It was Monday, March 18, a crescent moon day, and even at high tide, it wasn’t easy to navigate the shallow rivers to Maracá-Jipioca Ecological Station, a mangrove-covered island midway along the coast of Amapá state. Elimarcos de Oliveira Sacramento—nickname Perereca (tree frog)—was at the helm of a motorized canoe, but the water depth kept the craft from living up to its Amazonian name: voadeira, or flyer. Elimarcos was born and raised on the rivers and in the mangrove forests that surround the municipality of Amapá, the departure point for access to the conservation unit.

“It’s a dead woman’s tide,” declared Perereca, who has provided services to the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation since 2007, both as an environmental agent and as a pilot of the outboard motorboats that are the only way to reach the island where Brazil records its highest tides: up to 40 feet.

Brazil’s highest tides—up to 40 feet—occur at the Maracá-Jipioca Ecological Station. Photo: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

Maré de morta—dead woman’s tide—is the poetic term people living on this coast use to refer to a neap tide, usually known in Portuguese as a maré morta—“dead tide.” Neap tides are associated with the moon’s first and third quarters, when the sun and moon are at right angles to each other and their gravitational pulls on the oceans partially cancel each other out. When this occurs, the difference between low and high tides is smaller. During new and full moons, when the two celestial bodies are aligned, their gravitational power combines to produce a greater tidal range, which is the difference between low and high tide. This is known as a spring tide.

Maracá Island lies in shallow coastal waters, which are characteristic of the entire area influenced by sediments discharged by the Amazon River. Shallow, but not calm. Even during a “dead woman’s tide,” when the sea doesn’t rise as much, the shallow depth of the waters means waves strike the coast harder. This phenomenon churns the sea around us as our small motorboat heads to the island.

If the winds on the coast are strong during a spring tide, the speed of the ocean waters increases, forming waves that travel miles up adjacent rivers. Known as a pororoca, the same phenomenon affects Inferno River, which cuts across Maracá Island and borders the main offices of the ecological station, a house on stilts threatened by the region’s habitual soil erosion—erosion that already consumed Jipioca, a much smaller island now visible solely in the name of the conservation unit. If pororoca tidal waves begin moving in, motorboat captains can do nothing but “get out of there as fast as possible, because the boat will capsize,” says Marivaldo de Oliveira Galvão, environmental agent at the conservation unit.

Iranildo Coutinho, geographer and environmental analyst, has been managing the Maracá-Jipioca Ecological Station for 11 years. He says he learned everything he knows about the region’s tides from local people, like Marivaldo and Perereca. “Tides define the rhythm of our work, of our life. They not only depend on the moon but also on the time of year, the winds, whether it’s winter or summer, on sediment discharge from the Amazon,” says Iranildo (in this area, the rainy winter season extends from December to July, while summer is from August to November). It’s no wonder traditional communities on the Amazon coast call the place where they live a maretório, or tidatorry: a portmanteau blending of tide and territory.

Iranildo is reminded of the objects that float in from the high seas, deposited in the channels on Maracá Island by the movement of tides, when the topic turns to potential oil drilling in Brazil’s equatorial margin—the coastline running from Amapá to Rio Grande do Norte, currently the only state where oil is produced offshore.

