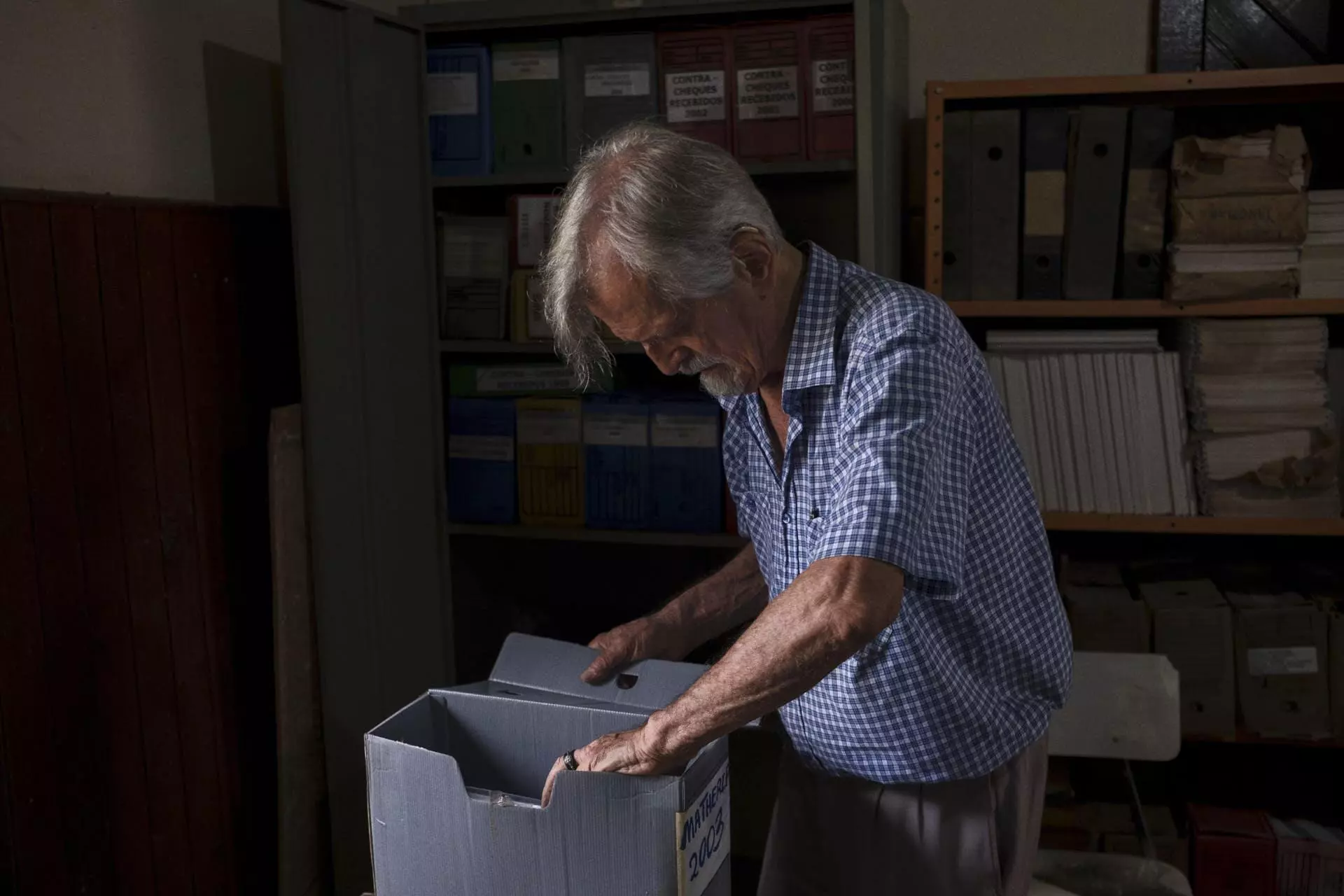

IN THE DIOCESE OF RORAIMA IN BOA VISTA, MISSIONARY CARLO ZACQUINI HAS BECOME THE GUARDIAN OF URIHI-SAÚDE YANOMAMI DOCUMENTS, PRESERVING THE PAPERS AND MEMORY OF THE NGO FOR OVER 20 YEARS. HE PLANS TO INCLUDE THE ARCHIVE IN THE COLLECTION OF THE INDIGENOUS CULTURAL CENTER HE IS CREATING IN THE CITY. PHOTO: PAULO ROBERTO

Certain situations, deep in the forest, were difficult for a bureaucrat to understand. Buying just any microscope wouldn’t work, for example. There was a specific model and brand with a mirror which worked with the reflected sunlight during the day in the villages, and wouldn’t break when transported to the malocas. There was no point in buying a cheaper brand – as Funasa had done years before – which would break quickly and become so much scrap metal dumped in the agency’s offices.

