After burying so many people in Medicilândia, a municipality in Pará state located along the Trans-Amazonian highway, gravedigger Adilson Fagundes picked up a notebook and committed the numbers to paper one day. “I counted: there were a hundred some graves of anonymous people who came from elsewhere to die here,” he wrote. “There are more today.” According to Adilson, it used to be gunmen who dumped bodies there in the dead of the night, almost always victims shot to death because of land conflicts. Now it’s drug traffickers. In Medicilândia, the cemetery walls are graffitied with the names of criminal factions from Southeast Brazil that are also active in the Brazilian Amazon—for example, Red Command, based down south, and Class A Command, which first appeared in Altamira and is an ally of First Capital Command, another southern faction.

Like the gravedigger, Medicilândia wakes up early. At 6:30, in the dense morning fog, shopkeepers roll up their heavy doors and the streets fill with motorbikes. By 7 o’clock, it’s wall-to-wall motorcyclists, transporting men, women, children, teenagers, and the elderly. Nobody wears a helmet; the Military Police pass by and ignore them. According to the National Transportation Department, there are around 7,500 vehicles in Medicilândia: 935 pickups, 1,011 cars, and nearly 5,000 motorcycles. A dusty film gradually settles on the asphalt, and an orangish powder covers sidewalks, streets, and the household appliances on display outside storefronts. By 8 o’clock, the sun is scorching hot.

Population 27,000, Medicilândia is home to 218,779 head of beef cattle, honored with a statue at the entrance to town (left, background)

This Trans-Amazonian city was named after dictator Emílio Garrastazu Médici (1905-1985), who was in power from 1969 to 1974 and whose government was responsible for kidnapping, torturing, and executing more civilians than any administration during the dictatorship (1964-1985). Medicilândia has two main avenues, one named President Médici. The city has a population of 27,000 people (only 6.6% of them have work), 218,779 cattle, 4,560 horses, 1,502 sheep, 1,399 pigs, and 97 goats. It is the destination of people who came here to die, as the grave digger tells us, but also of people who stayed on after they killed. And of Darci Alves Pereira, 56, the confessed murderer of Chico Mendes, environmentalist, trade union leader, and rubber tapper—a crime that put the Amazonian state of Acre in the international spotlight when it took place in 1988.

Thirty-four years ago, Darci and his father, the land grabber Darly Alves—accused of being the mastermind behind the killing—were sentenced to 19 years in prison. They each spent just over six years behind bars. Since then, Darci has lived in Medicilândia under a false name—Daniel Dorzila de Oliveira (a name he borrowed from a relative, currently precandidate for mayor of Epitaciolândia, in Acre).

