On June 22, 2010, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, commonly known as Lula, then in his second term in office, visited the city of Altamira in the state of Pará, and gave a controversial speech still remembered in the region. He argued in favor of the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant, which would flood part of the city, submerge islands, harm Indigenous peoples, dry up the Volta Grande do Xingu (which means the “Big Bend” of the Xingu River) and force around 55,000 people, many from traditional forest communities, from their homes. The preliminary license for the project had been issued a few months earlier, in February 2010, despite intense resistance from environmentalists, social movements in the region and Indigenous leaders. “I know many well-meaning people don’t want Brazil to repeat its mistakes in the construction of hydroelectric plants,” said Lula. “Never again do we want a hydroelectric plant which repeats the crime of insanity that Balbina, in the state of Amazonas, represents. We do not want to repeat Tucuruí. We want to do something new.”

Now, almost 13 years later, with Lula having just begun his third term in office, a wealth of facts and evidence reveal that Belo Monte is indeed a “crime of insanity”. Unpublished data obtained by SUMAÚMA show that, in 2019 and 2020, in four Indigenous lands affected by the plant, deforestation was higher than in all the other 311 territories of the Amazon. A generation of children of the forest first saw their homes and islands along the Xingu burned down and drowned and then reached adolescence on the poor outskirts of Altamira, which became one of Brazil’s most violent cities, controlled by organized crime and bloody disputes between factions. Awaiting resettlement so they can go back to their way of life, their families long for a ribeirinho territory that is now under attack by politicians linked to forest destruction and by local land-grabbers and ranchers. Some of these families are confined to so-called “Collective Urban Resettlements,” where they routinely lack water and cannot afford to pay their light bill. Right now, the Volta Grande do Xingu, an 80-mile stretch of river that is one of the most biodiverse regions in the Amazon, home to three Indigenous peoples and to ribeirinho and camponês (traditional small-hold farmer) communities, is drying up, unleashing a humanitarian and environmental disaster.

More than seven years after start-up, Norte Energia has fully complied with only 13 of the 47 socio-environmental requirements of the operating license, according to a technical report issued by Brazil’s environmental protection agency, known as Ibama, and analyzed by Brazil’s Instituto Socioambiental (Socio-environmental Institute, or ISA). These requirements, as the name implies, should be prerequisites to obtaining licenses for both plant construction and operation. Failure to comply indicates an explicit violation of laws.

At least 29 legal filings by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s office point to illegalities in plant construction and operation. In 2022, the supreme court recognized that the federal government had failed to respect Indigenous rights when it did not, in accordance with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, obtain prior, free, and informed consent from the Indigenous peoples in the area. Belo Monte became an internationally cursed name.

The Balbina and Tucuruí hydroelectric plants, cited by Lula, were built in the Amazon by the business-military dictatorship that governed Brazil between 1964 and 1985 and became historic examples of the destruction of the environment and of human and non-human lives. Belo Monte was built by the most left-wing government in Brazil’s democratic history, elected with the support of grassroots movements in the Altamira region. The hydroelectric plant on the Xingu has replicated the violence and damage caused by the Tucuruí plant, and has proved to be as inefficient as Balbina, since, as scientists have repeatedly warned, the water in the Xingu River declines during the dry months.

Some of the impact of the corruption allegations involving recent Workers’ Party governments was softened by the abuses and illegalities of Operation Lava-Jato, or Car Wash [a vast anti-corruption probe that began in 2014] and by the masterful political comeback of Lula, who after 580 days in prison was once again elected president on the back of a broad coalition of support. Belo Monte will not be avoided so easily, however. Belo Monte remains inescapable. Hopes that it could be considered a “fait accompli” and forgotten over time have not materialized. Quite the contrary – in fact, the impacts on the forest and its peoples are far from over. The only reason Lula was not confronted more directly about the issue during his electoral campaign was because the consensus on both left and right was that the fascism represented by right-wing extremist Jair Bolsonaro had to be defeated.

Lula now faces a choice: the decision to renew the operating license for the hydroelectric plant, which expired in November 2021, lies with his government.

It is not the first difficult choice he has had to make about the dam. In 2008, Marina Silva, then Environment Minister, left the government; the following year, she also left the Workers’ Party. Once out of office, Marina called for the postponement of the hydroelectric plant’s tender and questioned the project’s social, environmental, and economic feasibility. “Belo Monte has been on Brazil’s agenda for 20 years. It’s been 20 years since the Indigenous woman Tuíre put a machete to the face of the director of Eletrobras. Regrettably, 20 years have gone by and the license has been granted without resolving the problem of Belo Monte’s social and environmental impacts and the legal issues affecting the land of Indigenous communities. And Belo Monte, in addition to its social and environmental problems, exposes another problem, the question of the economic viability of the project, which today is almost entirely subsidized,” she said in a television interview in December 2010.

Today, Marina Silva is once again Lula’s Environment Minister. The contextual similarities end there, however. It is not by chance that the name of her department was changed to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. If in his second term Lula became the world’s “pop star” president due to the success of his social programs in reducing poverty, on a planet where the climate crisis has become the central concern even in conservative arenas like the World Economic Forum, his government will now be judged on what happens in the Amazon. The name Belo Monte resonates around the world for what it is: an environmental and human disaster. And none of the various statements by Lula and other Workers’ Party politicians defending Belo Monte can erase the millions of tons of steel and concrete erected in the middle of one of the most majestic, biodiverse rivers in the Amazon.

The technical decision on whether to renew Belo Monte’s operating license, and on what should be done about the impacts of the hydroelectric plant, will be taken by Ibama, an agency tied to Marina Silva’s ministry. The political decision, however, will be Lula’s.

During January’s inauguration ceremony, Lula walked up the ramp of the Palácio do Planalto (the official workplace of Brazilian presidents) alongside chief Raoni Metuktire who, as well as being one of the greatest Indigenous leaders in the country’s history, was one of the most significant opponents of the construction of the Belo Monte plant. Many were moved, and even surprised, by Raoni’s presence among the representatives of the Brazilian people who passed the presidential sash to Lula. After all, Belo Monte had forced these two great Brazilian leaders onto opposing sides for many years.

Raoni and Lula had met days before the inauguration, at the same time as Joenia Wapichana, supported by Raoni, was announced as president of Brazil’s federal agency for Indigenous affairs, Funai. Belo Monte was discussed at the meeting. Raoni, once again, alerted Lula to the destruction caused by the dam on the Xingu River, one of the largest tributaries of the Amazon basin and a fundamental part of the lives of the Kayapó people and dozens of other Indigenous groups that live along its banks, from its sources in the state of Mato Grosso to its mouth in the region of Porto de Moz, in the state of Pará.