It is also difficult to explain to the supervisory bodies how Cláudio and Deise managed to block the air taxi company cartel. “We invited the Funasa regional coordinator at the time to observe the auction, which involved four companies. They could only submit sealed bids. The day before, one of the businessmen told us he was being pressured into forming a cartel to raise the price.” The winning company, in fact, raised the price of the flight hours significantly. At the end of the procedure, in front of the Funasa coordinator and the businessmen, Cláudio said he knew they had all colluded. The cartel’s scheme was as follows: as soon as the doctors left the Urihi cargo (medicines and equipment) on the runways, the winner would divide it up, so that the other companies would also have cargo to deliver. In other words, there would be a division of money and flight hours, lowering the costs for all of them. But Cláudio and Deise warned the winning firm that they would drop off the cargo, but would then remain at the airport until the plane had taken off, making it impossible for the cargo to be shared with other companies. With no income, these other companies then made lower counter offers to Urihi, and the price of flight hours dropped by 28% in a few weeks. The Federal Court of Accounts found the abrupt drop in prices strange, and Cláudio had to explain the whole story to the court in a letter.

It was also perhaps not easy to understand why Urihi needed so many radio batteries and photovoltaic panels for solar energy. But this was part of the revolutionary telemedicine that Joan Tubau described, allowing Indigenous people to be examined and treated in their own homes. One of the biggest costs in emergency healthcare for the Yanomami is in transporting Indigenous people from the villages to the city. As well as being expensive, it is only an emergency solution, and does not address the root of the problem, as without proper isolation in the villages, or the control of infected people, malaria will continue to be transmitted.

In the two-decade long journey that culminated in the verdict against Urihi and Cláudio Esteves, as its legal representative, the doctor never questioned the need to provide accounts to the Brazilian government. “In the letters I sent to Funasa and the Federal Court of Accounts, I said I thought it was natural for them to ask questions, after all, it’s public money and it shouldn’t be thought strange to have to answer questions. And I’m talking about these unusual cases, which are hard to understand out of context, like this story of the air taxi cartel, for example.”

MISSIONARY CARLO ZACQUINI AT THE DOOR OF THE ROOM WHERE HE KEEPS A LARGE QUANTITY OF OLD DOCUMENTS FROM URIHI-SAÚDE YANOMAMI (MARCH 8TH, 2023). PHOTO: PAULO ROBERTO

In September 2004, the Funasa Property Management Office sent a letter to Cláudio at his address in Florianópolis, saying they had been able to locate certain equipment purchased by Urihi. The doctor replied that same month, giving the delivery dates of the equipment, and explaining that its return had been accompanied by Funasa staff. There had been complications in the delivery process, Cláudio told SUMAÚMA, because most of the equipment was left in the villages, and Funasa had to send employees to verify this, which had not always occurred. Even so, as he explained in his response to Funasa, Urihi carried out an inventory of all the items acquired under the medical services contract and proceeded with the official, “duly documented”, delivery. His response did not satisfy Funasa, however, and the agency’s warehouse manager disputed Cláudio’s version of events. Faced with such discrepancies, the regional management board decided to open an investigation. But it only did so 196 days later. There were, in the end, two enquiries.

It was only in May 2006 that Funasa instigated a federal accounting review of the Urihi era, claiming there was a debt of 22,929.85 reais [$4,464.71 US dollars, using today’s exchange rates] for equipment that had not been located. In June 2006, Funasa’s Administrative Department requested that Urihi, which until then had been classed as “compliant”, be considered “defaulting” in the register. By then, the debt had increased to 36,400 reais ($7,087.64). When notification of this fact was sent to Cláudio by mail, there had been a further correction to 59,100 reais ($11,507.68). Cláudio had moved home in Florianópolis, and did not receive the letter. He would only find out what had happened when the news was published in an official government notice.

In 2007, during a Funasa internal audit, it was concluded that the names of Cláudio and Urihi could not be included in the register of defaulters without the financial documentation from the medical service contracts, “showing approved and non-approved values”, and that only then could the data be entered in Brazil’s Integrated System of Financial Administration. Funasa then requested the issuance of a new legal and financial report, years later. Between all this maneuvering, which included a passage through the Comptroller General of the Union, Funasa initiated three federal accounting reviews of Urihi, one for each of the three medical services contracts.

DOCTORS DEISE ALVES AND CLAUDIO ESTEVES HOLD HANDS WHILE BEING PHOTOGRAPHED. WHEN TELLING THE STORY OF URIHI TO SUMAÚMA THEY AT TIMES SPOKE ENTHUSIASTICALLY ABOUT MEDICINE AND LIFE WITH THE YANOMAMI, BUT AT WERE OFTEN OVERCOME BY SADNESS AND ANGER. PHOTO: BRENDA ALCÂNTARA/SUMAÚMA

In 2013, the documents arrived at the Federal Court of Accounts, annexed in a single legal case. On this occasion, almost ten years after the conclusion of the medical services contract, Cláudio’s debt to the Brazilian Treasury had already leapt from thousands to millions of reais. In 2010 a project report analysis revealed that in addition to missing equipment, Urihi had also failed to meet its overall targets. The end result: it would have to repay 33.4 million reais ($6.5 million). In 2014, the Comptroller General of the Union adjusted the amount to 48.6 million reais ($9.46 million).