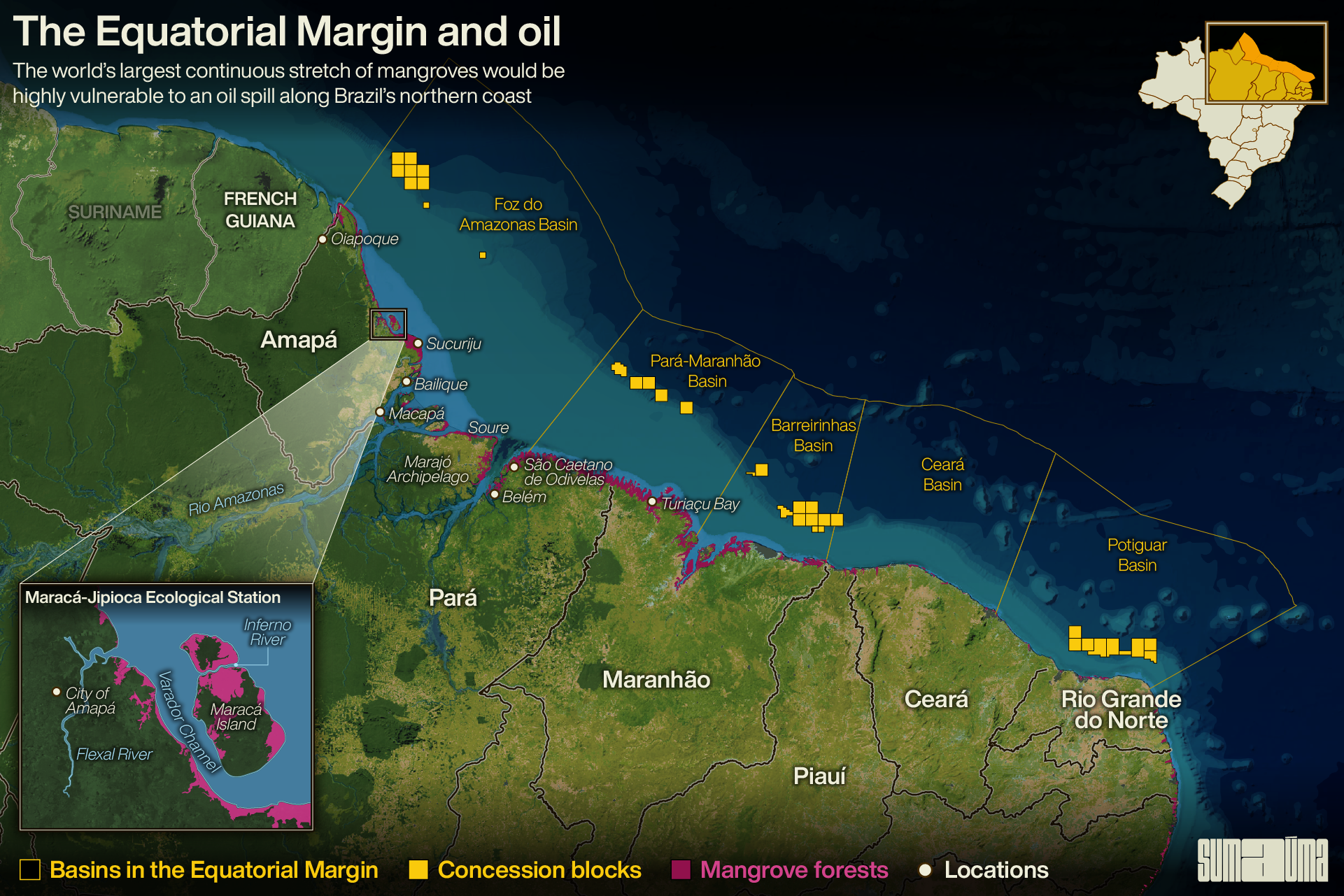

It was the case of the FZA-M-59 block, held by Brazil’s state-owned oil giant Petrobras, that sounded the alarm about the possible opening of a new frontier for this fossil fuel, the main culprit behind global heating. The block is located in deep waters of the Foz do Amazonas Basin, 99 miles from the town of Oiapoque, in far northern Amapá.

Brazil’s environmental protection agency Ibama had previously denied requests for drilling licenses in the equatorial margin, one in 2018, lodged by the French oil company Total, likewise in the Foz do Amazonas Basin, and another in 2021, by Petrobras itself, in the Barreirinhas Basin, off the coast of Maranhão. But neither of these requests unleashed the wave of political pressure felt by the environmental agency after its president, Rodrigo Agostinho, turned down Petrobras’s application for a license to explore for oil in the FZA-M-59 block, in May 2023.

In the document officializing his decision, Agostinho argued that there were no guarantees about an adequate accident response. He cited risks in the rescue plan for animals who might be affected by a spill, as well as unforeseen impacts on the three Indigenous territories in Oiapoque due to overflights by Petrobras aircraft.

Agostinho also quoted excerpts of an Ibama technical report from 2013, when the licensing process began for the FZA-M-59 block: “There are concerns about the region’s intense hydrodynamics, involving very strong currents and extremely large tidal ranges,” reads the text. The report also mentions the “unprecedented” scenario in which an oil spill might reach the coastlines of neighboring countries.