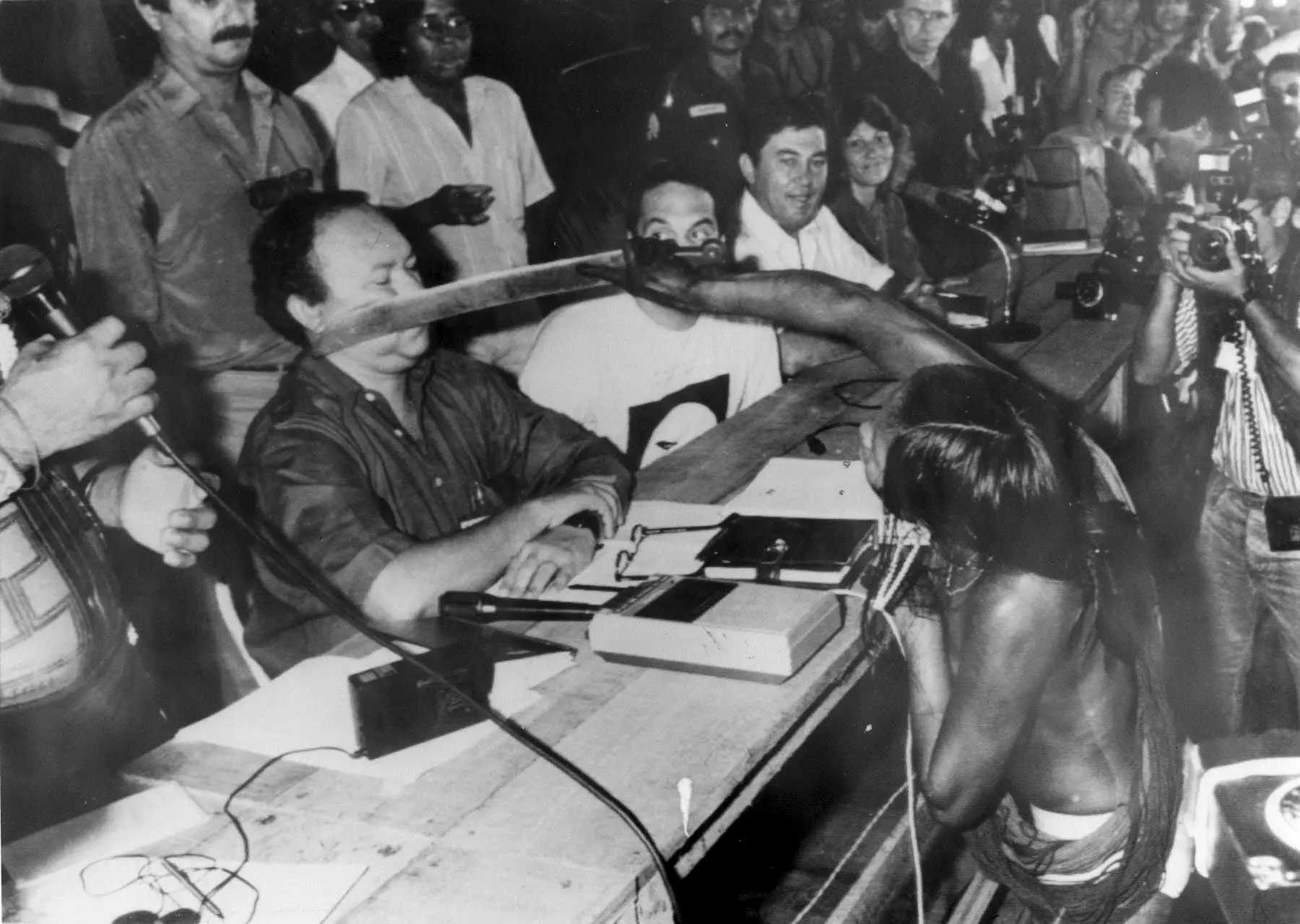

Belo Monte, then known as Kararaô after a war cry of the Kayapó people, was planned by Brazil’s business-military dictatorship. In February 1989, a gathering of Indigenous peoples of the Xingu in Altamira was marked by a scene that became known around the world, when the Indigenous leader Tuíre Kayapó thrust a machete towards the face of Eletronorte director José Antônio Muniz Lopes, an appointee of Brazil’s then president José Sarney, who had worked in the electrical sector for decades. Following the episode with Tuíre, Eletronorte decided to abandon the name Kararaô, and the plant became Belo Monte. The project would only be resurrected at the end of the 1990s, under the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso. This time it was up to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office to judicially block the plant, pointing out a number of irregularities in the impact studies and a lack of consultation with Indigenous peoples.

The moment indigenous leader Tuíre Kayapó holds a machete against the then director of Eletronorte, José Antônio Muniz Lopes, in protest against the construction of the Kararaô hydroelectric dam, today known as Belo Monte. Photo: Protásio Nene/AE (February 21, 1989)

When Lula was first elected in 2002, both the social and Indigenous movements of the Xingu region celebrated, because they thought the case was closed. Yet in 2005 the president guaranteed the approval, at record speed, a legislative decree that allowed the licensing of the works. A tendering process was carried out in 2010, during Lula’s second term, after a legal battle that was lost by the Federal Public Prosecutor, Indigenous peoples, the ribeirinhos (those living in traditional forest communities) and the social movements of the Xingu. At the time, a large part of the more affluent echelons of Brazilian society, along with the press, were in favor of the plant, which was considered a “masterful work of engineering. So much so that a tendering process engineered by Delfim Netto, a former minister under the dictatorship, was allowed to go ahead despite a number of peculiarities before, during and after its realization. The tender was won by a consortium of companies called Norte Energia.

ONE OF THE FIRST PHOTOS OF THE DESTRUCTION CAUSED BY THE OPENING OF THE CANAL SERVING BELO MONTE, TAKEN IN 2012. PHOTO: DANIEL BELTRÁ/GREENPEACE

Decided upon and tendered during Lula’s government, the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant was constructed during the presidency of his successor Dilma Rousseff, by a group of contractors that would later be the target of the anti-corruption operation Lava Jato. In 2015, the plant’s operating license was signed, and in the same year, as the Atlas of Violence (a data source from Brazil’s Institute for Applied Economic Research) would subsequently show, Altamira became the most violent city in the country. The municipality has had some of the highest murder rates in Brazil ever since – in 2019, it was the scene of the second largest massacre in the history of the Brazilian prison system, with 62 dead. In 2020, just before the first cases of Covid-19 reached the state of Pará, the city witnessed a series of suicides among those who had entered their teens in a brutally transfigured city. Mental health experts have linked the suicides to the dam’s impacts.

Paradoxically, Belo Monte brought together two ideologically opposed governments. In 2016, shortly before being forced from power by impeachment, Dilma Rousseff, from the Workers’ Party, arrived in the region to inaugurate the hydroelectric plant. In 2019, Jair Bolsonaro was present as the inauguration was completed.

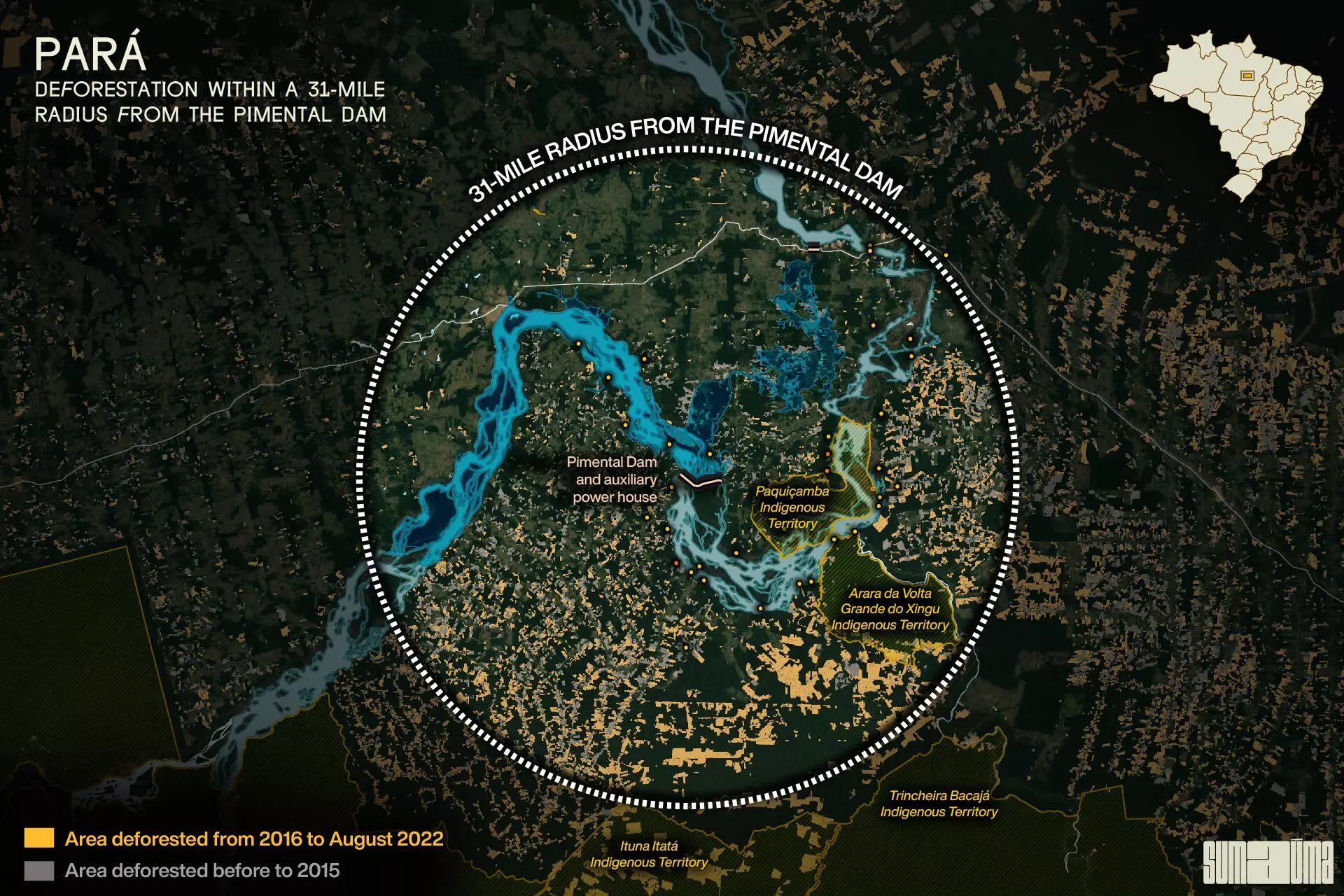

The Bolsonaro government’s principal strategy was to advance into the protected areas of the Amazon. The results became evident with the genocide of the Yanomami people and record numbers of fires and deforestation, which led to the destruction of more than two billion trees. But, even before Bolsonaro, Belo Monte had transformed the Xingu region into the uncontested deforestation leader in the Amazon, with Altamira topping the ranking seven out of ten years, from 2012 to 2021. With Bolsonaro, the destruction worsened.