Finally, in October 2018, the Second Chamber of the Federal Court of Accounts found against Cláudio and ordered him to repay the debt. The court stressed that it was Urihi’s responsibility to prove how the resources had been applied. “The absence of sufficient elements to demonstrate the proper and regular application of the transferred federal resources, in view, above all, of the absence of the necessary causal link between the federal resources provided and the supposed expenditures incurred in the adjustments, gives rise to the legal presumption of damage to the Treasury in view of the evidence of the deviation of federal funds, proving the proposal of the technical department to convict those responsible in debt to be correct,” reads the final part of the court’s verdict.

Without an appeal, the judgment became definitive in February 2019, the Federal Court of Accounts press office explained to SUMAÚMA. Claudius was tried in absentia and, as he did not present a defense, the court concluded that Urihi had failed to prove good faith in the use of public money. During the legal process, Cláudio tried to hire lawyers recommended by friends. One renowned attorney, however, quoted him a fee of 120,000 reais (around $23,500), which Cláudio and Deise could not afford. At the same time, despite numerous appeals and attempts, they were unable to obtain a pro bono lawyer.

While the civil proceedings against him were in progress, Cláudio was also the subject of a criminal case at the 4th Federal Court in Roraima. In the case, he and Deise were defended by lawyer Ana Paula Caldeira Souto Maior, who at the time, in 2016, was an employee of Brazil’s Socio-Environmental Institute, and who had worked with the doctors at Urihi. This time, Claudio was accused of embezzlement. “In the case, the judge did not receive the charges that initiated the criminal process, and the investigation was dropped, without any examination of its merits, because the period for the State to charge him had already elapsed,” explains the lawyer. In other words, Cláudio never became a defendant. “I wish they had judged its merits,” he says.

In her defense, Ana Paula argued that Urihi’s agreement with Funasa had strict requirements, and that its accountings were duly delivered and never questioned, along with legal documents that proved the honesty and competence of the NGO, and technical project reports. All these accountings, which were approved by Funasa, are also annexed to the Federal Accounts Court case. And, as a former director has stated, in defense of the doctor, previous documents had approved the accounts provided by Urihi.

“Cláudio’s mistake, as director and president of Urihi, was to show it was possible to provide dignified care to the Yanomami, with a reduction in malaria and child mortality due to malnutrition. This is the central point. What he suffered as a consequence came as a result of this. Urihi built the best health posts. The situation of the health posts today, within the Yanomami Indigenous area, is depressing,” says the lawyer, who also states she did not have the technical knowledge to defend Urihi at the Federal Accounts Court, as this was not her area of specialty.

SUMAÚMA consulted two attorneys specializing in public law about whether an appeal would still be possible. Both believed it could be a possibility, but would require a detailed and extensive analysis of the case. As they were only able to carry out a superficial assessment of the case against Urihi, their names will not be mentioned. One thought it would be possible to request a review of the case at the Federal Accounts Court itself. Another sees two other possible avenues: a writ of mandamus at the Federal Supreme Court, or an ordinary legal action at the Federal Court. The path will be arduous, and any compensation will not erase what the doctors have been through. Still without a lawyer, the couple have little hope. But they have decided to tell their story in defense of the Yanomami people.

Still living in Pernambuco, Cláudio, aged 61, and Deise, aged 60, have given up on the hotel business, but do not yet know what their next steps will be. Retired and in poor health, Cláudio no longer thinks about returning to medicine. Deise would like to work as a doctor again, but fears what the case against them may yet have in store. Asked if they could help the Yanomami in the current crisis, the pair are reticent. “We’ve become toxic,” says Cláudio, visibly upset and saddened.

For Deise, the story of Urihi was not about the persecution of an individual. It was the persecution of an idea that challenged, then and now, the economic plans of illegal mining, which puts the Indigenous people under constant threat. “They won’t give up. They’ll keep going. Against us or anyone else who comes forward to disrupt their plans. I’ve always tried to look at it that way, so I don’t get too personally affected.” Cláudio, however, finds it much more difficult to rationalize something that destroyed his name and his health. “Deise is an unbreakable person. I’m at rock bottom. I don’t feel like doing anything else.”

All the Urihi documents – the invoices, accounts provided, approved reports, epidemiological data, work plans, maps, demographic censuses and the methodologies used in Indigenous healthcare – are stored in the Calungá neighborhood of Boa Vista, in the Diocese of Roraima. The missionary Carlo Zacquini has become the guardian of Urihi’s papers, and its memory. “Unfortunately, part was eaten by termites,” he said, via text message. Some documents, he explained, were removed at the request of Cláudio and Deise, so that they could “respond to the attacks of the censors who tortured them for years.” Zacquini considers the legal case against the doctors an “absurd and indecent affair that ruined the lives of people who had become heroes for the Yanomami.” He wants the documents to be part of the Indigenous Cultural Center he is creating in Boa Vista.

“Urihi a kuo tëhë.” Back when Urihi existed. The phrase, recalls Bruce Albert, became a temporal and historical symbol for the Yanomami, of a time when everything worked, deaths ceased and evil did not exist. The current Yanomami tragedy shows that such a time is gone.

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: James Young