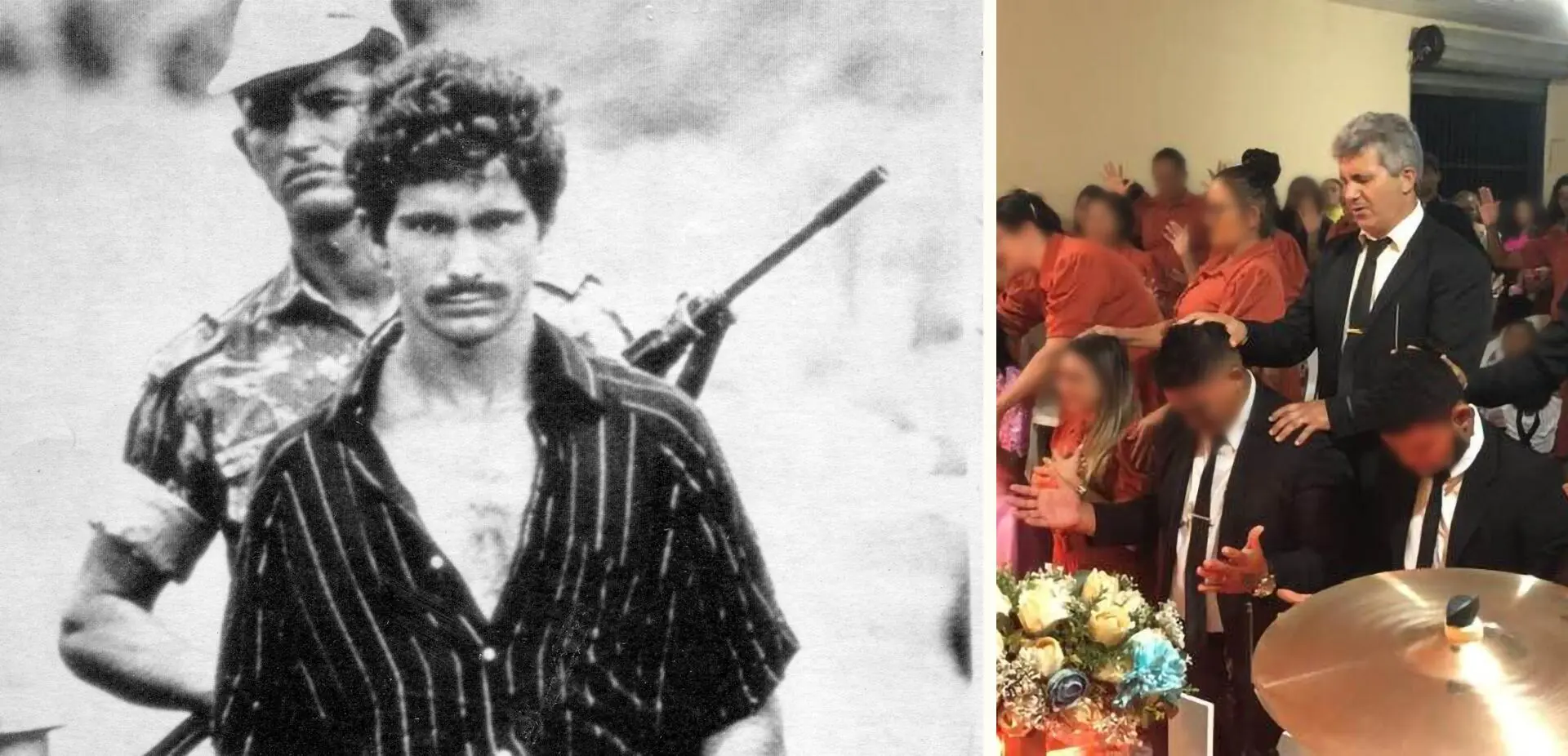

After starting an Evangelical church, Darci began introducing himself as “Pastor Daniel,” and now he is trying to make his way into politics. A precandidate for city council member and former municipal president of far-right Jair Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party, he was removed from office in February after the site ((o))eco revealed that the head of the Liberal Party in Medicilândia and the confessed murderer of the greatest Brazilian environmentalist of all times were one and the same person. On April 5, Darci was expelled from the party.

In this report, SUMAÚMA retraces Darci’s arrival to Medicilândia and his life in the town. The man who in 1988 admitted to killing Chico Mendes has grown rich off cattle, cacao, and real estate. And he wants to get into politics in a city where Bolsonaro garnered 67.3% of the votes in 2022. Lula, 32.7%.

After his arrest, Darci (left) was born again. In Medicilândia, he became a pastor and started his own church. Photos: Josemar Gonçalves/Agência O Globo & Reproduced from Facebook

THE TOWN

At the entrance to the town, a large archway displays the phrase “I love Medicilândia,” with a red heart in place of the verb. The city came into being when dictator Emílio Garrastazu Médici launched the National Integration Plan in 1971, a series of “pharaonic public works projects,” as journalists called them at the time, whose first priority was construction of the Trans-Amazonian highway. In 1973, houses started going up in a village designed to lodge some of the thousands of Brazilians who migrated to the region from the Northeast.

Médici used the National Integration Program to distract attention from the fact that the military was torturing, killing, and disposing of the bodies of its opponents. It wasn’t until more than 40 years later that a CIA memorandum dug up by Professor Matias Spektor, of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, revealed that 104 prisoners had been summarily executed on Army premises during Médici’s last year in office, 1973, the same year work began on the village of Medicilândia, reincorporated as a city in 1988.

The town sprang up in the 1970s, designed to house some of the thousands of Northeasterners who came to the region to lay the Trans-Amazonian highway

THE CRIME

Likewise in 1988, at 6:30 in the evening on Thursday, December 22, Francisco Alves Mendes Filho—the environmentalist and rubber tapper leader Chico Mendes—was playing dominoes with a corporal and a private from the Military Police, security guards provided by the Acre state government. Game ended, he got up and headed to the backyard shower at his home in the town of Xapuri, 116 miles from the state capital, Rio Branco. Darci, then 21, was hiding behind a coconut tree, armed with a 12-gauge shotgun, as he was to confess four days later. At 6:45 PM, Chico Mendes was hit by 42 lead pellets in the right side of his chest.