The plant built on the Xingu has caused harm on a scale commensurate to its vast size, in unmeasured impacts, unforeseen damage, and unmet requirements: the debt to the people of the region and the forest itself is only growing.

By treating the Xingu as its own private water tank, from which it can take or add water according to its needs, Belo Monte is drying up the 80 miles of the Xingu known as the Volta Grande, home to thousands of plant and animal species, some of which are endemic, which means they only exist in the region. If they become extinct there, they will disappear from the planet.

Since Belo Monte’s operational license expired in November 2021, Ibama technical specialists have been assessing its renewal, with no set deadline for their review. According to Brazilian legislation, the plant can continue to operate, as the license renewal was requested in advance. But with each passing month, the environmental and human cost is growing – a cost charged to the account of Lula and the Workers’ Party.

The decision whether or not to renew the operating license may be a unique window of opportunity for a government that has assumed power with a commitment to environmental sustainability and the fight against poverty. It is also a chance for Lula to show the world the true scale of his commitment to the Amazon, the climate crisis and the environment. It is, above all, a choice over establishing his legacy on a planet in the midst of climate catastrophe.

Lula now has a scheduled – and unavoidable – appointment with Belo Monte.

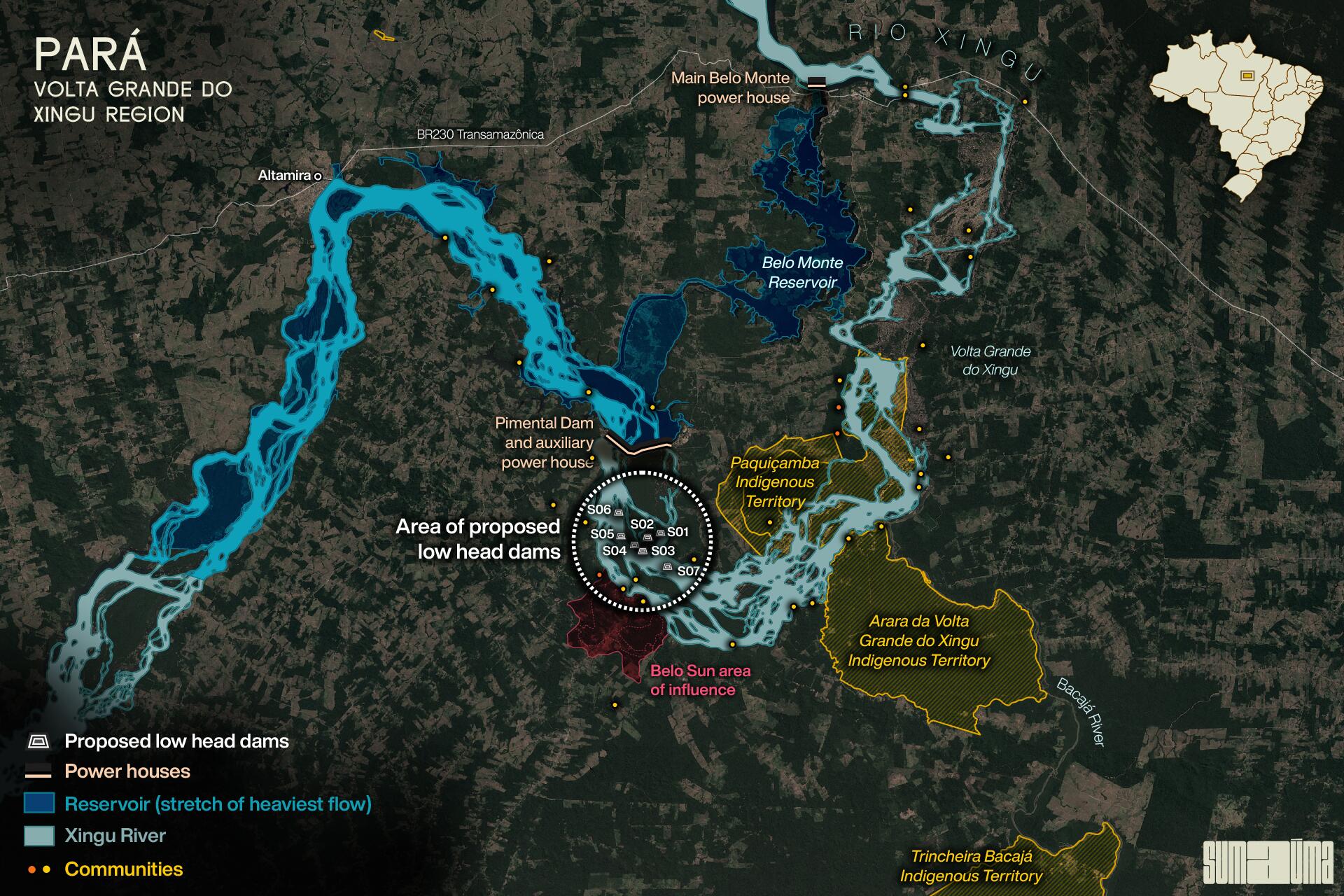

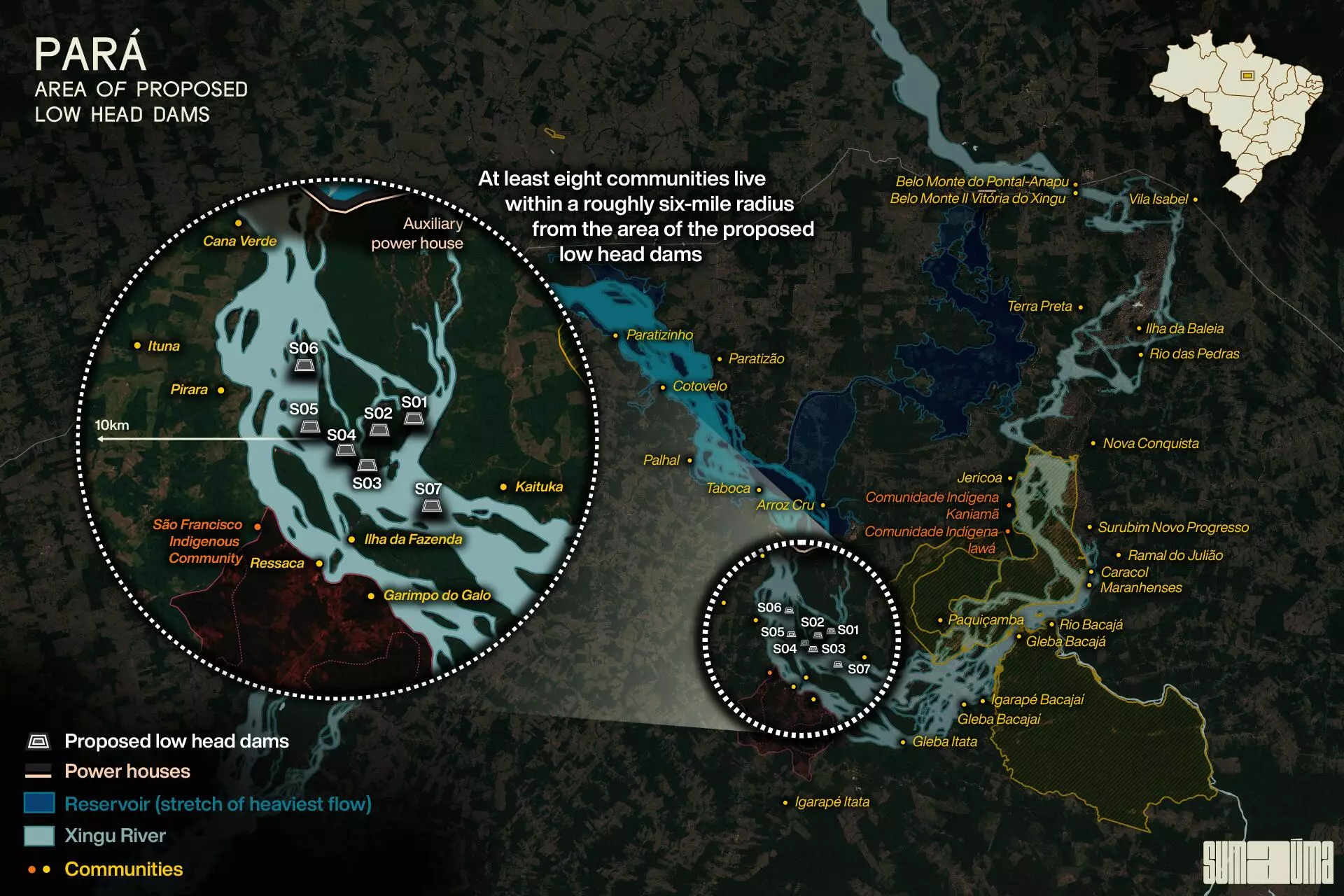

To help the president in his decision, the SUMAÚMA team visited the most isolated communities, Brazilians who can no longer navigate the Xingu, have no access to roads, and who live in poverty, without welfare or social support. Our reporting team was also the first to visit the sites where Norte Energia wants to build seven low head dams on the Xingu river, to avoid having to return part of the water it diverts from the Volta Grande region. We talked to fishermen who for the last seven years have been unable to support their families through fishing, due to damage caused to aquatic fauna that Ibama only recognized in 2019. We also walked the streets of the “Collective Urban Resettlements,” residential areas far from the center of Altamira, built by Norte Energia to house families evicted from their homes because of the hydroelectric plant, who suffer from a chronic water shortage, unaffordable light bills and extreme violence.

