The criminal invasion of miners in the Yanomami Indigenous Land, with the consent and encouragement of the government of the far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro, has utterly destroyed entire villages. It not only ruined the rivers and the forest, but disrupted a culture with communities that until not long ago had never even seen a white man and lived in harmony with the jungle, from which they made their living. In the areas the miners ignored (because there were no precious metals), you can still see this balance. It was to one of these, the village Demini, where the leader Davi Kopenawa lives, that we went last August. We took Yanomami women there with us, from areas affected by the mining, to interview them safely for our first story, which revealed the sexual violence fostered by miners in the region. We saw children playing freely among the trees. Families bathing in a crystal-clear river, from which they could drink water without worrying about mercury or the miners’ feces. The gardens were full of food. And from a very early age, boys knew how to make their own arrows for hunting, and girls fished and collected mushrooms – being able to identify without any help which types were edible. Women walked around with their breasts uncovered, adorned with beads and red annatto dye.

Last Friday, I met up in Boa Vista with a group of Yanomami who live in the same forest although their experience and lives have been completely different. They were unlucky because their ancestors established their homes on a piece of land rich in gold and cassiterite (the newly coveted metal). And so, they saw their territory invaded by hordes of men in search of easy wealth. In the group, one of the most combative leaders of Papiú village told me how for years he had fought to denounce the miners, who began arriving en-masse in 2018 and soon expanded throughout the forest. With his life at risk, he gave up the fight and nowadays has an in-depth knowledge of the criminals’ operations. Another man from the Homoxi region, where the health post was taken over by the miners, is ashamed to admit that he now works for the illegal mining camps and prefers to be silent. A woman from Kayanaú, a community that lives off the criminal activity, explains how Yanomami girls trade their bodies for grams of gold, which are afterwards exchanged for extortionately priced goods in the mining camps.

These are communities that have no chance whatsoever to continue to exist in the way their ancestors did. Their social structures have been broken down to such an extent that they may not be able to find their way back. The reports show the brutal murder of a culture and the scale and complexity of the work that will be necessary after the expulsion of criminals from the Yanomami Indigenous Land. Read the main extracts of the conversation below.

SUMAÚMA: I would like you to tell me a bit about the health situation in your region. How are things working out?

Papiú village leader: Where we live nowadays is not good for health. Health is hanging by a thread. I am the leader and I am very worried, I suffer a lot. I feel it a lot.

On Wednesday, some relatives who were drinking at the mining camp, went there [to the health post] and threatened the health workers. Sesai [the Special Office of Indigenous Health] collected them [the doctors and nurses] and took them to the Surucucu health center [another region in the territory]. But now they [the doctors] have returned to work.

Has the goldmining really interfered with your health in the village?

It has really affected us. It has had a very marked negative impact on our thoughts. Our land [has suffered] deforestation. Our rivers are polluted. The river is contaminated. All the fish are contaminated. It’s over. It’s fish riddled with mercury.

We, our Yanomami relatives, have also been contaminated with mercury. People from Fiocruz who came [to conduct a study on the levels of the metal’s contamination in the Yanomami Territory], cut our hair and found mercury. I asked Fiocruz and they said there is nothing that can cure mercury.

And what about food?

Winter really hampered things a lot. A lot of rain. But today [now] we planted our vegetable garden. We already have a garden. It will take a little time, but we have one. We have cassava, banana. Plants take a long time. That is why my people are suffering right now, they are asking for support from Funai [the National Foundation of Indigenous Peoples].

AREA DESTROYED BY MINING ON THE COUTO MAGALHÃES RIVER, KAYANAÚ VILLAGE, ON

YANOMAMI INDIGENOUS LAND. IN THE CENTER, BLUE SHACKS, WHERE THE MINERS LIVE.

PHOTO: BRUNO KELLY / HAY

You are close to Kayanaú, where there is mining inside the community.

Yes. The Papiú, Kayanaú, Homoxi and Haxiu villages. They are all relatives of ours. We speak the same language. Kayanaú is a five hour walk away. Homoxi [is another region that has been hard hit by the illegal mining] I haven’t managed to get there yet on foot. It is difficult, just by plane.

And how are things in Kayanaú?

In Kayanaú they have destroyed all the land, they have destroyed the entire river.

When did the miners first arrive there?

The miners went up the Mucajaí river by boat and then arrived in Couto de Magalhães.