The news went round the world. Three years earlier, Chico Mendes had led the National Meeting of Rubber Tappers and helped found the Union of Forest Peoples, an unprecedented alliance of rubber tappers, Indigenous peoples, Brazil nut harvesters, and Ribeirinhos (members of traditional forest communities who live in close relationship with the Amazon’s rivers). Chico united people who wanted the forest to remain standing—in opposition to the deforesters united in the Democratic Ruralist Union. As a rubber tapper and trade unionist, he denounced the destruction of the Amazon at the United Nations.

Chico Mendes was killed on his way to the backyard shower at his home in Xapuri, Acre. The house is now a museum. Photos: Homero Sérgio/Folhapress & Odair Leal/Folhapress

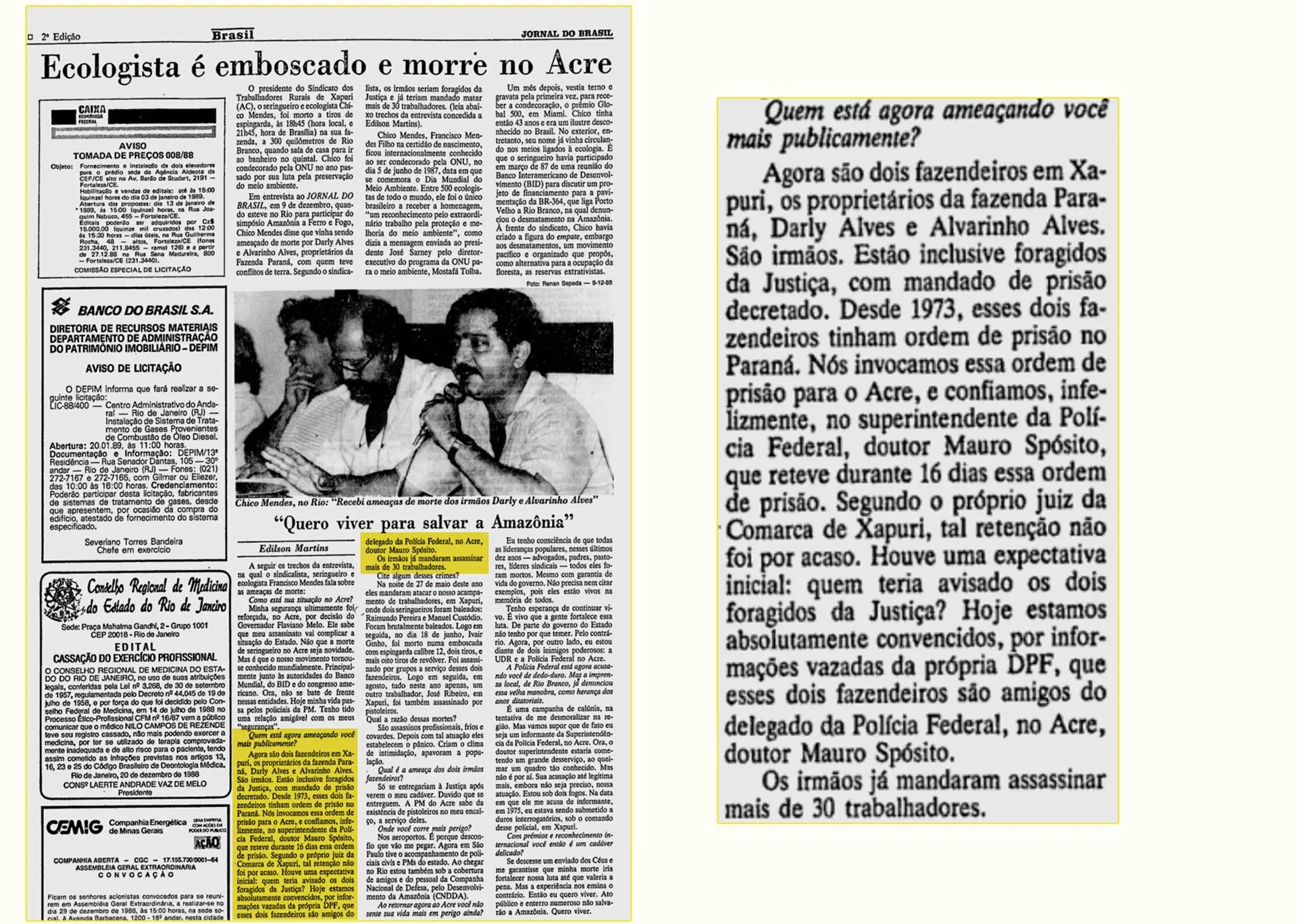

Thirteen days before he was murdered, Chico Mendes had foretold his impending assassination. On December 9, 1988, in an interview with the newspaper Jornal do Brasil, Chico said Darly Alves and his older brother, Alvarino, had threatened to kill him. Chico sent letters to the authorities notifying them of the fact. After the government expropriated the Cachoeira rubber plantation—which Darly claimed to own and where he intended to raise cattle—the land grabber began targeting Chico. Three months before he was killed, the trade union leader tracked down Darly’s criminal record in the southern state of Paraná and forwarded it to Mauro Sposito, then Federal Police commissioner in Acre. “I was a correspondent for Estadão in Acre. I did a story on Chico, saying he was the target of a plot,” says 62-year-old Altino Machado, a reporter from Acre who covered the case.

Sposito, now retired, was coordinator of special border operations and Federal Police commissioner in Amazonas state for eight years. When asked by SUMAÚMA if he was close to Darly and other cattle ranchers, he said: “I wasn’t at all close [to Darly]. […] That’s idle talk.” He claims that back then he received a judicial letter from Bishop Moacyr Grechi, a friend of Chico Mendes, registering a complaint about Darly. “It was addressed to the judge in Xapuri,” the commissioner says. “I said, ‘Look, I can’t do anything about it because it’s addressed to the judge in Xapuri.’” Sposito claims he saw Darly only once.

Four days after the murder, Darci turned himself in. “The police don’t believe he’s the perpetrator of the crime. They think he gave himself up to get the police off his father’s back,” reported the front page of Jornal do Brasil the following day. During the reenactment of the crime done at the time (which took four days and resulted in a six-hour video), Darci furnished details: the position he was in (seated), whether