ODELITA HONORATO PHOTOGRAPHED NEAR HER HOME IN THE LARANJEIRAS “COLLECTIVE

URBAN RESETTLEMENT”, ONE OF THE HOUSING DEVELOPMENTS BUILT IN ALTAMIRA BY NORTE ENERGIA TO HOUSE FAMILIES DISPLACED BY BELO MONTE. SHE VOTED FOR LULA IN THE HOPE HE WOULD ENACT POLICIES TO HELP YOUNG PEOPLE WHOSE LIVES HAD BEEN DESTROYED BY VIOLENCE IN ALTAMIRA. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA (MARCH 2023)

In addition to their demands and their suffering, one thing all those we spoke to have in common is that they said they voted for Lula in 2022. Despite the disasters wrought by Belo Monte, the Bolsonaro government caused so many deaths that Lula was effectively, for many voters, “Brazil’s salvation”. These voters say they trust the president to make the changes required to stop the cycle of impoverishment and socio-environmental destruction that Belo Monte has brought to the Xingu River. “I would tell him [Lula] to pay attention to the poor, and to our young people, so many of whom are losing their lives to drug trafficking,” says Odelita Honorato, from the living room of her home in one of the “Collective Urban Resettlements” built by Norte Energia. “We hope he’ll find a way to create better conditions for us to work and survive here,” says José Bastos from the state of Maranhão, but who moved to the banks of the Xingu, drawn by the ease of planting fruit and vegetables and transporting produce by boat to sell in the nearest urban centers, until there was neither a way to navigate the river nor roads to travel on. He also voted for Lula.

Living between two islands in Volta Grande, which he has christened Ilha do Amor 1 and Ilha do Amor 2 (Love Island 1 and 2), fisherman Sebastião Bezerra Lima says life became extremely difficult after Belo Monte diverted 70% of the water to move its turbines. “Things aren’t like they used to be, not at all. Neither the fish, nor the ribeirinho, nor the fisherman, nor the Indigenous people, understand the river anymore. In the past, the fisherman and the ribeirinho understood the river, when it ebbed and when it flooded, they understood everything and now they don’t. The life of the fisherman has changed: fruit falls in the dry season, the water doesn’t reach the igapó (area of floodplain forest), the fish don’t feed, and some of the fish that do still exist are as thin as a machete. I lost a lot. The fisherman, the Indigenous person, the ribeirinho, lost a lot,” he says, standing next to an area that should have been flooded since November last year, for fish to reproduce, but in the third week of January remained dry. Even so, the fisherman without a river or fish trusts Lula. “I do,” he says. “If he notices us, we ask that he notices us. I trust him from my heart. He’s here to help the little people. And I’m little, I’m really little”.

A DRY RIVERBED WHERE THERE WAS ONCE A RIVER. SEBASTIÃO BEZERRA LIMA USES RULERS TO MEASURE THE ABSENCE OF WATER FISH NEED TO REPRODUCE. PHOTO FROM JANUARY 2023: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA

What is at stake in the renewal of the operating license

Ibama granted Belo Monte an operating license on November 24, 2015, at the same time as the completion of the Pimental dam which, in the words of the Xingu ribeirinhos, “cut” the river. The plant is known as a hydroelectric complex as its engineering plan includes two dams, two reservoirs and two powerhouses [structures that house generators and turbines]. Pimental is the main dam, which blocks part of the flow of the Xingu in the area before the river reaches Altamira, while diverting another part to a second reservoir, an artificial channel which transfers the water that should flow through the Volta Grande region to the main powerhouse. For local residents, “cutting” the river is an accurate term, as Pimental has left them without water.

With its decision on whether or not to renew the operating license imminent, the Brazilian government has the chance to at last respect the technical reports, consider the views of the dozens of scientists who monitor the impact of construction of the power plant, ignore political and economic pressures and respond to the demands of Xingu voters, putting right the numerous problems the hydroelectric plant has caused and turning its words about the protection of the Amazon into reality.

“We can no longer take environmental issues, and especially socio-environmental issues, lightly. We constantly talk about the role these traditional communities play in environmental conservation, and their importance for understanding what happens in the region, for generating knowledge and sharing natural resources, and for ways of living that are sustainable for the Amazonian ecosystem. But all we’ve done is intervene in ways that put this in danger, which completely destabilizes the ecosystem and the life of these communities. It’s more than time for a new strategy for these projects in the Amazon,” warns Jansen Zuanon, a leading specialist in Amazonian ichthyology, a retired professor at the National Institute for Amazonian Research, and a member of an observatory that brings together researchers and local residents to monitor the damage caused by Belo Monte in the Xingu region.

André Sawakuchi, a geologist and professor at the University of São Paulo, who is also a member of the research observatory, warns of the need for a more up-to-date understanding of deforestation so that Brazil remains in step with the global debate on the climate crisis. “The destruction of alluvial forests is also a type of deforestation. What we have to weigh up in this discussion about Belo Monte is how much more biodiversity we’re willing to sacrifice to generate power. Is the destruction of all these ecosystems and forests, not to mention the loss of riverine and Indigenous cultures, worth it? There is still a solution for the Volta Grande region. We can still save it, if we prioritize guaranteeing the life of ecosystems and communities. But we need to decide how much we’ll sacrifice.”

Under Brazilian law, an operating license should be granted when the requirements of the previous licenses – preliminary and installation – have been fully met. In the case of Belo Monte, they weren’t. Both the Federal Public Prosecutor’s office and civil society organizations, such as Brazil’s Instituto Socioambiental, stated state that items on the previous licenses remain pending. And failure to comply with these requirements has caused tragic damage to people’s lives and to the region’s ecosystems. Licensing mistakes, whether deliberate or not, have played a central role in making the Altamira region the most deforested part of the Amazon over the past decade.

In an assessment of Ibama’s latest technical report, issued at the end of June 2022, the Instituto Socioambiental analyzed the compliance status of 47 of the socio-environmental requirements of the plant’s operating license. As SUMAÚMA can exclusively report, data show that Ibama considers only 13 of these as met by Norte Energia.

In other words, after all the licenses had been granted and seven years since the plant became operational, only 13 of the 47 required measures had been fully met. Another 21 remain in the process of implementation, eight have been partially met, and nothing at all has been done about two. In addition, nine requirements have yet to be analyzed, including that which is perhaps the biggest dilemma facing the hydroelectric complex: the sharing of water from the Xingu to guarantee the life of the ecosystems of Volta Grande.

Among the requirements considered as yet unmet or with pending elements, according to the Ibama technical report, are the resettlement of affected peoples, basic sanitation in Altamira, and compensation and mitigation measures for the region’s traditional populations for the loss of fishing activity. Such requirements directly impact the quality of life of thousands of residents in the region.

Issuing Belo Monte licenses when requirements have not been met is an explicit violation of Brazilian legislation, with serious consequences for the forest, its peoples and the residents of Altamira. When deciding whether or not to renew the operating license, Lula and Marina Silva will show whether the Brazilian government will continue to accept non-compliance with the law, thus permitting serious environmental and human damage in the Amazon – or if Norte Energia will finally be required to comply with these requirements.

In a written statement to SUMAÚMA, Norte Energia said that “no requirements remain unmet. Requirements have been or are being met. The licensing agency, Ibama, is following up on this regularly.” For its part, Ibama informed SUMAÚMA that “Norte Energia’s obligations are either pending, in the process, or already met.” The licensing agency pointed out that the company has been asked to provide “supplementary information” and that “recommendations have been made that would bring works in line with licensing guidelines.” Ibama is waiting for its technical team to finalize analyses before issuing any definitive statement about whether Norte Energia has met operating license requirements.

Pimental is the main dam of Belo Monte. In the words of the Xingu ribeirinhos, it “cuts” the river. PHOTO FROM JANUARY 2023: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA

Fishermen without fish – or electricity – for seven years

It is easy to understand why fishing was one of the main economic activities in the municipalities affected by Belo Monte – Altamira, Vitória do Xingu, Senador José Porfírio, Brasil Novo and Anapu. “The Xingu was our mother,” say many fishermen in the region, when talking about how the dam has affected their lives. No longer. While both the authorities and Norte Energia for many years denied the impact of the dams on fishing , based on impact measurement methodologies much questioned by scientists, the harm caused was officially recognized by Ibama in 2019.