How long ago?

They first arrived in 2018. In 2019 I was in another community, of other relatives.

And what happened when you went back to the community?

I gave an interview to a journalist who lives down there in São Paulo. The miners wanted to threaten me: ‘Hey, where’s the Indian? They looked for me. I ran away. I stayed away for another six months.

Then I came back again.

And these miners were looking for me again.

I fought alone. Our relatives, our friends gave up. I fought alone. They threatened me. At the time I didn’t even get close to them. I just stayed well hidden. When I was there in my wife’s community, a gold miner called Fernando wanted to kill me, he threatened me. He said [to relatives in the community]: ‘This man is not one of your family, he is not your friend. He is from Papiú village. I met him. This man is giving interviews, making accusations,’ he said. I was very afraid. I was by myself. Denouncing them is very dangerous. If you show my picture, I’m going to be very afraid.

I know everything. That’s why I’m so afraid of denouncing them. Alone you are very weak. But I fought, yes.

I helped the operation [against the illegal mining] a lot. I fought together with the Seventh BIS [Jungle Infantry Battalion]. I went to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. ‘This man is making loads of accusations. He is doing the same thing as Davi Kopenawa does,’ that’s what they said. I was afraid to fight. My wife held me back. She told me: ‘You have got to stop fighting’.

Do the miners pay the Yanomami who work for them?

Yes, they do. They pay them money, they pay a percentage.

That’s how they do it. But I never got very close to them, no.

Do the miners harass the Yanomami women?

[He points to a woman who is listening to the conversation] Where she lives, in Kayanaú, they harass the women a lot. [he points to a woman who is listening to the conversation]. They [the miners] are contaminated. They have already contaminated the river. But now the women’s bodies are also contaminated. The miners sleep with a lot of women there. They rape them.

[I’m addressing the woman]. Do the miners in Kayanaú harass you?

Yes, a lot!

Have you got any children by miners?

Yes.

How many?

There is a daughter, a daughter [she starts counting]… There are four.

How big are they?

A little one like this [points to a baby, about a year old].

And are the women married to the gold miners or were they raped?

No, they are not married. They just sleep with them.

Do they use force to sleep with them?

They pay them. A 15-year-old [girl] [receives] 5 grams [of gold], [another one who is 20] [receives] 3 grams. [on average nowadays a gram of gold is worth 300 reais].

And do they use condoms?

No. That’s why they get pregnant.

And have health agents been there to examine these girls for diseases?

No.

[Papiú village’s leader] When the miners want to mess with our women, they first offer a cell phone to negotiate.

Who do they give them to?

To the fathers. ‘So you sleep with my daughter, you can sleep with my daughter’ [says the father]. Then you pay my daughter or you pay me as well. I saw a lot of this there [in Kayanaú]. My daughter is very afraid of the miners. I don’t let them get close to her.

A MINER SHOWS A FEW GRAMS OF GOLD IN AN ILLEGAL MINING AREA INSIDE THE YANOMAMI INDIGENOUS LAND. x MICHAEL DANTAS / AFP

What about the issue of alcoholic drinks? You said that a relative went drinking in the mining camp and threatened the health team.

The miners brought the beer. The strong stuff.

There in Kayanaú it’s all over. Our family lost all the men, only the women are left. It ended because of a fight. There isn’t even a [health] post there in Kayanaú. It closed down because of the miners.

When you see this, how do you feel?

What I think is: I raised this with Funai, with Sesai. I said: ‘Let’s have a meeting there. ‘Let’s put a stop to this violence. Let’s work for our health. That is why today I am very worried. Our lives are over. A great deal has been lost. [There are] firearms. Firearms are dangerous.

Are there a lot of guns?

Yes. The miners brought them in. The miners gave them [the Yanomami men] a lot to drink and they fought. Our relatives are gone. Only the women are left.

How much do the miners pay them for their work?

This one here knows. He lives in Homoxi, where there is a lot of cassiterite. He carries cassiterite. [he points to another indigenous man sitting next to him].

How much do they pay you to carry the cassiterite?

[He points to another indigenous man sitting next to him] We Indians don’t carry it. Only the airplane does [carries it].

Do you know how much you earn when you work for the miners?

[Homoxi] We don’t work. We just go [to the mining camp] for a stroll.

Are there a lot of machines there?