he felt nervous (“I did feel nervous, yessir”), the church bell he heard while hiding, the light hitting Chico’s face, the lantern the victim was holding. The police called in experts from Campinas State University and members of the São Paulo police force to participate in the investigation, which the courts considered “impeccable,” as journalist Zuenir Ventura wrote in his book Chico Mendes – Crime e Castigo (Chico Mendes: crime and punishment). “I did it myself. The guy was always threatening my father. Every day, in the press, on the radio. Every day,” the confessed murderer said at the time. “I fired the gun and ran off.”

Speaking to SUMAÚMA, Darci denied killing Chico Mendes and promised to reveal “the truth” in a book. “I didn’t kill Chico Mendes. I didn’t,” he says. “I can assure you with absolute certainty it wasn’t me who pulled the trigger. I presented myself as the criminal to try to confuse the authorities. At the time, someone ended up talking me into it.” Darci didn’t go into details. “It’s my dream to write a book in the future. A broader, more comprehensive view. If you want to write the book, contact me later. It’d probably be a big hit and maybe even become a movie.” Asked if he knew another perpetrator, he laughed. “That’s the question that won’t go away, right?” he said. “Maybe I could go even further.”

The December 23, 1988, issue of Jornal do Brasil, reporting the murder of Chico Mendes. Excerpt of his interview days before, in which he told of receiving death threats

THE WITNESS

Darci’s 1988 confession gained credibility with the testimony of Genésio Ferreira da Silva, a key witness in the case. From the ages of 7 to 13, Genésio lived on Paraná Ranch, in the vicinity of Xapuri, where Chico Mendes’s murder plot was hatched. He lived there with his sister, who was married to Oloci, Darci’s half-brother, by way of their father. In his book Pássaro sem Rumo: uma Amazônia Chamada Genésio (Aimless bird: an Amazon called Genésio), published in 2015 by the Vladimir Herzog Institute, he revealed what he knew of the case.

According to Genésio, Darly used to walk around with a .38 revolver on his belt. Feared, with a reputation as a gunman and a Casanova, he lived with four women. He had a love affair with a prostitute in Paraná and then took their son, Darci, to Acre, where the boy was raised by Natalina, one of Darly’s girlfriends. “He was mistreated by the old Natalina and the three older kids, Oloci, Darlizinho, and Vera, who shared the same father,” Genésio says in the book. “He felt humiliated. […] He was a nervous, rebellious kind of person. […] That’s why he was defiant and dangerous, really dangerous, and he considered himself the family bastard.”