JANUARY 2023: IN THE CENTER OF ALTAMIRA, MEMBERS OF FISHING COMMUNITIES WAIT IN LINE FOR NORTE ENERGIA’S COMPENSATION PROGRAM PAYMENTS: 20,000 REAIS (ROUGHLY USD 3,900) FOR SEVEN YEARS OF LOSSES. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA

The Federal Public Prosecutor’s office in Pará, which has already filed 29 legal actions questioning the plant’s licensing and impacts, states there is no longer any doubt over the serious damage caused by the Xingu dam on fishing stocks and activity in the region. The flooding decimated the areas of igapó around the reservoir and the diversion of water in the Volta Grande do Xingu region made fish spawning and feeding unfeasible, drastically reducing the income of fishermen.

Norte Energia itself acknowledged the damage last year, and invited around 2,000 fishermen to register in order to be eligible to receive 20,000 reais (around USD 3,900) for the losses they’d suffered. The proposal caused revolt, however, mainly due to the low value of the compensation, deemed derisory when considering the seven years of lost earnings, the low number of fishermen considered eligible (estimates put the number of people impacted as high as 7,000) and due to the requirement to register as fishermen, which is impossible for many, especially those from ribeirinho and Indigenous communities, who live from subsistence fishing.

Still, when summoned by the company, fishermen from several distant communities made their way to a school in the center of Altamira for the first day of registration, on January 16. Many said they were going hungry and living on handouts and, with no money to pay the bills, had no electricity. They also reported the disappearance of many fish species, including the most in-demand which had the greatest commercial value, such as pacu de seringa, matrinchã (brycon) and curimatá. The economic impacts are mounting up and growing more severe in a region where just a few years ago fishing guaranteed a comfortable, autonomous life for fishermen, ribeirinhos and Indigenous people.

The company did not grant the press access to the first day of registration but outside, Orlando de Oliveira Queiroz, one of the oldest residents of the Volta Grande region, waited for his wife, who had gone to register. “For us, who are born and raised here, it’s all over,” he said. “The river is gone, the dam wall ruined the rest and they want to build seven more dam walls down there, to trap water.”

“FOR US, IT’S ALL OVER,” SAID ORLANDO THE FISHERMAN, WHILE HE WAITED FOR HIS WIFE TO REGISTER FOR THE COMPENSATION PROGRAM. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA

Orlando, who in a land of so many fishermen has adopted “Pescador” (Fisherman) as his nickname, was talking about the plan Norte Energia has presented to Ibama which, once again, threatens to forcibly remove people from their homes. The proposal foresees the construction of seven so-called low-head or smaller dams, which would supposedly reduce the damage caused by the diversion of water from the Volta Grande region. According to the project, these dams would create flooded areas, allowing fish to feed and aquatic life to reproduce in igapó forests. Ibama, however, has already said they won’t serve that purpose. At the same time, although he doesn’t know for sure, Orlando Pescador, who lives close to the area where the low head dams would be built, may be compulsorily removed from the island where he has lived for over 40 years. If Ibama approves to the seven new dams, the project itself calls for the eviction of seven families from the region.

In August 2022, at a public hearing, the fisherman Raimundo Gomes said the difficulties he has experienced have damaged his health: “First of all, these public authorities need to see us as human beings. I’ve lived my whole life on the Xingu River and today I no longer fish because the river has gone. Norte Energia wiped out our [fish] species, our islands and beaches, our leisure and then wiped out the fishermen themselves. We need the authorities to act to force Norte Energia to pay what we’re entitled to. Mothers and fathers are in the dark, cooking over open fires, because they can’t pay for electricity or gas. There are people who haven’t had power for over a year.”

In its statement, Norte Energia denies that it changed its position regarding Belo Monte’s impacts on fishing. The company says potential impacts on ichthyofauna were taken into account right from preliminary environmental studies and that it has been enforcing mitigation measures aimed at those who make their livelihood fishing since 2017, “when, during a technical seminar with the environmental agency [Ibama], it was decided that, in order for the process of proposed mitigations and compensations to be more assertive, an in-depth survey of the fishing occupation and its economic chain would need to be conducted within the venture’s area of influence.” The company claims that it used these registrations to arrive at the figure of 1,976 fishermen due to receive compensation. In the same note, Norte Energia recognizes that it was obliged to pay compensations for fishing-related losses after Ibama released its technical report and that the proposed amount “takes into account the amount equivalent to the government subsidy paid during spawning season, when fishing is banned.”

IN THE LARANJEIRAS HOUSING DEVELOPMENT, FAMILIES REMAIN INDOORS AT NIGHT TO PROTECT THEMSELVES FROM THE VIOLENCE. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA/SUMAÚMA (JANUARY 2023)

The electric rates charged by the concessionaire Equatorial Energia, which has operated the service since the privatization of electricity distribution in Pará in 1998, is a recurring complaint in all communities, whether urban or rural. In the Laranjeiras neighborhood, where part of those displaced by the hydroplant were resettled, electricity bills can be as much as 200 reais (around U$40) per month, even for houses with just a fan, a refrigerator, a television and a few lightbulbs. After being driven from their homes and from the river by the dam, and now living beside it, Belo Monte’s victims pay one of the most expensive energy bills in Brazil.

In a written statement, Equatorial Pará said that each utility bill would need to be analyzed individually to explain the charges. “However, some factors like energy drain and poorly maintained home appliances can contribute to increased consumption,” the company stated.

Ribeirinhos without a river

The full compensation due to the ribeirinhos of Xingu was only recognized by Ibama in 2018 following significant pressure from the affected populations. It is still a long way from completion. The expulsion of these families from their homes in 2015, without recourse to an adequate resettlement program, marked the beginning of a lengthy process to recognize the many impacts of the Belo Monte plant on their traditional way of life. An inter-institutional space called “Ribeirinho Dialogues” was formed to implement solutions with the input of public agencies and the Federal University of Pará. In June 2016, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office filed a request for the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science to conduct research on the ribeirinho communities removed from the Xingu River so they could propose well-founded compensation measures that would allow them to reconstruct their way of life. The result was a book called The Expulsion of Ribeirinhos from Belo Monte, edited by the anthropologists Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, professor emeritus of the University of Chicago and retired professor from the University of São Paulo, and Sônia Magalhães, one of the most noted scholars on the impacts of Tucuruí, vice-president of the Brazilian Association of Anthropology and professor at UFPA.

The most notable outcome of this mobilization was the creation of the Ribeirinho Council, a space for communities to organize and advocate for their rights and their return to the rural areas near the banks of the Xingu River. We spoke with council member Rita Cavalcante as she stood in line to register her fishing license on January 16. Although her name begins with the letter R, Rita stood with people whose names begin with the letter A. The evening before, a phone call from a Norte Energia employee had asked her to step in for her late husband, Alberto Benício da Silva, who had died three years earlier, before seeing them resettled to their rural homes or receiving any compensation for damages to the fisheries.

Of the 322 families expecting to return to the rural area near the Xingu River, Rita said, only 36 have been resettled. The others still live on the outskirts of Altamira, where they await their return to the river and to their former way of life. Many are experiencing hunger for the first time, their only financial support the 900 reais (about USD 175) per month they get from Norte Energia—not nearly enough to cover the cost of living in the city, far away from the river. The sluggish resettlement process, and the grief they feel at having their lives on hold for several years, has led many to fall sick or die. Others have simply given up.

An entire generation of ribeirinho children has come of age on the outskirts of Altamira, growing up apart from the river and exposed to various forms of violence. It bears remembering that many ribeirinho families were expelled from the Xingu River after their heads of family used their fingerprints to sign documents they could not read under significant coercion from Norte Energia and its retinue of lawyers, and without the legal assistance, mandated by the state. Federal public defenders reached Altamira only in January 2015, in the final stretch of this ploy to violate basic human rights, following pressure from the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

“They even used threats to get us to leave our homes in Xingu,” said Rita, remembering a time when a barge hired by Norte Energia sailed along the banks and islands of the Xingu River carrying machines to knock down and set fire to the ribeirinhos’ houses. The residents watched in terror as the vessels they referred to as demolition barges cruised up and down the river. “After all our fighting, we’re still waiting to go home to the river,” she said. “The company insists there’s nothing they can do. They make things harder, even scare us. So, a lot of people have given up their right to the land.”

SUMAÚMA asked Norte Energia about the ribeirinhos’ situation. The company said these communities had already been taken care of through resettlement in the urban area of Altamira: “The return of these ribeirinho families to the banks of the reservoir is a result of the company’s talks with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Ribeirinho Council, and other parties, and is part of a roster of commitments undertaken by Norte Energia in order to comply with environmental licensing requirements. Therefore, out of respect for and attending to the concept of this traditional way of life, which entails double residency, one of which is along the river, in a direct relationship with artisanal fishing, and with subsistence and extractivist activities, Norte Energia is in the process of returning ribeirinho families to places located in the reservoir’s Area of Permanent Preservation, with monitoring by Ibama and also by the ribeirinhos’ community council and their support group.” The company also says it awaits the issuance of a Public Utility Declaration, a legal instrument that permits the purchase of land for the settlement of families in rural areas along the river.