Petrobras has appealed the decision, proposing to reinforce its wildlife response plan and alleging it had already included provisions for a response to unprecedented accidents. However, the environmental agency has no deadline for issuing a final ruling.

Luís Takiyama, a chemist and environmental engineer, works with the coastal management program at the Amapá State Institute for Scientific and Technological Research. He explains that the water dynamics along Brazil’s equatorial margin are regulated by a number of interrelated factors. The main one is the North Brazil Current, which flows northwestward at an average of three knots (three times faster than the Brazil Current, predominant along the Southeast coast) and thus tends to carry material away from the shore. Another factor is the Atlantic trade winds, which blow from the northeast and east. These fast-moving winds flow perpendicular to the coast and tend to push material toward the continent. Then there are the marine currents running in the oceans depths, in some cases opposite to the North Current, although slower. Likewise factoring in are the tides and the outflow of the Amazon River, greater during the rainy season.

Marivaldo (left) works at the ecological station and is familiar with the tides. Photos: Alessandra Lameira/ICMBio & Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

Júlio and the university of the sea

Elimarcos and Marivaldo took members of the environmental network Greenpeace to Maracá Island this March, when the NGO team was visiting spots along the coast from Oiapoque to Belém, Pará. To avoid the risk of running aground on a sandbank, the Greenpeace ship Witness remained anchored offshore at an average water depth of 33 feet.

During the expedition, Luís Takiyama had technical responsibility for a Greenpeace-funded study to simulate the path of a hypothetical oil slick along the coast of the state. Seven drifters—a buoy-like instrument that emits GPS location signals—were launched as part of the experiment.

Drifters deployed by researcher Luís Takiyama to assess the effects of an oil spill were it to reach the coasts of Brazil and of neighboring countries. Photos: Enrico Marone/Greenpeace

There are several types of drifters, which can measure the effects of surface currents, tides, and winds, as well as deep-ocean currents. The study used the first type. Two were released closer to the coast, just after the Amazon River plume, where discharge from the river is deposited. Another two were launched near an area where oil blocks are set to be auctioned off. The remaining three were launched in the area of FZA-M-59 and other, contiguous Petrobras blocks.

The drifters that were launched closer to the coast soon reached both Marajó Island in the Amazon estuary and the region of Sucuriju, near Maracá Island, home to another conservation unit, Lago Piratuba Biological Reserve. The other five instruments were released in potential drilling areas and actually left Brazilian waters: three made it to the coasts of French Guiana, Suriname, and Guyana, the fourth traveled beyond Venezuela, and the fifth floated about the Caribbean, north of FZA-M-59. The drifters will be monitored until their GPS batteries die, which should be sometime in July.

The fact that the drifters released near the FZA-M-59 block journeyed beyond Brazil’s territorial sea—a finding that matches the results of studies submitted to the environmental agency Ibama by Petrobras—doesn’t make Júlio Teixeira Garcia, president of the Oiapoque Fishing Colony, rest any easier. “I know Cayenne, I know Kourou. The people on the other side are human beings,” he says, referring to the capital of French Guiana and the coastal town nearest the Spaceport where the European Space Agency launches rockets. Unlike Guyana and Suriname, there is no offshore oil exploration in French Guiana.

A fisher for 50 years, Júlio warns the tides in the region can “go bonkers.” Photo: Marcela Jeanjacque/Greenpeace

With the money he makes selling different species of catfish and hake, Júlio sent his three children to college. One is now a nurse, another a fishing engineer, and the youngest studied fish farming in Fortaleza, capital of Ceará. But Júlio’s alma mater is the sea. A fisherman since the age of 12, he says in his 50 years’ experience he has seen things he and his colleagues call “bonkers.” “When I was young, I spent more time at sea than on land. I’d be 10, 15, 20 days at sea, year round, winter and summer. When shark fishing was legal, I’d go over to the area of block 59 [FZA-M-59]. We’d work at anchor, so we’d know where the water was going and where it was coming from. It changes flow. Certain times of year, the tide ‘goes bonkers,’ as we say. At times it flows toward land; at times it flows out.”

Júlio recalls the famous case of the rocket launched from Kourou in 2014: after falling into the ocean more than 200 miles east of the FZA-M-59 block and some 250 miles off the Brazilian coast, debris reached Cape Orange National Park, which protects the mouth of the Oiapoque River. “If the tide ‘goes bonkers’ and something comes this way, we want to be sure we can get out of its path fast and not have it reach the coast,” he says.