Genésio soon got to know Darci’s dark side. “Darci, Oloci, Amadeu, and Serginho [Darci’s cousins] had murdered two Bolivian students who were carrying roughly one to two kilos of pure cocaine in their bags. They did the killing at the request of the rancher Darly,” he wrote. Genésio witnessed the day the Bolivians passed through, never to return. He heard four gunshots. Then he saw Darci with a package in his hand, full of white powder. “Today I know it was cocaine,” Genésio told SUMAÚMA. Now 56, he spent some of the intervening years at an alcohol rehab clinic.

Genésio Ferreira da Silva, the only witness to Chico Mendes’s murder, was forced to flee his state or risk being killed. Photo: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real

When he spoke to SUMAÚMA, Darci was evasive: “I have no clue where you’re going with this because I don’t have anything to do with it, with Bolivians. I didn’t know those Bolivians, only heard about them. They opened a case about it, took my statement, but I wasn’t involved.”

Genésio also remembers hearing about it when Darly announced he was going to kill Chico Mendes. “He [Darly] said Chico Mendes wouldn’t live another year. Before killing him, he said he was going to go ask Chico Mendes to be his cumpadre [godfather to his child or groomsman] just to kill him. He was going to call Chico Mendes there to be his cumpadre and then kill him,” Genésio said in an interview to Zuenir, in 1988. He repeated to SUMAÚMA everything he had said at the time and later wrote in his book, detailing how Chico Mendes’s murder was plotted.

FAMILY OF KILLERS

Darly’s treacherous methods followed the example set by the family patriarch, Sebastião Alves. Darly’s father was a feared farmer in Minas Gerais in the 1950s. In 1958, Darly and two of his brothers, along with their father Sebastião, killed a cattle drover and his 15-year-old son in the interior of the state. Indicted by the Public Prosecutor’s Office in 1963, the Alves fled to Paraná.

There, they killed some more. In 1969, the businessman Ângelo Urizzi, an Austrian-born Jew involved in a land dispute with Darly, was killed by a gunman. In 1973, ngelo’s son, Acir Urizzi, was murdered. In 1974, Darly fled Paraná for Xapuri. More than 20 years later, he was found guilty of murdering Acir Urizzi. ngelo’s death went unpunished.

It was the paperwork on these crimes that Chico Mendes had located in hopes of seeing Darly arrested in Acre. But it was no use. In December 1988, Genésio, the key witness, overheard the following exchange, as he recounted in his book: “So, is everything ready to end Chico’s life?” Darly asked Darci and his cousin Serginho. “Yessir,” Serginho said. “And the ambush,” Darly went on, “has it all been planned out, like I asked?” “Everything’s just like you asked,” Darci replied. In his book, Genésio claims Darci was given 150 head of cattle as a reward for the murder.