Ibama disagrees with the number of resettled persons reported by the Ribeirinho Council and says that 121 families have already been resettled in the area around the Xingu reservoir. “Steps are now being taken to resettle the remaining 201 families; however, there is no forecast date for the conclusion of this action,” says a statement issued by the licensing agency’s press office.

Record deforestation in Indigenous territories

“Indigenous component” is the technical name for the chapter in the licensing process that relates to the Indigenous peoples impacted by Belo Monte. Its evaluation rests with Funai, Brazil’s federal agency of Indigenous affairs. The question of whether or not to renew the hydropower plant’s operating license will pose a significant challenge for Funai’s first Indigenous president, Joenia Wapichana, and for the newly formed Ministry of Indigenous People, headed by Sonia Guajajara.

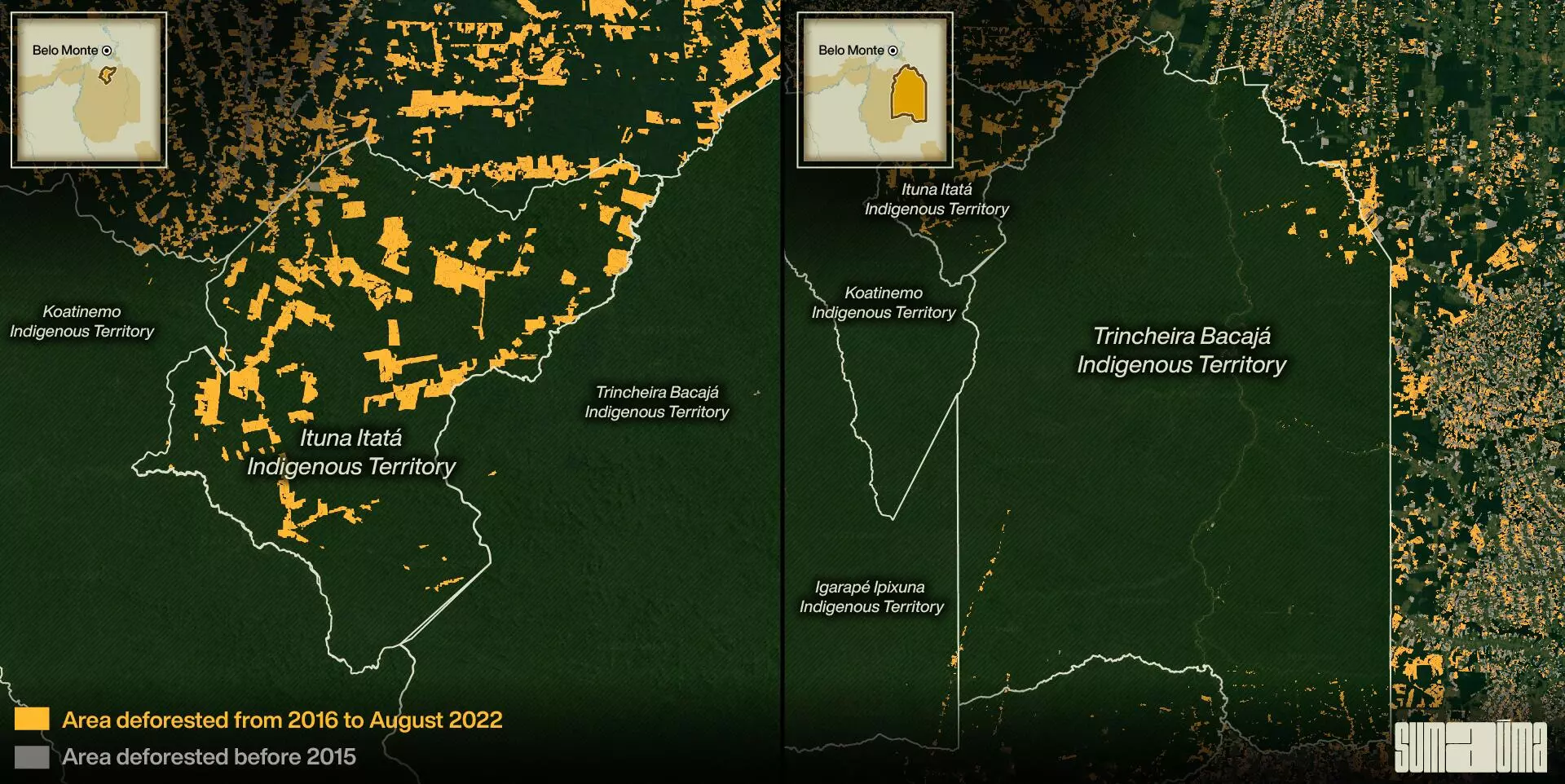

One such challenge is the requirement to protect Indigenous territories from destruction and invasion, a risk foreseen in research conducted during the preliminary license phase. While the Federal Court ordered Norte Energia to build surveillance bases to prevent invasions and conflicts in indigenous territories, part of these structures were only delivered in 2016, after the plant became operational. This delay is a direct consequence of intense pressure from land-grabbers, loggers, and illegal miners in the area. In the past few years, Cachoeira Seca, of the Arara people; Trincheira Bacajá, of the Xikrin people; Apyterewa, of the Parakanã people; and Ituna Itatá, of the uncontacted peoples, broke record after record, becoming the most deforested Indigenous territories in Brazil. The negligence has been even greater in the cases of Cachoeira Seca and Ituna Itatá: to this day, Norte Energia has yet to install control bases in these territories.

THE “FREE FOR ALL” CLIMATE OF DEFORESTATION ENCOURAGED BY JAIR BOLSONARO’S TIME IN OFFICE WAS A TRAGEDY FOR THE INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES, WHICH HAD ALREADY SUFFERED FROM THE NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF THE PLANT. THE PHOTO SHOWS THE TRINCHEIRA BACAJÁ TERRITORY, IN ALTAMIRA, DEVASTATED BY LAND-GRABBERS. PHOTO: LALO DE ALMEIDA/FOLHAPRESS (2019)

In a technical report released exclusively to SUMAÚMA, Xingu + Network, an Indigenous organization that tracks deforestation in the Xingu region, notes that since the hydropower plant began operations seven years ago, the Indigenous territories around Belo Monte have become the most deforested territories in the entire Amazon basin. In 2019 and 2020, which correspond to the first two years of Jair Bolsonaro’s government, a “free for all” climate led to increased deforestation across the biome. But of 311 Indigenous territories, the four that experienced the greatest damage were all in Belo Monte’s area of impact: Apyterewa, Ituna Itatá, Cachoeira Seca, and Trincheira Bacajá.

According to the Xingu + Network, destruction began to escalate before the operating license was issued in 2015, when the Belo Monte construction site was demobilized. This impact had been anticipated and should have been contained. With the loss of jobs, many of those who had migrated to the region from all over Brazil to work on the plant’s construction resorted to illegal activities in order to survive. Although territorial protection measures had been put in place to combat this, it took Norte Energia several years to enact them, often inadequately. The completion of measures for land regularization and the removal of invaders in the affected areas is also still pending. This inaction has wreaked years of devastation. 2019 alone saw the destruction of 30,000 hectares of forest in the four Indigenous territories with the greatest deforestation. “To contextualize the sheer magnitude of the deforestation in Indigenous territories, specifically, we should note that the area in question accounts for 61% of the total deforestation of Indigenous territories in the legal Amazon region,” the report states.

The removal of illegal invaders and the relocation of so-called “good-faith squatters”—which includes ribeirinhos who have lived in the region since the start of the last century and settlers who moved to the region decades ago when the dictatorship summoned them to the area to build the Transamazonian highway—should have occurred in the Indigenous territory of Cachoeira Seca. The report goes on to note: “With the absence of a removal process, deforestation in the territory of the Arara people has not so much decreased as it has increased. According to data obtained by Prodes [a system for detecting deforestation housed in the National Institute for Space Research], deforestation in Indigenous territories increased 24% in 2017. In the three subsequent years, deforestation in Cachoeira Seca totaled 18,700 hectares, a figure higher than that of the previous decade, which totaled 18,000 hectares. More than 7,000 hectares of Indigenous land were deforested in 2020 alone.”

The Apyterewa Indigenous Territory should also have seen the removal of invaders before the hydropower plant began operations, as promised to the Indigenous Parakanã people when research on the plant was first conducted. This promise was never kept. As a result, deforestation increased 237% between August 2017 and July 2018, and 350% between August 2018 and July 2019. The Xingu + Network believes the situation to be out of control. “In September 2021 alone, 2,480 hectares of land were deforested in Apyterewa. This is the highest deforestation rate recorded in Indigenous territory in the past decade. In 2022, the deforestation rate did not cool, with an additional 6,200 hectares of vegetation suppressed in Indigenous territories in August,” the document affirms.