Fishers are guaranteed an abundance of fish in this region thanks to the nearby mangroves, rivers, and the Great Amazon Reef . Photo: Enrico Marone/Greenpeace

Far beyond the FZA-M-59 block

Given that research of this kind generally takes years to complete, the study led by Luís Takiyama is a fairly limited experiment, but preliminary results are similar to findings from the North Coast Project. The latter project aimed to assess the vulnerability to an oil spill of the world’s largest continuous stretch of mangroves, covering an area of some 3,000 square miles from Amapá to Maranhão.

Mangrove forests are considered blue carbon ecosystems, which sequester and store more carbon dioxide than tropical forests themselves. As spawning and feeding grounds, they help sustain heavy fishing activities along the Amazon coast. In all, there are 594,747 registered artisanal fishers in the states of Amapá, Pará, and Maranhão, representing half of the nearly 1.2 million registered artisanal fishers in Brazil.

Dozens of researchers took part in the North Coast Project, funded by the oil concern Enauta. Under the project, 139 drifters were launched over the course of a year, from 2018 to 2019. There were six launch points: three near an Enauta block in the Pará-Maranhão Basin, one off the mouth of the Amazon River, one off the central coast of Amapá, and one in the position of the FZA-M-59 block.

At least one drifter came ashore every month. Of the 38 devices that did so, 24 landed on the Brazilian coast, 17 in Amapá and seven in Pará; the other 14 ended up on the shores of neighboring countries. Only one of the drifters released from the FZA-M-59 block made it to the continent, in Venezuela. As in the Greenpeace experiment, only drifters driven by surface currents and wind, and not by deep-ocean currents, were launched.

The study assessed mangrove vulnerability in four places, one in Amapá, two in Pará, and one in Maranhão. Researchers found the chances of oil reaching the coasts of Pará and Maranhão would be related to accidents in the Pará-Maranhão, Barreirinhas, Ceará, and, to a lesser extent, Potiguar (Rio Grande do Norte) basins. Probabilities ranged from 40% to 50% in the dry season and 20% to 40% in the rainy season, depending on the location.

The mouth of the Oiapoque River, which separates Brazil from French Guiana, is protected by a national park. Photo: Enrico Marone/Greenpeace

The risk was greater in the region of Sucuriju, in Amapá, where the same “hyper-tides” occur as on Maracá Island. The probability of an oil slick spreading to any of these places is highest in Sucuriju, as much as 80% in the dry season. The oil would come primarily from areas of the Foz do Amazonas Basin closer to the coast than the FZA-M-59 block, but also from basins to the east. “That’s why the issue of oil exploration in the equatorial margin has to be looked at with a wide-angle lens. It’s not just block 59. The same way people in Amapá can pollute Guyana and Suriname, Pará can pollute Amapá,” says Luís Takiyama.

Two drilling licenses already denied

One confirmation that the socio-environmental vulnerability of this coastline isn’t limited to the Foz do Amazonas Basin is the fact that in December 2021 the environmental agency Ibama had already denied Petrobras a drilling license for blocks 3 and 5 of the Barreirinhas Basin, some 90 miles offshore.

At the time, the environmental agency ruled that the project submitted by Petrobras was “environmentally infeasible.” The technical report on which the denial was based said the impacts of a possible oil spill “are of great magnitude and in certain cases irreversible, making it impossible to establish a reliable timeframe for the recovery of ecosystems such as mangrove forests and endangered species such as Amazonian manatees and countless species of birds and chelonians.” The state-run oil firm appealed but the process is at a standstill.

Today, it’s as if the entire region were holding its breath, waiting to see how the saga of FZA-M-59 will end. During an auction in 2013, 45 blocks were awarded in the equatorial margin. But because environmental licensing is such a challenge, some companies have asked to suspend their contracts or have simply returned their areas, precisely what Shell did last year with four blocks in the Barreirinhas Basin. Right now, according to the Brazilian oil regulator ANP, 34 blocks have been awarded on this coastline. However, 16 of the contracts have been suspended.