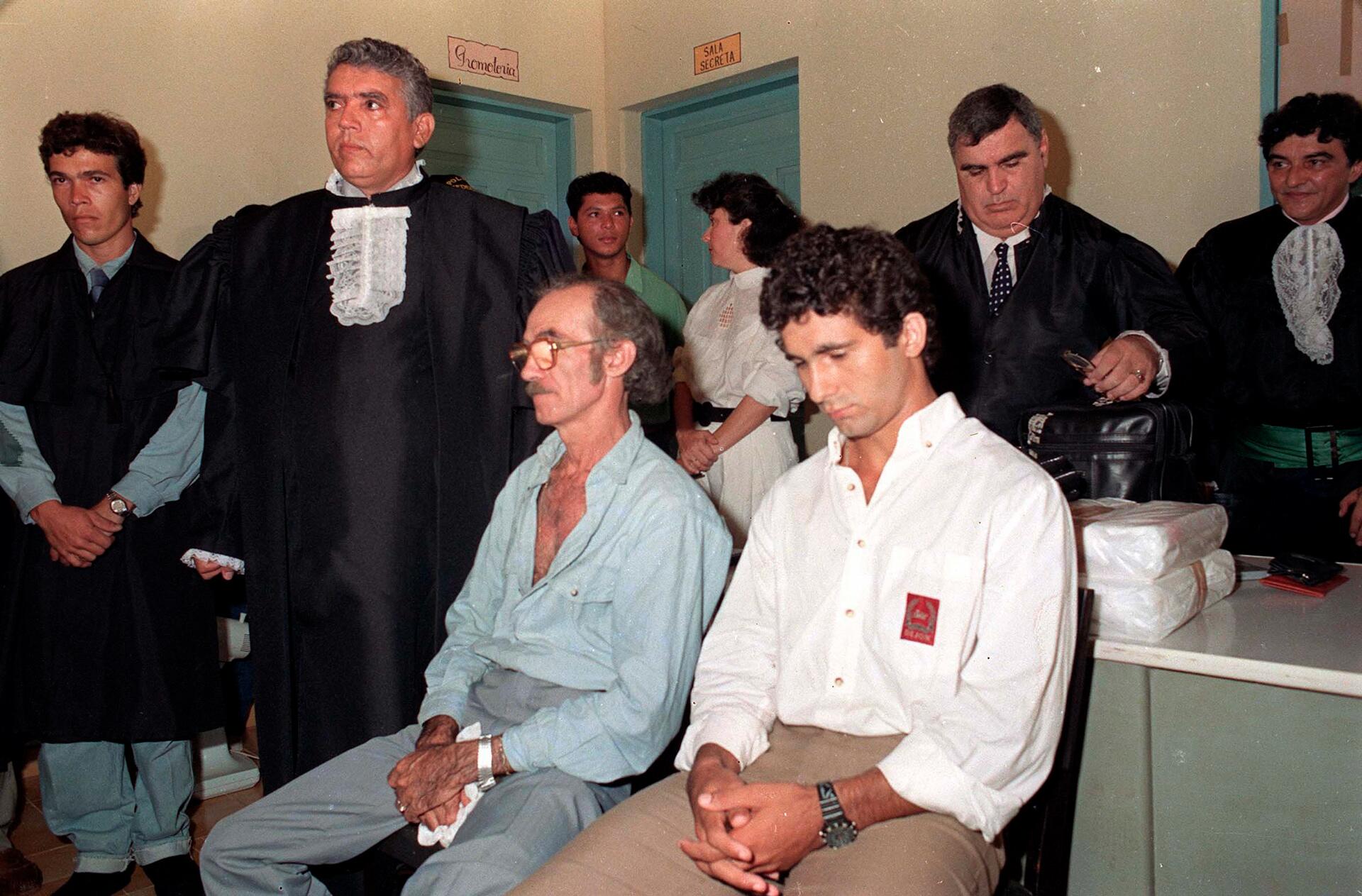

Dois anos após o crime, Darly (à esq.) e Darci foram condenados a 19 anos de prisão. Foto: Antônio Gaudério/Folhapress

After confessing, Darci changed his statement twice: first, he said he wasn’t in Xapuri on the day of the crime; then he denied doing it at all. In 1990, Darly and Darci were sentenced to 19 years in prison for the murder of the rubber tapper leader.

PRISON AND ESCAPE

In February 1993, after sawing through bars and escaping prison in Acre, Darci and Darly took refuge in the region of Medicilândia, where Darly introduced himself as João Mato Grosso and Darci became Daniel.

“Everybody knew him [Darly] as João Mato Grosso, who came from Mato Grosso and not Acre, and Darci was Daniel,” says Ademir Venturin, CEO of Cacauway, a chocolate factory with ties to the cacao producers co-operative in Medicilândia. Raimundo Xavier, president of the municipal Union of Rural Workers, remembers when Darci arrived in the region. “It was him and his father, Darly, known as João Mato Grosso. Nobody knew his name right,” says Raimundo. “He went around buying up land there.”

Darci admitted to SUMAÚMA that he had used a false name and documents. “This name Daniel, nickname Daniel, was when I left Acre. I’d escaped from prison and a bro… a relative of mine provided me with his document so I could get out. I came here with this name,” says Darci. “I didn’t want to tell folks to quit calling me that. But all my documents are Darci Alves Pereira. Around here, if you ask for Darci, not many folks know who Darci is.”

Darci arrived in Medicilândia under the name Daniel. He posts right-wing messages and videos of his church services on social media. Photo: Reproduced from Facebook

In June 1996, federal police arrested Darly in Medicilândia. Darci fled. He was captured five months later in Paraná, on the border with Paraguay. Father and son served the rest of their time in Brasilia, until Darly got out on home detention and Darci went to semi-detention, in 1999.

Darly headed to Acre. Now 88, he lives in a house in Rio Branco. His family is rich. They raise cattle and tambaqui fish on Paraná Ranch.

Darci returned to Medicilândia and started becoming someone else.