The Ituna Itatá Indigenous Territory is inhabited by isolated peoples and is protected under a special restricted use law. Despite this, there has been much pressure to open the area up. In 2022, a legal decision had to be issued to force the then president of Funai, Marcelo Xavier, who is also a federal police chief, to renew this decree. Located just 45 kilometers from the Belo Monte hydroelectric project, the territory’s forest resources were plundered, with deforestation increasing 295% in the years 2015 and 2016—and 478% in the years 2016 and 2017. “But 2019 saw record invasions and deforestation in Indigenous territories, with nearly 12,000 hectares of forest being razed,” the report states. Deforestation rates fell in 2020 thanks to coordinated operations by Ibama’s inspection teams, only to rise again in 2021 and 2022.”

Sixty percent of all recorded deforestation in the Trincheira Bacajá Indigenous Territory, occurred between 2017 and 2021. Once the Belo Monte operating license was issued, the territory of the Xikrin people underwent increased devastation, with vegetation suppression rising from zero to 4,000 hectares. “2019, the year with the highest deforestation rate, saw the destruction of more than 3,400 hectares of forest.” After images of the Yanomami genocide sent a shock through Brazil, and in response to a request from the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, supreme court justice Luís Roberto Barroso ruled on January 30 that the federal government should remove all illegal miners from the seven Indigenous territories in the Amazon basin. Among the territories subject to the removal of invaders was Trincheira Bacajá.

In 2022, the supreme court recognized the Brazilian government had failed to respect Indigenous rights when it did not, in accordance with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, obtain prior, free, and informed consent from the Indigenous peoples in the area. As the first supreme court decision to rule on the prior consent of Belo Monte, it was a historic judgement. In his decision, justice Alexandre de Moraes affirmed “Ibama’s argument that the project is not located on Indigenous land, a view also held by the union, does not stand up to scrutiny [. . .] Although the project is not located entirely in Indigenous territory, its impact—which extends far beyond the project itself—clearly extends into Indigenous territories.”

When questioned by SUMAÚMA about Belo Monte’s role in the increased devastation of the forest, Norte Energia stated only that it wished to “clarify that the suppression of vegetation involved in the construction of the Belo Monte HPP (Hydro Power Plant) represents 0.04% of the total area of the Xingu River basin and 0.0045% of the legal Amazon region.” When asked about the delays in the construction of the territorial protection units intended to defend the Indigenous territories affected by the plant, the company stated that eight are in operation while another three, in the Ituna Itatá, Koatinemo and Cachoeira Seca Indigenous territories, “suffered delays due to security issues in those regions.” It also said that construction of the protection units in Ituna Itatá and Koatinemo began in October 2022, accompanied by Funai and Brazil’s National Security Force, but that it was still awaiting authorization to start work in Cachoeira Seca. The irony is hard to miss: the company argues that land conflicts on indigenous lands have prevented the construction of protection units which, according to environmental impact studies, should have been carried out before work on the plant began – precisely to avoid land conflicts.

How the majestic Xingu became Belo Monte’s personal water tank

The Volta Grande of the Xingu River is a stretch of roughly 130 kilometers of water that flows downstream of the city of Altamira. Here, the river takes a sharp 90-degree turn, forming what was once, before Belo Monte, a stunning landscape of islands, beaches, rocks, and floodplain forests. Canoes would carry people back and forth from the city to sell their ever-abundant surplus fish catches, as well as local products—above all cassava flour, a key food for many Amazonian communities. The Volta Grande region is also home to several ribeirinho and Indigenous communities: the three largest peoples of the demarcated, regulated territories are the Arara of Volta Grande, the Yudjá (Juruna) of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory, and the Xikrin of Trincheira Bacajá. Due to its distinctive environmental traits, the Volta Grande region was composed of a series of unique ecosystems that bred endemic species like the acari-zebra, as well as Indigenous and ribeirinho communities that, until Belo Monte, lived in harmony with the flood pulse (the annual rhythm of flooding and drought) of the Xingu River.

In 2015, this delicate equilibrium was broken, or cut, in the words of the residents of the Volta Grande region. In November of that year, Belo Monte received its operating license, and the installation of the company’s main dam, in Pimental, led to a string of tragic consequences, not only for the region’s ecological balance but also for the communities living there. The first was the slaughter of more than 55,000 fish (16 tons), according to Ibama’s calculations, observed in the first weeks after the dam was finished. Some had been crushed by the excessive force of water driven by the turbines. Others were left with no oxygen, trapped in pools of warm water in the Volta Grande region, from where large quantities of water were diverted. This took place during the species’ reproductive period, when they were looking for places to feed and spawn. For this carnage, Ibama fined Norte Energia 27 million reais, roughly USD 5 million.

Nevertheless, another 23,260 fish died the following year during what should have been the Xingu River flood season. In 2021, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office estimated Belo Monte caused the death of over 85,000 specimens or about 24 metric tons of fish from November 2015 to December 2018, based on infraction notices issued by Ibama. These fines may reach a total of 70 million reais, around USD 13.5 million; a suit involving collection of the fines has been filed with the Federal Court in Altamira.

HUNDREDS OF DEAD TREES MAKE THE BELO MONTE RESERVOIR A GRAVEYARD FOR NATURE. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA/ SUMAÚMA (JANUARY 2023)

In the early evening of January 26, 2016, a torrent of waters unleashed by the Belo Monte plant swept through the Volta Grande do Xingu without warning, carrying away the boats, motors, fishing tackle, clothing, dishes, and other belongings that traditional communities have long had the habit of leaving on the riverbanks. It was like an extreme weather event, increasingly common as the climate crisis worsens. In this case, however, the culprit was the sudden discharge of water by Belo Monte plant managers without forewarning.

The damage was great but the subsequent fear greater. Locals were now afraid of the riverbank and began telling their children not to bathe or play in the water. There were reports of clouds of fierce Amazon mosquitoes forcing families to eat meals on their beds under mosquito netting. Once familiar waters became unpredictable, sometimes rising, sometimes falling. The Xingu, father and mother to these Indigenous and traditional peoples, was now a stranger. There were so many overwhelming changes that in the Volta Grande region, 2016 is still called “the year of the end of the world.”

The expression “end of the world” might sound like hyperbole, but for communities whose ways of life were in total harmony with the annual cycle of flooding, high water, low water, and drought that characterizes the flood pulse of large Amazon rivers, this is an accurate description. Communities there began living in a permanent state of drought because 70% of the water that used to run through the Volta Grande were diverted to drive the dam’s hydroelectric turbines. During the Amazonian summer, from May to October, when waters are low and the Xingu’s historical flow rate used to be 2,000 cubic meters per second (m3/s), the change is not felt as much. But in the winter, from November to April, when waters have historically run high, an average of 20,000 m3/s used to surge down the river, sometimes even 25,000 m3/s. This was when fish would enter the Volta Grande in search of countless refuges in riverside forests that gradually flooded and gave access to abundant fruit. Hidden away in recesses of islands and riverbanks and thus protected from predators, the fish found ideal spots to spawn, places known as piracemas.

“Generally, when we talk about piracemas in Brazil, we’re talking about fish heading upstream to spawn at the headwaters, a strategy used so younger fish can spread out along the course of the river. In the case of the Xingu, there are lots of rapids and waterfalls along this stretch. The fish are always moving, and when ribeirinhos talk about piracemas, they’re really talking about both space and time. It’s the moment when the waters rise and the fish swim upstream, not toward the headwaters but in search of these recently flooded areas, perfect for spawning,” said the scientist Jansen Zuanon. Today, most piracemas no longer afford this type of refuge, which means species in the region have practically been unable to breed since the Pimental dam definitively diverted the Xingu away from the Volta Grande.

To lessen the impact of this reduced flow, the main mitigation measure proposed by Norte Energia was a water management system called the “Consensus Hydrograph”—a misnomer since the plan never represented any consensus. On the contrary, neither the affected populations nor the scientists who advise the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office ever agreed agreed to the unequal division of water, which would be incompatible with the ways of life of both humans and nonhumans. The plant’s operating license stipulated the release of 4,000 m3/s one year and 8,000 m3/s the next, which would subject all beings living in the region to an unsustainable level of water stress.