[Papiú village’s leader] There are a lot of machines.

And how do the machines get there?

By helicopter. Everything that comes in is hung underneath the helicopters. Then they take them to the mine. There are big machines, with four cylinders. Everything costs about 40,000 reais.

And how much gold do they take out?

It’s around 200 grams, 300 grams a week. [Between R$60,000 and R$90,000 at the current price].

And how many people work on a single machine?

Four people.

And is this amount divided?

It’s split like this: 2 grams, 2 grams, 2 grams, 2 grams. [The main amount stays with the owner of the machine.]

And are the Yanomami who work there panning for gold?

Yes, there are Yanomami who work with the miners.

And is the price the same for the Yanomami and the white people who work in the ravines [where the machines extract the gold]?

Yes, it’s the same price.

When the Yanomami get the gold, where do they spend it? They don’t come to the city to sell it [because they need to catch a plane]...

With 15 grams they buy a cell phone.

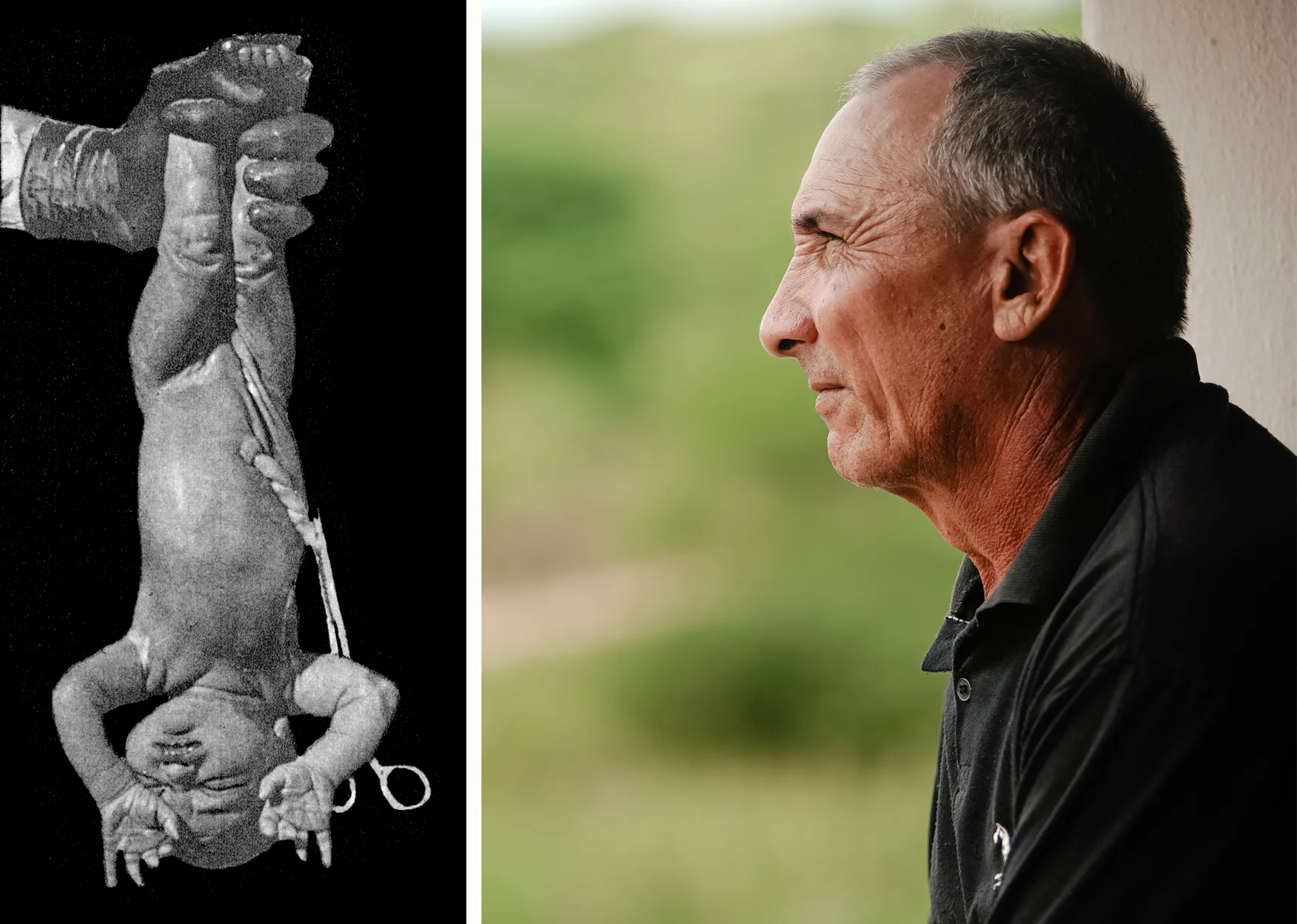

A YANOMAMI WOMAN IS CARRYING A CHILD OUTSIDE THE FIELD HOSPITAL SET UP BY THE

BRAZILIAN AIR FORCE (FAB) IN THE CITY OF BOA VISTA (IN THE STATE OF RORAIMA). PHOTO: Raphael Alves/ EFE

Right there in the mining camp? It costs 15 grams of gold [about 4,500 reais] for a cell phone? What cell phone?

A Samsung. Samsung and Motorola. They say that Motorola is very expensive. Sometimes they charge 10 grams, sometimes 18 grams. When the miners go to the city, they [the Yanomami] also send 15 grams for them to bring things back for them.

Do they charge really high prices in the mining camp?

Yes, very, very high prices. It’s like in a store. You go to one [in the city], you see that a cell phone costs 1,000 reais. In another one, it costs 800. So, you choose where to buy a phone. There [in the mining camp] they do the same thing.

Are there machines in the ravines that only have Yanomami working on them?

No, they all have white people.

And these relatives who work with the miners, what will their situation be like when the miners leave?

They don’t know how to operate the machines like the miners do. But there are those who think: when the miners leave, we’ll do the work ourselves.

Perhaps that’s how they are thinking.

Do they think about continuing to work there without the white people?

Yes, without the white people. They are worried about when the miners leave. The [Yanomami] who work with them [the miners] are worried. They say: my friends helped me, I have learned. I am going to want to work alone. That’s what they are thinking. But we are forbidden, you can’t work with that. If you take precious stones to the city, there in Boa Vista, it will be seen: ‘look, the Yanomami have brought gold. And they will ask: ‘but is there mining there? Are you working there? Take us with you. We are going to close everything down. You can’t work alone, no.

Apart from cell phones, what else do people buy there?

They buy all kinds of things. Flour, rice, sugar, booze, hard liquor, fish. They bring tambaqui fish.

Frozen?

Yes, ammunition as well.

Do the Yanomami buy food at the canteen in the mining camp? How much does rice cost?

One gram of gold, two kilos of rice. A case of beer is the same price. [that’s equivalent to about 300 reais].

And what about sausages?

Five kilos, five grams [1,500 reais].

And guns?

Also.

How much does a gun cost?

Sealed, sealed [brand new] 20 grams [of gold]. A second-hand gun, 18 grams.

What kind of gun?

20 caliber. 28 caliber as well.

And what are the guns used for?

For hunting.

Don’t you use bows and arrows for hunting anymore?

Nowadays we don’t use bows and arrows anymore. Where I live that’s a thing of the past. Only guns. Guns have become really widespread.

Have you ever heard anybody say that the miners have large caliber weapons?

They have large caliber weapons, 16-gauge, 12-gauge.

What do you think your people’s future will be like?

Today, the new generation, they have learned very little of [our] culture. Today I am very worried. Hair, the women cut their hair like we men do. Do you understand? They have lost our culture. I have had lots of battles with them [the young people]: ‘you can’t, you have lost our culture. You can’t give up speaking our language. I told them. The culture has been lost. They wear skirts, they wear lipstick, [they do] their eyebrows. The women are using makeup. No, that’s not our culture.

But I have struggled with them. I talked a lot with them: you can’t listen to music that is not indigenous. What are they singing? What are they saying? [Nobody understands the lyrics] In our language, the woman sings and I listen [understand]. The new generation, the children, they have only used technology. Technology has sucked their thinking.

Do you believe they will think it’s bad that the miners are leaving?

We don’t think it’s bad, we think it’s good. We want to live by ourselves again.

Translated by Mark Murray

YANOMAMI WOMEN WALK THROUGH AN AREA OF FOREST IN THE PAPIÚ VILLAGE, IN A PHOTO TAKEN IN DECEMBER 2014, BEFORE THE MINING BOOM. PHOTO: ALEX ALMEIDA