PASTOR DANIEL

Leaving urban Medicilândia behind, the pavement of the Trans-Amazonian highway gives way to a potholed road, unpassable in the rain. About 28 miles from downtown, right across from an Indigenous territory and a base of Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency Funai, lies the area known as “Kilometer 130 marker,” or Travessão. Ten miles off the highway—after four streams, two Evangelical churches, and a dozen small wooden houses—a large masonry building with high ceilings and solar roof panels stands on a thousand-acre plot of land. A Brazilian flag hangs on the porch. In one corner, a security camera and a small sign reading “Fierce dog.” In the yard sits a burgundy 4X4 pickup with a Jair Bolsonaro bumper sticker. This is Darci’s home.

The Trans-Amazonian highway uprooted trees and animals to make room for pastures. It also brought land theft and the eviction of Ribeirinhos and Indigenous peoples

“Travessão has a reputation for hiding people who are no good,” says a local resident who asked not to be identified. One of the landowners, says the resident, is Regivaldo Galvão, sentenced to 25 years in prison for ordering the murder of U.S. missionary Dorothy Stang in 2005. “If you poke around Travessão, you’ll find a lot of shit here.”

In 2018, according to neighbors, Darci started an Evangelical church called Missionaries of the Last Hour, an extension of the Assembly of God. “He used to be Catholic. After he was arrested, he opted for another religion and became a pastor,” says Venturin, from the cacao co-op. Darci built a chapel and started taking followers to rivers to baptize them. “People believed in his recovery, in his sanctification,” another neighbor says. “But it didn’t last long. Just like he went up, he came down.”

The faithful began leaving his church. “When they saw how he treated people, his arrogance, his economic power, they started trickling out, until the last one left,” a resident recalls. “They saw he wasn’t a pastor.” The church closed its doors. Today, Darci is setting up a new religious community in Altamira, a regional hub along the Trans-Amazonian highway, 53 miles from Medicilândia. “He wears a pastor’s shirt, Bible under his arm, but we know his heart isn’t… His environmental attitudes don’t show him protecting the Amazon.”

Periodically, Darci leads Evangelical services in Acre, on the same ranch where they plotted to kill Chico Mendes.

Brasil Novo, a municipality next to Medicilândia, will also have a statue honoring beef cattle now. Pastureland shares space with cacao trees here

Darci lives with his wife, Deusimar Vidal, and an underage son. Four siblings of his, Darly’s children, live nearby. There are 200 head of cattle, some tractors and other machinery, and 60,000 cacao trees on the land, where at least six sharecroppers work. On the national environmental registry of rural properties, a self-reported electronic database called CAR, the land is in Deusimar’s name and is said to be located in Uruará. There is no record of the property at the municipality’s registry office. At the registry office in Medicilândia, a clerk said they had documents in the name of Deusimar but didn’t inform the location of the property. Darci claims he bought the land legally. “We didn’t steal or invade anybody’s land. It was financed. Public deed, registration, written land record—I’m the only one here [Travessão] who has them. I paid off my debt to Incra [Brazil’s agrarian reform agency] at the time,” he told SUMAÚMA.

At least five of Darci’s relatives appear on the list of environmental offenders maintained by Ibama, Brazil’s environmental protection agency: his father Darly, brothers Oloci and Guinaldo, cousin Gentil, and wife Deusimar. In Uruará, a neighboring municipality of Medicilândia, Deusimar was fined BRL 900,000 (roughly USD 175,000) for clearing 452 acres of native forest. The environmental agency has declared the land off-limits to her. Medicilândia is one of the 25 most heavily deforested municipalities in Brazil.

Darci’s cacao beans go to multinationals that distribute them on the domestic market and abroad, through the U.S. company Cargill and the Belgian firm Barry Callebaut, the largest buyers of the product in Medicilândia. Cargill has blocked Darci as a direct supplier. “It was largely for political reasons that they didn’t want to [buy cacao from Darci] anymore,” says an ex-Cargill employee, formerly responsible for socio-environmental compliance at the company, who preferred not to be identified.

Asked by SUMAÚMA if Cargill had blocked him because of the Chico Mendes case, Darci replied: “I’ve got some paperwork there, but I don’t want to get into those details. We’ve got an application in to certify our cacao, but anyway… It’s up to them to do it…” Cargill said in a note that Darci was a supplier to the company for one month in 2018 and is now barred “because he does not conform to the [company’s] supplier policies.” Callebaut did not reply to a request for comment.