FISHERMEN DRAG A BOAT OVER THE ROCKS TO CROSS A RIVER THAT HAS RUN DRY BECAUSE BELO MONTE USES THE XINGU RIVER AS ITS OWN PRIVATE WATER TANK. PHOTO: LALO DE ALMEIDA/FOLHAPRESS (SEPTEMBER 2022)

When the Prosecutor’s Office investigated licensing documents for Belo Monte, it found that Ibama technical specialists had been diametrically opposed to Norte Energia’s proposed water management plan. In 2009, prior to preliminary licensing, Ibama warned in a technical report that the proposed water level would not be enough to sustain life. The report states: “It is not clear if there will be minimum conditions for the reproduction and food supply of ichthyofauna (fish), chelonians (turtles, tortoise and terrapins), and aquatic birds, nor is it clear whether the system can stand this amount of stress in the medium and long terms. The proposed Consensus Hydrograph in no way guarantees the sustainability of the ecosystem or the recruitment of most species that depend on the flood pulse, and this could have critical negative impacts, even compromising food supplies and the ways of life of people living along the Volta Grande.” But when the license was issued, those in charge at the agency, then headed by Roberto Messias Franco, completely ignored their own specialists. The company’s proposal was accepted in full, a political decision likewise embraced by the Environment Ministry, then led by Carlos Minc.

During the years of the construction and operation of the hydro plant, the suggested water plan, called “Hydrograph B,” was to discharge 8,000 m3/s into the Volta Grande during the wet season. This meant that when the Xingu reached maximum flow, at 20,000 m3/s, most of the water would be directed to the plant’s turbines, while the region’s ecosystems and communities would remain under dry conditions, receiving 8,000 m3/s at most. According to the geologist André Sawakuchi, dividing the waters like this was an inversion of priorities: between biodiversity and power generation, a decision was made to sacrifice biodiversity along with the region’s floodplain forests—tantamount to deforestation.

This finding is not trivial and has legal implications, since the pillar of Brazil’s constitutional law on the environment is the principle of precaution, which dictates that environmental protection should always be prioritized. This interpretation was confirmed in a technical report issued by Ibama in December 2019. The agency’s technical team attested to the seriousness of the impacts on the Volta Grande and said the region could not be held to only 8,000 m3/s, at least not until there were guarantees that local communities and ecosystems could survive the artificial water levels.

In its technical report 133/2019, Ibama stated Hydrographs A and B were “unviable,” called for additional studies, and moved to enforce the so-called provisional hydrograph, which would release slightly more water than earlier management plans, until further studies could determine how much water is needed to ensure the seasonal flooding of riverbank forests, food supplies, and the reproduction of aquatic fauna, all crucial to the entire region’s survival and to the continuation of Indigenous and ribeirinho communities’ ways of life. The interim plan was in effect from April 2020 through February 2021, but the relief was short-lived. Once again—as so often the case with the Belo Monte licensing process—those in charge failed to abide by the conclusions of the technical team.

In February 2021, Eduardo Bim, then president of Ibama, approved the implementation of Hydrograph B until further studies could be completed. In exchange for the water that would guarantee life, Ibama signed an Environmental Commitment Agreement with Norte Energia, which specified a series of additional mitigation measures and compensation for Volta Grande communities. This decision left the Volta Grande without enough water for another two years. The supplementary studies were submitted, rejected, redone, and, after all this back-and-forth, finally concluded in 2022. Ibama’s technical team is expected to issue a final report in the coming weeks.

At the same time, the dilemma about how to divide the Xingu waters reached the courts. The Federal Justice in Altamira and the Federal Regional Court of the First Region ruled in favor of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office and ordered Belo Monte to release enough water to ensure the survival of the Volta Grande, but the president of the regional court, Ítalo Mendes, suspended the ruling. The Public Prosecutor’s Office has appealed Mendes’ decision, but the case remains stalled. Today, the volume of water impounded by the power plant hinders the survival of much of the region’s aquatic fauna and seriously jeopardizes the lives of traditional populations.

Norte Energia told SUMAÚMA that “statements about the slaughter of fish and fines are untrue and the matter is being discussed in court to obtain proof of the true facts.” The company is referring to two lawsuits brought by the Federal Public Prosecutor, which accuse the company of causing both the death of fish and damage to fishing communities. The lawsuits are pending in the Federal Court of Altamira.

Of the artificial flood that swept through Volta Grande do Xingu in January 2016, the company said only that “upon learning about the incident at the time, it provided a response to both Ibama and the communities, and the appropriate measures were taken.” Despite being asked specifically about compensation for residents, it did not provide details about what these measures were.

Finally, regarding the diversion of water from Volta Grande, the company stated that it “did not establish nor define the operational hydrographs of the plant”, and that this decision came from Ibama, “based on technical and ecological studies, aimed at ensuring the maintenance of the quality of water, the conservation of ichthyofauna, alluvial vegetation, turtles, and of fishing and navigation, in addition to the ways of life of the population in the region.” According to Norte Energia, it is “unaware of truly scientific data on the damage and its causes, and has no knowledge of a humanitarian crisis affecting the population in its area of direct influence, caused by the operation of the plant.”

Ibama, meanwhile, said that a team of technical specialists is currently assessing the situation in Volta Grande do Xingu to “enable a decision by the licensing agency on the applicability of the ‘Consensus Hydrogram’ [Ibama’s quotation marks], proposed in the Environmental Impact Study”. The specialists are evaluating the complementary studies delivered by the Belo Monte concessionaire on the dynamics of flooding in the region, its ecosystems and the socioeconomic impacts on residents. Ibama did not say, however, whether there is a forecasted completion date for such analyses.

The last chance for the Xingu—and its peoples

Most of the rights enjoyed by the many thousands of people who have been hit by Belo Monte were very hard won. Had Indigenous and ribeirinho communities along the Volta Grande not protested, there would be no free, public system for transferring boats from one side of the river to the other and no bridge over the diversion canal, which provides road access to the Xingu in the region of the Paquiçamba Indigenous Territory. Had residents in the Independente I and Independente II housing developments not made their voices heard, they never would have been recognized as affected by the dam and therefore never resettled; perhaps they simply would have been left with nothing but homes that are now underwater. Had the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, and ribeirinhos not made their voices heard, their rights as traditional communities would not have been taken into account and Ibama would not have recognized the ribeirinho territory. Had the Indigenous who live in the city not put up a fight, a development project more suited to their way of life, the neighborhood of Tavaquara, would not have been built.

This environmental and humanitarian disaster on the Volta Grande do Xingu is yet another chapter in which the mobilization of those impacted by the dam may prove crucial. In August 2022, the first results of a joint study by Indigenous, ribeirinho, and academic researchers were submitted to Ibama, offering an independent technical evaluation of information furnished by Norte Energia. The technical report issued by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office proposes a series of measures that, if adopted, might save the region’s ecosystems and communities.

The ribeirinhos have optimistically dubbed their proposal the “Piracemas Hydrograph.” Their idea is to enforce a temporary water management plan tailored to the Volta Grande, while additional studies are conducted and a multidisciplinary group comprising representatives of Indigenous and ribeirinho communities can be formed to draw up a socio-ecological water plan for the Volta Grande, one that will guarantee the viability of the region’s ecosystems and the lifeways of its peoples, as well as power production by Belo Monte. While these studies are being carried out, residents and scientists have asked Ibama to respect the river’s natural ebb and flow.

The logic that has prevailed at Belo Monte ever since the plant was designed must be inverted, replaced by an attitude that protects the region’s socio-cultural and ecological wealth. “So far, they’ve calculated how much water Belo Monte needs to produce energy, and only what is left over goes to the Volta Grande,” says the biologist André Sawakuchi. “If this project really wanted to reduce biodiversity loss, it would have to reverse this logic. They’d have to consider the minimum quantity of water needed to sustain the region’s ecosystems and then the surplus would be used to generate energy.” In André’s opinion, the Xingu has a chance if Ibama and the government agree with the proposals of scientists, ribeirinhos, and the Indigenous. “In the area of the reservoir, the losses are already irreversible. In the Volta Grande, something can still be done,” he said.

There is no way to make reparations for Belo Monte’s impacts. They have already left their mark on more than one generation of human people and have destroyed millions of nonhuman lives, in addition to jeopardizing a way of life that is very much connected to the forest, with damages that go far beyond it. We know all too well that when nature is disturbed, the aftereffects are not circumscribed but can unleash a destructive chain reaction. Yet it is possible—and constitutionally mandatory—for the government to prevent future, possibly more destructive, impacts, and to finally respect the requirements that should always have governed the construction and operation of the hydropower plant.

It is not only the Volta Grande do Xingu that might stand a chance now, but also the legacy of Lula and the Workers’ Party in the Amazon.

Fact check: Plínio Lopes

Spell check (Portuguese): Elvira Gago

Translation into Spanish: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: James Young, Julia Sanches, and Diane Whitty

Photography editing: Marcelo Aguilar, Mariana Greif and Pablo Albarenga

CARLOS EDUARDO DE ALMEIDA, ON HIS BIKE, CARRIES AN EMPTY WATER CONTAINER FOR HIS MOTHER IN THE LARANJEIRAS HOUSING DEVELOPMENT, IN ALTAMIRA, PARÁ. PHOTO: SOLL SOUSA / SUMAÚMA