Inside the government, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change is still negotiating publication of a presidential decree calling for a Sedimentary Area Environmental Assessment for the equatorial margin. This kind of study, which takes a broader look at a region’s compatibility with the oil industry, has to be ordered as a joint initiative with the Ministry of Mines and Energy, now headed by Alexandre Silveira, who, as the government’s most aggressive advocate of oil exploration, is putting up resistance to the idea.

In addition to making environmental licensing safer by avoiding the issuance of what Brazil’s environmental watchdog has called a “free pass to uncertainty,” the assessment would have the political effect of postponing any decision until after the 30th UN Climate Change Conference, or COP30, which will take place in Belém in 2025. Given that COP28, held in Dubai in late 2023, urged countries to “transition away from fossil fuels,” much pressure will likely be felt by oil producers, including the Brazilian hosts.

The mangroves of Oiapoque form an ecosystem that would need many years to recover if hit by oil. Photo: Enrico Marone/Greenpeace

Meanwhile, pressure to grant the license is likely to intensify following the change of command at Petrobras. Named to replace Jean Paul Prates, the new president, Magda Chambriard, was director of the oil regulator ANP when the blocks in the equatorial margin were auctioned off.

Sanderlings are one of the species that use Maracá-Jipioca as a shelter during migration. Photo: Marizilda Cruppe/Greenpeace

How to face a jaguar

Júlio, who is active in the national movement of artisanal fishers, is speaking out for many reasons. Like everyone in fishing communities on the Amazon coast, he is upset about predatory deep-sea industrial fishing. The use of large nets sacrifices small fish and disrupts spawning cycles.

Iranildo Coutinho, head of Maracá-Jipioca Ecological Station, says the problem also affects his unit. “Smaller fishers working in the region use 500- or 600-meter nets. The [industrial fishermen] who come from outside have 5-kilometer, 8-kilometer, nets. They cast the nets way out there, and then the nets circle back in, carried by the tide,” says Iranildo. “They create a barrier along the coast and capture schools that are coming to the island to spawn.”

Iranildo survived the administration of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro because nobody was interested in heading up a place that had no human residents. The ecological station encompasses wetlands and mangrove forests. The latter consist of red and black mangroves, trees whose roots and trunks have adapted to living in flooded and salt-water environments. In addition to swamp ghost crabs, typical of mangroves, these forests are home to spotted jaguars and tapirs, as well as throngs of birds such as scarlet ibises, great egrets, sanderlings, and black-bellied whistling ducks.

When our boat enters the rivers of Maracá-Jipioca, we hear the nonstop singing of birds. Jumping in the shallow waters are largescale four-eyes, so named because each eye is split into two lobes, with its own cornea and pupil, one adapted to see above water and the other below. This fish species, small and without much meat, inattentively enters the food chain of birds and other fish.

But what every outsider wants to catch a glimpse of here is a spotted jaguar, an estimated 60 of which live inside the station. Since the cats don’t usually let themselves be seen, researchers have to capture their images with trail cameras.

Suddenly, the big attraction of our trip becomes a jaguar paw print, spotted by Marivaldo on the banks of the Jacitara River. Perereca silences the outboard motor so the finding can be confirmed—and also so we won’t frighten the feline, just in case he or she is nearby and decides to make an appearance.

Even Perereca has only seen a jaguar twice in his 17 years at the park, once close up, near the headquarters, when he was angling for catfish. He advises us what to do if we ever find ourselves in a similar situation. The secret: Don’t run! Instead, turn toward the jaguar, look them in the face, and slowly walk backwards. Only at a safe distance can you turn around and walk away without fear.

Kind of like what’s happening with oil.

The 60 or so jaguars who live inside the station are rarely seen, but Elimarcos knows what to do if one makes an appearance. Photo: Girlan Dias/ICMBio

The journalist Claudia Antunes traveled to Amapá at the invitation of Greenpeace

Report and text: Claudia Antunes

Editing: Talita Bedinelli

Photo Editor: Lela Beltrão

Fact-checker: Plínio Lopes

Proofreader (Portuguese): Valquíria Della Pozza

Spanish translation: Meritxell Almarza

English translation: Diane Whitty

Infographics: Rodolfo Almeida

Copyediting and finishing: Natália Chagas

Editorial workflow coordination: Viviane Zandonadi

News editor: Malu Delgado

Editor-in-chief: Talita Bedinelli

Editorial director: Eliane Brum