In 2022, Medicilândia’s cacao producers earned BRL 693 million, roughly USD 134 million. Planted area reached 108,726 acres, and 51,000 metric tons of beans were harvested, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Planted area for cacao is four times greater than the area for bananas, 441 times açai, and over 8,000 times guarana. The region’s fertile soil, the age of the cacao trees (older trees are more productive), recent droughts in the Ivory Coast, which is the world’s largest cacao producer, and the advance of witch’s broom in Bahia state have made Medicilândia cacao the most sought-after in the world and made the city the biggest cacao producer in Brazil.

An old sugar factory near a cacao plantation: Medicilândia is known as the cacao capital of Brazil

In 2020, Senator Zequinha Marinho (Podemos party, Pará), an ally of Jair Bolsonaro, came up with the idea of proposing a bill to grant Medicilândia the title of “cacao capital of Brazil.” The parliamentarian is in favor of reducing the boundaries of the Cachoeira Seca Indigenous Territory, a measure of interest to loggers, landgrabbers, and ranchers. Darci posted photos on social media showing him with his arms around the shoulders of Marinho and other far-right members of congress. In a note to SUMAÚMA, Marinho’s press office said the senator is from a different party and that “there is no relationship with the gentleman [Darci] who is the subject of this press investigation.” As to Marinho’s proposals, the press office said the senator “fights for the interests of Pará.”

Darci is also interested in politics. In 2022, he and his wife went to Brasilia to meet with Bolsonaro in the “playpen”—a fenced-off area outside the presidential residence where the former president would meet with reporters and supporters. “I don’t agree with men marrying men, women marrying women,” said Darci, who joined the Liberal Party in February 2022.

After Lula’s election in 2022, Darci and Deusimar attended Bolsonaro-backed demonstrations in favor of a military coup. Their neighbors pointed out that Darci had sold a number of head of cattle around the time of the anti-democratic acts perpetrated on January 8 of that year. “He’s one of the sponsors of January 8,” a neighbor said. “They say he backed the pro-coup demonstrations with BRL 60,000 [USD 12,000]. Others say 30. Fact is, they sold a lot of cattle around then.” Darci denies it. “It’s a lie. I don’t know where you got that from… I wouldn’t do that. If I have to help someone, it’s for God’s work, not for these political matters. I would never do that.”

In early April, at the behest of the national president of the Liberal Party, Valdemar Costa Neto, Darci was booted from the party “due to his reprehensible personal conduct,” according to the minutes of the party meeting in Medicilândia that decided to remove him.

“Valdemar made a wrong decision,” says Darci. “I’m cleaner than him. If you look at my record today, I don’t have any cases out against me. He wants to keep me out of the party just because of my past, way back when? I’ve paid my dues to the Justice system, to society. Nothing keeps me from being an ordinary citizen. I have the right to participate, and society is the one to respond. How does Medicilândia society see me?” he asks.

Darci Alves Pereira was stripped of the presidency of the local chapter of the Liberal Party and expelled after his past came to light. Photo: Reproduced from Instagram

Fearfully, according to a resident of Travessão. “We don’t like to talk about these folks much,” he says. “They’re scary. They’re powerful people. Daniel may not pick up a gun and fire it himself, but who’s on his side? Big shots, from here in Pará, in Acre, to Brasilia. They’re connected to all sorts of big shots.”

News of Darci’s eviction from the Liberal Party spread across WhatsApp groups in Medicilândia, and he left some of the groups. Residents boycotted his store that sells agrobusiness products.

Yet there are those who think Darci was treated unfairly by the Liberal Party. “He did what he did, he paid, and now he’s free,” says Walter Oliveira, president of the Rural Producers Association of Medicilândia. “I know him, he’s a good guy. He was at our assembly. He’s trying to get on with his life. If we believe there are human rights in this world, Darci is an example of this. He has the right to start his life over,” he argues. Politicians seem to feel the same. “I’ve been approached by several parties,” says Darci.

Those who continue to fight for the forest find it regrettable that Darci plays a part in Medicilândia life today. That’s how Angela Mendes, Chico Mendes’s daughter, feels. “Medicilândia doesn’t deserve someone who cowardly kills someone else. We have to rid politics of people with this kind of record.”

In a municipality that deforests to make way for cattle, Bolsonaro got 67.3% of the vote in the last elections

Report and text: Bruno Abbud

Photos: Christian Braga

Editing: Fernanda da Escóssia

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum